An Interview with Manaka Unsui, Founder of the Jissen Kobudo Jinenkan

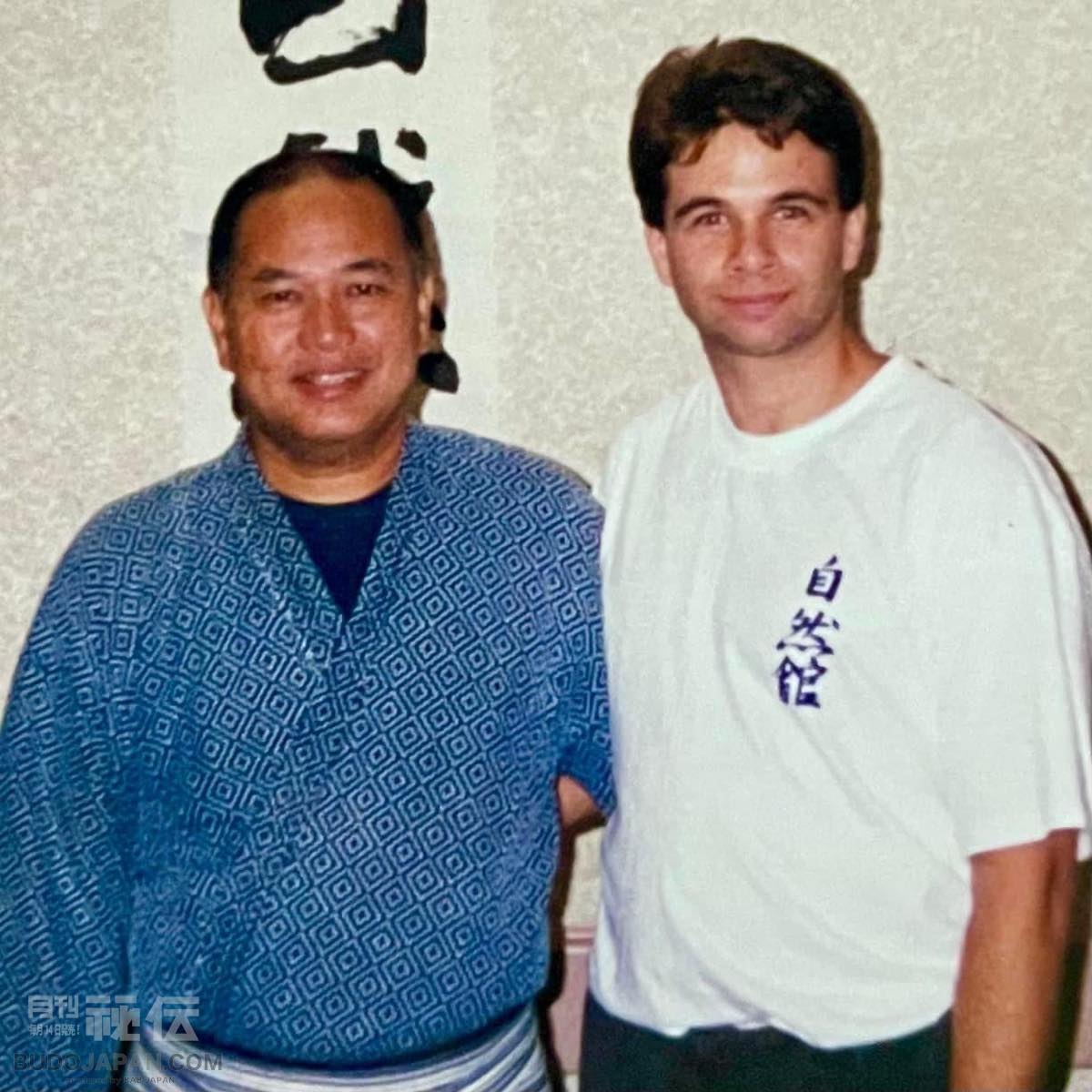

Left:Robert R. Gray Right:Manaka Unsui

In this interview, I speak with Manaka Unsui, founder of the Jissen Kobudo Jinenkan. As he enters his retirement, I thought it would be a good time to look back at his long career and the contributions he has made to kobudo—the traditional martial arts of Japan.

My first experience training with Manaka Sensei was at a seminar in Atlanta in 1999. In 2001, I moved to Japan to further my study in martial arts and meditation. Over the next 20 plus years, I continued to train under him, attaining the rank of 5th-dan and receiving a full Jinen-ryu menkyo kaiden license in 2022. I have also translated two books that he wrote: Kakusei-Mushin and The End of Anxiety.

Among the many things he has taught me, the concept of mushin or kakusei-mushin has been the most meaningful. It is something I try to focus on not only during my training but in my daily life as well. We discuss his research into this topic in the interview. Writing this article had a strange, full-circle feeling to it as I have now reached the age Manaka Sensei was when he founded the Jinenkan.

Robert R. Gray

1) How did you get started in martial arts?

Unsui: I first started out in judo when I was in the 6th grade and I continued into junior high school. Then I began practicing kendo as well and was doing them both during my second year of junior high. At that time, I entered a judo tournament in the area and I won first place. There was a martial arts teacher at the event from the Bujinkan dojo named Hatsumi Sensei. He asked where I was from and I told him I was from Noda. He said he was from Noda too and invited me to visit his dojo. The chairman of the convention happened to be sitting there and told me that Hatsumi Sensei was a ninjutsu teacher. I said, “Ninjutsu?” I was 14 years old and interested in that sort of thing, so I went to see him right away. That was 63 years ago.

Unsui: I first started out in judo when I was in the 6th grade and I continued into junior high school. Then I began practicing kendo as well and was doing them both during my second year of junior high. At that time, I entered a judo tournament in the area and I won first place. There was a martial arts teacher at the event from the Bujinkan dojo named Hatsumi Sensei. He asked where I was from and I told him I was from Noda. He said he was from Noda too and invited me to visit his dojo. The chairman of the convention happened to be sitting there and told me that Hatsumi Sensei was a ninjutsu teacher. I said, “Ninjutsu?” I was 14 years old and interested in that sort of thing, so I went to see him right away. That was 63 years ago.

Later, I taught in the Japan Self-Defense Forces, and sometimes I would teach martial arts in other countries. After I retired from the Self-Defense Forces, I moved to Baltimore, in America, and I taught there for three years. Once the skill level of the dojo-chos reached a certain point, I moved back to Japan.

2) I see, so you started in the Bujinkan. How is that different from what you teach now?

Unsui: The Bujinkan, hmmm. I don’t know. You’ve met Hatsumi Sensei before, right? Nobody knows what he’s talking about. That’s his style. People don’t even know what he is saying. He goes this way and that way. His way of doing martial arts was the same, going here and there. That’s his personality.

3) The times that I met Hatsumi Sensei, he didn’t seem to distinguish much between the various schools and their styles of movement.

Unsui: Exactly, and that was a big problem. We are a part of those schools’ histories and we are at risk of losing the traditional forms that have been handed down from generation to generation. If those forms are lost, we fail in our responsibility to the next generation. Our predecessors put their lives and blood on the line to create those techniques. It’s unfortunate not to preserve them. That is why I left the Bujinkan.

4) How would you summarize your own teaching methods?

Unsui: I’m a big believer in teaching according to the scrolls. That’s the most important thing when starting. First, learn the traditional movements. When the opponent changes, the technique will change accordingly, but the foundation remains the same. Without a strong foundation, the technique collapses. That’s the way you have to think in order to build a strong foundation.

Shinden-Fudo-ryu UDEORI 1

Shinden-Fudo-ryu UDEORI 2

Shinden-Fudo-ryu UDEORI 3

I teach about 700 techniques. That means 700 kihon, or basics. It is important to learn them properly. We will be doing this in today’s training as well. We’ll do one original technique, then variations, and after that, I’ll teach what I have devised—the keiko-no-ho—based on the other postures or kamae. So, for example, the basic technique might begin from a posture called seigan-no-kamae. What I’ve created are ways of doing the same technique from the other kamae such as hira-ichimonji, jumonji and so on. Each posture has a different mindset associated with it. So when doing the basic technique from a different kamae, the movement will change according to the feeling of the kamae. But the basic technique remains the same. If you can do this, then you can understand the true essence of the kamae and the true way to move. You’ll see the deeper reasoning behind the kamae. This is my way of adapting the technique to the environment.

When I trained with Hatsumi Sensei, I watched all of his movements and learned them first in my head. But he always did them differently, so when I practiced by myself, repeating the movements in front of a mirror, I wondered which of the ways I should practice. That’s when I decided to practice according to the scrolls.

5) When you taught in Baltimore, had you already started the Jinenkan?

Unsui: Yes, that’s right. I left the Bujinkan when I was 50 years old and started the Jinenkan shortly after. My way of thinking was very different from Hatsumi Sensei’s. Also my way of teaching was very different. This wasn’t good for either of us, and it would cause the students to get confused. Even if we were teaching the same technique, Hatsumi Sensei taught it one way, and I taught it another. I can’t really say which of our ways is better but I teach according to the scrolls, the way the techniques were written hundreds of years ago. Hatsumi Sensei taught by changing the technique every time according to the situation. That’s why our two styles didn’t match.

Manaka Kancho and Gray, the year 1999

6) Do you teach both unarmed and weapon techniques in the Jinenkan?

Unsui: Yes, I teach both weapons and unarmed techniques. The Jinen ryu school I created is all weapons, mainly short weapons including knife, jutte, and kusari-fundo. We also have sword. With the sword we have nito-jutsu (using two swords together) and regular sword. But the basic body movements or taijutsu comes from the other schools including Gyokko ryu, Koto ryu, Shinden Fudo ryu and so on. You should learn proper taijutsu first. When you learn using a weapon first, if that weapon gets taken away, you’ll forget the taijutsu. It’s all about how you move your feet, your body. I think I’m starting to understand this but sometimes I feel like I’m still not there yet.

Unsui: Yes, I teach both weapons and unarmed techniques. The Jinen ryu school I created is all weapons, mainly short weapons including knife, jutte, and kusari-fundo. We also have sword. With the sword we have nito-jutsu (using two swords together) and regular sword. But the basic body movements or taijutsu comes from the other schools including Gyokko ryu, Koto ryu, Shinden Fudo ryu and so on. You should learn proper taijutsu first. When you learn using a weapon first, if that weapon gets taken away, you’ll forget the taijutsu. It’s all about how you move your feet, your body. I think I’m starting to understand this but sometimes I feel like I’m still not there yet.

7) You did research at the University of Tsukuba. Please tell us about that.

Unsui: Yes, when I turned 70, I decided to do something special to mark the occasion and entered graduate school at the University of Tsukuba. I wanted to study the mental aspect of martial arts. I studied what is considered the ideal mental state, a state called mushin or “no mind.” I experimented on the measurable, physiological aspects of it. I conducted various experiments, collected data, and wrote a paper. I finally came up with the term kakusei-mushin, where the mind is in a state of mushin, and the body is ready to go, ready to respond immediately. If you’re doing a seated meditation, your mind may be in mushin, but your body is in a state of limbo, not ready to spring into action. That is one difference.

Unsui: Yes, when I turned 70, I decided to do something special to mark the occasion and entered graduate school at the University of Tsukuba. I wanted to study the mental aspect of martial arts. I studied what is considered the ideal mental state, a state called mushin or “no mind.” I experimented on the measurable, physiological aspects of it. I conducted various experiments, collected data, and wrote a paper. I finally came up with the term kakusei-mushin, where the mind is in a state of mushin, and the body is ready to go, ready to respond immediately. If you’re doing a seated meditation, your mind may be in mushin, but your body is in a state of limbo, not ready to spring into action. That is one difference.

For many years, I didn’t understand the mental side of martial arts the way I do now. One way I often explain it is through the concept of the Buddhist god, Avalokitesvara. He has a thousand arms and they all move in different ways. The point is that his arms can only move freely if he doesn’t put his concentration into any particular arm. For freedom of movement, your attention must not get captured or stuck anywhere.

In the world of sports, you have what is called “being in the zone,” where the player is in a deep state of concentration, almost like a dream. To reach that state, you have to repeat the same motions over and over until they become natural. The techniques in kobudo are the same. You have to practice the same movements over and over again until you can do them without thinking, until you can do them with “no-mind.” That’s what I am teaching everyone now—the basic movements of martial arts until they can be done without thought.

8) How is traditional kobudo perceived today with the popularity of various modern martial arts and sports competitions?

Unsui: Ultimately, I think that people who are interested in Japanese culture come to kobudo, and people who just want to be strong or whatever go into sport martial arts. There is karate, judo, kendo, K-1, and many other sport forms of martial arts. If you head in the sports direction, it’s very different than kobudo. When you really enter Japanese culture, it starts with the heart. If your heart isn’t in it, you won’t last long. In sports martial arts, you can tell right away whether someone is strong or weak because they have matches. But that is not the basis of kobudo. Kobudo involves having a deeper connection to Japanese culture.

UDEORI to Nage-waza 1

UDEORI to Nage-waza 2

9) It sounds like it goes back to what you said before about mushin and kakusei-mushin.

Unsui: Yes, that’s ideally where you want to end up. But it is difficult to simultaneously keep your mind relaxed and present while your body is ready to respond immediately. It is really difficult. It doesn’t mean just sitting there. You have to grasp everything.

UDEORI to Kime-waza 1

UDEORI to Kime-waza 2

10) Does the Jinenkan system have ranks and levels such as shoden, chuden and okuden (beginning, middle, and advanced)?

Unsui: Yes, it does. But there are different types of divisions for the different kobudo schools. So one school may use the shoden, chuden, okuden system, while another school uses the 1-dan, 2-dan, 3-dan, system and so on. In the Jinenkan however, I chose the term “Jissen Kobudo Jinenkan” and put them all together under a single grading system. I use the kyu and dan (blackbelt) ranking system because it’s common and easy to understand. We also do testing. The test for the 1-dan (first degree blackbelt) has specific techniques taken from the different kobudo schools. That’s the system I use.

11) How many different countries does the Jinenkan have branches in?

Unsui: Besides Japan, there are dojos in America, Canada, England, France, Germany, Switzerland, Sweden, Australia…oh and recently also in South Africa. There are 36 dojo-cho instructors across the globe. Right now, a group from Australia is here and a group from Sweden is also coming this month. Japan has been on lock-down for about two and a half years, but finally the gates are open.

UDEORI to Keri-waza

12) I understand you have taught in countries all over the world.

Unsui: In the past, that was the right thing to do. But about three years ago, I stopped traveling overseas. The time difference was too much for me. My mind would get hazy and my body wasn’t able to do as well as I’d like. When I teach, I want to be able to demonstrate with the best possible form, so when I could no longer do that, I decided to stop. Also, I will stop having regular classes this year. Originally, I was planning to stop teaching when I turned 70. That was seven years ago. But I was still able to move around well, and people wanted me to keep teaching, so I continued. Now, I’ve stopped teaching regular classes, but I still teach those students who come here for private training.

13) Thank you very much for this interview.