Mugai-ryu Hogyokukai: Redefining iai

From left to right, Toshiharu Kitami, Hogyokukai president Hogyoku Takeda, Grigoris Miliaresis, Ougyoku Yasumura

Text by Grigoris Miliaresis

It isn’t as advertised as my work in “Hiden” and Budojapan but another thing I do for BAB is translating videos for its video-on-demand service. Thanks to it I have had the rare opportunity to see some schools in excruciating detail (to translate video you need to go back and forth every couple of seconds, countless times) and it was through this work that I came across Mugai-ryu Meishi-ha’s International Iaido Organization Hogyokukai and its head, 7thdan shihan Hogyoku Takeda. BAB has produced Takeda shihan’s two videos, Mugai-ryu Primer Vol 1 & 2 and watching them many times over, I got really interested in the organization’s approach to iai.

Tsuji Gettan

Like all Mugai-ryu lines, Meishi-ha traces its lineage to Tsuji Gettan (1648–1728) from Omi Province (now Shiga Prefecture) a samurai and swordsmanship instructor who studied Yamaguchi-ryu kenjutsu in Kyoto, Jikyo-ryu iaijutsu in Edo and Zen Buddhism under the founder of Kyukoji temple, Sekitan Ryozen also in Edo. The poem Gettan received from his Zen teacher when he reached enlightenment starts with the phrase “Ippo jitsu mugai” i.e. “there is nothing outside reality” and the words “mugai” (“nothing outside”) became his pseudonym and later, the name of his art. The school was changed radically by its 11thgeneration head, Nakagawa Shiryu Shinichi, (1895–1981) when it also broke into several lines; Takeda shihan’s Mugai-ryu Meishi-ha is headed by Niina Gyokuso Toyoaki (b. 1948).

It is not a secret among my “Hiden” readers that I have practiced All-Japan Kendo Federation (ZNKR) iaido for several years in what later became one of Europe’s most successful iaido dojo, Furyu Dojo Athens. Also it’s not a secret that I eventually stopped this practice because I felt it was disassociated from the realities of dealing with an opponent; my first naginata teacher had created some iai kata based on our school’s techniques which I still practice occasionally but to be frank, I have never practiced iai as part of a broader kenjutsu system.

The three pillars of iai are four

Kata: Kihon Ichi

This was what drew me to Hogyokukai’s Mugai-ryu: it has three pillars, iai kata, kumitachi kata and tameshigiri, meaning that what you learn by cutting air, you also put into use cutting an opponent (with a bokuto, of course!) and cutting a tatami makiwara (with a live blade, of course!) That would be enough to offer Mugai-ryu exponents something most iai practitioners lack, but Takeda shihan takes things to a whole new level thanks to his background in Kyokushinkai karate, complete with tournament victories and teaching experience: he has introduced the element of “jiyu (free) kumitachi”, the closest equivalent to “tournament iai” I’ve seen.

ZNKR also has “iaido tournaments”: two iaidoka perform the same kata side-by-side and the best performance wins. But despite its indisputable value, I can’t view this activity as budo and it certainly doesn’t offer iaidoka the opportunity to see how their swordsmanship measures against an opponent. Of course one could argue that since this is ZNKR, most iaidoka are also kendoka so they have plenty of partner practice when they put on their kendo bogu but be that as it may, I still think kumitachi are a better way to test your iai skills. But even there, you are lacking the freestyle element: kumitachi are also kata and thus, by definition, predictable.

(Not so) free improvisation

Jiyu kumitachi

Enter Takeda shihan’s jiyu kumitachi: using improvised swords like those used by Toyama-ryu in their gekiken, loops that function as improvised saya, karate head and hand protectors for safety and some basic rules, he has created a type of competition centered on Mugai-ryu iai: the ability to draw fast, cut your opponent and avoid being cut by him afterwards. In other words, a simulation of what would probably have been a sword fight back in the day when Mugai-ryu swordsmen where walking in the streets of Edo.

Innovative ideas aside, the 58-year-old shihan from Fukuoka is as traditional as they come in terms of practice organization: first comes etiquette (sitting, bowing, saluting the sword, putting it in the obi), then comes walking, basic sword-handling (drawing, cutting, re-sheathing), then the basic iai kata, then yakusoku (prearranged) kumitachi and after these have been digested, students move to tameshigiri and jiyu kumitachi. This was how we worked on things when we visited Hogyokukai’s main dojo in Kuramae, near Asakusa and were welcomed by Takeda shihan himself, 5thdan instructor and head of Hogyokukai’s Kanto Block Ms Ougyoku Yasumura and their student Mr. Toshiharu Kitami.

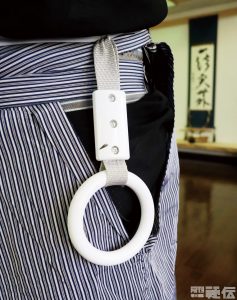

Improvised jiyu kumitachi saya

As is immediately understood even through the videos, there is a structure in Mugai-ryu’s material –there are principles that connect the iai kata (organized in four sets of five kata: Goyo, Goka, Go-o, Hashiri Gakari) to the kumitachi (organized in three sets of five kata: Tachi Uchi no kata, Wakizashi no kata and Kenjutsu no kata and one set of twelve kata: Shinto-ryu). Putting emphasis on “isshun” the one moment when the sword leaves the scabbard and cutting at shodachi, the first technique, transforming your movement according to the opponent, luring the opponent, moving to his side and preferably to his back are elements found in iai and then in kumitachi and then in jiyu kumitachi and then in tameshigiri.

Kata: Kihon Ichi

Kata: Kihon Ichi 1

Kata: Kihon Ichi 2

Kata: Kihon Ichi 3

As often happens in classic schools, the first kata taught, Kihon Ichi (Basic One) is also the last, the Banpo Ki Itto (The Countless Return To The One). In our practice, we of course worked on the former which is a standard standing iai kata: from a natural standing posture you bring your hands to the sword, immediately unlock it pushing with your thumb the handguard from behind (Mugai-ryu calls this “Hikae giri”) and not from its outer or its inner rim, take one step with the left foot while drawing and then another step with the right foot and cut horizontally with a Yoko Ichimonji cut, take another step with the left foot to bring the sword over the head with its blade parallel to the ground and then take a last right step and cut down in a vertical Makko cut. Then you lower the blade to the fallen opponent, take a right step back and do chiburi, then noto and then bring the right foot up to the left.

Hikae giri

The details Takeda shihan emphasizes are those of all iai, classic or modern: adequate sayabiki (pulling back of the scabbard) when unsheathing the sword, good hasuji (cut trajectory), big cutting movements, precision, correct metsuke (way of looking) and zanshin (awareness) after the action is completed. To make students have a better understanding of their movements in time, the head of Hogyokukai is using a metronome and anyone who has studied music knows that practice with a metronome is the best way to cultivate a correct sense of time.

Kumitachi: Kasumi

Kumitachi: Kasumi 3

Kumitachi: Kasumi 1

Kumitachi: Kasumi 4

Kumitachi: Kasumi 2

Kumitachi: Kasumi 5

Takeda shihan used the structure underlying Mugai-ryu to pass from solo iai to yakusoku kumitachi: in the kata Kihon San (Basic Three) there is a technique where with the drawing movement you cut downwards at the opponent’s wrist while moving to the left of the center line –this is the best illustration of the “isshun” concept where you cut at the first step, incapacitating your opponent with one move, in one instant. The same move appears in the kumitachi “Kasumi” (Mist) and this was the one we worked on using bokuto with saya. Here, shidachi (you) and uchidachi (your opponent) start at ten steps and walk towards each other; interestingly, when you start walking, you pull up your hakama’s right leg with your right hand. When you see uchidachi ready to draw, you draw first cutting downwards at his wrist, he retreats one step to jodan (high posture) while you pressure him one-handed, you open the tip of the sword to the right to lure him in and when he goes for your head, you step to the left and control the underside of his right arm with a two handed upward cut in a Kasumi Kamae posture.

The give and take in correct timing is the most important point in Kasumi but what Takeda shihan puts extra attention on is the right angle and the right distance when delivering cuts at uchidachi’s wrist and arm. And to better illustrate this, we pass from the yakusoku to the jiyu kumitachi. Leaving the bokuto aside, we put on a soft sash (the Hogyokukai also does this as competition so sashes are white or red) with a ring hanging from it as the improvised sword’s “saya”. We start with the hands on the sword, draw and aim to cut at the opponent first –everything must be over in the first or second technique so the whole thing will remain an iai competition and won’t go into kendo territory.

Jiyu kumitachi -and tameshigiri

Jiyu kumitachi 3

Jiyu kumitachi 1

Jiyu kumitachi 4

Jiyu kumitachi 2

Jiyu kumitachi 5

Going back to the matter of angles and distances in the yakusoku kumitachi, Takeda shihan asked me to go for the downwards cut at his wrist, the first technique of Kasumi and Kihon San. I did it but stayed in place –and he cut me back! So yes, I did the technique as per the yakosoku kumitachi but I didn’t think to also move out of the way; when we reversed roles, he cut my wrist but he immediately pushed me off balance his other hand and moved way further to my back thus making sure that he was safe; I tried it myself and it worked as good for me as it did for him before, proving this teaching approach’s merit.

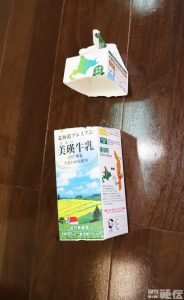

The last part of our visit was dedicated to tameshigiri; this is something I’ve wanted to try properly since my only experience was over 15 years ago, using a Chinese “cutter” sword and without a proper tatami makiwara. Even though the Hogyokukai believes that the real tameshigiri challenge is cutting an empty milk carton with a Yoko Ichimonji cut in one movement as you draw while in seiza (Takeda shihan demonstrated that perfectly), for my sake Yasumura sensei and Mr. Kitami set up a real makiwara on which I tried my hand using Takeda shihan’s shinken, one of the swords made in Yasukuni Shrine between 1933 and 1945. My cut was a Kesa and I won’t lie: it took four efforts to get a good cut and one more to get a really good one –and I won’t comment on my strained face expressions while cutting! At least my training kicked in and I kept good zanshin while doing chiburi and noto afterwards!

Tamesigiri (empty milk carton) 1

Tamesigiri (empty milk carton) 2

Cut empty milk carton

Tamesigiri (makiwara) 1

Tamesigiri (makiwara) 2

Cut makiwara

In conclusion

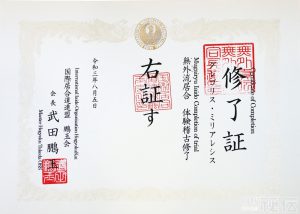

Experience completion certificate

Even in such a condensed form, it’s easy to see why the Hogyokukai approach to Mugai-ryu Meishi-ha is becoming more and more popular. The curriculum is broad and structured enough to cover most people’s idea of studying the art of the Japanese sword and if you add Tsuji Gettan’s involvement with Zen, his prominence as a swordsmanship instructor among Edo period daimyo lords and the possibility that one of the core members of the Shinsengumi, Saito Hajime (1844-1915) was among its exponents, you get a heady mix that will appeal to anyone looking for a school with both a past and a present. As for its future, at least shihan Hogyoku Takeda is trying his best: between the introduction of jiyu kumitachi that immediately became a favorite among students, advanced and beginner alike, the instructional videos featuring his lively and easygoing attitude and the Hogyokukai’s active online presence there is probably basis to his claim that theirs is the “largest organization of traditional iai in Japan”.

From my part, I can honestly say that this approach to iai is the most interesting I have seen: it addresses mine (and probably most people’s) objections and doubts on the art as an abstraction by offering a package that includes both prearranged and free form partner practice and target practice using real swords. Balancing that with a friendly and inclusive attitude and an openness towards new ideas, perhaps Hogyokukai can become a model for other classical schools in the beginning of the 21stcentury. The challenges these schools have to face nowadays are unique and to weather them they must employ new tactics –like Mugai-ryu says, transforming your self according to your enemy is the principle of the art of war and when it comes to enemies, few are more formidable than time.

PS

Once again, I want to personally thank Mugai-ryu Meishi-ha International Iaido Organization Hogyokukai’s president Hogyoku Takeda, Ms. Ougyoku Yasumura and Mr. Toshiharu Kitami. They were warm, welcoming and patiently did everything they could to accommodate us and were even kind enough to provide me with a certificate of completion of my experience –I can assure them that I will always carry a fond memory of our visit to their dojo even without it!

Grigoris Miliaresis

About the author

Grigoris Miliaresis has been practicing Japanese martial arts since 1986. He has dan grades in judo, aikido and iaido and has translated in Greek over 30 martial arts’ books including Jigoro Kano’s “Kodokan Judo”, Yagyu Munenori’s “The Life-Giving Sword”, Miyamoto Musashi’s “Book of Five Rings”, Takuan Shoho’s “The Unfettered Mind” and Donn Draeger’s “Martial Arts and Ways of Japan” trilogy. Since 2007 his practice has been exclusively in classic schools: Tenshin Buko-ryu Heiho under Ellis Amdur in Greece and Kent Sorensen in Japan and, since 2016, Ono-ha Itto-ryu under 17th headmaster Sasamori Takemi and 18th headmaster Yabuki Yuji.

http://about.me/grigorismiliaresis