Beyond Nikko and Strawberries: Tochigi Prefecture Budo Tourism Trial Tour

Text by Grigoris Miliaresis

Before sushi and tempura, before manga and anime, before Super Mario and Pokemon, the cultural artifact that drew people from all over the world to Japan was the martial arts –those over 50 probably remember vividly the time when karate and judo and not cars, cameras or electronics where Japan’s main exports. And even today, augmented by kendo, aikido and samurai and ninja as portrayed in the entertainment industry, Japan’s martial culture is still a big part of its soft power, even attracting non-practitioners. At the same time, inbound tourism is at an all-time peak so it makes perfect sense that both the national and local governments would start examining how to integrate martial arts in their existing tourism policies or even use them to spearhead some brand new ones.

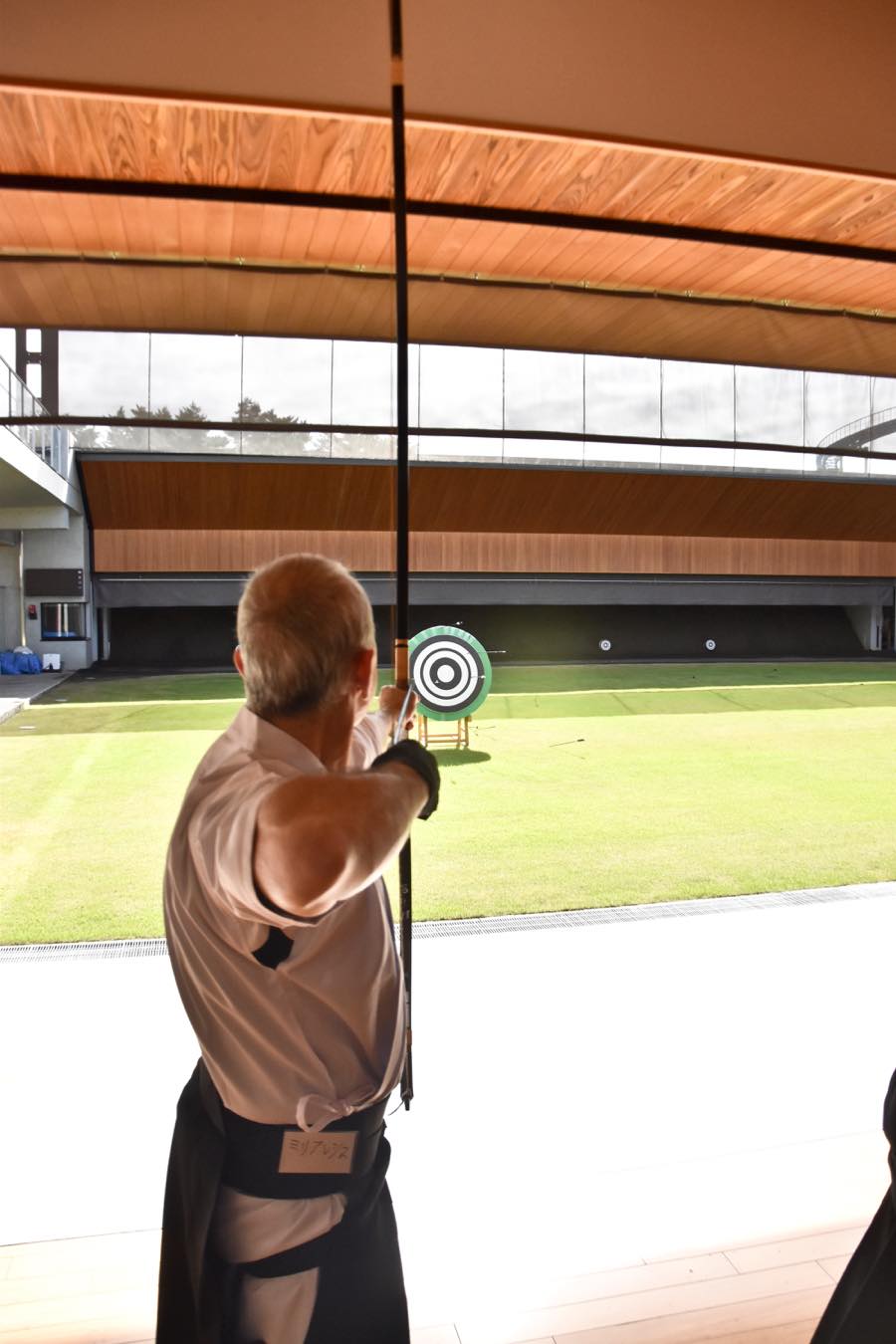

Shooting demonstration by the Tochigi Kyudo Federation instructors

“Hidden” and Budojapan have been following these initiatives, collectively called “Budo Tourism” for a while; our “Budo tourism: what do the budoka think?”, Alex Bradshaw’s article on Satsuma’s Jigen-ryu, our coverage of the tour of Aomori’s martial traditions or the 2023 “Budo Tourism Guidebook” are among our efforts to support this idea and help the promotion of such actions all over Japan. So it was with great pleasure that we accepted the invitation of the Tochigi Prefecture Sports Commission (TPSC) to participate in their Tochigi Prefecture Budo Tourism Trial Tour in October: a three-day program attempting to showcase Tochigi’s historical heritage and its relationship to the martial arts and particularly the oldest and most revered weapon art of Japan’s warriors, kyudo archery.

The project –and the concept

Gathering of participants at Oyama Station, Tochigi

To gather participants for this pilot project, the organizers (TPSC and Nippon Travel Agency/NTA who implemented it) promoted it online and had it open to “foreign residents in Japan who are interested in budo (Japanese martial arts)” with the condition that participants “should be able to post about the tour at least once on social media”. This was obviously an effort to engage the publicity power of Internet influencers and indeed outside my editor Takashi Ogawa and myself, there were only two other traditional media journalists in the group: the other 16 participants were people from various countries including the United States, Australia, Taiwan, Malaysia and India who are living in Japan for times ranging from a couple of years to over a decade and who had never practiced martial arts.

Various types of arrows used in the past

A main issue arising when budo tourism events are planned is incorporating in them local culture elements: if “budo tourism” means just doing a hands-on trial of a martial art in a martial arts’ facility, the “tourism” part is negated: that can be easily done in Tokyo. The Tochigi organizers found a central point, archery (i.e. kyudo) and planned the whole event around it, drawing from the prefecture’s history and particularly the history of two local folk heroes, Fujiwara no Hidesato, a Heian Period aristocrat involved in the suppression of provincial lord Taira no Masakado’s revolt in 940 and Nasu no Yoichi, a bushi known from the “Tale of the Heike”. Since both warriors were known for their prowess in archery (like all bushi until the Muromachi Period), other than visits to locations related to the two, the trial tour also contained a hands-on kyudo experience at the Utsunomiya Yukei Budokan facility as well as a sado and a zazen experience (see sidebars.)

1890 ukiyo-e of Fujiwara no Hidesato by Tsukioka Yoshitoshi

Fujiwara no Hidesato & Nasu no Yoichi

To help participants understand more about Fujiwara no Hidesato, a visit to the Karasawayama Castle ruins near the city of Sano was included. This mountain castle, allegedly built in 927 and used until the Sengoku Period, was one of the Seven Famous Castles of Kanto Region and its lords where members of the House of Sano claiming descent from Hidesato; unfortunately, other than the walls the only thing that can be seen today is a 1883 Shinto shrine enshrining Hidesato.

Visiting Karasawayama Castle ruin

Karasawayama Castle walls

At Karasawayama Shrine

View from the Karasawayama Castle site

In the same vein, in Utsunomiya we also visited Futaarayama shrine, built on a 135-meter hill in the city’s center and with a spectacular 9.7 m/31.8 ft ryobu torii gate. Founded in 353, the shrine was responsible for the creation of the city surrounding it (and for the Utsunomiya name itself) and since one of its enshrined deities, Toyokiirihiko-no-mikoto, the eldest son of mythical Emperor Sujin (97 BC-30 BC) was supposed to be a fierce warrior it was patronized by many bushi from Hidesato and Nasu no Yoichi up to Tokugawa Ieyasu. (According to legend, Hidesato defeated Masakado using a magic sword given to him at this shrine.)

Futaarayama Shrine ryobu torii gate

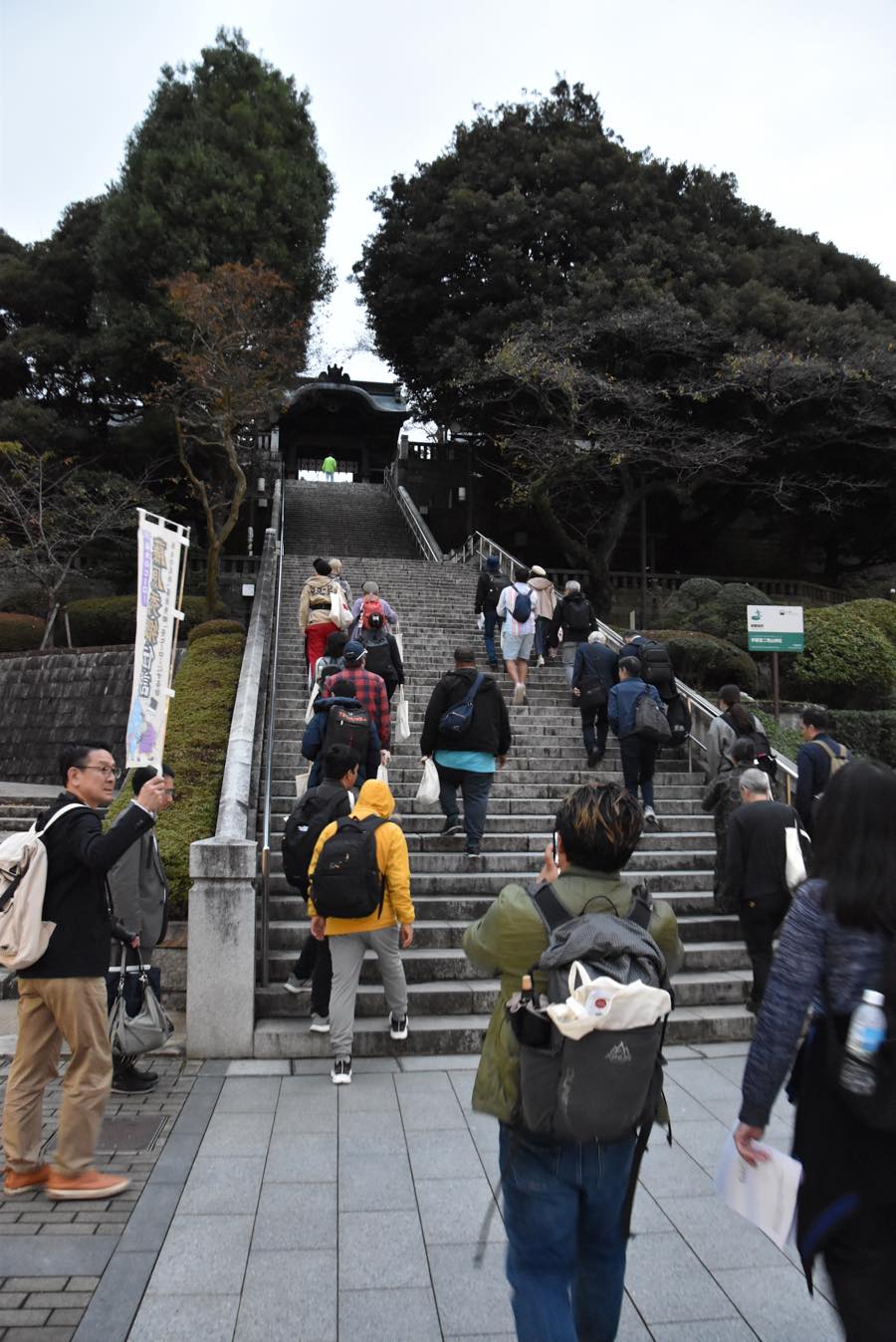

Climbing up the stairs to Futaarayama Shrine

Futaarayama Shrine

Dr. Tetsuo Owada

Between the two shrine visits, the organizers had arranged a lecture at the Tochigi Prefecture Museum from Dr. Tetsuo Owada, a historian and emeritus professor of Shizuoka University, director of the Gifu Sekigahara Battlefield Memorial Museum and author of over 50 books on the Sengoku Period. The lecture was a brief account of Fujiwara no Hidesato and how he changed from a historical figure to a folk hero; the part that was particularly interesting was his view that the “Tawara Toda” tale about Hidesato killing a giant centipede as well as another tale that has him fighting a domeki, a supernatural creature with a hundred eyes, are allegories for him fighting against Taira no Masakado. Another highlight from that lecture was that we were allowed to look from up close, an Edo Period picture scroll of the “Tawara Toda” not regularly on exhibition: the illustrations were amazing!

Tochigi Prefecture Museum lecture

Examining the “Tawara Toda” Edo Period picture scroll

Yoichi-kun, the mascot of Otawara

For the Nasu no Yoichi part of Tochigi bushi history, we visited the Nasu Yoichi Folklore Museum in Otawara City and the adjacent Nasu shrine. The museum’s main attractions are a sword said to belong to Yoichi and designated a National Important Cultural Property and a puppet theater presentation of the famous story from the “Tale of the Heike” where Yoichi, fighting alongside Minamoto no Yositsune in the battle of Yashima, manages to hit a fan that was fixed on a pole on one of the Taira ships; the Taira had put the fan there to taunt the Minamoto warriors and Yoichi managed to hit it with just one arrow although the boat was rocking and he was in the water riding his horse!

Visiting the Nasu Yoichi Folklore Museum in Otawara

Watching the puppet show at Nasu Yoichi Folklore Museum’s Ogi no Mato theater

Oyoroi armor and arrows from the Nasu Yoichi Folklore Museum collection

As for the shrine, also an Important Cultural Property it is said to have been founded during in the 4th century and is enshrining Hachiman, favored by the Kamakura bushi and particularly the Minamoto; the shrine became important for the House of Nasu because it is said that Yoichi prayed there before the battle of Yashima and like its famous counterpart in Kamakura, it hosts mounted archery competitions in its September festival.

Nasu shrine gate

The torii gate of the Nasu shrine

Experiencing budo: kyudo

Utsunomiya city’s Yuukei Budokan

Kyudo experience opening ceremony

But this was a Budo Tourism event so the most important part was the hands-on experience with the budo stringing together all the other activities: kyudo. Readers of my articles in “Hidden”/Budojapan might remember that in 2018, I had written an article about the 3rd World Kyudo Taikai and 4th International Kyudo Seminar held in Tokyo’s Meiji Jingu kyudojo and titled “Shooting for the truth”. There, I had written

I never got more involved [with it] but remained mystified by kyudo’s both meticulous attention to detail and practicality: again, like sado, the kata was important but if it doesn’t reflect in your tea’s quality, (or your shot) then it’s empty, a purely ritualistic choreography devoid of any martial virtue.”;

the following years, my interest in kyudo only increased so I was really looking forward to experience the real thing!

8th dan hanshi Masubuchi Atsuhito

For this experience the Tochigi Kyudo Federation decided, also very wisely, to involve nine instructors headed by 8th dan hanshi Masubuchi Atsuhito and break our group into four five-people sub-groups with two instructors for each, giving everyone the sense they were having a private lesson. What was even wiser though, was that the planners of the event made the strategic choice to focus only on technique and bypass the etiquette side of kyudo. Everyone who has seen kyudo knows that etiquette is as much important to the art as is technique (archery and etiquette school Ogasawara-ryu was instrumental in creating kyudo as practiced by the All-Japan Kyudo Federation/AJKF) and as the instructors themselves pointed out, it takes a regular kyudo student about three months until they get to actually shoot –if they don’t get right the way to enter, walk, position themselves and hold the bow and arrows they aren’t considered ready to!

The team of Tochigi Kyudo Federation instructors

Shaho Hassetsu: Kyudo’s eight-step kata

Japan resident and kyudo practitioner Jessica Gerrity (@jessintokyo) was assisting at the event

In our case, and considering that everyone involved had never practiced kyudo and almost everyone had never practiced any other budo, the instructors jumped directly to the core of kyudo technique, the eight-fold kata called Shaho Hassetsu which consists of ashibumi (footing), dozukuri (forming the torso), yugamae (readying the bow), uchiokoshi (raising the bow), hikiwake (drawing apart), kai (full draw), hanare (release) and zanshin (remaining spirit) –the definitions are by the AJKF itself. For the ashibumi, the instructors explained that it relates to each person’s yazuka (draw length) so we first had to learn how to calculate that using real arrows and holding them in front of the center of our throat and make sure they run across our outstretched arm and extend about 5 cm/2” from our fingertips. The ashibumi must be wide enough to help the arms make a full draw and allow the body to be steady when this happens.

Ashibumi and dozukuri

Yugamae

Learning how to calculate the appropriate arrow length

To help us feel the tension when doing the hikiwake, kai and hanare, the instructors first had us use a gomuyumi, a contraption that looks like a slingshot and is made up of a grip shaped like the bow’s and a rubber tube; one reason to use that is that drawing a bow and letting the string go without an arrow can cause serious damage to the bow and it’s pretty certain that a beginner will do that because of clumsiness or ignorance.

Experiencing the tension in hikiwake and kai

Experiencing the release of tension in hanare

When they felt that we had repeated the movements enough to be allowed to try it with a bow, they let us borrow one, explaining that we should pick one we felt we could draw with reasonable effort (the one I chose was 11 kg/25 lbs) and had us go a second round of the first steps of Shaho Hassetsu, up to kai i.e. full draw –then we had to slowly return the tsuru (string) to its resting place.

Practicing subiki (drawing the bow without an arrow)

Shooting –and some thoughts

Enteki target

The next step was to actually shoot some arrows. But before going for the real 36 cm/14.2”-diameter kasumi mato three-ring targets set at the kinteki (short) distance of 28 meters/91.9 ft, they set for us the targets used for enteki (long-distance shooting) which have a diameter of 100 cm/39.4” and at a distance of about 10 meters/33 ft. That way, if we followed their instructions, we could actually hit the target and pretty much all of us did –some even managed to hit it near the center! Not that that helped very much of course: when we moved from the big targets to the smaller and the long distance i.e. when things got real, only one of the dozens of arrows fired by all of us managed to hit a target and I am pretty sure that happened by accident!

Wearing the kyudo practice clothes

Part of the organizers’ well-thought-out kyudo experience plan was to allow for it to last four hours; if this sounds too long, it’s good to keep in mind that just the dressing and undressing of 20 non-budoka who had never worn traditional Japanese clothes in their life took a considerable amount of time. After getting dressed we got to watch a shooting demonstration by the instructors in both the kinteki and the enteki targets and there still was enough time for every participant to shoot at least twenty arrows and get some level of familiarization with the process. Of course no one is saying that those four hours were enough to “learn” kyudo but it was certainly enough to get a decent taste of it and realize some of the many difficulties involved in studying the art.

Demonstration by the instructors at the enteki target

Personally speaking this was one of the best budo experiences I’ve had, especially as a beginner. Despite my concerns, it was much more accessible and that was as much owed to the art itself as it was to the instruction of Kasakura Sachiko sensei and Kikuchi Chikanori sensei who were responsible for my sub-group.

Kasakura Sachiko sensei

Kikuchi Chikanori sensei

Back in 2018, in that kyudo story, I wrote that

kyudo is an art that can try even the most disciplined practitioner, demanding accuracy in all levels –literally and metaphorically. But at the same time, it seems to me extremely rewarding, especially when perfect form meets perfect hit creating the perfect shot that can never be repeated; if there is a better metaphor for living, I can’t think of one!”

Having had this experience I can now say with certainty that my initial impression was correct and that it is indeed one of the most fulfilling experiences one can have and perhaps the main reason is that it doesn’t allow any room for pretense or ambivalence: it is you, the bow, the arrow and the target and if you hit it you hit it and if you don’t hit it you don’t and that’s it and that’s how it has always been from the battlefields of the Kamakura bushi until today. It is budo in its most bare, unadorned form and as such it is at the same time extremely fun and extremely deep.

Group picture with the Tochigi Kyudo Federation instructors at the end of the event

Sado

Sado utensils at the Keiunkyo chasitsu (tea room) in the Kikusuien Garden

Since its beginning in Japan which is attributed to founder of Zen Buddhism’s Rinzai sect Eisai who was very close to the Kamakura shogunate, sado or “tea ceremony” as it is been somewhat erroneously known in the West, has been following samurai culture almost in lockstep. The Ashikaga shoguns supported sado even more and the art reached its apogee through the work of Sen no Rikyu, tea master for warlords Oda Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi. This unique performance art based on the appreciation of tea itself, the equipment used for its preparation and serving and the company of those participating in drinking it, has become one of the cornerstones of classic Japanese culture and the severe discipline it involves is very close to budo so it isn’t surprising that even battle-hardened warriors from the Kamakura to the Sengoku periods found merit in it. The Tochigi Budo Tourism Trial Tour included a visit to a beautiful garden, the Kikusuien Garden in Kanuma city where a group of sado practitioners from the Urasenke school made a brief introduction of sado and prepared for the participants tea and nerikiri sweets with an autumn leaves’ theme –seasonality being one of sado’s main characteristics.

Explanation about sado

Drinking tea

Appreciating the chawan (tea cup)

Zazen

Zazen instruction by Daioji priest, Kurazawa Bungyo

Zen Buddhism was introduced to Japan during the Heian Period but it was during the Kamakura and Muromachi Periods that it really took off and that was greatly because of its affiliation with higher-level bushi including the Ashikaga shoguns. Zen’s bare-to-basics approach to Buddhism and its ideas of non-attachment and the cultivation through Zazen sitting practice of a mind that is immovable by ideas, fears, anxieties or emotions, was very appealing to warriors’ leaders so it became part of the broader samurai culture regardless of the fact that it was rituals from the esoteric Buddhist sects Tendai and Shingon that were more popular among lower level samurai and budo practitioners. Adding a Zazen experience in the Tochigi Budo Tourism Trial Tour was a nice touch and allowed participants to see a Soto sect temple (Daioji in Otawara city) from the inside and sit in a real Zendo practice hall under the guidance of a Zen teacher. The sitting was just 15’ so everyone was able to do it and the priest’s explanations about rituals before and after it were also very interesting while strolling around the 600-year old temple’s grounds and seeing the thatched-roof buildings added to the overall experience.

Daijoi Temple gate

Daioji Temple’s kayabuki thatched-roof Hondo main hall (designated as National Important Cultural Property)

Sitting zazen at the Daioji Temple zendo (practice room)

PS

PS

Despite the fact that this was an experimental event, both TPSC and NTA managed to do a very good job and work around the unavoidable logistical and scheduling wrinkles. I am not sure if this will become a standing program or even if it does, if it will revolve around the same concept and involve the same activities but I think with some adjustments, it has the potential to become a major tourist attraction to a prefecture that has more depth than is usually given credit for. Even to Japanese (let alone overseas’ tourists) Tochigi means little more than the Nikko Toshogu mausoleum and its delicious strawberries; the world should know it’s more than that.

Day 1 lunch: Kappo Sansui-Tei (daimiyo cuisine) in Mibu

Day 2 lunch: Gyozakan (gyoza dumpling restaurant) in Utsunomiya

Day 3 lunch: local produce in Otawara

After lunch at the Otawara farmhouse

◎TOCHIGI PREFECTURE SPORTS COMMISION https://tochigi-pref-sports-commission.com/

◎TOCHIGI PREFECTURE KYUDO FEDERATION https://www.kyudo-tochigi.jp/

Grigoris Miliaresis