text and photo by Grigoris Miliaresis

A charming man

“Is there something you would like me to ask sensei Tissier?” I asked my Japanese colleague from “Hiden” while we were drinking coffee (or, in my case, tea) before we entered the sports hall of the National Olympic Memorial Youth Center for the French shihan’s seminar; the reason being that I was supposed to be the one talking with him after the seminar was over (not that there was any need of course because Christian Tissier’s Japanese is fine –but we’ll come to that later). His reply was: “I would like to know why he is so popular”, a question that makes perfect sense but which a Japanese probably wouldn’t easily ask for fear of not being considered impolite. Apparently me not being Japanese made things fine!

It is a legitimate question: even in Japan, where top grade aikido teachers are in abundance, there are few Western names that carry a certain weight –and Christian Tissier’s is certainly among them. And even if someone doesn’t know that, a look at the International Aikido Federation’s 11th Aikido Congress and Seminar list of names for the seminar will reveal it: out of the 20 classes being offered that week with names literally starting and ending with “Ueshiba” (waka sensei Ueshiba Mitsuteru and Third Doshu Ueshiba Moriteru respectively) and including some of the best the Honbu Dojo and the Japanese Aikikai world has to offer, there were only two non-Japanese: Australian Tony Smibert and Christian Tissier.

It is a legitimate question: even in Japan, where top grade aikido teachers are in abundance, there are few Western names that carry a certain weight –and Christian Tissier’s is certainly among them. And even if someone doesn’t know that, a look at the International Aikido Federation’s 11th Aikido Congress and Seminar list of names for the seminar will reveal it: out of the 20 classes being offered that week with names literally starting and ending with “Ueshiba” (waka sensei Ueshiba Mitsuteru and Third Doshu Ueshiba Moriteru respectively) and including some of the best the Honbu Dojo and the Japanese Aikikai world has to offer, there were only two non-Japanese: Australian Tony Smibert and Christian Tissier.

Even though having being born with two years separating them, having started aikido at almost the same time, having attained the rank of the 7th dan and the title of shihan and having achieved similar goals (basically one could say that what Tissier sensei accomplished in France, Smibert sensei accomplished in Australia, following the legacy of his teacher, late 8th dan shihan Sugano Seiichi) even people who don’t know Smibert sensei do at least know of Tissier. What makes this even more spectacular is that especially for Japan, his base (Paris, France) is very far –and I don’t mean only in kilometers! Still, his reputation is well established even here and judging from what we saw on the tatami before, during and after his class, the seminar made it even stronger.

Even though having being born with two years separating them, having started aikido at almost the same time, having attained the rank of the 7th dan and the title of shihan and having achieved similar goals (basically one could say that what Tissier sensei accomplished in France, Smibert sensei accomplished in Australia, following the legacy of his teacher, late 8th dan shihan Sugano Seiichi) even people who don’t know Smibert sensei do at least know of Tissier. What makes this even more spectacular is that especially for Japan, his base (Paris, France) is very far –and I don’t mean only in kilometers! Still, his reputation is well established even here and judging from what we saw on the tatami before, during and after his class, the seminar made it even stronger.

Christian Tissier’s journey on the path of aikido started very early when he was only 11 years old –first with compatriot Jean-Claude Tavernier and then with Nakazono Mutsuro (1918-1994) a unique and multi-faceted teacher and student of Ueshiba Morihei who went to France in 1961, only one year before young Tissier decided to take up the art that would prove to be the field where he would shine. By 1968 and at the very young age of 17 he was already a 2nd dan and with a very strong desire to come to Japan, something that he managed to do just one year later. For someone with so big a passion for aikido the travel to Japan was inevitable as was the fact that only six months weren’t going to satisfy him; the year would be 1976, when he decided to return to France then holder of the 4th dan in his art.

The years of Christian Tissier in Japan have been well documented: his relationship with Yamaguchi Seigo, Saotome Mitsugi and Osawa Kisaburo, all legends of the Aikikai and above all with the second Doshu, Ueshiba Kishomaru as well as his incessant thirst for more aikido that made him improvise to extend his stay in Japan (among other things working as a model and as a teacher of the French language). And outside aikido, his studying of the Japanese language Sophia University, his training in kickboxing at the famous Meijiro Gym with Shima Mitsuo and Fujiwara Toshio and his experimenting with various other martial arts, among which Kashima Shin Ryu with Inaba Minoru.

The years of Christian Tissier in Japan have been well documented: his relationship with Yamaguchi Seigo, Saotome Mitsugi and Osawa Kisaburo, all legends of the Aikikai and above all with the second Doshu, Ueshiba Kishomaru as well as his incessant thirst for more aikido that made him improvise to extend his stay in Japan (among other things working as a model and as a teacher of the French language). And outside aikido, his studying of the Japanese language Sophia University, his training in kickboxing at the famous Meijiro Gym with Shima Mitsuo and Fujiwara Toshio and his experimenting with various other martial arts, among which Kashima Shin Ryu with Inaba Minoru.

Equally well documented –at least in Europe- is his return to France, his opening of the dojo “Le Cercle Christian Tissier” one of the biggest dojo in the continent, his contribution in the creation of the Fédération Française Aïkido, Aïkibudo et Affinitaires (FFAAA) or French Federation of Aikido, Aikibudo and Affiliated Arts, one of the two great bodies governing aikido in France which numbers over 35,000 members, his constant travelling for seminars, his books, his superb demonstrations of the art in France, his promotion to 5th, 6th and 7th dan (in 1981, 1986 and 1998 respectively, the latter personally handed to him by Ueshiba Kisshomaru himself) up to his commendation from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan this past July for his contribution to the dissemination of aikido in his country.

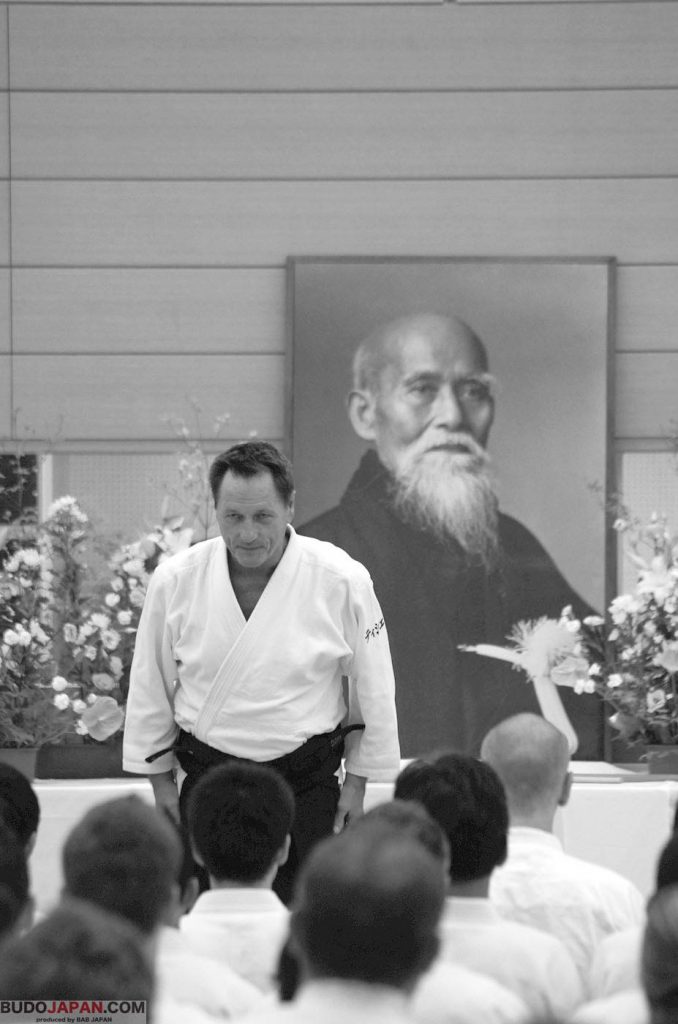

Incredible as it might seem, all these accomplishments seem to disappear when someone has the opportunity to actually meet Christian Tissier, either on the tatami or outside because any thoughts about his history gets lost in the shadow of his charm; I know it is an unusual word to use when talking about a martial arts teacher but since the first time I saw him (I was fortunate enough to having attended one of his seminars in Greece) this was the main thing that came to my mind: this man is charming. He is not dominating but he has a strange way of making you feel drawn to him both when executing an aikido technique and when talking to him. And in my opinion this comes from being always relaxed and at complete ease; needless to say this is what makes his aikido extraordinary as well.

“Cancel”, “equalize”and “limit”

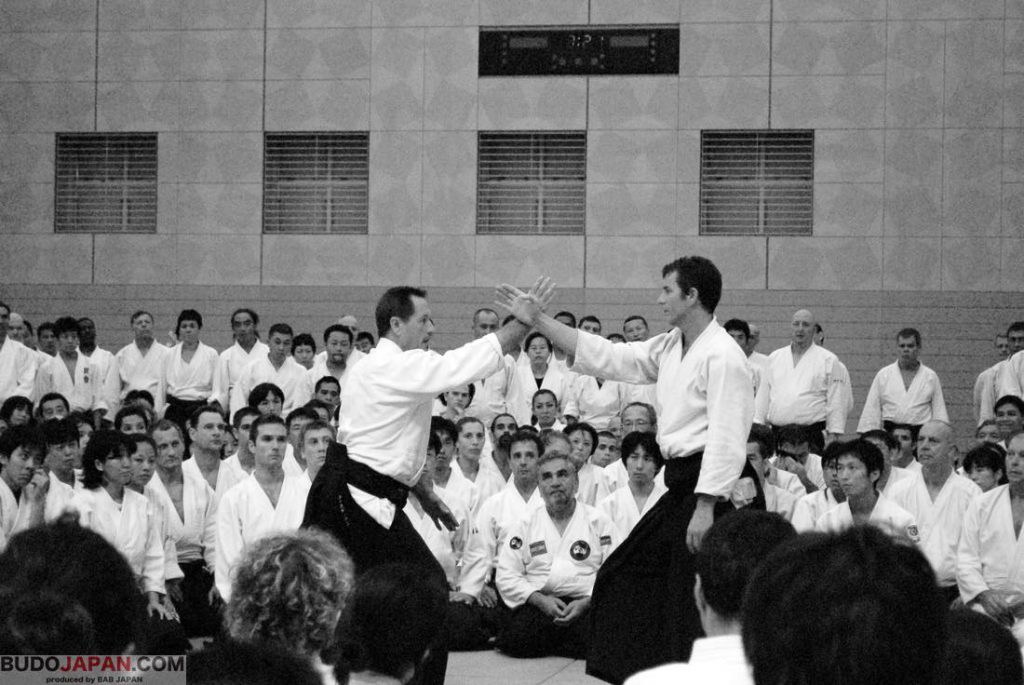

The one hour he had in his disposal was one of the best aikido classes I have seen and at the same time one of the most entertaining; it was almost as if watching a top class actor performing and combining a set script with adlibbed parts according to what his partners where doing each time. Often laughing and joking but always serious and in impeccable control of the situation he explained principles and not techniques, something rather unusual in the aikido world where most teachers tend to go for the latter, and particularly the basics, especially when they have to deal with a class so big and so diverse (in Tissier sensei’s class there were about 600 people attending and as in all classes of the event the crowd included everyone –from beginners to some of the highest level instructors from all over the world).

The one hour he had in his disposal was one of the best aikido classes I have seen and at the same time one of the most entertaining; it was almost as if watching a top class actor performing and combining a set script with adlibbed parts according to what his partners where doing each time. Often laughing and joking but always serious and in impeccable control of the situation he explained principles and not techniques, something rather unusual in the aikido world where most teachers tend to go for the latter, and particularly the basics, especially when they have to deal with a class so big and so diverse (in Tissier sensei’s class there were about 600 people attending and as in all classes of the event the crowd included everyone –from beginners to some of the highest level instructors from all over the world).

Still, this is a trend among Western teachers, particularly the most experienced ones (and they rarely get more experienced than Tissier who is being doing this thing for 50 years!): finding the common ground of aikido techniques and using Ueshiba Morihei’s thinking as a starting point, they come up with the guiding “rules” behind the techniques and by teaching that they allow students apply these rules to all the possibilities that might occur on the mat. Of course the basic techniques are always there and Tissier sensei was quick to point that out in our conversation after the seminar: “We all work on the same techniques”, he pointed out “but eventually, as we evolve and become better at this, we create our own aikido much in the way musicians become creative after having repeated their basic material like scales over and over again. The basics are the same but with time each practitioner’s aikido will be different and this diversity is one of the strong points of aikido”.

Still, this is a trend among Western teachers, particularly the most experienced ones (and they rarely get more experienced than Tissier who is being doing this thing for 50 years!): finding the common ground of aikido techniques and using Ueshiba Morihei’s thinking as a starting point, they come up with the guiding “rules” behind the techniques and by teaching that they allow students apply these rules to all the possibilities that might occur on the mat. Of course the basic techniques are always there and Tissier sensei was quick to point that out in our conversation after the seminar: “We all work on the same techniques”, he pointed out “but eventually, as we evolve and become better at this, we create our own aikido much in the way musicians become creative after having repeated their basic material like scales over and over again. The basics are the same but with time each practitioner’s aikido will be different and this diversity is one of the strong points of aikido”.

Asked about which points he would underline in his teaching that day, Tissier sensei summarized his class in three words: “cancel”, “equalize” and “limit”, all referring not only to the way tori would receive uke’s attack but to the way both tori and uke should act during the execution of the technique; this by itself is an interesting notion because most aikido teachers tend to differentiate between the two roles (hence the names “tori” and “uke”). For Tissier, both parts should be constantly aware of the situation and if they would detect an opening, they would try to cancel, equalize or limit each other’s actions thus creating more realistic and, in the end more honest and strong techniques. Demonstrating these concepts while teaching was particularly interesting and it was obvious that many seminar attendees hadn’t thought of aikido this way, “trapped” so to speak to the idea that when “A attacks this way, B should act that way”.

Asked about which points he would underline in his teaching that day, Tissier sensei summarized his class in three words: “cancel”, “equalize” and “limit”, all referring not only to the way tori would receive uke’s attack but to the way both tori and uke should act during the execution of the technique; this by itself is an interesting notion because most aikido teachers tend to differentiate between the two roles (hence the names “tori” and “uke”). For Tissier, both parts should be constantly aware of the situation and if they would detect an opening, they would try to cancel, equalize or limit each other’s actions thus creating more realistic and, in the end more honest and strong techniques. Demonstrating these concepts while teaching was particularly interesting and it was obvious that many seminar attendees hadn’t thought of aikido this way, “trapped” so to speak to the idea that when “A attacks this way, B should act that way”.

Ranks and their true meaning

This constant awareness is probably what allows Tissier sensei emit this aura of complete ease I mentioned above; on the other hand this isn’t something gained on the tatami alone –it has to be complemented by work done on a personal level outside (but in parallel to) the martial art. And talking with Christian Tissier later it became obvious that this is someone who has worked extensively with himself and has created a well-rounded and soundly structured thought. For example, when we mentioned some of his accomplishments (his ranks, the recent commendation from the Japanese MOFA etc.) we didn’t notice even the slightest smugness in his reaction: “I was surprised with that” he said “But I think it is important –not for me but for everybody practicing aikido, especially outside Japan. You know, when I started doing aikido, I had never thought that there would be a day that I would get a black belt, then a second dan, then a third etc. –the idea that there would come a time when foreigners could become 6th and 7th dan shihan was outside even the sphere of fantasy!”

“The true meaning and importance of ranks was first brought home to me by my first teacher and then by the second Doshu, Ueshiba Kisshomaru”, he continued “when I got my 2nd dan and later when I got my 6th and my 7th, they both reminded me that this was important because grades are accompanied by responsibilities –when a person graded in aikido acts, people perceive these actions as representing the world of aikido itself; in essence when you act, aikido acts! And while when I got my 2nd dan I was too young to understand that, with time it became obvious”. This sense of responsibility was prevalent in his reply to our question about what he believes is (or could be) a main problem in aikido; for Christian Tissier is “bad people” especially for those being on the teacher’s side: “People can get carried away by the authority and the power that accompanies the role of the teacher and their personal accomplishments in the art”, he said “And even though one’s accomplishments might be worthwhile, they still have to respect the student’s personality. The power plays and the abuse of the teacher’s position is one of the things that might harm aikido and we must be constantly aware of these situations”.

“The true meaning and importance of ranks was first brought home to me by my first teacher and then by the second Doshu, Ueshiba Kisshomaru”, he continued “when I got my 2nd dan and later when I got my 6th and my 7th, they both reminded me that this was important because grades are accompanied by responsibilities –when a person graded in aikido acts, people perceive these actions as representing the world of aikido itself; in essence when you act, aikido acts! And while when I got my 2nd dan I was too young to understand that, with time it became obvious”. This sense of responsibility was prevalent in his reply to our question about what he believes is (or could be) a main problem in aikido; for Christian Tissier is “bad people” especially for those being on the teacher’s side: “People can get carried away by the authority and the power that accompanies the role of the teacher and their personal accomplishments in the art”, he said “And even though one’s accomplishments might be worthwhile, they still have to respect the student’s personality. The power plays and the abuse of the teacher’s position is one of the things that might harm aikido and we must be constantly aware of these situations”.

As our conversation was coming to its close, I remembered my colleague’s question: “Why do you think you are so popular?” was the last thing I asked Tissier sensei understanding very well that for someone with his character this question would probably sound impolite. Still, without missing a beat he came up with probably the best answer I can think of: “Well, you understand this isn’t something I can say for myself”, he said smiling “And this is true for all people –we are liked by some and disliked by others. But yes, judging from the reception I get when I travel and teach I might indeed be well receive. Maybe because I make people dream: I took up a discipline 50 years ago, I never stopped working on it and this work allowed me to create something and to receive some recognition for what I created. So people know that it is possible after all!”

We greeted sensei and the people from the Aikikai who helped us do our job, exited the National Olympic Memorial Youth Center, ended up in a small café near the Sangubashi station and while drinking coffee (or, in my case, tea) I asked my colleague if he got his answer about Christian Tissier –he just smiled and nodded.

Related article:International Aikido Federation’s 11th International Aikido Congress: Fukakusa Motohiro’ class

About the author

About the author

Grigoris Miliaresis has been practicing Japanese martial arts since 1986. He has dan grades in judo, aikido and iaido and has translated in Greek over 30 martial arts’ books including Jigoro Kano’s “Kodokan Judo”, Yagyu Munenori’s “The Life-Giving Sword”, Miyamoto Musashi’s “Book of Five Rings”, Takuan Shoho’s “The Unfettered Mind” and Donn Draeger’s “Martial Arts and Ways of Japan” trilogy. Since 2007 his practice has been exclusively in classic schools: Tenshin Buko-ryu Heiho under Ellis Amdur in Greece and Kent Sorensen in Japan and, since 2016, Ono-ha Itto-ryu under 17th headmaster Sasamori Takemi and 18th headmaster Yabuki Yuji.

http://about.me/grigorismiliaresis