[Monthly column] Worldwide Koryu Dojo Report Vol.6 Hawaii Martial Arts Club—Seifukan Dojo

Interview and Text by Grigoris Miliaresis

Wayne Muromoto and Clark Watanabe demonstrating Bitchuden Takenouchi-ryu kogusoku at the Missouri Botanical Gardens Japan Festival.

The first issue of Furyu, 1994

The sixth part of “Monthly Worldwide Koryu Dojo Report!” gets to know a little more about Wayne Muromoto, an ethnic Japanese American from Hawaii, teacher of Bitchuden Takenouchi-ryu and Urasenke sado practitioner. Muromoto sensei was well-known in the English-speaking koryu community for being the publisher and editor of “Furyu” magazine (1994-2000), the first serious attempt for a magazine dedicated to these arts.

Wayne Muromoto and George Miller practicing in Manoa District Park as indoor gatherings for five or more people is currently prohibited due to Covid-19 measures. Photo by Dave Hee.

Name: Hawaii Martial Arts Club-Seifukan Dojo

Location: Honolulu, Hawaii

Foundation year: 1985

Arts practiced: Bitchuden Takenouchi-ryu and informally (without formal association) Muso Jikiden Eishin-ryu

Local affiliation: None

Japan affiliation (instructor/organization): Ono Yotaro, 16th headmaster of Bitchuden Takenouchi-ryu

Instructor’s name: Wayne Muromoto

Instructor’s credentials/grades: Toritate Shihan

Number of members: about seven practicing regularly

Members advanced/beginners ratio: Two shoden mokuroku (shodan), plus long distance: one shoden mokuroku (nidan), one chuuden mokuroku (sandan).

Days of practice/week: Currently Sunday mornings (used to also be Wednesday nights before Covid-19)

Website/social media/email: email: wmuromoto@hotmail.com. Facebook: Martial Arts Club of Hawaii: https://www.facebook.com/groups/558007651048788

1) When and how did you get involved with the classical art(s) you practice?

The entrance to Choufukan, Wayne Muromoto’s home dojo in Kyoto.

When I came to Japan in 1984, on a scholarship to study chanoyu at the Urasenke Foundation in Kyoto, a friend introduced me to Ono Yotaro sensei and the Choufukan. I was immediately taken by the style and by sensei’s character as an artist and bugeisha.

Group shot after a training session at Choufukan, circa 1990s. Front row left: Graham Pluck, South America. Third from left: Alex Kask, Vancouver, Canada. Middle: Wayne Muromoto. Second from right Anna Seabourne, Menkyo Kaiden Shihan, United Kingdom. Standing, middle: Ono Yotaro Shinjin, kancho of Choufukan.

Wayne Muromoto’s student Joe Fichter receiving Shoden Mokuroku from Ono Yotaro kancho, Kyoto, circa 1990s.

I also trained at the Butokuden under Ohmori Masao sensei, Muso Jikiden Eishin-ryu and ZNKR iaido. Under his ongoing tutelage, I received ZNKR ranking but when he passed away, my connections to the group were severed by his successors. I currently have an informal relationship with my sempai, Ken Maneker, who teaches in Vancouver, Canada; Ken studied under Ohmori sensei and under the late Iwata sensei and his Muso Jikiden Eishin-ryu is very much influenced by them and his own research into the ryu’s more “koryu” aspects. I do not rank my students or hold any official affiliation with any other group other than Maneker sensei currently in Muso Jikiden Eishin-ryu.

2) How widespread is the classical art(s) you practice in your country? How about classical arts in general?

In America, there are several koryu groups but in terms of numbers, we are not collectively as big as modern budo or MMA, etc. For Bitchuden Takenouchi-ryu, we have a group in Vancouver, Canada, and in Mexico and study groups in the Midwest and South America.

A group shot in November 2020 during the Covid Pandemic.

3) Do you and the members of your group travel to Japan to practice?

I try to go back to Kyoto at least once a year, and sometimes we have visitors from Japan to Hawaii; this year, our plans were canceled because of Covid-19.

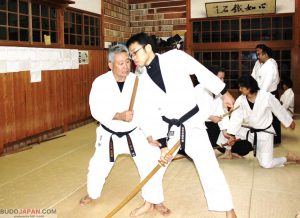

At Choufukan, circa 2018 Photo by Ono Yotaro.

Dinner after training, 2019. From Left: Ono Yotaro sensei, Wayne Muromoto and Clark Watanabe, chuuden mokuroku. Clark is also bishop of the Hawaii Shingon-shu.

4)What is the biggest difficulty in practicing classical Japanese martial arts?

Offering prayers to Atago Daimyojin before an annual Ryusosai embu, Choufukan, Kyoto, Japan. Circa 1990s.

I think first, not many people are really interested in it, even in Hawaii. Then many people may seem interested but they do not understand the difference in attitude, culture and training style, so they soon drop out. Therefore getting new members seem to be a problem.

5) What is the difference between practicing classical and modern Japanese martial arts?

Most classical training methods are kata-geiko, and the goals are mainly to perfect one’s techniques, mental attitude, and study the history and culture. In many modern systems, competition and attaining rank seem to be the goals to the detriment of other goals. This is a very broad generalization, of course. I am friends with some wonderful karate, judo and aikido teachers who also believe in perfecting techniques and a student’s spirit as the main goals, but they are often considered “mavericks” by their peers. My students are now middle-aged and older, so they are seeing the advantages to kata geiko because they can continue to train without straining their bodies too much and getting injured.

Clark Watanabe (left) and Joe Fichter practice kusarigama in the park, 2019.

Bitchuden Takenouchi-ryu bojutsu practice at Honolulu Myohoji Mission in Honolulu, Hawaii. Left: Miles Sakai, right: Albert Cloutier. Photo by Dave Hee

6) What is your art(s)’ strongest characteristic, historically or technically?

I would say perhaps the emphasis on close-quarter combat. The school specializes in the kogusoku, a short sword. The other technical characteristic, in terms of learning goals, is that it stresses being able to improvise and handle any situation. As a sogo bujutsu, there are over 400-odd kata in the style using different weapons, armed and unarmed. The idea is that once you master some basic concepts and movements, you can adapt them to all sorts of weapons and situations so that you are not “frozen” or unable to counter an attack.

Wayne Muromoto and Clark Watanabe demonstrating Bitchuden Takenouchi-ryu kenjutsu at the Missouri Botanical Gardens Japan Festival.

Wayne Muromoto and Clark Watanabe demonstrating Bitchuden Takenouchi-ryu jutte jutsu at the Missouri Botanical Gardens Japan Festival.

Historically, we are told that when the founder, Takenouchi Hisamori, was visited by a mystical yamabushi, he was taught that “where you stand is where the battle is decided,” i.e. one must meet conflict and end it as soon as possible. The yamabushi also broke Hisamori’s very long bokuto in half and instructed him in the advantages of using a shorter weapon. The other technical doctrine, I believe, is that whenever possible, one should avoid conflict, but if it is necessary to engage, to try to avoid bloodshed. That is why Hisamori was also taught hojojutsu, tying up and holding an enemy captive without killing him. Only if that is not possible should you cause harm, and then lastly slay an attacker.

Wayne Muromoto and Clark Watanabe demonstrating Bitchuden Takenouchi-ryu kusarigama jutsu at the Missouri Botanical Gardens Japan Festival.

7) What is the benefit of practicing classical Japanese martial arts in the 21st century -especially for someone who isn’t Japanese?

There are several benefits, which may not be relevant to many people seeking “martial arts.” 1. It is a way to understand traditional Japanese culture. Many times, I have discussions with my students that start with a koryu bugei concept but I must explain it in terms of traditional Japanese culture, especially from what I learned from studying chanoyu. 2. Second, there is of course the health aspect. Coming to practice helps to keep you physically and mentally healthy. 3. Third is the martial aspect. As I tell my students, learning how to use a sword in armor is not really relevant in this day and age, but the concepts of distancing, timing, rhythm, and awareness (zanshin), still helps you in daily life, social interactions, and possibly avoiding physical confrontations. And you never know; something you learn may help you in an unusual situation. I had a former student who, after training very hard with me for several years, entered the US military. He was a language specialist in Chinese but served as an intelligence officer in Afghanistan for three tours of duty. He said the mental concepts he learned from koryu actually helped him in some unusual situations.

George Miller (left) and Hamed Dehnavi practice Bitchuden Takenouchi-ryu naginata jutsu. 2020.

8) Is there a Japanese community in you city? Do you have any connections to them and to other aspects of Japanese culture?

The main temple (Hondo) of Myohoji, Honolulu. Seifukan Dojo practices at a multipurpose building next to the hondo (main building).

Hawaii has a very large Nikkei community. The first Japanese immigrants came to Hawaii in 1868, Meiji Gannen, and they are called the Gannen Mono and until the 1920s, many more came to work in the pineapple and sugar plantations. My grandparents came from Niigata and Okinawa in the 1910s. Currently ethnic Japanese make up about 23% of the population (185,502 in the 2010 Hawaii State Census). There are many biracial people who are Japanese-something and are often called “hapa” (half-and-half) in Pidgin English; people who identify as Japanese plus other races are 312,292. (Hawaii’s total population is 1,360,301)

I am ethnically Japanese. Besides teaching koryu budo, I am also a student of the Urasenke School of Tea in Hawaii and was the Tankokai Urasenke Hawaii Association’s chief operations officer for ten years before stepping down in 2017; I currently serve on its board of advisors. I am kept busy with teaching koryu, learning tea, and of course working as a computer graphics and photography instructor at a college.

Choufukan, Bitchuden Takenouchi-ryu, Shiraha dori. Photo by Ono Yotaro.