Paul Martin’s Sword-shaped Bridge

Interview and Text by Grigoris Miliaresis

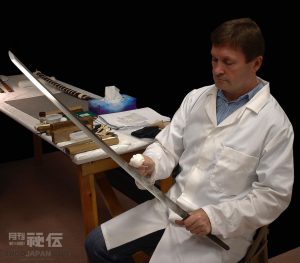

Sword cleaning at the British Museum

His is probably the first name non-Japanese hear when they start exploring the world of Japanese swords as objects of art, craftsmanship and culture. Any study of the swords –how they are made, how their construction, shape or function changed through the centuries, how they are now– invariably starts at the door of Paul Martin, one of the world’s leading Japanese sword experts, whose involvement with this most distinct among Japan’s symbols, goes back to the early 1990s and the Japanese section of the British Museum in London.

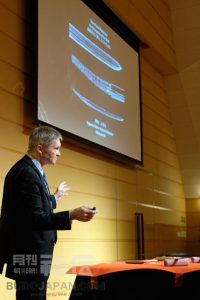

Paul Martin’s sword seminar

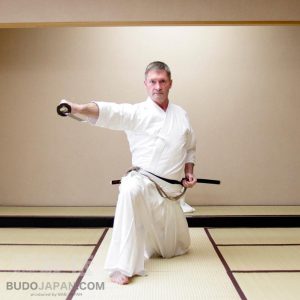

A Nihonto Bunka Shinko Kyokai Public Foundation trustee, designated Master of Culture for Kyoto’s Honganji Temple, Ministry of Tourism recognized specialist and the only non-Japanese to win the Tokyo sword appraisal competition (twice!) Paul Martin as also an accomplished martial artist: three times English karate champion and international level competitor with England’s team, 4th dan in kendo and 5th dan in iaido (he still practices Muso Shinden-ryu and ZNKR iaido) he was a member of the legendary Noma kendo dojo and practiced Ono-ha Itto-ryu under Torao Ono and Takemi Sasamori. In other words, his understanding of the sword comprises both the side of a professional connoisseur and that of an actual user –something we don’t see very often.

“Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba” prototype tsuba, on display at Fukushima’s Nisshinkan

I’ve always wanted to have a sit down with Paul Martin and the opportunity came from the latest in a long line of projects towards his life passion: promotion of the Japanese sword. Sparked by the unprecedented success of the manga/anime “Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba”, he decided to make a set of sword fittings (koshirae) for his own sword after the “Nichirin” sword of the manga’s protagonist, Tanjiro Kamado. Combining personal work and the help of acquaintances from the world of sword craftsmen he brought the sword to life and right now, his prototype tsuba is on display at Nisshinkan, the former school for the children of the Aizu Domain samurai in Fukushima’s Aizu Wakamatsu.

Paul Martin and Grigoris Miliaresis with the “Kimetsu no Yaiba” koshirae sword

Swords at the British Museum

Let’s start in reverse i.e. not from your last sword but from your first. What was the first sword you saw -and when?

Of course, I had seen swords in Kurosawa movies and in my all-time favorite movie, the Takakura Ken, Robert Mitchum “The Yakuza”, but never seen one in person. Then, in 1993 I joined the British Museum as a security guard and eventually wandered into the Japanese gallery where they had some wonderful swords on display with great explanations of the artistic qualities of the steel and its spiritual significance to the Japanese people. It was then that I was informed that the man in charge of the Japanese department was a sword specialist. This was incredible information to me: until that moment, I never realized such a profession existed! I think in that instant I discovered my life’s dream. As for the first, although I know the names of many of the better swords in the collection now, I cannot remember which I saw at that time.

The “sword specialist” was the legendary Victor Harris under whom you eventually ended up working. How did that happen?

Paul Martin and Victor Harris

Yes, my first sword teacher was Victor Harris. Before I joined the department, I would see him sometimes and ask him questions about swords and Japan; I don’t think that at that time either of us thought that I would become a member of his department! However, I had started studying swords properly: I had bought his book, “Swords of the Samurai”, joined the Token Society of Great Britain and before joining the Japanese department I also retired from karate and began kendo. I had also been teaching myself Japanese from a phrase book, and then talked Human Resources to allow me to go to Japanese language night school.

After one year as a security guard I became a security supervisor and after a further four years, someone in the Japanese department quit. It was an exciting moment: I had been told before that I should apply to the department, but there had been no positions available. However, at the time, the museum was still quite Victorian, and because of some strange rule I could not apply. So I complained to the head of HR, a very nice lady who, like everyone, knew that I was Japan mad and she changed the rules so that I could apply.

Could you say a few words about what you learned from Harris? Would it be fair to say that your time with him was an apprenticeship that gave you the foundation for your knowledge in swords?

Paul Martin with his Oshigata Competition prize

I was given the care of the sword collection under his guidance. Until then, other support staff had been afraid either because they were dangerous or because they are also easy to damage; Victor taught me how to care for them and I would hear him speak to the visitors who came to see them. He would give me tasks, that I didn’t realize immediately were part of my sword education. It was difficult at first as I didn’t know what questions to ask. However, Victor pretty much taught me in a Japanese way where I spent a lot of time watching and listening then was given tasks to do, like clean all the swords or find a sword by a certain maker, but most of all he had me looking at the swords a lot. One way he done this was to encourage me to draw oshigata i.e. hand drawings traditionally used for sword record-keeping.

Swords and swordsmanship

But Victor Harris didn’t just introduce you to swords -he also introduced you to classical swordsmanship, correct?

After I joined the department, he began teaching me Ono-ha Itto-ryu; he had studied it in Japan in the late 1960s under Jussei Ono and his son Torao and we used to practice in the basements of the museum or in the gallery in between exhibitions. Then, when we went to Japan together as representatives of the British Museum, to collect the 103 swords that had been restored in Japan and were later published in the “Cutting Edge” catalog, he introduced me to Torao Ono sensei.

Paul Martin practicing karate at age 7

England National Team 1992 (Paul Martin, first from right)

Winning the 1993 England All-ryuha Karate Championship

You have practiced both the modern approach to swordsmanship (kendo-iaido) and the classic (Ono-ha Itto-ryu). What did each of them bring to your understanding of the sword?

I have also practiced several other sword arts, including Batto-do and Hayashi-Ryu under Hayashi Kunishiro sensei. The thing that links them all together is the ultimate truths. We can only cut in eight basic straight lines and tsuki. There are other techniques that can be used with sheathed sword for locks and strikes, but the fundamental practical aspects of refined correct technique that works with the mechanics of the body, is the only way to produce effective cuts.

Paul Martin’s Iai

Paul Martin’s Iai

These two sides, that of the sword expert and that of the swordsmanship practitioner were there from the start. Do you think it’s necessary to have both to appreciate swords?

Nukiuchi

I don’t think it is “necessary” but it does give you a more rounded perspective. For example, when I see practitioners of battojutsu using swords that do not fit into the historical sword shape chart, I find it kind of strange. It is definitely not necessary for sword appraisers to be able to use swords, as they are just looking at historical objects that have been meticulously recorded and whether they can use a sword or not has no bearing; conversely, someone who is good at sword martial arts will not make his practice any better if he has a deep appraisal knowledge of swords. Having said that, I think that it is important for both martial artists and specialists to understand the deep spiritual and cultural meanings of Japanese swords.

On to Japan!

As you became more knowledgeable and with all this multi-level involvement with Japanese culture, it was unavoidable you would come to Japan to stay and study. When did that happen and how did your first time in Japan feel?

Having a drink with swordsmiths. L-R, Yoshihara Yoshindo, Yoshihara Yoshikazu, Paul Martin, Fujishiro Tatsuya

After joining the Japanese department at the British Museum I finally got to visit Japan as part of my job, couriering objects from our collections to and from Japan. On my first trip, I had no real surprises or culture-shock. I already spoke a little Japanese and had watched quite a number of Japanese movies but I was so excited that I think I did not sleep very much that week! I also made a point of visiting the Japanese sword museum, which at the time was in Sangubashi: it was like a dream come true. By the time of my second trip, I realized that I was allowed to extend my trips and take vacation time while in Japan so I used this time to plan trips within Japan and connect with our Japanese colleagues who would show me great swords from their collections or introduce me to other institutions or shrines with swords. I think that on about my third trip I realized that if I really wanted to study swords, I needed to move here. Besides, I had also fallen in love with the country!

And your actual move?

At the “The Japanese Sword: The Yoshihara Tradition” exhibition in California, 2005

Around 2002 the British Museum began downsizing and merging departments; also Victor was coming up for retirement. As I said earlier, it is somewhat Victorian in some ways, so promotion for me would have been rather difficult. I took the opportunity to take severance pay as part of the downsizing, left in 2003 and moved to California for one year, where I made a presentation to the Pacific Asia Museum in Pasadena, to host my “The Japanese Sword: The Yoshihara Tradition” exhibition. They accepted just before I moved to Japan in January 2004. The exhibition took place between March and June 2005 and at the time it was the exhibition with the largest attendance in the museum’s history.

How did you study sword in Japan?

Paul Martin and swordsmith Matsuda Tsuguyasu (Photo: Tom Kishida)

On some of my previous trips, I had been invited to various kantei-kai (sword appraisal events). So once I moved to Japan, I joined every kantei-kai I could find in Tokyo. I also went to different polishers’ studios, not to learn polishing, but to learn their process; not to mention they always have good swords to see! I also visited most other craftsmen and in some cases even tried their craft under their supervision so that I could have a better grasp of what was involved.

Kantei-kai: Sword contests

Can you say a few words about the competition you won twice?

The contest is the Society for Preservation of Japanese Art Swords (NBTHK) Tokyo Branch Ippon Nyusatsu (one guess per sword) and is open to sword enthusiasts but also professionals (polishers, swordsmiths, dealers etc.) I have taken seconds and thirds quite a lot, but the first time I won was in 2006, just over two years since moving here and the second time was in 2018. They put out five swords all with their tangs covered so you cannot see if they have any inscriptions of if they have been shortened in their lifetime, etc. If you guess the maker’s name, you get 20 points so to get 100 you need to get all five correct. However, if you guess slightly incorrectly (for example the teacher or the student’s work) you get 15 points and a slightly more incorrect guess gets 10 points. The winner is whoever gets the most points from one guess for each of the five swords. Time is also limited, about two hours, but you can only look at a sword for one minute at a time. However, you can line up as many times as you can inside the two hours.

| Six basic steps for sword appreciation by Paul Martin

1. Bow to the sword

2. Pick the sword from the pillow with both hands keeping the tip raised. Take away your left hand and hold it vertically in front of you at arms length so you can see its shape and understand the period it was made

3. Take the cloth with your left hand, lay the sword on it and point it towards the light to inspect the hamon (temper line); this often tells you who was the smith that made it

4. Lower and turn the sword so you can inspect the hues and textures of the folded steel; from this you can tell the area it was made and the school of smiths

5. Return the sword on the pillow

6. Bow to the sword once again

|

The “Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba” sword project

If someone looks at your activity it wouldn’t be an exaggeration to call you the leading evangelist of the Japanese sword in the English-speaking world. Was that on purpose?

After numerous TV appearances, translations of popular books and the production of a documentary, I came to a point where I realized that I was in a special position, one that no one has ever been in before. Also, because all my sword friends and teachers had trusted me with an incredible volume of information, I felt a great responsibility to correctly transmit that information around the world, to become a sword-shaped bridge between Japan and the rest of the world, if you will.

The “Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba” sword project certainly fits in this. Can you tell us a few things about it?

“Ichimatsu-Pattern” sword bag

I am not normally a fan of anime or manga, but I know that every generation has their introduction to Japanese swords. For mine, it was Akira Kurosawa, Takakura Ken movies and martial arts and for the ones following it was “Rurouni Kenshin”, “Token Ranbu” and now “Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba”. However, I felt that this was different to other manga: it presents the sword not only as a slayer of demons but also illustrates the spiritual and philosophical aspects of Japan and swords where the sword is a protector from evil. This fits with the Japanese sword’s role as spiritual protection (Omamori-Gatana) or as protector of justice and humanity –the “Katsujinken” we often see in kenjutsu schools. Furthermore, it introduces aspects such as the raw material tamahagane and the connection between smith and owner. I thought that by making a real Kamado Tanjiro koshirae in collaboration with traditional Japanese sword craftsmen, I might be able to harness the popularity of the series to introduce the real craft to a new generation of potential future sword craftsmen and academics (curators etc.)

| Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba Sword Fittings Project

Foundation (saya and tsuka wooden cores): Kuwano Toshiro Lacquer: Koyama Mitsuhide Tsukamaki: Hashimoto Yukinori Tsuba, fuchi, kashira and kojiri, koiguchi ring: Paul Martin (under the supervision of Izumi Koushiro)  Tsuba  Kashira  Kojiri  Tsuba For a step-by-step documentation of the making of the fittings, visit Paul Martin’s channel on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/TheJapaneseSword |

Our readers are mostly martial artists, many of who are, like you, practitioners of sword arts who might want to explore the swords themselves. Any advice or guidelines for them?

People around Japan are very fortunate because there are sword appreciation groups in most prefectures; also, there are many museums, public and private that display swords. I would advise joining your local Kantei/benkyo-kai. If you are interested in the crafts, try to support your local sword craftsmen. Some are open to visits and questions. At the moment in Japan there is a distinct lack of Habaki-shi and Saya-shi. It would be great to try to keep the traditions alive by injecting more young people into the crafts. It is incredibly important that the intangible skills are continued. If they are lost, I wonder how we would ever bring them back. However, this does not advocate the activities of amateur craftsmen who just try to teach themselves. There has been irreparable damage done to swords and their history by amateur attempts at restoration.

Grigoris Miliaresis

About the interviewer

Grigoris Miliaresis has been practicing Japanese martial arts since 1986. He has dan grades in judo, aikido and iaido and has translated in Greek over 30 martial arts’ books including Jigoro Kano’s “Kodokan Judo”, Yagyu Munenori’s “The Life-Giving Sword”, Miyamoto Musashi’s “Book of Five Rings”, Takuan Shoho’s “The Unfettered Mind” and Donn Draeger’s “Martial Arts and Ways of Japan” trilogy. Since 2007 his practice has been exclusively in classic schools: Tenshin Buko-ryu Heiho under Ellis Amdur in Greece and Kent Sorensen in Japan and, since 2016, Ono-ha Itto-ryu under 17th headmaster Sasamori Takemi and 18th headmaster Yabuki Yuji.

http://about.me/grigorismiliaresis