text and photo by Grigoris Miliaresis

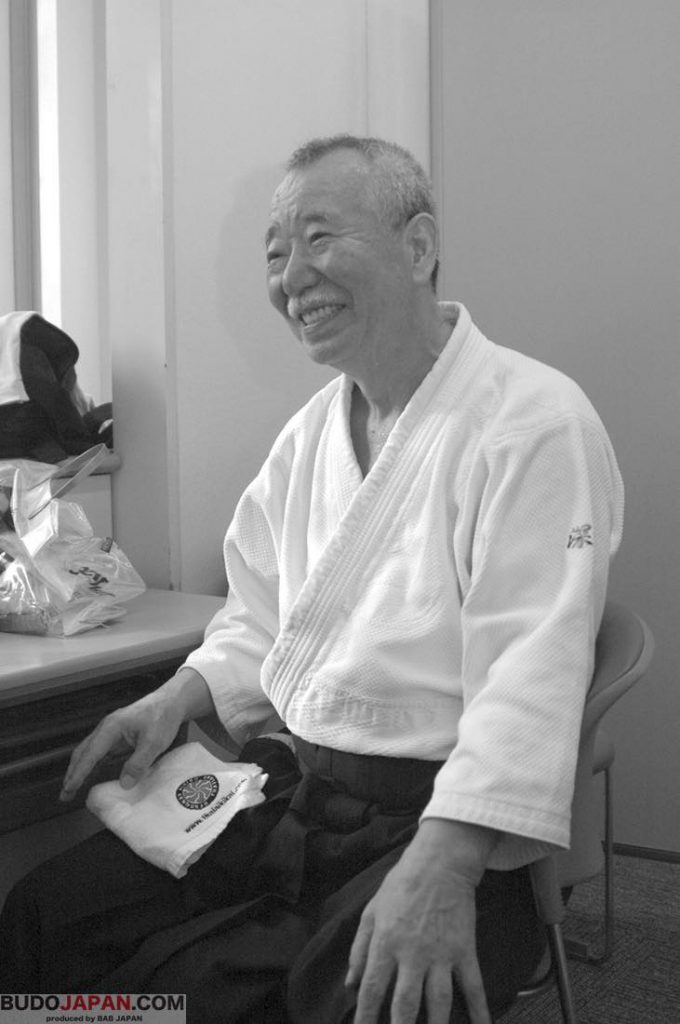

The father of aikido in Thailand

It is true so I have to admit it: even though I have trained in aikido for almost a decade, even though I have participated in seminars with some of the highest level teachers the art has to offer, even though a big part of my professional life has been writing about martial arts and even though for the last few years I have been living in Japan, I hadn’t heard of Fukakusa Motohiro before I took the assignment for this article. And I have to also admit that going to the National Olympic Memorial Youth Center in Yoyogi that day I was a little worried about what I was going to see; besides seeing Fukakusa sensei’s class from up close (i.e. on the tatami) we were also going to interview him. That for the coverage of this particular event “Hiden’s” editor-in-chief the knowledgeable Mr. Shiozawa was to join my colleague, Mr. Ogawa and me made me wonder even more. Who was this man?

It is true so I have to admit it: even though I have trained in aikido for almost a decade, even though I have participated in seminars with some of the highest level teachers the art has to offer, even though a big part of my professional life has been writing about martial arts and even though for the last few years I have been living in Japan, I hadn’t heard of Fukakusa Motohiro before I took the assignment for this article. And I have to also admit that going to the National Olympic Memorial Youth Center in Yoyogi that day I was a little worried about what I was going to see; besides seeing Fukakusa sensei’s class from up close (i.e. on the tatami) we were also going to interview him. That for the coverage of this particular event “Hiden’s” editor-in-chief the knowledgeable Mr. Shiozawa was to join my colleague, Mr. Ogawa and me made me wonder even more. Who was this man?

Doing the necessary preparation before going to the event I started getting some glimpses of why this man is important. Very important. Having started aikido in the early 1960s, when the Aikikai was still under the guidance of the art’s founder, Ueshiba Morihei and with many of the greats still teaching and training there, he was chosen to carry out a very difficult task: to disseminate the art to Thailand, a country with a martial art of its own (i.e. Muay Thai) very well rooted to its natives’ consciousness. And to do that with only three years of training aikido and a second dan as credentials! Of course those three years were spent in the presence of giants and the second dan was signed and handed by Ueshiba Morihei himself but still I can’t even contemplate the magnitude and the difficulty of the task.

And he did it! Going through a variety of difficulties, he managed to establish aikido not only in Thailand (which is still he base and which, after fifty years he has every reason to call his “home”) but in the greatest Southeast Asia. And since 2008, to give this network he created an institutional base: the Aikido of South-East Asian Nations Fellowship (ASEANF) which besides Thailand also includes dojo from Cambodia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, and Vietnam; this organization was part of a dream the man Fukakusa sensei considers his teacher and the man who sent him to Thailand in the first place: late Tamura Nobuyoshi shihan, 8th dan Aikikai (1933-2010).

Through Fukakusa sensei’s hard work, and through networking between Japan and Thailand (in which the Aikikai played a significant role), his first team of aikidoka managed to move from the College of Physical Education (at the National Stadium of Bangkok) to their own dojo, the Renbukan and from there to create a strong cluster of six dojo all over the country. What is more important was that even in a country with such a long and strong tradition in a martial art very different from aikido, Fukakusa sensei managed to make aikido appear interesting to the eyes of police and army officers and to demonstrate the art to the King of Thailand; this happened in 1982, in the opening of the Thai-Japan Youth Center in Din Daen.

Through Fukakusa sensei’s hard work, and through networking between Japan and Thailand (in which the Aikikai played a significant role), his first team of aikidoka managed to move from the College of Physical Education (at the National Stadium of Bangkok) to their own dojo, the Renbukan and from there to create a strong cluster of six dojo all over the country. What is more important was that even in a country with such a long and strong tradition in a martial art very different from aikido, Fukakusa sensei managed to make aikido appear interesting to the eyes of police and army officers and to demonstrate the art to the King of Thailand; this happened in 1982, in the opening of the Thai-Japan Youth Center in Din Daen.

Today Fukakusa Motohiro (or Khun Somchai as is known among the Thai) sensei holds the 8th dan from the Aikikai; a fair compensation for his 50 years of hard work in Thailand and the broader area. Furthermore he travels extensively and teaching seminars not only in his sphere of influence, so to speak, but as far as Ukraine, France, Romania, Hungary, and Israel. All this while still retaining his posts as Chairman of ASEANF, President of Aikido Association of Thailand and of course teacher to his own dojo, the Renbukan. Most web sites label him “the father of aikido in Thailand” –and judging from his accomplishments, this is probably an understatement!

The rapid moves of a good kendoka at his peak

The above were enough for me to understand why this man is indeed important for aikido and the Aikikai. Now the question was what about his presence on the tatami? After all, astonishing as a person’s achievements might be in the so called “politics”, this is a martial art and the only real test is the one that one takes (and hopefully passes!) every time they step on the tatami. I know this might sound somehow inappropriate for an aikido practitioner who has not only been training for 50 years but who is also an 8th dan holder but I have been in the martial arts long enough myself and I have seen enough practitioners (teachers and students) of various arts not living up to their ranks to know better than be impressed just by a title, however high this title be.

The above were enough for me to understand why this man is indeed important for aikido and the Aikikai. Now the question was what about his presence on the tatami? After all, astonishing as a person’s achievements might be in the so called “politics”, this is a martial art and the only real test is the one that one takes (and hopefully passes!) every time they step on the tatami. I know this might sound somehow inappropriate for an aikido practitioner who has not only been training for 50 years but who is also an 8th dan holder but I have been in the martial arts long enough myself and I have seen enough practitioners (teachers and students) of various arts not living up to their ranks to know better than be impressed just by a title, however high this title be.

As soon as the warm up (the standard warm up seeing in Aikikai dojo all over the world) was over and the actual teaching began though, all the doubts I might had vanished. This man was the real deal –he seemed to own the tatami (not an easy feat, considering there where at least 400 people up there) and he could grab and hold the interest of even the most skeptical practitioner. Always with a smiling face he would wander around the training pairs and offer his insights by allowing everyone a hands-on experience on what he meant during his teaching; and whenever he saw that a student couldn’t (or wouldn’t) understand his point he would repeat the technique again and again playfully, revoking images of Ueshiba Morihei at his best.

Fukakusa sensei’s aikido was not “spectacular”; it was basic aikido as seen from the Doshu or many other teachers. But it was strong, it was self-assured and well-balanced and it contained everything that characterizes good aikido. Going through the basic aikido techniques (ikkyo, kote gaeshi, irimi nage, kokyu nage etc.) he demonstrated all the basic elements: impeccable tai sabaki, perfect timing, good kuzushi and stability while in motion –all that regardless of the size or the level of his partner. I can’t tell with certainty how many seminar participants he trained with in the one hour his class lasted but I didn’t see him lacking these qualities at any moment.

One thing that really impressed me in Fukakusa Motohiro’s aikido (and one that took me completely by surprise, at that) was his speed, especially when demonstrating atemi, the various strikes that are part of any good aikido technique. Even though he is in an admirably good condition, especially considering his age (he is 70 years old) his punches were as fast as would be expected from someone less than half his age: he reminded me the rapid moves of a good kendoka at his peak or, more appropriate maybe, of a good young boxer. I am not sure if this is the case, but I am guessing this might have to do with the fact that for many years he has had to prove his aikido to people very well versed with one of the most relentless boxing styles known to man –again, I am talking about the Thai boxers that (as he told as in his interview later) were invariably among his students.

Relaxation, awareness of openings and natural stance

My colleagues in “Hiden” asked me what I would single out as the three main elements of Fukakusa sensei’s class. And this would be hard since, from an aikidoka’s standpoint (and I do still consider myself enough of an aikidoka to say this!) there must have been at least a dozen important insights in the one hour his class lasted. If I was forced to pick the three more important though, I would say (I) relaxation, (II) awareness of openings and (III) natural stance; rethinking of his class as I write this, I feel that everything he did and taught that day in Yoyogi included those elements and was supported by them. Furthermore, I believe he himself considered those three very important because he emphasized them whenever he had the chance, both in his teaching and when he trained with individual seminar participants.

Relaxation is a funny thing: almost all aikido teachers preach it but very often what passes for relaxation is actually limpness: an almost dead condition lacking muscular tone and depriving the aikidoka of all choices. Fukakusa sensei also emphasized it, sometimes comically illustrating the stiff shoulders many have while performing aikido, but what was most important that he demonstrated it in his movement while executing any technique. His relaxation was anything but limp: it had all the nerve needed to control his partner and perform the technique he wanted but also the softness necessary to change his body position according to the partner’s reaction; in other words, he was able to dominate the whole situation in the most natural way.

Relaxation is a funny thing: almost all aikido teachers preach it but very often what passes for relaxation is actually limpness: an almost dead condition lacking muscular tone and depriving the aikidoka of all choices. Fukakusa sensei also emphasized it, sometimes comically illustrating the stiff shoulders many have while performing aikido, but what was most important that he demonstrated it in his movement while executing any technique. His relaxation was anything but limp: it had all the nerve needed to control his partner and perform the technique he wanted but also the softness necessary to change his body position according to the partner’s reaction; in other words, he was able to dominate the whole situation in the most natural way.

His demonstration of how to be aware of openings is something that, again, I will attribute to the interaction he must have had with people who have practiced Thai boxing. Every time he picked a partner, he would point out their openings with one of the extremely fast atemi I mentioned before, underlining something that is sometimes missing in aikido: the sense that this is a martial art and that the partner is supposed to be an opponent who will exploit any opening. Without preaching disharmony and lack of cooperation, Fukakusa sensei stressed more than enough that a technique that starts (or continues) with openings is a technique lacking awareness and, consequently, that the result will be weak and prone to failure. I really hope all the participants remember this important lesson; if they did I’m certain their aikido will be much better.

His demonstration of how to be aware of openings is something that, again, I will attribute to the interaction he must have had with people who have practiced Thai boxing. Every time he picked a partner, he would point out their openings with one of the extremely fast atemi I mentioned before, underlining something that is sometimes missing in aikido: the sense that this is a martial art and that the partner is supposed to be an opponent who will exploit any opening. Without preaching disharmony and lack of cooperation, Fukakusa sensei stressed more than enough that a technique that starts (or continues) with openings is a technique lacking awareness and, consequently, that the result will be weak and prone to failure. I really hope all the participants remember this important lesson; if they did I’m certain their aikido will be much better.

The third point, the one about natural stance is also a controversial matter in aikido circles: many aikido instructors seem to worship the hanmi no kamae and among them there is a big majority that overdoes the positioning of the feet in a way that would seem unnatural to most exponents of other martial arts (a well-known American aikido teacher I know, calls that “aiki feet”!) I don’t know if Fukakusa sensei’s background in judo (he practiced judo since he was 11 years old and continued until the time he went to college and found out aikido) is responsible for his… standpoint but in his teaching independence from a fixed stance was one of the main motifs; the point he made quite a few times was that adherence to a particular stance limits the options and can result to a stiff body and mind and to inability to adjust to the demands of the confrontation.

The third point, the one about natural stance is also a controversial matter in aikido circles: many aikido instructors seem to worship the hanmi no kamae and among them there is a big majority that overdoes the positioning of the feet in a way that would seem unnatural to most exponents of other martial arts (a well-known American aikido teacher I know, calls that “aiki feet”!) I don’t know if Fukakusa sensei’s background in judo (he practiced judo since he was 11 years old and continued until the time he went to college and found out aikido) is responsible for his… standpoint but in his teaching independence from a fixed stance was one of the main motifs; the point he made quite a few times was that adherence to a particular stance limits the options and can result to a stiff body and mind and to inability to adjust to the demands of the confrontation.

These are the technical points. But there is a point I would also like to make and one that seems to me of equal importance: Fukakusa sensei’s comportment during his class. Especially for someone putting so much emphasis in practical aspects of aikido, his attitude was so playful and joyful that made training seem like a game among friends –and it accomplished that without missing the critical aspect of the real and the martial. For me, this might have been the most important teaching of all and one that I believe managed to get through to seminar participants in the most direct way: through feeling the atmosphere sensei created during the one hour his class lasted.

The East: still a mystery

As I finish this small account of Fukakusa Motohiro’s class, I realize once again how inadequate words are to express a physical discipline like the martial arts and even more so, the way this discipline is illustrated by an exponent who has been training, teaching and refining his art for 50 years. I also realize how people (both in the West but, I suspect, also in Japan) are limited by their own perspective: I know for a fact that there are thousands of aikidoka in Europe and the United States who, like me, have never heard of Fukakusa sensei even though they know very well other teachers with much less experience than him. And it is sad that in this day and age, when communication technology has managed to bring everything to our TVs and our computer screens, the East remains for many people a mystery. Even in the world of martial arts, where the people involved have a particular interest for the countries that gave birth to the arts, gems like Fukakusa Motohiro haven’t found the recognition they rightfully deserve from the entirety of the people involved. And it is a shame because their teaching, their insights and their whole course through life contain vital lessons for all of us.

As I finish this small account of Fukakusa Motohiro’s class, I realize once again how inadequate words are to express a physical discipline like the martial arts and even more so, the way this discipline is illustrated by an exponent who has been training, teaching and refining his art for 50 years. I also realize how people (both in the West but, I suspect, also in Japan) are limited by their own perspective: I know for a fact that there are thousands of aikidoka in Europe and the United States who, like me, have never heard of Fukakusa sensei even though they know very well other teachers with much less experience than him. And it is sad that in this day and age, when communication technology has managed to bring everything to our TVs and our computer screens, the East remains for many people a mystery. Even in the world of martial arts, where the people involved have a particular interest for the countries that gave birth to the arts, gems like Fukakusa Motohiro haven’t found the recognition they rightfully deserve from the entirety of the people involved. And it is a shame because their teaching, their insights and their whole course through life contain vital lessons for all of us.

Related article:International Aikido Federation’s 11th International Aikido Congress: Christian Tissier’s class

About the author

About the author

Grigoris Miliaresis has been practicing Japanese martial arts since 1986. He has dan grades in judo, aikido and iaido and has translated in Greek over 30 martial arts’ books including Jigoro Kano’s “Kodokan Judo”, Yagyu Munenori’s “The Life-Giving Sword”, Miyamoto Musashi’s “Book of Five Rings”, Takuan Shoho’s “The Unfettered Mind” and Donn Draeger’s “Martial Arts and Ways of Japan” trilogy. Since 2007 his practice has been exclusively in classic schools: Tenshin Buko-ryu Heiho under Ellis Amdur in Greece and Kent Sorensen in Japan and, since 2016, Ono-ha Itto-ryu under 17th headmaster Sasamori Takemi and 18th headmaster Yabuki Yuji.

http://about.me/grigorismiliaresis