Meeting the Master of the Book of Five Rings

Few Samurai in Japanese history have captured the imagination of Japanese and people around the world like Miyamoto Musashi. His classic work the Book of Five Rings was written to his student as a guide to strategy, shortly before Musashi died in 1645. It survived to serve as an inspiration to Samurai, and in later times to martial artists around the world. Musashi became canonized as a Kensei, or Sword Saint. The Book of Five Rings is cryptic and profound enough to have supported numerous translations and interpretations. Musashi’s work has found meaning not only to practitioners of the Sword and Martial Arts, but also metaphorically for business and daily life.

Few Samurai in Japanese history have captured the imagination of Japanese and people around the world like Miyamoto Musashi. His classic work the Book of Five Rings was written to his student as a guide to strategy, shortly before Musashi died in 1645. It survived to serve as an inspiration to Samurai, and in later times to martial artists around the world. Musashi became canonized as a Kensei, or Sword Saint. The Book of Five Rings is cryptic and profound enough to have supported numerous translations and interpretations. Musashi’s work has found meaning not only to practitioners of the Sword and Martial Arts, but also metaphorically for business and daily life.

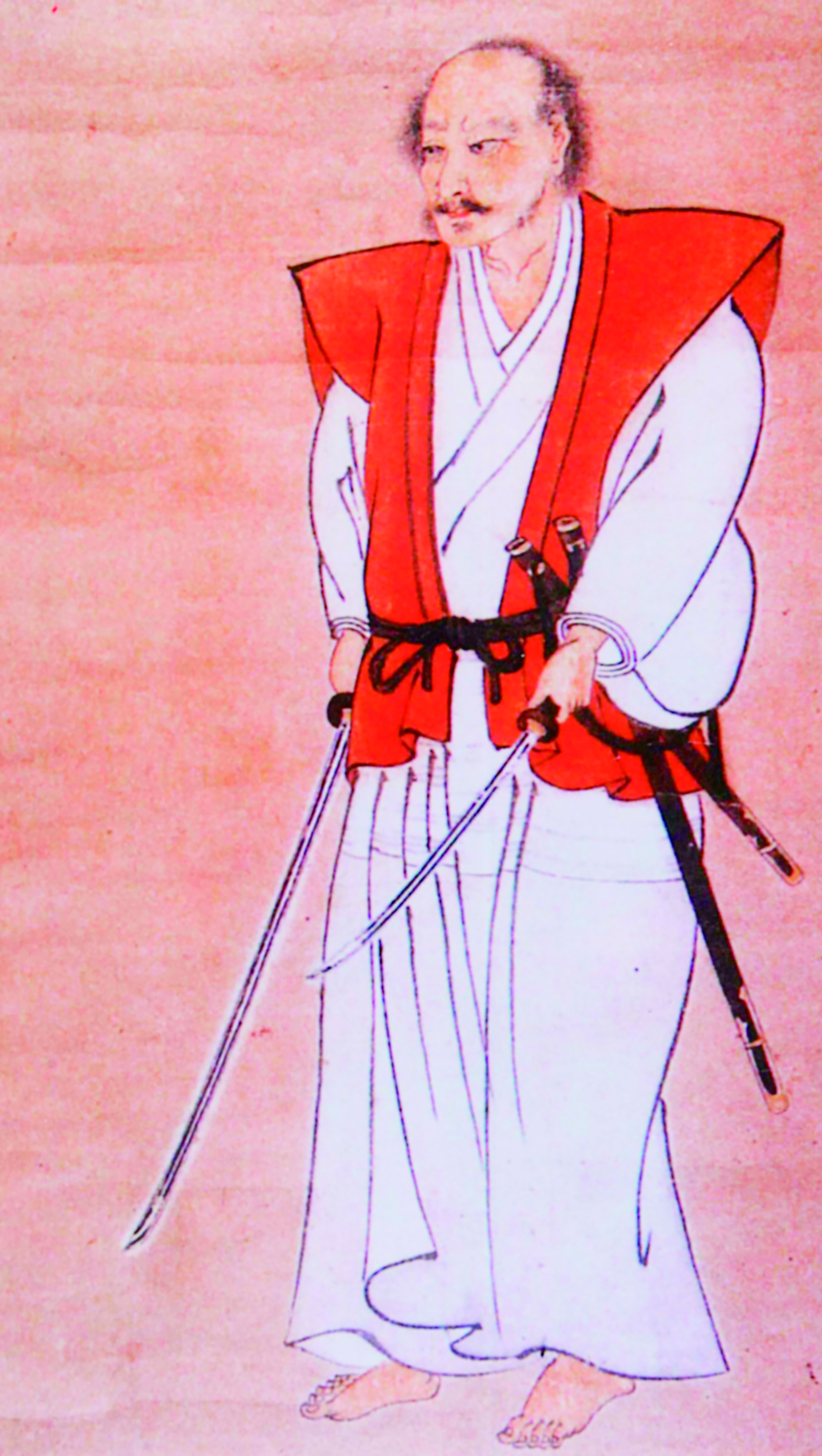

The image of Musashi comes to us as a blend of historical fact and fiction. His life combines elements of suspenseful heroism, spiritual insight, and the romance of a ronin warrior. Fiercely independent, he pioneered his own path. The legendary story of Musashi spoke to hearts and minds through Japanese art and theater in the Edo Period. Even now his story is most celebrated through the perennially popular novel Musashi, by Yoshikawa Eiji, first serialized in the Asahi Newspaper in 1935. As a book it has never gone out of print. English-speaking audiences have enjoyed this epic novel of the Samurai Era, as well as a number of film versions inspired by the book such as the Samurai Trilogy directed by Inagaki Hiroshi and starring Mifune Toshiro: Musashi Miyamoto (1954), Duel at Ichijoji Temple (1955), and Duel at Ganryu Island (1956). The long-running epic manga Vagabond, by Inoue Takehiko, also based on Yoshikawa Eiji’s novel, has brought Miyamoto Musashi further to life in the public imagination.

Miyamoto Musashi is best known for his extraordinary mastery of the sword, undefeated in 60 duels fought between 1604~1613. Often using a wooden sword against a live blade, his signature style involved using two swords, as well as psychology and strategy to defeat single or multiple opponents. But his legacy goes beyond his swordsmanship. Musashi was also a Master Calligrapher, Painter, and Sculptor. While only a few of these masterpieces survive, these works speak to us powerfully over the centuries. Musashi’s stubborn independence and level of mastery endeared him to Confucian Scholar Hayashi Razan. Musashi’s writings seem to have been influenced by Zen Master Takuan Sōhō, although there is no record that they ever met in person. In his later years Musashi entered the service of the Ogasawara, and later the Hosokawa Domains.

Reading the Words of Miyamoto Musashi

Musashi wrote The Book of Five Rings with a brush, as was common in Japan until modern times. He also left a legacy of masterful paintings and calligraphy, which tell us much about Musashi’s living philosophy and character. To really understand the mind behind the brush, it is important to have a picture of his life and times. The Lone Samurai: the Life of Miyamoto Musashi, by William Scott Wilson, is an insightful biography of this extraordinary Sword Saint. Beginning at the age of 13, he was undefeated in 60 matches fought over a nine-year period. He lived another 30 years beyond that, expanding his reach into Zen Buddhism and related arts such as ink painting and sculpture. His story is an inspiration for anyone in search of truth and continuous improvement.

Musashi’s classic work was translated and annotated by modern martial arts master Kenji Tokitsu,The Complete Book of Five Rings, lending clarity and power to many portions of the book that would otherwise remain obscure through a straight translation of the original text. The book makes many subtle but profound distinctions, such as utsu to atari (a strike and a hit), kan no me to ken no me (to see and to look at), and kage o ugokasu (moving your shadow). The annotations take you deeper into the meaning by putting them into context, adding background information, and making the explanation accessible to modern readers.

To read the original brush writing without a printed rendition and interpretation of the text is beyond even most modern Japanese. Nevertheless, it is intriguing to encounter the writing of Miyamoto Musashi in his own hand, and the characteristics of the handwriting offer many clues to the character of the man.

Reading the Character of Miyamoto Musasahi

The next layer is to look into the character and psychology of the person, by examining certain features of the brush writing, which reveal the character in the way that the strokes are written. Graphology, or handwriting analysis, provides insights into the human character behind the written characters The Japan Graphologists Association has pioneered the field of Graphology applied to Japanese Kanji characters.*

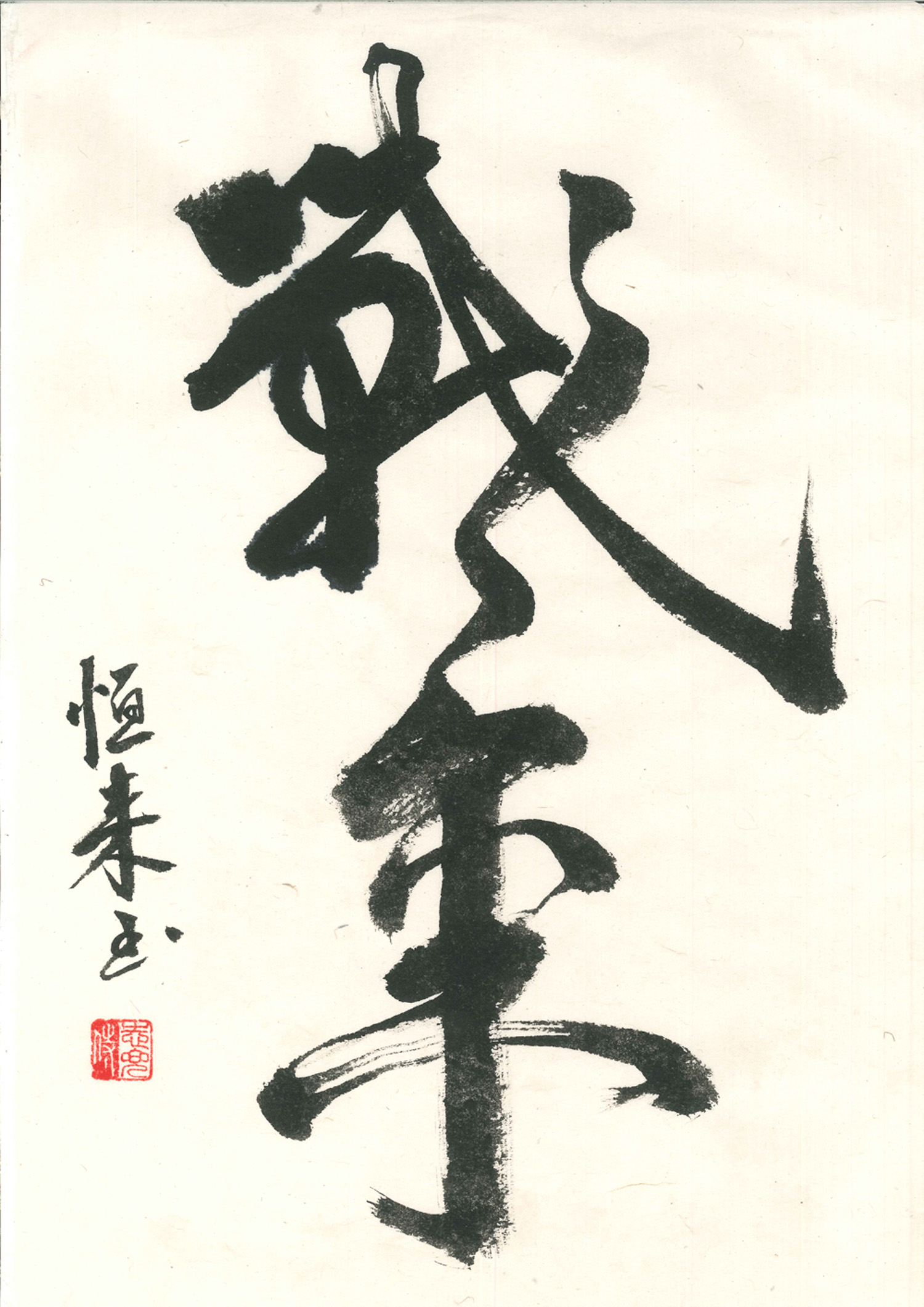

Fighting Spirit (Senki, Matsui Bunko Collection)

A famous work by Miyamoto Musashi begins with the characters for 戦氣 (senki), meaning fighting spirit, or the spirit of battle. This piece is signed by Musashi, and is in the collection of the Matsui family, housed in the Shimada Art Museum in Kumamoto. Several things strike you about this calligraphy, especially when you try to duplicate it with a brush. The two characters are written in virtually one continuous stroke, and yet the strength of the line is continuous and rhythmical. This is only possible by the concentration of deep engagement and continuous exhalation.

A famous work by Miyamoto Musashi begins with the characters for 戦氣 (senki), meaning fighting spirit, or the spirit of battle. This piece is signed by Musashi, and is in the collection of the Matsui family, housed in the Shimada Art Museum in Kumamoto. Several things strike you about this calligraphy, especially when you try to duplicate it with a brush. The two characters are written in virtually one continuous stroke, and yet the strength of the line is continuous and rhythmical. This is only possible by the concentration of deep engagement and continuous exhalation.

The strokes are bold and continuous, but a balance of thick and thin strokes reveals an exceptional sense of rhythm and agility, a mind that can find it’s way in and out of trouble. The strokes are tightly laced, giving you a feeling for what Musashi calls nebari, a pasty persistence that sticks to the core and does not let go.

The right-hand radical extends high above the left, suggesting an independent spirit. The right sweeping stroke in the first character is quite long, expressing a tendency to push farther than most in pursuing the craft. The position of the stroke to the upper right is rather closely held, and the two radicals are relatively close together, suggesting a person who is more inwardly focused, and not concerned with outward appearances. Even when thick lines cross closely, the internal white spaces are well defined, and preservation of internal white spaces reflects physical and mental vitality.

The character for 氣 (Ki) may appear truncated or abbreviated. This is partly because that is how the character is written in the highly cursive Sousho style. Musashi’s preference for cursive brush writing is a reflection both of his intense internal focus, and how his own sword movements must have been extraordinarily difficult for an opponent to read. It also reflects his brilliant use of strategy and psychology to upset and unbalance an opponent, always doing the unexpected.

The characters below Fighting Spirit (senki) read:

Cold currents envelop the moon

Clear as a mirror

This is a poem by Hakukyoi, which represented to Musashi the essence of a calm mind. Along with the highly-cursive lines, the characters are rather tightly spaced, perhaps a reflection of Musashi’s ability to tightly shadow his opponent’s moves. Thick strokes mix freely with thin strokes, and internal spaces are well preserved, which further reinforces the impression of a sword master who could remain calm and effective at the edge of life and death. Musashi knew how to be close enough to safely penetrate the opponent’s space and deliver a fatal strike.

The way the characters follow closely one on another reflects a sense of urgency and activity. The first and third characters display long horizontal strokes from the left, a sign of proactivity, starting or perhaps arriving earlier than expected. The final stroke of the last character, which means mirror, trails up at the end to form a long ladle-like shape. This way of ending a stroke was also characteristic of Toyotomi Hideyoshi, who unified Japan during Japan’s Sengoku, or Civil War Period. It reflects the capacity of a man capable of great things.

Memorandum (Oboegaki)

Unfortunately, the only calligraphy of the Book of Five Rings surviving are copies. The original manuscript written in Musashi’s hand did not survive. Also in the Shimada Art Museum collection is set of instructions written by Musashi for his student, the piece known as Memorandum (Oboegaki). It was written shortly before the Book of Five Rings and contains the essential principles. It is written in cursive calligraphy, and you can see where Musashi dipped the brush for ink by the wet darker strokes, and how the characters gradually fade into drier but equally firm strokes. He writes as many as 13 to 14 characters before dipping the brush for more ink. The gradual release of ink without losing power is comparable to that of a long distance runner with a second wind, able to sustain motion without running out of breath. The lifeline, or kimyaku, is never broken. The columns of characters stay close to the vertical line, which is the result of deep focus without distraction. This is more than a sign of strong energy. It reflects his lifelong tendency to persist in the pursuit of perfection, and to carry his actions past the limits of ordinary men. Even the thin lines are sharp as a blade. The vertical columns of text also breathe with a dynamic sense of rhythm, a proactive and powerful force he called tempo or rhythm (hyōshi).

Shrike on a Dead Tree (Koboku Meigekizu)

While he wrote letters and books in brush calligraphy, his real masterpieces were in ink painting, an art that shares much in common with calligraphy. His pictures of birds, in particular the Shrike on a Dead Tree (Koboku Meigekizu), reveal a state of mind that goes beyond alertness to encompass life and death. It is almost mind itself, reducing a dozen opponents to a single state of awareness. Likewise his Bodhidharma Portraits have a riveting and all encompassing gaze, from which it is impossible to hide.

* Analysis of specific qualities of Miyamoto Musashi’s brush writing was provided under the supervision of Ishizaki Senu Sensei, an experienced and Certified Graphologist, who is also my Calligraphy teacher.

Reading the Mind of Miyamoto Musashi

Attempting to duplicate the shape and rhythm of Miyamoto Musashi’s brush writing takes a special form of concentration, knowing that you are facing an undefeated master of the sword. His calligraphy is visceral. It has a special effect on your breathing, and even in a cool room you may work up a sweat just rendering the two characters of fighting spirit.

I recommend approaching the process in three stages. Start by tracing the strokes in the proper order with your finger directly on top of the photograph of the calligraphy, or better yet an enlarged copy that can lay flat on the table. The purpose of this is to get perfectly clear on the stroke order. If you hesitate on the stroke order, your mind will waver and you will defeat yourself.

Once you are clear on the stroke order, try making a faithful copy with a drawing pencil on high quality paper. The pencil is easier to control than a brush, and quality materials will allow you to get a sense for the rhythm, rise and fall of pressure in the strokes. Take care that you do not draw everything at the same speed or pressure, as the rhythmic quality is essential in getting the right feel of the calligraphy.

When you are ready, try making a faithful copy of the work using a brush on hanshi calligraphy paper. Identify the relative size and positioning of the strokes, and be sure to grasp the position of the characters relative to the centerline of the paper. Be very clear on where you will position the first stroke, as this will affect the position of all of the strokes that follow. Be aware of the center axis line which runs through the two characters, as well as the relative size of each character. You need to spend some time with the calligraphy for it to reveal its secrets.

Because these two characters are written in virtually one continuous stroke, you need to judge how much ink to apply to the brush so that you don’t run out of ink or breath before you complete the second character. Pay attention to the kimyaku, or lifeline which runs through all of the strokes, as well as connections them when the brush enters and leaves the paper. Maintaining the kimyaku in this case is the equivalent of surviving the match. It is also a reflection of your skill and awareness in using the brush as a sword of the mind.

After encountering Musashi through his own brush writing, go back and read the translations and annotations of the Book of Five Rings. It will speak to you at an entirely new level.

Tips on Writing like a Samurai

There are some features of Miyamoto Musashi’s handwriting that you might want to adopt in your own.

Strong Strokes and Rhythmic Control

The secret to having strong strokes well blended with thick and thin strokes is good observation and breath control.

Dynamic balance with unpredictable movement

Be sure to capture the subtle movements inside the strokes when the brush changes direction. The energy is powerful but well timed. The awareness is diffuse, seeing what is close as far, and what is far as close.

Razor sharp concentration

The challenge is to maintain a steady and sharp line no matter how thin the strokes become. This is a result of how you hold the brush, and your mental focus. To better understand how to use the brush like a Samurai, return to Book of Five Rings and study what Musashi wrote about how to use the sword.

William Reed is from the USA, but is a long-time resident of Japan. Currently a professor at Yamanashi Gakuin University, in the International College of Liberal Arts (iCLA), where he is also a Co-Director of Japan Studies. He holds a 10th-dan in Shodo from the Nihon Kyoiku Shodo Renmei, and a 7th-dan in Aikido from the Yuishinkai. He also holds a Tokubetsu Shihan rank in Nanba, the Art of Physical Finesse. A weekly television commentator for Yamanashi Broadcasting, he also has appeared numerous times on NHK World Journeys in Japan, and in documentaries as a navigator on traditional Japanese history and culture. Certified as a World Class Speaking Coach, he has appeared twice on TEDx stages in Japan and Norway, and has written a bestseller in Japanese on World Class Speaking.