You want koryu? Come to Japan –or not! A Worldwide Koryu Dojo Report Review

Text by Grigoris Miliaresis

Things to do in a pandemic

It started in the spring of 2020 as a reaction to Covid and the confining measures; yes, Japan didn’t have real lock-down policies like Europe or the US but pretty much all martial arts activities including demonstrations, seminars, tournaments and even regular practice, were suspended and that can really put a crimp in the workflow of a magazine that exists to cover exactly these activities. So when Takashi Ogawa, my associate editor for the last ten years heard that we could do a series on classical arts dojo and groups overseas, he immediately saw it for what it was: an opportunity to have some interesting content without needing to move around.

The truth is, though, that it didn’t start as a reaction to Covid: that was only the pretext. The initial impetus was a wish to review an article from 1996 titled “You want koryu? Come to Japan!” published in Stanley Pranin’s (1945-2017) “Aikido Journal” and written by Diane Skoss, managing editor of the magazine and founder of the publishing company Koryu Books and the website koryu.com Ms Skoss’ opinion mattered because at that time she had lived in Japan for ten years, had practiced various modern martial arts as well as Shinto Muso-ryu and Toda-ha Buko-ryu; also she was married to Meik Skoss, another long-term resident of Japan, member of the circle of the legendary martial artist, instructor and researcher Donn F. Draeger (1922-1982) and practitioner of Yagyu Shinkage-ryu, Toda-ha Buko-ryu, Shinto Muso-ryu and Tendo-ryu.

From #16, Shutokukan in New Jersey, USA (Meik and Diane Skoss, Tenshin Buko-ryu, Japanese Festival at the Missouri Botanical Gardens, 2012 [photo by Wes Foreman])

I read this article around the time it was published and was amazed. Not because it said things that I hadn’t already thought myself (being a journalist I knew the importance of research) but because it implied there was enough interest in koryu outside Japan to warrant the need for setting such criteria. Where? Certainly not in Greece and its neighboring countries so in the US? Who would be interested in them? Sure, I could understand why people would be interested in ninjutsu that had, not too long ago, become a worldwide phenomenon thanks, mostly, to Stephen K. Hayes’ work but koryu? With the 21st century just around the corner and UFC and the Gracie family already gaining ground in the international martial arts’ collective conscience? How did we get from Draeger and his small circle to the need for defining koryu for the world?

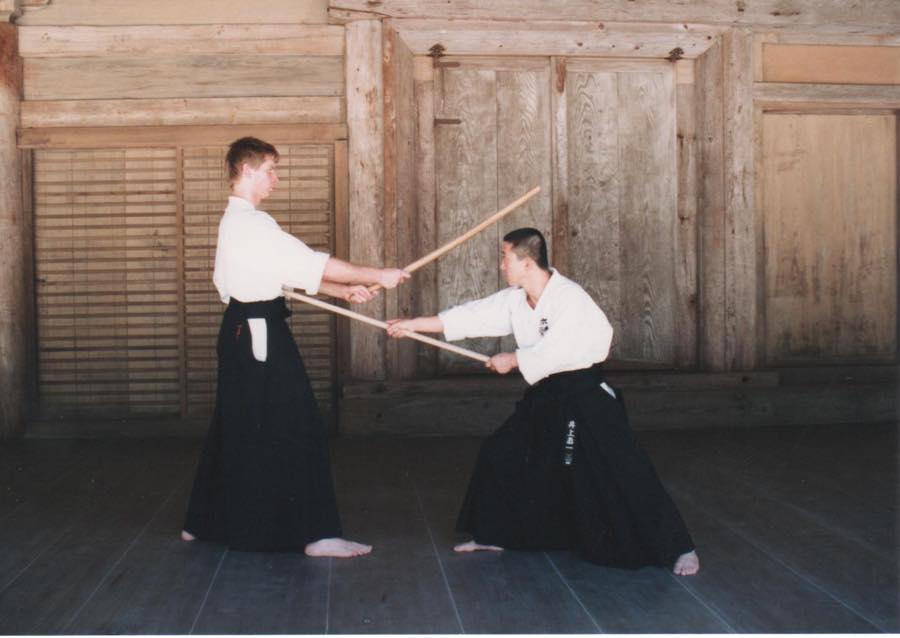

From #14, Mugendojo in Hawaii (Donn F. Draeger and Quintin Chambers)

The State of Koryu

The answer to that question is complicated and that would be the subject of my original article idea; since this isn’t that article, I’ll just summarize: Draeger’s work, the people in his circle who returned to their home countries and started groups and dojo, a growing interest in Japan, the proliferation of modern martial arts and fighting sports, globalization in general and Japan’s attempts in it as well as the snowballing expansion of the Internet all played their role in koryu becoming an option for martial artists, experienced and inexperienced alike. And since most of these things kept on growing and growing, in the 27 years that passed since the publication of Ms Skoss’ article, koryu followed along, becoming bigger and bigger outside Japan; as a matter of fact, and if all variables are taken into account, one could argue they are now bigger abroad than they are here.

From #29, Shoshin Kan Dojo, Finger Lakes Koryu-kai in Ithaca, New York, USA (jodoka from around the world attended “Gasshuku 2000,” sponsored by the International Jodo Federation (IJF). )

Koryu questions

Are they big enough to negate Ms Skoss’ premise that “if you want koryu you need to come to Japan”? That was the question I wanted to have answered with the series I pitched to my editor and I am sure that his curiosity about the outcome of such a research also fueled his decision to green-light the series. As for the technical part, that was easy: we would contact teachers and/or group leaders of koryu from around the world and would present them with a set of questions that had to be simple enough to allow them to describe their personal journeys in the world of classical arts, give a snapshot of the state of the arts in their dojo and countries and perhaps even express some of their ideas about them.

From #12, Melbourne Koryu Kenkyukai in Australia (Tatsumi-ryu practice)

These questions were: When and how did you get involved with the classical art(s) you practice? How widespread is the classical art(s) you practice in your country? How about classical arts in general? Do you and the members of your group travel to Japan to practice? What is the biggest difficulty in practicing classical Japanese martial arts? What is the difference between practicing classical and modern Japanese martial arts? What is your art(s)’ strongest characteristic, historically or technically? What is the benefit of practicing classical Japanese martial arts in the 21st century -especially for someone who isn’t Japanese? Is there a Japanese community in you city? Do you have any connections to them and to other aspects of Japanese culture? And added to them was a “Dojo ID” section where respondent would provide information such as the name, location and foundation year of their organization, affiliations, their name and credentials, number of members, members advanced/beginners ratio, days of practice/week and of course electronic contact information.

From #23, Redwood Kyudojo in California, USA (Redwood Kyudojo’s yamichi pathway with o-mato target)

The series went live on the October 2020 issue of “Hidden” and premiered with my old iaido/kendo dojo in Athens; the focus here was in it as a dojo of Muso Jikiden Eishin-ryu. And it kept going for two and a half years, until April 2023 featuring 30 dojo/groups from Europe, America, Asia and Australia. The arts we covered were Shinto Muso-ryu, Muso Jikiden Eishin-ryu, Hyoho Niten Ichi-ryu, Ono-ha Itto-ryu, Tendo-ryu, Tennen Rishin-ryu, Tenshinsho-den Katori Shinto-ryu, Araki-ryu, Ogasawara-ryu, Soshuishi-ryu, Yagyu Shinkage-ryu, Kashima Shinden Jikishinkage-ryu, Tenshin Buko-ryu, Takenouchi-ryu, Yagyu Shingan-ryu, Morishige-ryu, Tatsumi-ryu, Shinto Hatakage-ryu, Choken Batto Jutsu Kage-ryu, Daito-ryu Aikijujutsu (Kodokai) and Hontai Yoshin-ryu –in all, 21 arts, 16 armed and five unarmed (Takenouchi-ryu, Araki-ryu, Yagyu Shingan-ryu, Daito-ryu and Hontai Yoshin-ryu).

From #1, Furyu Dojo from Athens, Greece (Muso Jikiden Eishin-ryu Chuden #6, Iwanami)

Koryu answers

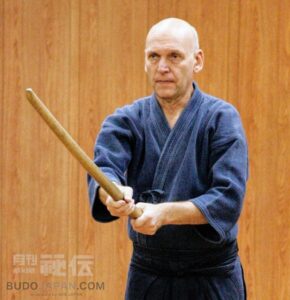

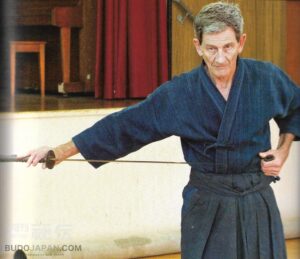

Going a little deeper into numbers, these 21 arts are taught by 38 instructors to 616 students; not an insignificant number (that’s about four times the number of people demonstrating in Tokyo’s major koryu events) but certainly not big enough to be considered of real consequence. Even if we assumed that it’s just a 10% of the real number, that would mean there are 380 instructors and 6160 students of koryu budo outside Japan; and our sample was not just some random 10%! As a matter of fact, among these 30 dojo some are run by living legends of the koryu budo community, people like Phil Relnick, Quintin Chambers, Pascal Krieger and David Hall who have devoted their life to the study and dissemination of Japan’s martial traditions for over 50 years. And as a matter of fact, this was another reason I wanted to do this series: to pay a small tribute to these people and their work that was the reason I, and hundreds of people like me, got interested in this arts.

Phil Relnick (From #10, Shintokan in Seattle)

Quintin Chambers (From #14, Mugendojo in Hawaii)

Pascal Krieger (From #13, Shung-Do-Kwan Budo in Geneva, Switzerland)

David Hall (From #4, Hobyokan dojo from Maryland, United States)

There is, however, a chance that these 30 dojo/groups give a limited picture and this has to do with the popularity of two schools, namely Tenshinsho-den Katori Shinto-ryu and Shinto Muso-ryu. Among the 30, we got only two teaching the former and 10 teaching the latter; while 10 out of 30 gives a good idea of Shinto Muso-ryu’s popularity, two out 30 does not do justice to the growth of Tenshinsho-den Katori Shinto-ryu’s four active lines. And even the 10 Shinto Muso-ryu dojo might be a little misleading because thanks to All-Japan Kendo Federation’s jodo which works as an introduction to Shinto Muso-ryu, there are certainly many more dojo of that art all over the world than the 10 we recorded. Going back to the total number of koryu dojo, I would feel confident to say that our sample represents 1/3 of the koryu dojo all over the world i.e. that there are about 100 overall –yes, it’s speculation but I would call it “informed”!

From #18, Tai itsu kan (泰一館) in Madrid, Spain (Shinto Muso-ryu Jojutsu training)

From #10, Shintokan (神稲館) in Seattle (Katori Shinto-ryu Naginata)

Culture matters

It isn’t a numbers’ game, though. What was much more fascinating for me where the qualitative elements of this small research. The fact, for example, that out of the 38 instructors, only two have not even traveled to Japan: most of the remaining 36 not only travel frequently but have spent considerable time here, ranging from five years to 30. And even though some of them do not take lessons anymore, because their teachers have passed or because they have full certifications that allow them to be completely independent, they keep on returning to visit their teachers (or pay respects to their teachers’ graves), to meet the (Japanese) students in their teachers’ dojo (which used to be their dojo when they were living in Japan) and to bring their own students from overseas so they can practice with the Japanese. This shows a deep connection to Japan and a connection that the people concerned, teachers and students alike, want to preserve because they consider important for the study of these arts.

From #6, Seifukan Dojo in Hawaii (Choufukan, Bitchuden Takenouchi-ryu, Shiraha dori. [Photo by Ono Yotaro])

From #24, Aiki-Kobudo-Kai Leer e.V. (Ulf Rott and Sugino Yoshio Tenshin Shoden Katori Shinto-ryu Training)

Still, all these teachers and their students endure, and persevere, and spread their arts: the reason the two of our respondents never came to Japan and some others have only come once or twice, was that they were themselves students of fully licensed non-Japanese –in other words they are second-generation, non-Japanese licensed instructors. And while they want to eventually practice here and they still appreciate the cultural aspect, they don’t need to because they already learned the arts in their home countries. Which means that it took less than 30 years for Ms Skoss’ premise about needing to come to Japan for koryu to have lost at least some of its initial weight. Thanks to some open-minded Japanese teachers and to some truly dedicated non-Japanese students, these traditions can now be taught and learned outside Japan but through building ties that in the end make Japan even stronger.

From #26, Athens Araki-ryu dojo in Greece (Araki-ryu Sankyoku no Dan)

People and their stories

The narration of these dedicated students’ personal journey in the world of classical martial arts is, I believe, one of the most fascinating aspects of this series; it certainly is one of the most educational. Spread over half a century, from the 1950s to the 2010s (the most recent among them, Mr. Anton Kossarenko from Kazakstan decided to move from modern to classical martial arts just 5 years ago, in 2018.) these journeys might have been sparked by a variety of reasons that ranges from pure chance to very deliberate choice but they all have something in common: all of these people considered -and still consider- the classical arts something worth devoting their life to and spreading to more people in their home countries.

From #11, Tennen Rishin-ryu Bujutsu Hozonkai, Almaty Keikokai, Keisokan Dojo in Kazakhstan

Spread all over the classical arts are the almost mythical (and often literally mythical) stories of their founders, stories involving trips all over the land (and sometimes to unknown, fairy-tale lands), encounters with amazingly skilled masters, exhausting practice, insights that come through states almost metaphysical in nature and deep changes that lead to Buddha-like realization. But even a glance at the lives of the instructors in our series, even in the extremely abbreviated version we included in their profiles, is enough to show that these stories still happen today because they happened to these people; Japan isn’t an unknown fairy-tale land (but you could argue it was for them when they first landed here from all over the world) and as for the masters, the practice, the insights and the deep changes, they are certainly all there!

From #20, Hontai Yoshin-ryu Belgian branch (enbu in Japan)

Epilogue –and a roll call

I always enjoy my work but especially this project has been particularly fulfilling and I hope I will be able to repeat it: as I wrote above, there are at least another 70 dojo that we haven’t introduced yet and I would love to give them the space to share their stories. I have had the opportunity to talk to some amazing people, including some who were paramount in developing my own understanding of koryu budo (including the inspiration for this series, Ms Skoss herself), read their insights, interpretations and ideas and see images of them and their students practicing in all kinds of spaces and settings but wearing the same clothes and wielding the same weapons. And while one reason that I wanted to do this project was to give to these people some of the recognition they deserve, another was to remind to the Japanese classical arts community, our community, that it is bigger than it thinks –for better or for worse.

From #3, Sosuishi-ryu Kumiuchi Koshi No Mawari Seirenkan Eikoku Keikokai, London, UK

Finally, because this series wouldn’t have existed without these exceptional individuals’ willingness to talk to us, more often than not reluctantly because they felt what they do is not worth getting exposure (which is of course a testimony to their character!) it is only fitting to end this (hopefully first part of the) Worldwide Koryu Dojo Report with a mention of their names. In order of appearance they are Spyros G. Drossoulakis, Valentino Guzzinati, Steve Delaney, David Hall, Bill Fettes, Wayne Muromoto, Marcos Sala, Colin Hyakutake Watkin, Philip Hinshelwood, Phil Relnick, Will Schutt, Kevin Lam, Anton Kossarenko, Liam Keeley, Pascal Krieger, Quintin Chambers, Per Eriksson, Meik Skoss, Diane Skoss, Taneli Takala, Jussi Jussila, Vicente Borondo, Jed Konopka, Guy Buyens, Alain Berckmans, Frederic Roncioni, Brian Hanlon, Joe Cheslic, Ulf Rott, Maria Peterson, Tim Macmillan, Roland Gericke, Peter Boylan, Thanassis Mpantios, Harvey King, Raymond Sosnowski, Larry E. Bieri and Nathan Scott.

From #1: Ono-ha Itto-ryu dojo from Ferrara, Italy (seminar with Reigakudo teachers -this time, Hideyuki Kaiwa and Toru Ishizaki sensei.)

Grigoris Miliaresis

About the writer

Grigoris Miliaresis has been practicing Japanese martial arts since 1986. He has dan grades in judo, aikido and iaido and has translated in Greek over 30 martial arts’ books including Jigoro Kano’s “Kodokan Judo”, Yagyu Munenori’s “The Life-Giving Sword”, Miyamoto Musashi’s “Book of Five Rings”, Takuan Shoho’s “The Unfettered Mind” and Donn Draeger’s “Martial Arts and Ways of Japan” trilogy. Since 2007 his practice has been exclusively in classic schools: Tenshin Buko-ryu Heiho under Ellis Amdur in Greece and Kent Sorensen in Japan and, since 2016, Ono-ha Itto-ryu under 17th headmaster Sasamori Takemi and 18th headmaster Yabuki Yuji.

http://about.me/grigorismiliaresis