Battling the samurai myths: An interview with historian Karl Friday

Interview and Text by Grigoris Miliaresis

Dr. Karl Friday’s lecture at Cambridge University

Everyone knows you cannot throw an opponent unless you have broken their balance. And everyone knows when you are facing someone with a long weapon while armed with a shorter one, you must enter their space to render theirs useless. And everyone knows you cut generating power from the hips -we’ve verified practically all these so many times during practice that we believe them concretely. At the same time, everyone knows samurai were following the code of bushido and everyone knows that koryu arts were developed for the Sengoku Period (1467-1615) battlefields and everyone knows that it was after the Meiji Restoration of 1868 that “jutsu” arts became “do” arts but the certainty with which we believe these (and many more) isn’t equally well-founded: we believe them because they are “common knowledge”, often repeated by the venerable teachers who have spent decades practicing the arts they are bequeathing to us.

As everyone who has read Japanese history actually knows, many of these things aren’t true; for the most part our ideas about our ancestors in Japan’s classical arts have been shaped by information coming from sources that historians view with, mildly put, skepticism. From the medieval war tales like Heiji Monogatari and Heike Monogatari, to Bunraku and Kabuki plays like Chushingura or Ichi-no-Tani Futaba Gunki, to TV and cinema dramas ranging from the depths of Akira Kurosawa to the superficiality of Mito Komon, art has been providing us both the images and the ideas we project on Japan’s warriors, their fighting methods and the thinking that shaped them. And while not everyone among us is or is willing to be a historian, we should occasionally have an honest discussion with them about which of our beliefs are actually facts and which are fiction; this might not change the way we practice but it can certainly change the way we think about our practice!

Dr. Karl Friday, professor emeritus of Japanese history of the Universities of Georgia in the US and Saitama in Japan, specializing in medieval military history and author of Hired Swords: The Rise of Private Warrior Power in Early Japan (1992), Legacies of the Sword: the Kashima-Shinryu & Samurai Martial Culture (1997), Samurai, Warfare & the State in Early Medieval Japan (2004) and The First Samurai: the Life & Legend of the Warrior Rebel, Taira Masakado (2008) is in a unique position to participate in such a discussion. Not only because of his academic background but also because he is extensively involved with the martial arts reaching menkyo kaiden license in Kashima Shinryu after studying for many years under shihanke Seki Fumitake. Dr. Friday was kind enough to address some of our basic preconceptions about koryu arts and the samurai and I believe his answers will help many of us put some things in order -after an initial kuzushi!

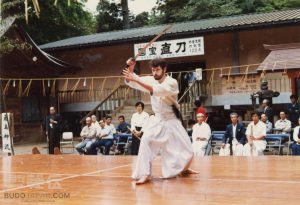

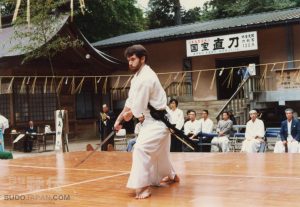

Kashima Shinryu battojutsu by Dr. Karl Friday at Kashima Shrine

An interview with historian Karl Friday

Samurai: different periods, different roles

–Let’s start with samurai: we use this word as a blanket term but forget this is a class spanning almost eight centuries, correct?

Kashima Shinryu battojutsu at Kashima Shrine

Yes. The term “samurai” has many different meanings in Japanese, depending on the period, and it didn’t always refer to warriors. It has also become an English word for “Japanese warriors.” But more important than terminology per se is the fact that warriors and their role in society changed pretty dramatically over the course of the ten or so centuries between the middle of the Heian period, when private warriors first came to monopolize military force to when the samurai were abolished as a class, during the Meiji period.

–And both warfare and the samurai position in society changed from period to period…

Yes, both changed a lot over time. During the Heian period, they were tax collectors, deputized law enforcement officers, and body guards or other military servants to court nobles. From the late twelfth century, after the creation of the first shogunate, they gradually usurped political and economic control over the countryside. And by the fifteenth century, they were effectively ruling the country—although the emperor and his court in Kyoto were never fully displaced. Similarly, the military technology that created and defined the warrior order was mounted archery, practiced by warriors fighting in very small squads. By the late eleventh century, fortifications began to play larger roles in the fighting, but battles still centered on mounted archers. Archers on foot, augmented by spearmen on foot, became prominent from the late fifteenth century, and from the late sixteenth century gunners began to displace archers.

Samurai battle during the Muromachi Period

–So koryu aren’t battlefield arts after all?

Kashima Shinryu Bojutsu at Kashima Shrine

It doesn’t appear so. There are several things pointing to this conclusion. First, bugei ryuha only began to appear in the 1400s, which is exactly the point at which the value of individual skill was fading, as battles focused more and more on well-disciplined units of soldiers. In other words, ryuha bugei, which focused on developing prowess in personal combat, emerged and flourished in almost inverse proportion to the value of skilled individual fighters on the battlefield. Second, koryu training centers heavily on swordsmanship, while swords were never a primary battlefield weapon. And third, the limited numbers of ryuha active in the medieval period indicate that there couldn’t have been more than a few thousand people training in this way at any given time, while sixteenth-century armies often numbered in the tens of thousands.

This strongly suggests that ryuha bugei was never about direct training for the battlefield; it was always about something else—something more. That is, ryuha bugei aimed from the start at conveying more abstract ideals of self-development and enlightenment, something related to, but not synonymous with, military training per se. Ryuha bugei was an abstraction of military science, not merely an application of it. It fostered character traits and tactical acumen that made those who practiced it better warriors, but its goals and ideals were more akin to those of liberal education than vocational training.

Chivalrous, one-on-one duels and the sword as a symbol

—Is there anything we can say with certainty about how samurai actually fought in the medieval —battlefields -and how they practiced to do that?

“Certainty” is always an elusive goal in historical study—which is, of course, always a reconstruction of the past through surviving evidence. The kinds of sources that historians usually deem most reliable—letters, diaries, legal records, and the like—tend to be maddeningly laconic in their descriptions of battles for most of the classical and medieval ages. So we need to reconstruct battlefields from more indirect evidence, such as casualty reports, archaeological and other physical evidence, careful analysis of literary texts, pictorial sources and the like. Even so, historians have reconstructed quite a bit, especially over the past three decades or so.

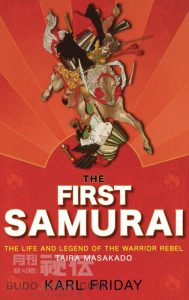

Traditional images of bushi warfare were based mainly on fairly uncritical use of literary accounts—particularly medieval war tales (gunki) like Heike monogatari and Taiheiki for earlier periods and accounts like Koyo gunkan and Shincho koki for later periods—and fanciful artwork like the famous screen paintings of battles such as Kawanakajima kassen zu byobu and Nagashino kassen zu byobu. Literary and artistic sources are full of distortions introduced by the entertainment or didactic purposes for which they were produced, and by problems of anachronism and implausibility introduced by the authors’–writing decades or even centuries after the fact—lack of familiarity with real battlefields. As early as the 1960s, literary scholars had begun to question the historical reliability of these chronicles, demonstrating that much of the compelling detail that made these sources seem plausible was clearly manufactured in the artists’ imaginations. Perceptions were also distorted by the effect of nearly three centuries of peace during the Tokugawa period, and by modern political agendas during the Meiji, Taisho and early Showa eras.

The Battle of Kawanakajima (Katsukawa Shuntei, 1845)

Beginning around the early 1990s, though, there has been an outpouring of new research based on close analysis of a diverse mixture of sources and evidence and cross comparison with work on military technology and tactics in other times and places. This new work overturns many of the stereotypes that dominated previous treatments of the subject.

Kashima Shinryu kenjutsu at Kashima Shrine

The points likely to be of the most interest to Hiden readers include rejection of the old idea that early samurai warfare centered on chivalrous one-on-one duels between warriors who selected appropriate opponents through ritualized recitations of pedigrees and achievements—an image that came mostly from Heike monogatari—and a reassessment of the role of hand-to-hand combat with bladed weapons during both the early and late medieval epochs. Closer analysis of a better range of sources has shown that Heian battles were every bit as brutal as those of the Sengoku era. Tactical planning centered on attempts to catch opponents off guard, in ambushes or surprise attacks, particularly night attacks on the enemy’s home.

Similarly, popular images of sixteenth-century warfare, reinforced by decades of samurai movies, envision pitched battles fought on open plains, across which opposing sides form up and then charge in ranks of cavalry and infantry units, closing and battering one another with swords and other close-range weapons. But most historians now agree that this image was largely manufactured for political propaganda purposes during the Meiji era. Careful analysis of casualty reports, pictorial records, and archaeological data reveals that Japanese tactical thinking was dominated by missile weapons—bows, slings, and later firearms—throughout the premodern period.

—Where does the sword enter in all this? Because even if we bypass the “soul of the samurai” mythology, it is the most prominent weapon in the world of koryu.

Kashima Shinryu battojutsu at Kashima Shrine

Swords had a singular status as symbols of power, war, military skill and warrior identity. As emblems of power, they appear in the earliest Japanese mythology, and were regularly presented by medieval warrior leaders as gifts or rewards to their followers. By the fourteenth century, expressions like “clash of swords” (tachi uchi, katana uchi, or uchi tachi), or “wield a sword” (tachi tsukamatsurare) were recognized as generic appellations for combat, irrespective of the actual weapons employed. I think that the special place of swordsmanship in koryu curricula comes from the fact that it represented a symbolic sine qua non of personal combat: a kind of michi within a michi for bugeisha, then as now. This representational function is reflected in the popularization of the term “hyoho” (or “heiho”)—which, until late medieval times, designated military science or martial art in the broad sense—as a synonym for kenjutsu.

Popular audiences—and even earlier generations of scholars—have tended to confound the symbolic importance of the sword to early modern samurai identity with prominence in medieval battles. But the newer research has made it clear that swords were used far more often in street fights, robberies, assassinations and other (off-battlefield) civil disturbances than on the battlefield. It’s true that most of the troops that made up both early and later medieval armies carried swords, but they were never a key battlefield weapon; they were always supplementary weapons, analogous to the sidearms worn by modern soldiers.

As for “Bushido”

—The other thing that seems to be part of every discussion about samurai is their moral code, usually identified with the word “bushido”. Modern academics including you, Dr. Alex Bennet, Dr. Oleg Benesch, and the late Dr. G. Cameron Hurst, III have all put bushido and the philosophy allegedly behind it on more solid historical foundations. Could you say a few words about this?

“Bushido” is a very tricky term. It was scarcely used at all until the modern period, but even as a kind of historiographic term–i.e. a modern label for warrior ideology—it’s a problematic construct. For one thing, there was very little discussion in written form of proper “warrior-ness,” before the Tokugawa period. The concept of a code of conduct for the samurai was a product of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, when Japan was at peace, not the medieval “Age of the Country at War.” The samurai of this period were bureaucrats and administrators, not fighting men; the motivation held in common by all those who wrote on the “way of the warrior” was a search for the proper role of a warrior class in a world without war. The ideas that developed out of this search owed very little to the behavioral norms of the warriors of earlier times.

Kashima Shinryu battojutsu at Kashima Shrine

The real problem, though, was that while there was lots of debate, there was little or no agreement. I tell my students that “bushido” belongs to the same class of words as terms like “patriotism,” or “masculinity” or “femininity.” That is, everyone pretty much agrees that these are good qualities to possess, but few agree on what they actually involve: Are Edward Snowden or Geert Wilders patriots? Is Angela Merkel more or less feminine than Marilyn Monroe? The same issues plagued the Tokugawa (and modern) participants in the debate on proper warrior values and behavior. An illuminating example of how diverse opinion really was can be found in the debate over the actions of the famous 47 ronin of Ako (memorialized in the story “Chushingura”).

In the modern era, the Japanese government and the Imperial Army and Navy pushed the notion of “bushido” as a way to foster the sort of military spirit they desired from their soldiers and sailors. But no, the code they preached did not have much to do with anything the samurai believed in or practiced. The connection between Japan’s modern and premodern military traditions is thin–it is certainly nowhere near as strong or direct as government propagandists, militarists, Imperial Army officers, and some post-war historians have wished to believe.

—Which leads us to the question “where popular understanding of samurai comes from?”

Mostly, I think, from movies, TV shows, and books and websites by aficionados who aren’t conversant with what academic historians have discovered in recent decades. Authors of popular treatments of samurai history often do consult academic works, but they tend to cherry-pick both the studies and the information in them, fitting it into a framework that conforms to their preconceptions.

—You are the only historian who is also a high-level koryu practitioner. I assume your knowledge of history has informed your practice -has this also worked the other way round?

I’m not the only one, even if you limit “historian” to professional academics! But that aside, yes, I do find that hands-on experience with weapons training helps a lot when I’m trying to analyze sources and visualize—reconstruct—what’s being described.

Kashima Shinryu battojutsu at Kashima Shrine

—Do we all need this level of knowledge to become better practitioners? If not, could you suggest a few resources that will at least take us a little further?

On warfare, and general warrior history, I’d start with Kawai Yasushi’s article on the history of research on these topics, “Medieval Warriors & Warfare,” in The Routledge Handbook of Premodern Japanese History,(Routledge, 2017); and with Thomas Conlan’s and my chapters (“Japan 1200-1550” and “Japan to 1200”) in The Cambridge History of War, vol 2: War in the Medieval World (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020), which give good summaries of the current views of professional historians, and also offer good bibliographies for further reading.

On bugei history, I’d recommend starting with my “Off the Warpath: Military Science & Budo in the Evolution of Ryuha Bugei,” and the other articles in Alexander Bennett’s Budo Perspectives (Auckland, NZ: Kendo World Publications, Ltd, 2005), especially William Bodiford’s “Zen and Japanese Swordsmanship Reconsidered”; Bodiford’s essays in essays in Martial Arts of the World: An Encyclopedia (ABC-Clio Publishing, 2001); and Denis Gainty’s Martial Arts and the Body Politic in Meiji Japan (Routledge, 2015).

On bushido, the definitive work is Oleg Benesch’s Inventing the Way of the Samurai: Nationalism, Internationalism, and Bushido in Modern Japan (Oxford University Press, 2016). My most recent statements on this subject—focusing on early medieval warrior values—are “Samurai and Bushido in Premodern Japan,” in Oxford Handbook of Warfare in Asia (Oxford University Press, 2021); “The Way of Which Warriors? Bushido & the Samurai in Historical Perspective, in Azijske Studije 6.2 (2017); and my Samurai, Warfare, and the State in Early Medieval Japan (Routledge, 2004).

Grigoris Miliaresis

About the interviewer

Grigoris Miliaresis has been practicing Japanese martial arts since 1986. He has dan grades in judo, aikido and iaido and has translated in Greek over 30 martial arts’ books including Jigoro Kano’s “Kodokan Judo”, Yagyu Munenori’s “The Life-Giving Sword”, Miyamoto Musashi’s “Book of Five Rings”, Takuan Shoho’s “The Unfettered Mind” and Donn Draeger’s “Martial Arts and Ways of Japan” trilogy. Since 2007 his practice has been exclusively in classic schools: Tenshin Buko-ryu Heiho under Ellis Amdur in Greece and Kent Sorensen in Japan and, since 2016, Ono-ha Itto-ryu under 17th headmaster Sasamori Takemi and 18th headmaster Yabuki Yuji.

http://about.me/grigorismiliaresis