Kashima Shinden Jikishinkage-ryu: breath in, breath out, step in, step out

Text by Grigoris Miliaresis

Tenshin Shoden Katori Shinto-ryu does it with fast, long and complicated kata, Morishige-ryu with splendid armors and explosive sounds and Araki-ryu with an amazing variety of weapons. But Kashima Shinden Jikishinkage-ryu’s way to make you stop and watch is perhaps koryu world’s most unexpected: dressed in white and armed with extra thick bokuto (their tsuka diameter is about 4.5cm/1.7” and they weigh 1.4kg/3 lbs) the members of the school engage in what looks like a ritual dance with incredibly slow walking, arms wide open, audible breathing, long and loud kiai and often cuts standing on one leg –this from a school that defined the idea of gekiken i.e. kendo before it became kendo!

Jikishinkage-ryu’s weapons; at the top are the furibo and the extra thick bokuto

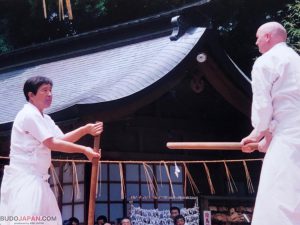

20th Headmaster Yoshida Hajime and Hudson Shihan at the Kashima Shrine Kobudo Hono Enbu ca. 2005/2006

From the first time I saw it, very appropriately at Kashima Jingu, I knew I had to learn more about this school. And I did: it was created by Matsumoto Bizen-no-Kami Naokatsu (1467-1524) whose family was involved with Kashima Jingu, drew its influence from one of kenjutsu’s primordial schools, Kage-ryu, and its second patriarch was Kamiizumi Ise-no-Kami Nobutsuna (1508-1577) of Yagyu Shinkage-ryu fame; the school changed several names until its 7th generation headmaster, Yamada Mitsunori (1639-1716) came up with “Kashima Shinden Jikishinkage-ryu”. However, its most famous exponents were its 13th, 14th and 15th headmasters, Otani Nobutomo (1798-1864), Sakakibara Kenkichi (1830-1894) and Yamada Jirokichi (1863–1930): they saw it through the late Edo, Meiji, Taisho and early Showa periods, encouraged gekiken practice and even came up with Gekiken Kogyo, events featuring sword, naginata and kusarigama matches that allowed recently unemployed samurai and martial artists to earn a living using their skills. The rest of the 20th century saw Jikishinkage-ryu flourish by breaking down: there’s over half a dozen organizations from different lines, some practicing kata and gekiken, others just kata split in five groups: Hojo no Kata (the aforementioned slow kata), To no Kata or Fukuro Shinai no Kata (practiced with an unusual fukuro shinai), Kodachi no Kata (featuring a 98.5cm/3’2” long kodachi), Habiki no Kata (practiced with habiki, real swords without an edge) and Marubashi no Kata, practiced with shinken (live blades) but rarely demonstrated.

17th Headmaster Ohnishi Hidetaka and 18th Headmaster Namiki Yasushi at the Yasukuni Shrine performing Hojo ca. early 1960s.

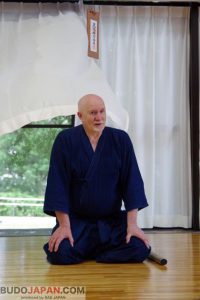

With so many lines/dojo, where should a “Hiden” writer go for an experience story? Starting from a line called “Seito-ha” (“main”) seemed like a good idea and I found out that this line, going from Yamada Jirokichi to present day Tanaka Mitsushi was the one I’d seen at Kashima Jingu. What’s more, its Kenshukai dojo, is run by an Englishman, Michael Hudson! Hudson-sensei is a rare breed, even in a world like that of koryu, inhabited by definition by rare breeds: he came to Japan to practice aikido, became interested in Kashima Shinden Jikishinkage-ryu, enrolled in 1984 under Namiki Yasushi, the 18th doto (the school uses this Confucian term for its headmasters), started a separate group for people who couldn’t attend regular practice in 1996, continued practicing under 20th headmaster Yoshida Hajime and in 2006 became shihan and was awarded menkyo kaiden by him.

19th Headmaster Ito Masayuki and Hudson Shihan in 1984, the year he joined the school.

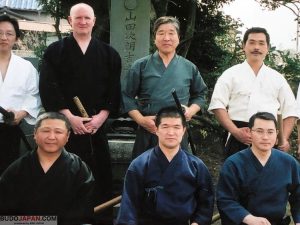

Hudson Shihan, Yoshida Sensei and Kawashima Noriyoshi Shihandai around 1998/1999. Kawashima Sensei led the Shinagawa Hojokai group.

A group photo of the participants at Yamada Jirokichi annual graveside Enbu ca. 2010/2011. In front of Hudson Shihan to the right is Tanaka Mitsushi, present day (21st) Headmaster. In front of Yoshida Sensei to his left is Shimakura Minoru, Hudson Shihan’s student.

Yoshida Sensei and Hudson Shihan at 15th Headmaster’s Yamada Jirokichi graveside Enbu in Chiba ken. ca. 2005-2007

What makes Hudson-sensei even more exceptional is his focus: completely outside the koryu circuit, he’s based in the Tama City Budokan (incidentally, an amazing facility and location), leads a group of 15 very dedicated people aged from 29 to 80+ years old and practices week after week, year after year, intensely but obviously enjoyably the art he’s chosen. No frills, small-talk, over-teaching or theorizing: just real, sincere practice of a school incredibly more complicated than it looks.

The basics

All teachers of any rank in any school, stress the importance of kihon, basics. But what is “kihon”? To Jikishinkage-ryu it’s breathing (no air, no survival) and walking (no walking, no movement) so after 15 minutes of one suburi, called Ichi Enso (“enso” as in Zen’s circles) and consisting of overhead cuts with swings of the big bokuto alternating over the left and right shoulder, comes the first Jikishinkage-ryu technique: it’s Unpo i.e. standing opposite your partner, hiking your hakama up (aka “momodachi”) and then walking very slowly towards them while breathing in three stages -inhale, hold, exhale. You advance starting with the left foot and your partner retreats starting with the right and pay special attention on how you place your foot (heel to toes), how the toes grab the floor upon contact and how you contract and expand your diaphragm and abdomen (i.e. hara) -to help with that, the hands are placed on the abdomen forming a triangle (thumbs and forefingers touching).

Ichi Enso 1

Ichi Enso 2

To make the movement more alive, breathing is audible and at beginner level, performed inhale-through-the-mouth and exhale-through-the-nose-style; this sounds counter-intuitive but the rationale is that this way the teacher can hear if the students breath correctly; after a certain level they can breath in an in-and-out-through-the nose way. Because Jikishinkage-ryu puts so much emphasis on breathing and walking, every micro-movement is magnified so both teacher and student know what’s happening and strive to improve it and create the perfect Jikishinkage-ryu body; incidentally, for its breathing pattern the school uses the terminology “A-Un” as in “Om”, “beginning and end of everything” and the open and closed mouths of Nio deities guarding Buddhist temples. I did Unpo with Hudson-sensei and immediately realized I had to do it with him: this practice is so intense and meticulous that you simply cannot do it without the teacher overlooking your every twitch!

Unpo

Four seasons

If you thought Unpo was hard, wait until the next step: Hojo, aka “Four Seasons” aka Jikishinkage-ryu’s slow, ritualistic, big bokuto trademark kata. These four kata are attributed to founder Matsumoto Naokatsu and using the four seasons as symbols, teach different ways to breath and move: Haru/Sping is lively, Natsu/Summer is fast and aggressive, Aki/Fall is changeable (fast and slow) and Fuyu/Winter is slow, subdued and quiet. Each kata also has a second name which, as I found out, comes from the 12th century Zen koan collection “Hekiganroku” (“Blue Cliff Record”); they are Hasso Happa (eight-direction explosion), Itto Ryodan (decisive cut), Uten Saten (right turn, left turn) and Chotan Ichimi (long and short is the same) and yes, three of them are also used in Yagyu Shinkage-ryu’s Sangakuen no Tachi kata -remember the Kage-ryu/Kamiizumi Nobutsuna connection?

Given Jikishinkage-ryu’s attention to detail we only worked on Haru/Spring: standing opposite your partner you perform a sonkyo (squatting) rei, then both put the sword down, do a short Unpo away from the sword and then back, pick it up with one hand, bring it in front of your eyes and describe a big half-circle called Kami-hanen (upper half circle) symbolizing the beginning; in the kata’s end, you do the opposite (Shimo-hanen/lower half circle) closing the circle. When the hands are at the top you stand on your toes and inhale and when Kami-hanen is finished you are in the Tenchi (heaven-and-earth) stance with the sword on the right hand pointing upwards (heaven), the index finger of the left hand pointing down (earth) and the body (i.e. man) uniting the two.

Kami-hanen (upper half circle) 1

Kami-hanen (upper half circle) 2

Kami-hanen (upper half circle) 3

Kami-hanen (upper half circle) 4

Kami-hanen (upper half circle) 5

Kami-hanen (upper half circle) 6

Then, you bring the sword above the eyes as if shading them from the rising sun (“kazashi”) and the “action” starts: shidachi takes jodan and uchidachi wakigamae, then uchidachi goes to jodan and shidachi to hasso (Jikishiknage-ryu’s jodan is with hands over-extended and the sword parallel to the ground; hasso also has the same sword position but to the side of the head), approach each other and perform downward cuts, uchidachi goes to wakigamae, shidachi moves in bringing the sword to the hips, uchidachi retreats, shidachi thrusts and uchidachi blocks bringing his sword to a horizontal position. The two swords end up in a cross, uchidachi pushes shidachi back, they disengage, simultaneously cut downward (shidachi from jodan and uchidachi from hasso), then both repeat downward cuts from jodan, shidachi steps 45° to uchidachi’s right, takes a big jodan (called “Nio Dachi” -again a reference to the Nio statues’ postures) and cuts down the sword that uchidachi holds parallel to allow his partner practice a strong cut; this action tests whether shidachi’s cut is effective and symbolizes cutting the head at a seppuku ritual. After that, both take chudan, return to the center and finish.

Hojo no Kata/Haru (Hasso Happa) 1, shidachi (right) uchidachi(left)

Hojo no Kata/Haru (Hasso Happa) 2

Hojo no Kata/Haru (Hasso Happa) 3

Hojo no Kata/Haru (Hasso Happa) 4, shidachi takes jodan and uchidachi wakigamae

Hojo no Kata/Haru (Hasso Happa) 5, uchidachi goes to jodan and shidachi to hasso

Hojo no Kata/Haru (Hasso Happa) 6, approach each other and perform downward cuts

Hojo no Kata/Haru (Hasso Happa) 7, uchidachi (right) goes to wakigamae, shidachi (left) moves in bringing the sword to the hips

Hojo no Kata/Haru (Hasso Happa) 8, uchidachi retreats, shidachi thrusts and uchidachi blocks bringing his sword to a horizontal position

Hojo no Kata/Haru (Hasso Happa) 9, The two swords end up in a cross, uchidachi pushes shidachi back

Hojo no Kata/Haru (Hasso Happa) 10, simultaneously cut downward (shidachi from jodan and uchidachi from hasso)

Hojo no Kata/Haru (Hasso Happa) 11, shidachi steps 45° to uchidachi’s right takes a big jodan and cuts down uchidachi’s sword

Hojo no Kata/Haru (Hasso Happa) 12, uchidachi holds his sword parallel to the ground to allow his partner practice a strong cut

Nothing too complicated for someone with even a rudimentary understanding of kenjutsu, but believe me: it’s much harder than it looks because everything is done with the excruciating attention to detail I described for Unpo. Every step, movement, inhalation, hold and exhalation, kiai, angle of the sword and flexing and straightening of the muscles is done with chess grandmaster-deliberation, aiming for the day everything will become ingrained in your system and you’ll be able to perform them in the four ways indicated by Hojo’s seasons (which, are also reflected in the other sets of kata: To no Kata are spring, Kodachi are summer, Habiki are autumn and Marubashi are winter) and alternate these ways according to any encounter’s needs.

“Real” kenjutsu

The counterpart to Hojo’s stylized movements is To no Kata aka Fukuro Shinai no Kata: faster, freer and performed with a shinai that looks like a kendo shinai squeezed down and with its top leather part (sakigawa) lengthened to cover almost all of the bamboo slates, but unlike kendo shinai, with a real sword’s dimensions (125cm/3’3” length, 700gr/24 oz weight), these 14 kata are a reminder of Jikishinkage-ryu’s gekiken past and it’s where the teachings of Unpo and Hojo become really real! We worked on the first kata with both parties starting in a very Kashima-esque gedan kamae and then step towards each other, shidachi cuts twice yokomen and uchidachi blocks the attacks, then shidachi goes to jodan, uchjidachi retreats and attacks kesagiri which shidachi evades, then uchidachi retreats and attacks gyaku kesagiri which shidachi blocks, attacks once again yokomen (or left kote) which shidachi evades and the kata ends.

The counterpart to Hojo’s stylized movements is To no Kata aka Fukuro Shinai no Kata: faster, freer and performed with a shinai that looks like a kendo shinai squeezed down and with its top leather part (sakigawa) lengthened to cover almost all of the bamboo slates, but unlike kendo shinai, with a real sword’s dimensions (125cm/3’3” length, 700gr/24 oz weight), these 14 kata are a reminder of Jikishinkage-ryu’s gekiken past and it’s where the teachings of Unpo and Hojo become really real! We worked on the first kata with both parties starting in a very Kashima-esque gedan kamae and then step towards each other, shidachi cuts twice yokomen and uchidachi blocks the attacks, then shidachi goes to jodan, uchjidachi retreats and attacks kesagiri which shidachi evades, then uchidachi retreats and attacks gyaku kesagiri which shidachi blocks, attacks once again yokomen (or left kote) which shidachi evades and the kata ends.

To no Kata (Ryubi) 1, shidachi (left) and uchidachi (right) starting in a very Kashima-esque gedan kamae

To no Kata (Ryubi) 2, uchidachi and shidachi step towards each other

To no Kata(Ryubi) 3, shidachi cuts twice yokomen and uchidachi blocks the attacks

To no Kata (Ryubi) 4,

To no Kata (Ryubi) 5, shidachi goes to jodan, uchidachi retreats and attacks kesagiri which shidachi evades

To no Kata (Ryubi) 6,

To no Kata (Ryubi) 7, uchidachi retreats and attacks gyaku kesagiri which shidachi blocks

To no Kata (Ryubi) 8, uchidachi attacks once again yokomen (or left kote) which shidachi evades and the kata ends

Doing this kata (called “Ryubi”, “Dragon’s Tail”) should had been an exhilarating experience -and it was, because I fell back into the movement I knew. When I tried to incorporate the breathing, deliberate walking and internal and external moving from Unpo and Hojo (because they must be incorporated!) I had to start all over again, with Hudson-sensei smilingly remarking “it isn’t as easy as it looks”. The fact remains though: this set, coming right after Hojo is the practical application of what you’ve learned so far and a laboratory to explore a wide range of situations that will come up in real confrontations –for those who have only seen Hojo, To is a reminder that Jikishinkage-ryu is as real kenjutsu as it gets!

Swinging the impossible

No account of Kashima Shinden Jikishinkage-ryu would be complete without mentioning the massive furibo, invented by Sakakibara Kenkichi as a tool for building the Jikishinkage-ryu body, breathing and mind. The basic exercise is the Ichi Enso I mentioned earlier but imagine doing it with an 180cm/5’9”, 8kg/17.6 lbs log. Mr. Minoru Shimakura, Kenshukai’s number two, was kind enough to lend me his and show me how to swing it; Hudson-sensei pointed out that if the body movement isn’t 100% correct, the furibo (“swinging club”) becomes “muribo” (“impossible club”). To avoid damaging the Budokan’s floor I tried it on the tatami next door and from the first swing I saw what he meant: you need to allow it swing, follow it behind your back and over your head and then direct it in front of you, stopping it like a sword in an overhead cut. Yes, it’s doable, but extremely difficult!

Furibo 1

Furibo 2

Furibo 3

Furibo 4

Furibo 5

Furibo 6

The author trying furibo

Bowing out

Among the schools I have seen and tried, Kashima Shinden Jikishinkage-ryu is undoubtedly the most perplexing. It’s sophistication in breathing (kiai included) and internal body work would bring tears of joy to a Chinese Neijia instructor but what’s even more amazing is how this practice built through Unpo (which, together with Ichi Enso is all beginners do for their first three months) and Hojo, informs regular kenjutsu skills as those in To no Kata -it didn’t happen to me but it was obvious in the movement of Kenshukai’s members and although they don’t practice that way, I’d like to see them do freestyle in kendo bogu. The three hours at Tama City Budokan were both gratifying and humbling: over 30 years of martial arts’ practice barely kept me a few steps behind what was happening and the experience made my respect for this historic school and its practitioners grow. Their exemplary hospitality aside, Hudson-sensei and his students are what most people think of as “genuine koryu” and anyone who wants to experience a still vibrant and very much relevant classic kenjutsu tradition should definitely pay them a visit –I for one, will be always grateful to them for the lesson!

Kashima Shinden Jikishinkage-ryu, Keishukai, group photo at the end of the practice

PS

Oh, those cuts done standing on one leg? That’s balance practice: if breathing is correct, balance is too.

PPS

I usually reserve my thank-yous for the instructors who devote their time to us and their students whose practice we disrupt. This time though I must extend my gratitude to Tony Cundy whose 2002 “Kendo World” article was an amazing introduction to Kashima Shinden Jikishinkage-ryu and Nathan Morrison, a Rokugo Dojo practitioner who was always willing to answer questions and help me untangle the school’s postwar development. Without them, this article wouldn’t have been possible.

Grigoris Miliaresis

About the author

Grigoris Miliaresis has been practicing Japanese martial arts since 1986. He has dan grades in judo, aikido and iaido and has translated in Greek over 30 martial arts’ books including Jigoro Kano’s “Kodokan Judo”, Yagyu Munenori’s “The Life-Giving Sword”, Miyamoto Musashi’s “Book of Five Rings”, Takuan Shoho’s “The Unfettered Mind” and Donn Draeger’s “Martial Arts and Ways of Japan” trilogy. Since 2007 his practice has been exclusively in classic schools: Tenshin Buko-ryu Heiho under Ellis Amdur in Greece and Kent Sorensen in Japan and, since 2016, Ono-ha Itto-ryu under 17th headmaster Sasamori Takemi and 18th headmaster Yabuki Yuji.

http://about.me/grigorismiliaresis