Budo tourism: what do the budoka think? A conversation between Lance Gatling, Sandro Furzi and Michael Reinhardt

text by Grigoris Miliaresis

We had started working on the subject of budo tourism at the time when the Covid pandemic hit –by “we” I mean “Hidden” and Budojapan but we weren’t alone: for the last decade, when inbound tourism started to really take off in Japan, municipal and prefectural and even state bodies and organizations have begun exploring how visitors who come to Japan with an interest in the martial arts could get the most fulfilling experience and how people who know little or nothing about these arts could get introduced to them and appreciate their cultural extensions.

Budo Tourism Guidebook

Covid put a stop in all tourism activities the last three years but that gave some of us the opportunity to regroup and do some homework so we could be better prepared for when the borders opened again. Part of this effort was BAB’s special edition titled “Budo Tourism Guidebook” (as of this writing, available in Japanese only) which also contains the findings of a survey we run online from May 2 to May 31, 2022 as well as a panel we did featuring three non-Japanese who have been living and practicing budo in Japan for many years.

American Embassy Judo Dojo 3

American Embassy Judo Dojo 2

American Embassy Judo Dojo 1

The article you are reading is a summary of that discussion featuring Messrs Lance Gatling from the US, Sandro Furzi from Italy and Michael Reinhardt from Germany. Mr. Gatling has been living in Japan since 1986, he is practicing judo and jiu jitsu and he is the head of the American Embassy Judo Dojo (where this discussion also took place), Mr. Furzi has been living in Japan since 2011 and is practicing Tennen Rishin-ryu kenjutsu, kendo and Brazilian jiu jitsu and Mr. Reinhardt has been living in Japan since 2013 and is practicing Tenshinsho-den Katori Shinto-ryu and Chikubushima-ryu bojutsu. The reason we chose the particular three gentlemen was because it was an opportunity to revisit a previous panel with them from 2014, regarding Japan’s budo as seen through the eyes of non-Japanese –to tie things together, that discussion can also be found in the “Budo Tourism Guidebook”.

Sandro Furzi (Tennen Rishin-ryu kenjutsu)

Lance Gatling (judo and jiu jitsu)

Michael Reinhardt (Tenshinsho-den Katori Shinto-ryu and Chikubushima-ryu bojutsu)

The discussion this time started with Covid and how it affected the practices of the three panelists. Mr. Reinhardt and Mr. Furzi remarked that their practice was of course disrupted and that members of their schools from abroad couldn’t visit but when the measures ended and practice resumed, things returned to normal and with more people coming in. According to Mr. Gatling (who as the host was also acting as a moderator in this panel) things were much worse for his practice since, because of the nature of judo, there was no safe way to practice so they basically had to close the dojo down and wait for the Covid storm to pass.

Attempts at budo tourism

Hayasizaki Iai Shrine

Using Covid as pivot, the conversation moved to companies that just before the pandemic had started offering budo tourism packages; Mr. Gatling mentioned two of these efforts, one by the website Japan Budo Experience that has Japan divided in areas and has been affiliated with small dojo or groups in each area offering budo experience to tourists and the other, Alex Bradshaw’s Samurai of Culture which promotes the tradition he practices, Jigen-ryu as well as the broader Kagoshima culture within which Jigen-ryu exists. Mr. Gatling pointed out there that these efforts are private and that the Japanese government hasn’t been involved in the promotion of budo as point of focus for tourism although it was supposed to be part of the “Cool Japan” initiative. Here, Mr. Reinhardt, brought up an initiative by Yamagata Prefecture offering a budo experience revolving around iaido since the prefecture is considered the birthplace of the art; the initiative involved a visit to the Hayasizaki Iai Shrine and to a nearby dojo for an introduction to the art.

Alex Bradshaw’s Samurai of Culture (Jigen-ryu)

Japanese Sword Museum, Tokyo

Especially regarding judo, Mr. Gatling added that the Tokyo Judo Federation is also taking some actions to network with practitioners from abroad; the All-Japan Judo Federation does that at a higher, professional level but the Tokyo organization is aiming at a more amateur/sportsman level. Still, and to the extent of his knowledge, there is yet no government strategy towards promoting budo. Here, Mr. Reinhardt mentioned that he is aware of a discussion regarding the creation of a budo museum and suggested that an already existing facility e.g. the Japanese Sword Museum in Tokyo could become a hub for information and activities related to Japan’s warrior culture starting from the Kamakura period and which could also include budo. To that Mr. Gatling commented that since visitors are interested in seeing and experiencing budo, but because any major action to support that interest would take considerable resources, perhaps some organization (like “Hiden” even!) could organize a round table where the major budo organizations like the All-Japan Kendo Federation, the All-Japan Judo Federation and the koryu associations could discuss how to address this matter.

Budo tourism: challenges

At this point, Mr. Gatling asked the other two gentlemen what would the challenges to support budo tourism be in their particular arts. Mr. Furzi was first to respond by stressing one main problem for tourists: their limited time in Japan and how it conflicts with the way koryu are organized here i.e. non-professional instructors only teaching once a week. Considering tourists have at best a month in their disposal and that they also want to do other things, they rarely have the opportunity to practice more than a couple of times with an instructor they might be admiring from afar. Mr. Gatlling confirmed that from his experience, coordinating the itineraries of tourists with the schedule of Japanese dojo can be a serious problem, especially for tourists who want to practice every day and also pointed out that more often than not, travel insurance doesn’t cover budo practice and particularly judo which is considered a dangerous activity.

At this point, Mr. Gatling asked the other two gentlemen what would the challenges to support budo tourism be in their particular arts. Mr. Furzi was first to respond by stressing one main problem for tourists: their limited time in Japan and how it conflicts with the way koryu are organized here i.e. non-professional instructors only teaching once a week. Considering tourists have at best a month in their disposal and that they also want to do other things, they rarely have the opportunity to practice more than a couple of times with an instructor they might be admiring from afar. Mr. Gatlling confirmed that from his experience, coordinating the itineraries of tourists with the schedule of Japanese dojo can be a serious problem, especially for tourists who want to practice every day and also pointed out that more often than not, travel insurance doesn’t cover budo practice and particularly judo which is considered a dangerous activity.

Mr. Reinhardt and Mr. Furzi’s experience in that area was somewhat different since tourists who visit their kenjutsu schools are mostly people with some experience in their particular art or budo in general so they know how to behave in a dojo and in handling a sword; furthermore, since koryu arts are mostly kata-oriented and beginners need to learn how to do basic sword cuts and basic movements, the material taught to tourists isn’t conducive to accidents. They also remarked that for most tourists, just being in Japan and being able to train in a Japanese dojo with a Japanese teacher with 50 years of experience, is rewarding and allows them a connection deep enough to satisfy their needs.

Mr. Reinhardt and Mr. Furzi’s experience in that area was somewhat different since tourists who visit their kenjutsu schools are mostly people with some experience in their particular art or budo in general so they know how to behave in a dojo and in handling a sword; furthermore, since koryu arts are mostly kata-oriented and beginners need to learn how to do basic sword cuts and basic movements, the material taught to tourists isn’t conducive to accidents. They also remarked that for most tourists, just being in Japan and being able to train in a Japanese dojo with a Japanese teacher with 50 years of experience, is rewarding and allows them a connection deep enough to satisfy their needs.

Here, the matter of visas for cultural activities came up: Mr. Gatling mentioned that his dojo often gets requests from visitors who want it to sponsor them for a long-term visa so they can study budo. Mr. Furzi confirmed that this is how he first came to Japan and that his late teacher wrote him a letter of recommendation so he could get a “cultural activities visa” which includes activities like ikebana and budo while Mr. Reinhardt added that he too came with a one-year “working holiday visa” that allowed him to live and work in Japan and at the same time practice martial arts.

Here, the matter of visas for cultural activities came up: Mr. Gatling mentioned that his dojo often gets requests from visitors who want it to sponsor them for a long-term visa so they can study budo. Mr. Furzi confirmed that this is how he first came to Japan and that his late teacher wrote him a letter of recommendation so he could get a “cultural activities visa” which includes activities like ikebana and budo while Mr. Reinhardt added that he too came with a one-year “working holiday visa” that allowed him to live and work in Japan and at the same time practice martial arts.

Adding to time, money and visas, another problem for experiencing budo in Japan as a tourist was, according to the three panelists, language. To that, Mr. Reinhardt pointed out that even though his dojo has been having foreign visitors for decades, most people don’t speak English so some level of Japanese is necessary; having that will also help in everyday life and also, in the long run, allow the practitioner to communicate better with their instructor and reach a deeper level of understanding.

Recommended spots (and information sources) for budo tourists

The site of Shinto Munen-ryu’s Renpeikan dojo

The next question posed by Mr. Gatling, was what would be some recommended spots for martial artists who visit Japan. Mr. Furzi’s reply was that Japan (and even Tokyo) is filled with spots of interest for martial artists if you know how to look for them; as an example he mentioned the site of Shinto Munen-ryu’s Renpeikan dojo, one of the three major kenjutsu dojo of Edo, right in the precincts of Yasukuni Shrine. Mr. Reinhardt’s response was that the spots would of course vary depending on the budo the visitor is interested in –in his case, since his interest focuses on the schools he practices, he takes visitors to Katori and Kashima shrines, explains their connection to Katori Shinto-ryu and Kashima Sninto-ryu and shows them the graves of the founders of the two arts and on his way back also visits the grave of Ono-ha Itto-ryu founder near the Narita-san temple.

Kashima Shrine, Ibaraki prefecture

Katori Shrine, Chiba prefecture

For Mr. Reinhardt, Japan has many spots like that but due to lack of information in English, they aren’t always accessible to tourists. Especially if these spots are in the countryside, transportation to them might not be easy, local people are even less likely to be able to communicate in English and sometimes, small dojo or other facilities aren’t open and some contact must be made in advance so someone will be there to open them for visitors –all these are possible obstacles for the potential foreign visitor making the presence of a guide necessary.

Nen-ryu dojo in Maniwa city, Gunma Prefecture.

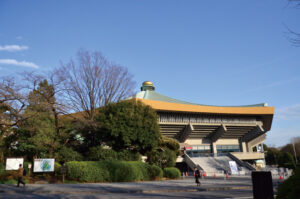

Here Mr. Gatling, using Mr. Reinhardt’s research on Japan’s old dojo which has led him to visit about 25 of them all over the country, brought the conversation to the subject of such facilities being important for the development of tourism in various areas of the country and expressed his concern that very often local authorities don’t realize how budo can be an area’s touristic attraction. Good examples of that are, he continued, the city of Iga in Mie Prefecture and the way it has been promoting the ninja phenomenon as well as the Kodokan with its museum and training halls, as main points of interest for judo fans; on the opposite end of the spectrum, he cited even big budo organizations like the All-Japan Kendo Federation that do not have a central training facility or a museum they could use as a point of interest for tourists. For Mr. Gatling, such spots, at least in Tokyo could include the Japanese Sword Museum, the Sumo Museum in the Ryogoku Kokugikan arena and the Nippon Budokan and its Budo Gakuen school.

Ninja museum in the city of Iga

Kodokan, Tokyo

Nippon Budokan, Tokyo

As an aside to the above, the discussion turned to reading material that might help visitors to Japan prepare for their trip in regards to budo culture. The names mentioned by the three panelists were Donn Draeger, Ellis Amdur, Alex Bennett, Nakajima Tetsuya, Jigoro Kano and Eric Shahan and his translations of Meiji period budo books, but there was also a special mention of our articles here in “Hiden” and Budojapan, and especially my “Koryu Experience” and the “Worldwide Koryu Dojo Report” series; I hope the reader wouldn’t mind if I took the opportunity to thank our guests for their kind words regarding our work!

The 5th Higashi Nihon Kobudo Enbu Taikai in Konpira shrine, Tokyo

The next point Mr. Gatling made was the lack of a “central clearing house for budo activities”; in other words a place where someone could go and find information about budo-related activities happening on any given moment. Mr. Gatling did mention the section about budo events on the “Hidden” website but argued that it should be bigger and contain many more events and that there could be some business model that would allow such a portal to be as comprehensive as possible and also be self-sufficient. He also said that he was always puzzled by the fact that the Nippon Budokan didn’t have a central information channel for budo events held in it and that interested parties should have to go to other organizations’ websites to find out about them.

How dojo handle budo tourists

Chikubushima-ryu bojutsu (Michael Reinhardt and Matsuura Toshihide)

Returning to interaction between dojo and visitors, the next question was: what happens when visitors to a dojo have no previous experience of the art taught there or even of budo in general? Mr. Reinhardt repeated that his Katori Shinto-ryu dojo has only had visitors who are already familiar with the school but added that from time to time it holds introductory classes for potential members; these are two-hour classes held in weekdays, separate from regular practice but participants are almost exclusively Japanese. He also spoke highly of an experience he had when he first came to Japan was with the Kamakura-based branch of the Nagoya Shunpukan; that dojo, for a symbolic fee, would assign to visitors who wanted to experience their arts (Yagyu Shinkage-ryu kenjutsu and Owarikan-ryu sojutsu) one or two advanced students who would stay with them for a whole session.

Kato Kyoji showing the technique of Ten-chi-jin, Tennen rishin-ryu to the author

Gekiken Shiai, grappling on the ground, Sandro Furzi

Mr. Gatling added here that one problem judo has for first-time visitors is that it presupposes knowledge of falls: unless someone knows how to fall safely (which takes time and isn’t always pleasant!) they can’t really experience judo and then turned to Mr. Furzi who had a rather unexpected experience to contribute: in his school, Japanese visitors tend to be more casual and sometimes might join for a while and then leave, whereas non-Japanese tend to be much more focused, have researched the school and immediately want to join. His explanation for this is that, unlike the Japanese who know they are always near the school and they can join whenever they want, non-Japanese have limited time in Japan so they try to make the most of it. He also added that his teacher asks visitors to practice three-four times before joining.

Scottish judo teachers visit to Tokyo May 2023, American Embassy Judo Dojo.

Visitors’ expectations

Sandro Furzi experiencing Katori Shinto-ryu.

The conversation next turned into whether people have different expectations from their budo experience depending on the culture they come from i.e. Europe, the US etc. Mr. Furzi’s reply was that he hasn’t seen much difference in terms of nationality but what he has seen is that visitors share an interest in Japan’s culture and history. Mr. Reinhardt on the other hand said that he has seen some level of unfulfilled expectations especially from visitors who are already advanced practitioners or even instructors in their country but find themselves being again students in the school’s dojo in Japan. Both Mr. Furzi and Mr. Reinhardt agreed that perhaps in the case of Katori Shinto-ryu, because of its popularity, people have already some preconception about how it “should” look and the same might be true with Mr. Furzi’s Tennen Rishin-ryu and its connection to the Shinsengumi.

Michael Reinhardt experiencing Tennen Rishin-ryu.

Still on the subject of expectations, Mr. Furzi and Mr. Reinhardt said that visitors to their dojo always have the opportunity to practice with the top instructors, because their dojo are small and because their teachers are very hands-on. Regarding visitors’ reluctance to practice basic exercises and techniques (something that often happens with non-Japanese) both gentlemen said that they haven’t experienced anything like that because visitors are usually just happy to be there and be able to practice with Japanese teachers in a Japanese environment and because in their schools, basics are a big part of practice and everyone does it regardless of their level. As for Mr. Gatling since his dojo mainly caters to diplomats or visitors with limited time in Japan and not necessarily with some special interest in judo, he has come across some who had a difficulty compromising with the Japanese way of teaching (insistence on basics etc.). However because the dojo has several instructors, they can split practice in groups where different people practice different things at the same time.

Lance Gatling explaining to Sandro Furzi the judo’s kuzushi principle.

One last word

In closing, Mr. Reinhardt pointed out that since Japan’s tourism situation is changing with more and more people visiting from abroad, perhaps those involved with budo (and especially outside the big cities) should get more active because that could mean an increase of interest for their regions. Mr. Furzi added that all budo practitioners should try to come to Japan and experience practice here –even if it isn’t what they had pictured it in their head, if they are patient and give it time, they will certainly benefit from it and enjoy it!

Overall, several interesting points came up, points that could and should be included in any discussion about the creation of a strategy regarding budo tourism. Our panelists are only three of the non-Japanese who are involved in Japan’s martial arts’ scene; there are several more who can also contribute ideas, points of view and proposals that could help Japan make the most out of this important part of its culture. Oh, and incidentally all three participants are also involved in research projects that will also help raise more awareness on budo worldwide: Mr. Gatling on judo’s Jigoro Kano, Mr. Reinhardt on Katori Shinto-ryu and on dojo buildings around Japan and Mr. Furzi on gekiken, the predecessor of kendo as practiced in the Edo period. And yes, we will be presenting their work in the near future!

Grigoris Miliaresis

About the writer

Grigoris Miliaresis has been practicing Japanese martial arts since 1986. He has dan grades in judo, aikido and iaido and has translated in Greek over 30 martial arts’ books including Jigoro Kano’s “Kodokan Judo”, Yagyu Munenori’s “The Life-Giving Sword”, Miyamoto Musashi’s “Book of Five Rings”, Takuan Shoho’s “The Unfettered Mind” and Donn Draeger’s “Martial Arts and Ways of Japan” trilogy. Since 2007 his practice has been exclusively in classic schools: Tenshin Buko-ryu Heiho under Ellis Amdur in Greece and Kent Sorensen in Japan and, since 2016, Ono-ha Itto-ryu under 17th headmaster Sasamori Takemi and 18th headmaster Yabuki Yuji.