Iwama-ryu Aikido: Irimi-nage – The Eye of the Hurricane

Text by Tim Haffner

After a recent evening training session at the Tanrenkan Dojo, amid the cold December air in the north of Japan’s Ibaraki Prefecture, I was fortunate to gain additional insights on some technical and philosophical Aikido principles from Saito Hitohira, Kaicho of the Iwama Shin Shin Aiki Shurenkai.

Kaicho, along with his wife Hisako-san, prepared a meal of sardine and bonito sashimi, a potato-based okonomiyaki pancake with horseradish sauce that was inspired by some recent Russian live-in students, meat stew, and fried noodles with spicy black pepper. We gathered around the wood tables of the Shin Dojo, located adjacent to the Saito family home and across from the Aiki Shrine, and enjoyed the food amid conversation while watching flames dance through the window of the wood burning stove that had recently been cleaned by diligent live-in students who had since returned to their home countries of Russia and Germany.

Saito Kaicho and Hisako-san

A Quiet Celebration in the Shin Dojo

Katate-dori Irimi-nage

After a time, Kaicho spoke about the technique practiced during that night’s keiko (稽古). I had partnered with Kaicho’s son, Morihiro Ni Dai Me (Yasuhiro) and worked on several variations of Aikido’s “entering throw” (Irimi-nage・入身投げ) from a same-side, single wrist grab (katate-dori・方手取り). In this technique there are generally three basic hand escape methods (te-sabaki・手捌き) exercised from high, then low, and finally middle positions (上,下,中).

While single wrist grabs from the front may appear insignificant amid modern martial arts and sport fighting, it is important to remember Aikido’s samurai roots where an attack that immobilizes one’s arms prevents the defender from accessing their belt carried weapons thus rendering them vulnerable to further, more decisive, attacks. Therefore, escaping from arm or wrist holds in order to regain unfettered access to the tools of their trade, and thereby control the outcome of the confrontation, was a vital skill for Japan’s historical warrior class. This also remains a significant contribution Aikido offers to armed professionals and responsible citizens throughout the world today.

The Katate-dori Attack, uke: Ken Campbell, shite: Tim Haffner

Katate-dori Follow On Attack

The real threat of wrist grabs: immobilized, disarmed & vulnerable.

Katate-dori Sabaki: Moving to get free, gain control, and retain your weapons.

The Attack Illustrated

Outlaw King (2018): Same side arm grab and dagger disarm.

A good example of this type of attack can be seen in the movie Outlaw King where Scotland’s historic Robert the Bruce dispatches a rival lord, John Comyn, while the two were arguing face to face. Bruce grabs Comyn’s arm while reaching for the dagger on the latter’s belt and then stabs up the center line into the brain, killing him with a single swift blow. While the movie is an historical dramatization, it offers an excellent illustration of the devastating nature of single arm grabs as an adjunct to ensuing attacks.

Basic Programming

Programming effective responses to this type of sudden ambush requires skill building through reinforcing repetitions. In the approach characteristic of Iwama-ryu Aikido, opponents are allowed to take a strong hold so as to create the most unfavorable conditions to be overcome. The basic practice (kihon waza・基本技) is about learning how to move out of danger and into a position of advantage, despite significant resistance from the opponent. This compels deep adoption of the technique through strict adherence to the prescribed form.

After a period of ingraining the basics from a static hold, the same technique is practiced with the movement beginning incipient to the attack. These blending practices (awase・合わせ) offer the opportunity to lead the opponent’s energy and apply the technique while in motion. In this, care must be taken to avoid disconnecting from the attack by moving too quickly and altering the attacker’s decision cycle. Trying to avoid the attack by pulling away too soon offers the opponent the opportunity to reorient on a new target. Therefore, blending with the attack with the correct timing necessitates drawing the opponent into our sphere of influence, using calm and subtle movement.

During the training session I received corrections advising that in all three variations, once freed from the grab, the opponent’s wrist should be firmly held, and the arm fully extended at approximately chest height. Some readers may reference the difference here with the book series published in the 1970’s or 1990’s to notice that, in those volumes, an upper position (上段) release does not grab hold of the attacker’s wrist but uses a sword hand (tegatana・手刀) to guide the opponent’s wrist slightly down and to the outside.

From Aiki Journal’s 1996 Takemusu Aikido Volume 2: More Basics, uke: Pat Hendricks, shite: Saito Hitohiro

Rhythm and Flow

Also, just as the Zen monk Takuan Soho in The Unfettered Mind described the time interval between actions as analogous to that of a spark emitting from a stone striking a flint, so too must the freed hand immediately move to grab ahold of the opponent’s collar. The two firm holds, wrist and collar, then reinforce the action of unbalancing the opponent forward before throwing them down with a reverse stepping movement and applying The Founder’s oral instruction (kuden・口伝) to turn the thumb down and make “your arm like a ring of iron” (親指は下を向くように、腕は鉄の輪のように).

In the current mode of training aikido’s “entering throw” at the Iwama Tanrenkan Dojo, the grips on the opponent’s wrist and collar create dynamic tension by simultaneously engaging countervailing forces. That is, as mentioned previously, the opponent is unbalanced forward and slightly to the outside while also stretching their body to the front and rear. This creates the “kuzushi (崩し) effect” of disrupting their equilibrium, moving them out of their power base, and making their bodies float (ukimi ・浮身), thereby making them easy to throw.

One other distinguishing feature of this approach is that the opponent’s chest appears to form a nearly flat shelf and their heart center faces upward. This is very different from other ways of doing irimi nage where the opponent is brought to face down. Such a condition then requires tremendous effort to lift them up before throwing them down to the rear. By stretching them out to the front and holding them floating under dynamic tension, the throw becomes a matter of flowing with their natural inclination to sink down and the rear, in search of their balance point.

This action should occur within two beats and not three. Oftentimes, when practicing the basic form of this throw from a static hold, there is a tendency to break the action into three segments consisting of the hand release, followed by the unbalancing, and then the actual throw. This can be identified by three distinct “kiai” shouts (気合) coinciding with the movements. However, the hand release and unbalancing need to be considered and trained as though they were one contiguous action. Rather than three kiai there should be one slightly longer vocal exhalation followed by a shorter one.

The hand release and balance displacement, as one action, then sets up the opportunity, the “aiki” moment, for blending with the attacker’s reaction to being unbalanced. Developing this sensitivity through rigorous training from a static hold leads to a degree of sensitivity and alertness necessary to successfully apply the principles in a dynamic fashion, when the energy is flowing (ki no nagare ・気の流れ).

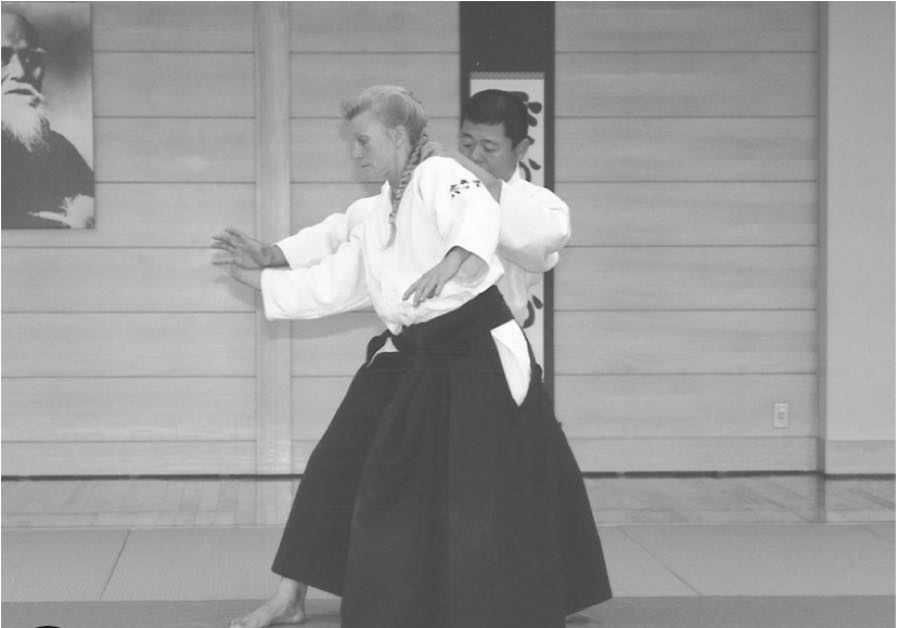

Katate-dori: uke: Tim Haffner, shite: Saito Morihiro Ni Dai Me (Yasuhiro)

Katate-dori Jodan Te-Sabaki (Hand Insertion)

Katate-dori Jodan Te-Sabaki (Hand Insertion)

The Irimi-nage Kuzushi position.

The Irimi-nage throw

The moment of Zanshin after throwing with Irimi-nage.

Open to Enter

Many approaches to aikido emphasize the need to maneuver in the midst of an attack from in front of the opponent to the rear by stepping into what is known as the ‘dead angle’ (shikaku ・死角). This position typically aligns the defender’s center line with the attacker’s forward shoulder blade and is the preferred spatial relationship for gaining the initiative and dominating the combative engagement. This is what aikido founder, Ueshiba Morihei O’sensei referred to when advising to ‘enter deeply and turn’, or to ‘stand behind the enemy’s form and so cut them down’ in his poems (doka・道歌).

The step into shikaku, particularly in the initial stages of learning, often involves large leg movements around the outside of the opponent in order to get to their rear. English speakers will often quip that “irimi” means the responsibility is on “me”, I have to do the entering to set up the throw. These training methods remain valuable yet evolving this technique must aim toward accomplishing another dictum from O’sensei’s poems: Draw the opponent outside their sphere of strength and into your own.

To that end, guidance during the evening’s training session involved more opening and less entering to accomplish the ‘entering throw’. Rather than “stepping” to the rear of the opponent, one aligns the toes in a similar fashion to how the basic ‘tai no henko’ body changing practice is done at the beginning of every ‘taijutsu’ class in the Iwama-style. Rotating one’s hips, by pivoting on the ball of the big toe, combined with the ‘te-sabaki’ hand release leads the opponent off balance to the front, drawing them off balance in a fashion akin to when a skier gets ‘ahead of’ their ski tips.

Another aspect of accomplishing this forward unbalancing of the opponent is by opening the body. Many beginning irimi-nage practices appear to be ‘two-directional’ exercises: Facing an opponent to the front, you step behind to face the same direction as they are, unbalancing them to the rear from the ‘dead angle’, and winding up with your two front feet essentially aligned along parallel lines before completing the throw.

The simplified beginner’s technique involves a 180-degree turn. In contrast, the more evolved technique is more akin to a 225-degree opening. You wind up in the same spatial relationship with the attacker, the “shikaku” dead angle, yet the movement involved to get there is completely different.

Becoming the Eye of the Hurricane

Beginner practices for entering, by stepping to an attacker’s rear, are fine, yet embodying the Founder’s concept requires refinement. A fundamental idea in Budo (武道) is to always assume multiple attackers are potentially present. Committing to move behind one opponent may put you into the zone of a coordinated ambush. Therefore, ‘drawing out the opponent’s attack’ is a survival tactic not a mere philosophical notion.

Expressing this in technique entails aligning the toes of the forward foot with that of the opponents’ digits, in the same fashion as tai no henko. In this way, tai sabaki body opening and te-sabaki hand escapes enable freedom movement that essentially seizes the initiative even amid a surprise assault. This then allows follow on responses to any other attackers that may be involved.

The Shikaku position from a Katate-dori attack.

One must have a high degree of situational and environmental awareness to apply aikido. You must be cognizant of threat vectors from all directions simultaneously. Not just a circle of awareness is required but an expansive sphere. You do not want to be on the edge of the commotion but occupy the center. It is this center, the eye within a hurricane of activity, that you must create with your presence.

Soul, Soil, and Stamina

This is what O’sensei meant when describing the Eight Powers (八力) in Shinto cosmology. Again, it is not just philosophical but imminently practical. The eight powers (merging-separating, hardening-softening, tensing-relaxing, and movement-stillness) are active multiples of eight extending out in infinite directions. The entire sphere, not just a circle but overlapping circles expanding in all directions. This is another reason to daily practice meditation (chinkon ・鎮魂), with the same devotion as the Founder. Settling the spirit puts us in touch with the natural rhythm, cycles, and activities of the universe so that we can then take skillful action.

O’sensei pursued Budo and farming in Iwama. It is a path of production and protection. We serve humanity by cultivating the soil and ourselves through arduous effort. We cannot just throw seeds on the ground and expect them to bear fruit. Expecting to jump straight into the blossoms is pure delusion. We have to till the soil, and it is hard work, yet necessary if we want to enjoy the harvest.

The Founder’s ideas largely derive from rural samurai (地侍) tradition. Only a small percentage of the population were ever samurai. Aikido principles may, indeed, be universal, yet few are up for the challenge of continuous discipline. We cannot expect everyone to have what it takes to follow the path. Of every ten people that come to train, maybe two or three will stay, and this is alright. Here, in Iwama, we will nevertheless continue to cultivate O’sensei’s vision.

Shurenkai: https://iwamashinshinaikido.com/

volumes: https://academy.aikidojournal.com/takemusu-aikido-books

Iwama: https://iwamashinshinaikido.com/

About the author: Tim Haffner is a retired US military and law enforcement officer living in the west Tokyo area. He holds a 5th Dan in Iwama Aikido and also trains in Tennen Rishin Ryu swordsmanship.