[Monthly column] Worldwide Koryu Dojo Report Vol.7 Spain Muso Jikiden Eishin-ryu iaijutsu

Interview and Text by Grigoris Miliaresis

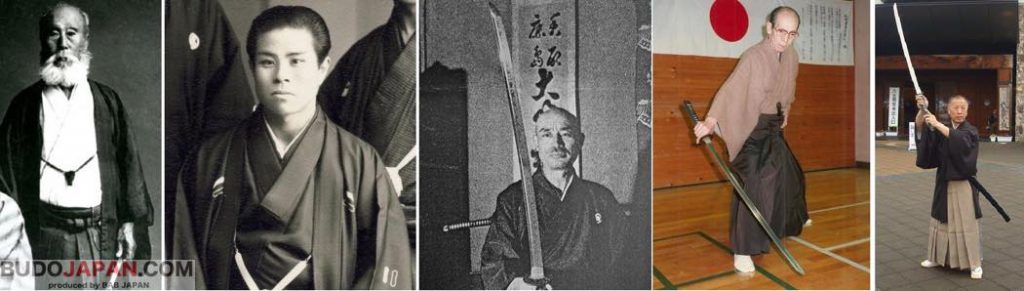

This is the seventh part of our tour of the world’s koryu dojo and we return to Europe and to the Spain branch of Muso Jikiden Eishin-ryu Yamauchi-ha run by Art History PhD Marcos A. Sala Ivars. Dr. Ivars has a unique perspective for classical martial arts having specialized as an academic in researching Japanese weapons and the history of art linked to samurai and Japan’s Imperial House.

Name: Spain Muso Jikiden Eishin-ryu iaijutsu

Name: Spain Muso Jikiden Eishin-ryu iaijutsu

Location: Madrid

Foundation year: 2011

Arts practiced: Muso Jikiden Eishin-ryu iaijutsu

Local affiliation: None

Japan affiliation (instructor/organization): 21st generation head Sekiguchi Takaaki/Komei. Nihon Kobudo Kyokai, Komei Jyuku, Nippon Koden Bujutsu

Instructor’s name: Marcos Sala/Sekiguchi Kenryu

Instructor’s credentials/grades: Monjin, head of Spanish branch, teaching license (menkyo), adopted by the current head of the Tokyo Yamauchi line Number of members: 15 students (4 monjin)

Members advanced/beginners ratio: 4/11

Days of practice/week: 2 days, 2 hours per day.

Website/social media/email: salaivars@hotmail.com,

https://www.facebook.com/Spain-Mus%C3%B4-Jikiden-Eishin-Ry%C3%BB-iaijutsu-Komei-Juku-651903441586413/

1) When and how did you get involved with the classical art(s) you practice?

Because of my Japanese art and history academical background, I wanted to study historical Japanese martial arts. After reaching 3rd dan in ZNKR iaido and attending seminars in several koryu, I met Sekiguchi Komei, 21st generation head of Muso Jikiden Eishin-ryu iaijutsu (Yamauchi-ha Tokyo) in a 2009 seminar in Rennes, France led by local branch head, Jaff Raji. After only 10 days of practice I realized I found the koryu I was searching for a long time and was accepted to become monjin and devote the rest of my life practicing it. For some years I’ve also practiced Shinto Muso-ryu jojutsu, Kashima Shinden Jikishinkage-ryu kenjutsu, and Ryoen-ryu.

Because of my Japanese art and history academical background, I wanted to study historical Japanese martial arts. After reaching 3rd dan in ZNKR iaido and attending seminars in several koryu, I met Sekiguchi Komei, 21st generation head of Muso Jikiden Eishin-ryu iaijutsu (Yamauchi-ha Tokyo) in a 2009 seminar in Rennes, France led by local branch head, Jaff Raji. After only 10 days of practice I realized I found the koryu I was searching for a long time and was accepted to become monjin and devote the rest of my life practicing it. For some years I’ve also practiced Shinto Muso-ryu jojutsu, Kashima Shinden Jikishinkage-ryu kenjutsu, and Ryoen-ryu.

2)How widespread is the classical art(s) you practice in your country? How about classical arts in general?

In our country we’re lucky to have MJER’s three main lines in different regions. At the time, I represent and teach my line at the honbu dojo in Madrid; besides us there are also in Spain dojo of Shinto Muso-ryu, Tenshinsho-den Katori Shinto-ryu, Suio-ryu, Tatsumi-ryu, Asayama Ichiden-ryu, Toda-ha Buko-ryu, Shinto Muso-ryu and Shindo Yoshin-ryu and several dojo of gendai koryu (schools based in koryu bujutsu and founded by menkyo kaiden in them but created post-1868); one such school I also represent and teach is Ryoen-ryu naginatajutsu.

3) Do you and the members of your group travel to Japan to practice?

I travel once a year to train with Sekiguchi sensei and other sensei of my ryu (once a year I also bring him to Spain to teach); sometimes monjin students too travel to Japan to train. Every time I go to Japan, I also train under other shihan from other dojo; the Yamauchi-ha Tokyo/Komei Jyuku is mainly located in Kanto (Tokyo, Saitama and Chiba) but has one more dojo in Okayama. Once-twice a year, I travel to other countries as well, holding seminars with Sekiguchi sensei: we have official dojo in Spain, France, Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Czech Rep. Slovakia, Slovenia, Poland, Hungary, Bulgaria, Russia, Indonesia, South Korea, New Zealand, Australia, USA, Cuba, Argentina and Chile.

I travel once a year to train with Sekiguchi sensei and other sensei of my ryu (once a year I also bring him to Spain to teach); sometimes monjin students too travel to Japan to train. Every time I go to Japan, I also train under other shihan from other dojo; the Yamauchi-ha Tokyo/Komei Jyuku is mainly located in Kanto (Tokyo, Saitama and Chiba) but has one more dojo in Okayama. Once-twice a year, I travel to other countries as well, holding seminars with Sekiguchi sensei: we have official dojo in Spain, France, Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Czech Rep. Slovakia, Slovenia, Poland, Hungary, Bulgaria, Russia, Indonesia, South Korea, New Zealand, Australia, USA, Cuba, Argentina and Chile.

4) What is the biggest difficulty in practicing classical Japanese martial arts?

I think that the biggest difficulty for foreigners and Japanese alike, is the same as studying any other classical art like sado, kado or nogaku: being part of a traditional culture with old, strict rules you cannot break. It’s not just about learning Japanese culture, but also an old or traditional Japanese way of life, so sometimes even Japanese people don’t want be involved in such strict, traditional worlds. Also, you must understand you’re not doing something that can be “improved” or changed: your duty is only to pass the information you received as pure as you can to the next generation. As humans, all we want to create something and leave our footprint for eternity, but if you want to practice koryu bujutsu you must forget this and I think for many people that could be very difficult.

I think that the biggest difficulty for foreigners and Japanese alike, is the same as studying any other classical art like sado, kado or nogaku: being part of a traditional culture with old, strict rules you cannot break. It’s not just about learning Japanese culture, but also an old or traditional Japanese way of life, so sometimes even Japanese people don’t want be involved in such strict, traditional worlds. Also, you must understand you’re not doing something that can be “improved” or changed: your duty is only to pass the information you received as pure as you can to the next generation. As humans, all we want to create something and leave our footprint for eternity, but if you want to practice koryu bujutsu you must forget this and I think for many people that could be very difficult.

5) What is the difference between practicing classical and modern Japanese martial arts?

Modern arts’ constant pursuit for medals/trophies and gradings; this also contributes to putting a contemporary aesthetic of the forms over historical knowledge. In my experience with judo and karate and especially with ZNKR iaido, I saw how the waza were changed on one year and come back to the original on the next, with no rationale beyond aesthetics and financial gain or how people change their swords and waza to be more “spectacular” or win a competition. As for grading, it’s case by case, but I often see that after nidan, importance on the technical level is 20% and the remaining 80% is politics; I’m not saying this doesn’t happen in koryu, but I think the ratio is much lower. In koryu, or at least in my school, the most important thing is understanding the waza’s meaning, so, even if you can’t do it correctly, you can pass the knowledge to next generation. When our body allows us to do it correctly we must push our limits and improve control of distance, power, speed and timing.

Modern arts’ constant pursuit for medals/trophies and gradings; this also contributes to putting a contemporary aesthetic of the forms over historical knowledge. In my experience with judo and karate and especially with ZNKR iaido, I saw how the waza were changed on one year and come back to the original on the next, with no rationale beyond aesthetics and financial gain or how people change their swords and waza to be more “spectacular” or win a competition. As for grading, it’s case by case, but I often see that after nidan, importance on the technical level is 20% and the remaining 80% is politics; I’m not saying this doesn’t happen in koryu, but I think the ratio is much lower. In koryu, or at least in my school, the most important thing is understanding the waza’s meaning, so, even if you can’t do it correctly, you can pass the knowledge to next generation. When our body allows us to do it correctly we must push our limits and improve control of distance, power, speed and timing.

6) What is your art(s)’ strongest characteristic, historically or technically?

As Sekiguchi Komei said in an interview, MJER is not a battlefield school but a school dealing with sudden attacks and surviving very complicated situations, not a school for long fights but for resolving any problem with one or few cuts; therefore it teaches proper cutting regardless of the situation. In its iai/batto, every time we draw the sword and return it to the scabbard, we do it with the edge facing up. No matter the cut’s angle, if it’s one- or two-handed or if it’s a thrust, we never reveal what we’re thinking by moving the sword’s edge sideways. Our line is the last MJER practicing with long swords. The school’s core was created for sudden attacks indoors or outdoors with a very long katana (3 shaku 1 sun/1m/3’). In the Edo period the blade’s length changed many times and in the early 19th century, long swords came again in fashion, especially in the southern domains. The Yamauchi-ha standardized a 3 shaku (91cm/2’9”) blade also allowing for personalized adjustments and the three previous heads used both long and standard swords but the current head believes we must always use the long sword to push ourselves. Because of this length but also for strategic reasons inside each kata, we wear the sword with the tsuka on the body’s far right side, with the tsuba almost at the right hipbone level.

As Sekiguchi Komei said in an interview, MJER is not a battlefield school but a school dealing with sudden attacks and surviving very complicated situations, not a school for long fights but for resolving any problem with one or few cuts; therefore it teaches proper cutting regardless of the situation. In its iai/batto, every time we draw the sword and return it to the scabbard, we do it with the edge facing up. No matter the cut’s angle, if it’s one- or two-handed or if it’s a thrust, we never reveal what we’re thinking by moving the sword’s edge sideways. Our line is the last MJER practicing with long swords. The school’s core was created for sudden attacks indoors or outdoors with a very long katana (3 shaku 1 sun/1m/3’). In the Edo period the blade’s length changed many times and in the early 19th century, long swords came again in fashion, especially in the southern domains. The Yamauchi-ha standardized a 3 shaku (91cm/2’9”) blade also allowing for personalized adjustments and the three previous heads used both long and standard swords but the current head believes we must always use the long sword to push ourselves. Because of this length but also for strategic reasons inside each kata, we wear the sword with the tsuka on the body’s far right side, with the tsuba almost at the right hipbone level.

7) What is the benefit of practicing classical Japanese martial arts in the 21st century -especially for someone who isn’t Japanese?

Being part of old Japan’s history and culture and contributing to the continuation of this heritage -like being the librarian of Alexandria’s Library! And of course, all the other mental and physical benefits present in any martial arts’ or sports’ practice.

8) Is there a Japanese community in you city? Do you have any connections to them and to other aspects of Japanese culture?

There are Japanese communities in Madrid and other Spanish cities and I have a strong connection with them, as well with the Japanese Embassy and Japan Foundation where I sometimes lecture or demonstrate. My wife is Japanese so every time I go to Japan I get involved in cultural or traditional events with her family and also, because of my PhD I have relationships with Japanese sword fittings’ artists. My field of academic research is Japanese art history linked to the samurai and the Imperial House and it made me open multiple research channels and study Japanese culture from different aspects, looking through the lense of many centuries and learning both from famous people of the past and present day, living artists.

There are Japanese communities in Madrid and other Spanish cities and I have a strong connection with them, as well with the Japanese Embassy and Japan Foundation where I sometimes lecture or demonstrate. My wife is Japanese so every time I go to Japan I get involved in cultural or traditional events with her family and also, because of my PhD I have relationships with Japanese sword fittings’ artists. My field of academic research is Japanese art history linked to the samurai and the Imperial House and it made me open multiple research channels and study Japanese culture from different aspects, looking through the lense of many centuries and learning both from famous people of the past and present day, living artists.