Matsudaira Katamori and the Aizu Bushido Code

Matsudaira Katamori was the 9th generation Daimyo to Head the Aizu Clan. Born as the sixth son of Matsudaira Yoshitatsu of the Takasu Clan in Minonokuni, at the age of 12 he was adopted by his uncle Matsudaira Katataka, the 8th generation head of the Aizu Clan. This family was among several direct descendants of the Tokugawa, including Mito, Owari, and Wakayama. Katamori was connected by blood to the Mito Tokugawa Clan, and was an important figure in the events of the Bakumatsu Era, which preceded the modern period. However, historical background aside, let’s take a look at the character behind the brush writing of Matsudaira Katamori.

Matsudaira Katamori was the 9th generation Daimyo to Head the Aizu Clan. Born as the sixth son of Matsudaira Yoshitatsu of the Takasu Clan in Minonokuni, at the age of 12 he was adopted by his uncle Matsudaira Katataka, the 8th generation head of the Aizu Clan. This family was among several direct descendants of the Tokugawa, including Mito, Owari, and Wakayama. Katamori was connected by blood to the Mito Tokugawa Clan, and was an important figure in the events of the Bakumatsu Era, which preceded the modern period. However, historical background aside, let’s take a look at the character behind the brush writing of Matsudaira Katamori.

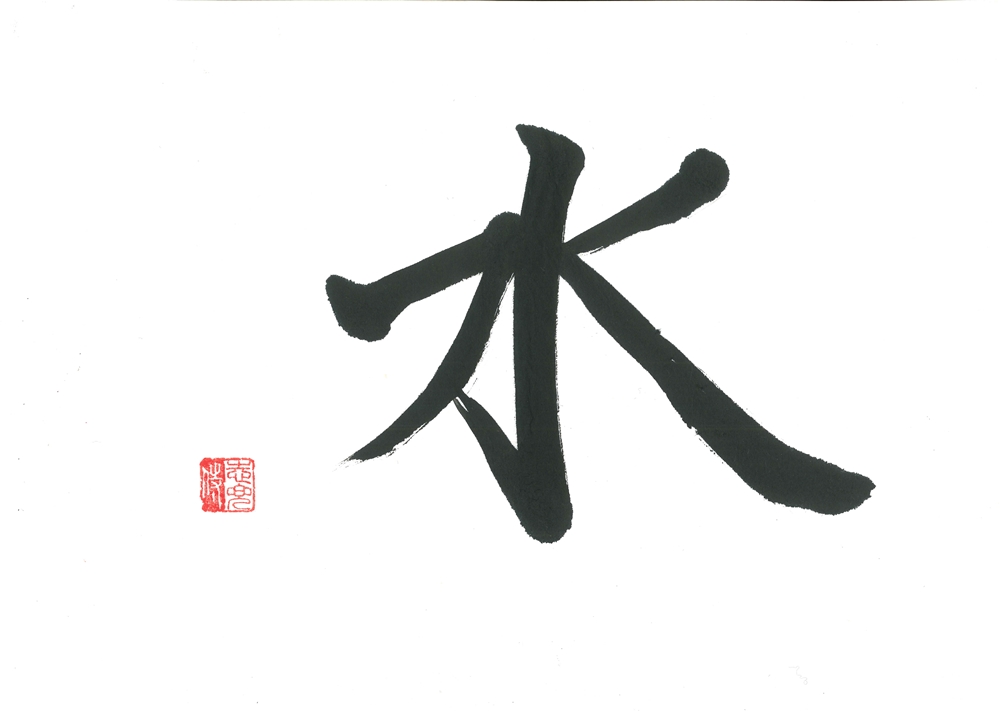

Characteristics that stand out in his brush writing include a curved vertical line, accented stroke beginnings, an extra long right diagonal stroke, top extended vertical lines, a strong whip like stroke ending on the vertical stroke, and open stroke connections between the first and the final strokes of the square mouth radical. Let’s look at these one at a time.

The central vertical stroke of the character for water 水 is painted on a curved line, like a bow drawn under tension. The same is true for the vertical stroke in the left-hand tree radical 木 of the character for Willow 柳. The curve in the vertical line is a sign of imagination and creativity, a mind brimming with ideas. The beginning of the strokes seen in the characters for water 水 and left 左 are strongly accented. The beginning of the line also reflects the beginning of an action, and these strokes are almost more like strikes than strokes. The strengths of such a personality include strong and clear thinking, as well as a sense of reliability. When these characteristics dominate however, it can lead to the stubbornness of a strong ego, a tendency to insist on one’s way, and not being open to listen to the opinions of others. An extra long right diagonal stroke is found in the character for water 水 and in the first character of his name 容. This is the sign of a person who tends to get caught up in an action once begun, and may not be able to stop despite good reasons for doing so, a reluctance to apply the brakes.

A strong whip like stroke ending on the vertical stroke is seen in the characters for water 水, General 将, and the thread radical 糸. This is a sign of a strong sense of responsibility, perseverance in the face of difficulty, and strong sense of resolve. When taken too far this can lead to not knowing when to quit, or being slow to respond.

Looking at the characters in the title for Willow 柳 and at the end for blue-green willow 青柳, you notice that the vertical stroke extends high above the horizontal stroke which crosses it. This is a sign of high energy that does not settle for low level thinking. As with the whip like vertical stroke endings, this feature often appears in people of exceptional leadership ability. The same feature appears in the characters for spring 春 and blue-green 青. A high placement of the vertical stroke over the underlying horizontal strokes is mostly a subconscious action, and frequently appears in people in strong leadership positions. By contrast, people who prefer to take a supporting role, and shy away from positions over other people also tend to make the protruding vertical stroke much shorter, sometimes only barely extending above the horizontal strokes that cross it. Check your own handwriting of these characters to see where you fall along the continuum. If you find that there is not much protrusion above the horizontal line, and you are seeking to cultivate stronger leadership qualities, you may wish to consider practicing writing with greater extension above the line. One way is not better than the other, but the longer vertical line will serve you better in a position where you must lead others.

The characters 邉, 中, 容, 保, and 河 all contain the square mouth radical 口. In Katamori’s brush writing, the stroke connections between the first and the final strokes of the square mouth radical are often left open rather than being attached to the first left hand stroke. The lower left side as well as the upper left side of the radical are often left open, while the lower right side or ending of the stroke is usually attached or closed. People who leave the strokes open have a tendency to prefer to leave matters open, and a willingness to forgive. There is in this a sense of consideration for others, and a willingness to compromise. When taken too far, this can lead to a tendency to be soft also on oneself. On the other hand, all of the strokes at the lower right are attached, which is a sign of a strong sense of responsibility. The refined line quality in the brushstrokes indicates a person of refined sensibilities.

Perhaps these characteristics give you a closer sense of the man Matsudaira Katamori. He played an important role in the developments during the Bakumatsu period. He was adopted into the Aizu Clan at the age of 12, and quickly recognized for his intelligence and strong character. When his adopted father passed away, at the age of 18 he took over the position as the 9th generation head of the Aizu Clan, and later would be swept up in the big waves that rocked the clan at the end of the Bakumatsu period. Japan faced strong pressure from America and the European powers to open its borders to trade. Katamori was head of the Aizu Clan when Commodore Perry came to Japan with his ominous Black Ships. This was during the reign of the Emperor Komei. The Bakufu Government was pressured to sign a Treaty of Amity and Commerce with America, but the Emperor Komei opposed it. Despite the Emperor’s decision, the chief minister of the Bakufu, Ii Naosuke ratified the treaty anyway, and launched a purge to capture and execute over 100 followers including many from the Mito Clan of the Sonno Joi movement to Revere the Emperor and Expel the Barbarians. This led to the assassination of Ii Naosuke outside the gates of the Sakuradamon at Edo Castle. Matsudaira Katamori was involved in the mediation amidst this turmoil, and consequently was highly regarded by the Bakufu government. With trouble brewing in Kyoto and increasingly dangerous conditions from opposition by the Sonno Joi movement, Matsudaira Katamori was appointed by the Bakufu government to serve as the Protector of the Emperor in Kyoto. Although he repeatedly tried to refuse this appointment, ultimately he accepted it. He referred to the 15 principles of the Aizu Bushido Code, reading it aloud to leading clan members. He concluded that they must defer to the position of the founding member of the Aizu Clan Hoshina Masayuki, as a direct descendent of Tokugawa Ieyasu, that their ultimate duty was to defend the Tokugawa Clan. This loyalty, and the core principle of the Aizu Bushido Code of GI 義 or Loyalty became the defining principal in his decision to accept that role.

A documentary was produced marking the 150th anniversary of the Boshin War. I was privileged to participate in the part of the documentary which focused on the education of the Aizu Samurai During the Edo Period, before the Boshin War. Although the original buildings of the Tsuruga Castle and Nisshinkan Dojo were destroyed in that war, they have been beautifully restored and take you back to the Golden Era of Aizu.

It was in the Nisshinkan Dojo that I was able to paint the calligraphy for Gi 義 the Spirit of Fidelity which runs through the Aizu Bushido Code. To gain a better understanding of the circumstances and of the Aizu Bushido Code, be sure to watch the four episodes of this documentary on the Aizu Samurai. The four episodes TAIGI「大義」DOUGI「道義」SHINGI「信義」CHUUGI「忠義」are all viewable through the site on YouTube. It was broadcast on all 4 of Japan’s Satellite Channels, as well as on The History Channel. It has stunning visuals and music, and although the narration is in Japanese, it will be released on the site with English subtitles. I appear as Navigator in the DOUGI 「道義」episode, a project which took me to Aizu Wakamatsu to interview experts at it’s most historic sites. It was an unforgettable experience, and an opportunity to absorb the spirit of the Aizu Samurai.

It was in the Nisshinkan Dojo that I was able to paint the calligraphy for Gi 義 the Spirit of Fidelity which runs through the Aizu Bushido Code. To gain a better understanding of the circumstances and of the Aizu Bushido Code, be sure to watch the four episodes of this documentary on the Aizu Samurai. The four episodes TAIGI「大義」DOUGI「道義」SHINGI「信義」CHUUGI「忠義」are all viewable through the site on YouTube. It was broadcast on all 4 of Japan’s Satellite Channels, as well as on The History Channel. It has stunning visuals and music, and although the narration is in Japanese, it will be released on the site with English subtitles. I appear as Navigator in the DOUGI 「道義」episode, a project which took me to Aizu Wakamatsu to interview experts at it’s most historic sites. It was an unforgettable experience, and an opportunity to absorb the spirit of the Aizu Samurai.

Visit these sites for further details.

http://diamondroutejapan.com/sp/history.html

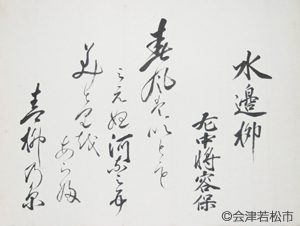

Notes on the Calligraphy Poem and the Aizu Bushido Code

Waterside Willows

by Governing Commander Katamori

The Spring breeze ruffles

The long feathered branches

Of the green willow by the riverbank

Washing its leaves as it

Conceals the river waves

Waka Poem, Calligraphy by Matsudaira Katamori.

This beautiful poem painted in a skilled hand is by the 9th generation Commander of the Aizu Clan, Matsudaira Katamori. Although the poem itself is likely to have been drawn from classical Japanese literature, Katamori’s choice of this Waka poem, and the fact that he painted many Waka offers a view of a sensitive soul.

The poem reflects a particularly Japanese sensibility of how nature at once conceals and reveals, and how the elements of wind, water, and willow mingle in a fluid natural harmony. The willow is a symbol of yielding, and of bending without breaking. The observer is part of the scenery, and nature provides a healing respite from the duties of a Samurai caught in the demands of his command.

In classical form he uses hentaigana, the highly cursive precursors to the modern hiragana, which could only be written or even read by a highly educated person. The line quality is graceful and fluid, and clearly the hand of a person with refined aesthetic sensibilities, a master of sword and letters. His creative mind may have found its outlet in his love of Waka and Calligraphy.

Given his position, he may not have often been able to exercise this imagination when it came to commands to defend the coast near Edo, or to act as the protectorate of Kyoto. Despite strong opposition from his own advisors, he stated that he had no choice but to follow the orders, for the sake of his obligation to the House of Tokugawa, and his reputation for future generations.

The characters are written in cursive calligraphy, but each one stands independent, suggesting a sense of deliberateness. At the same time, there is not much space between the characters, a sign of a person under pressure, or a full schedule.

Let’s consider the influence that the Aizu Samurai Education must have had on Katamori, as well as on all young Samurai boys who would have attended school at the Nisshinkan Dojo. Boys from officer level Samurai families from the ages of six to nine had to form groups of ten children, which met daily and were led by the oldest child. They were expected to recite and live by the rules of the Aizu Bushido Code, which were reinforced in their formal schooling at the Nisshinkan, but any violations would be subject to penalty decided by the group leader.

There were 7 rules for children in these groups, called Ju no Okite, the Aizu Code of Behavior.

* You must not disobey those who are older than you.

* You must bow to the elders.

* Do not tell a lie.

* Do not be a coward.

* Do not bully weaker persons.

* Do not eat things outside the house.

* Do not speak to women outside the house.

The rules end with a summary sentence that is became the mantra of what it means to be an Aizu Samurai, which parents would constantly use with their children.

That which is forbidden must not be done.

While this system was introduced in 1664, it was formalized in the Nisshinkan around 1800. The Nisshinkan Dojo held classes from from 1000~1300 students, who studied the Chinese Classics and calligraphy, as well as Samurai code of behavior and various martial arts. As one of 300 Clan Schools nationwide, Nisshinnkan Dojo was a model Clan School, hermetically sealed moral and liberal arts education, reinforced by the study of the Chinese Classics and the Martial Arts, including archery, horsemanship, spear, and riflery arts. The school also had a swimming pool and an observatory. This intensive training continued daily from the age of ten until the boy reached 15, and underwent the genpuku ceremony of becoming an adult.

While this system was introduced in 1664, it was formalized in the Nisshinkan around 1800. The Nisshinkan Dojo held classes from from 1000~1300 students, who studied the Chinese Classics and calligraphy, as well as Samurai code of behavior and various martial arts. As one of 300 Clan Schools nationwide, Nisshinnkan Dojo was a model Clan School, hermetically sealed moral and liberal arts education, reinforced by the study of the Chinese Classics and the Martial Arts, including archery, horsemanship, spear, and riflery arts. The school also had a swimming pool and an observatory. This intensive training continued daily from the age of ten until the boy reached 15, and underwent the genpuku ceremony of becoming an adult.

The way of thinking and behavior of an elite Samurai body was formed at the Nisshinkan Dojo, and all of the households in Aizu were familiar with the Code. Katamori was also from an Owari branch family of the Tokugawa Clan, so his behavior was also strongly conditioned by his heritage. To quell the rumors that his reluctance to take on the position as protectorate of Kyoto, he said, “If people start talking like this, it will shame our domain. There is no way I could explain this to the generations of Aizu lords who have gone before me. I have no choice but to accept.” These are the words of a man who lives very much in the public domain.

Considering his educational background and political heritage, as well as the very dangerous responsibilities to which he was to be posted, it very interesting to consider how calligraphy and poetry may have played an important role in maintaining his balance and sanity as a Samurai. This brings new meaning to the phrase bunbu ryōdō, Master of Sword and Letters.

William Reed is from the USA, but is a long-time resident of Japan. Currently a professor at Yamanashi Gakuin University, in the International College of Liberal Arts (iCLA), where he is also a Co-Director of Japan Studies. He holds a 10th-dan in Shodo from the Nihon Kyoiku Shodo Renmei, and a 8th-dan in Aikido from the Yuishinkai. He also holds a Tokubetsu Shihan rank in Nanba, the Art of Physical Finesse. A weekly television commentator for Yamanashi Broadcasting, he also has appeared numerous times on NHK World Journeys in Japan, and in documentaries as a navigator on traditional Japanese history and culture. Certified as a World Class Speaking Coach, he has appeared twice on TEDx stages in Japan and Norway, and has written a bestseller in Japanese on World Class Speaking.