“The Sword and the Chrysanthemum” by Paul Martin Part4: Materials Used to Make Japanese Swords

Text by Paul Martin

Paul Martin and his Kamon(Photo/Steve Morin)

Each installment of this series is available for a limited time only—don’t miss it!

(Publication period: January 14, 2026 – February 13, 2026)

The raw materials used in the manufacture of Japanese swords is generally referred to as tamahagane. Tamahagane is produced using the Tatara-buki method of iron and steel production. However, particularly in the modern age, there are various methods used to produce traditional Japanese steel for swords based upon the tatara method. Steel produced by these methods is also generally known as Watetsu (Japanese steel). It is speculated that the tale in the Kojiki (Ancient Chronicles of Japan) about the mythological eight-headed eight-tailed dragon-serpent called Yamata-no-Orochi, in which’s tail the imperial regalia sword – Murakumo-no-Tsurugi (later Kusanagi-no-Tsurugi) was discovered when it was slain by the storm god Susanoo in the Oku-izumo region, could be a metaphor for the tatara method of steel making.

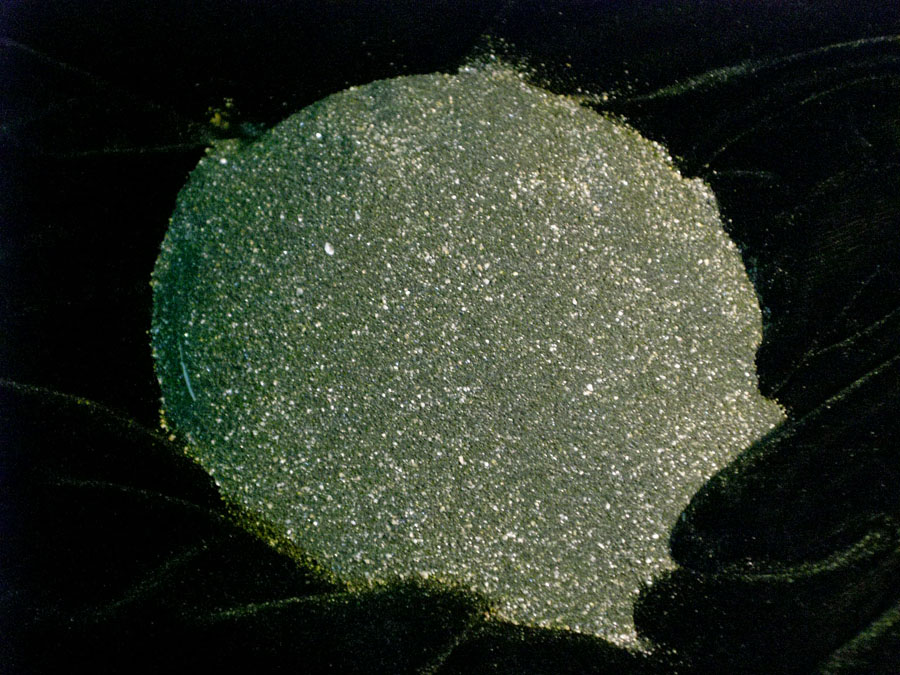

Sand iron

Japan was rather late entering into the iron-age. The origins of the word, tatara, is thought to have come from the Hittites (Anatolia,Turkey) who were making steel around 1500 BC. The word, along with iron making itself, is thought to have travelled to Japan via the silk road. As Japan was lacking in iron-ore, it was imported from the Asian continent. However, importing iron-ore was very expensive, and it was discovered that Japan was rich in sand-iron. Due to this discovery, it is thought that the tatara method of iron making from sand-iron developed in the late Kofun period around the mid 6th century. The word, tatara, is first used in the Nihon Shoki (Chronicle of Japan), but at that time it is thought to have meant producing wind via bellows. However, it later it took on a general meaning for this type of iron and steel production.

Kanayago Shrine in Yasugi City

Since the earliest iron producing times, the San’in region has been a center of tamahagane manufacture in Japan. It is said that Kanayago, the female deity of steel making and a patron deity to blacksmiths, flew in on the back of an egret and landed in a katsura tree. It is said that it was the head priest, Abe Masashige (安倍正重), who first discovered Kanayago in a Katsura tree, and built a shrine on the next to the spot. Kanayago then instructed the locals on how to produce iron. As with most tatara sites, a small shrine dedicated to Kanayago is installed close to the tatara. Kanayago is also said to be a jealous deity. Women were discouraged from entering any sites of steel production or smith’s forges, and men were advised to make their prayers to her shrine alone. The main Kanayago Shrine in Yasugi City, Shimane has several devoted old large rectangular blooms of iron and steel called kera on its grounds. The head priests of the shrine have been successive generations of the Abe family. Generations of Murage (tatara foremen) in the area would come to pray for success in production, and guidance at times when problems arose. This meant that the various generations of Abe priests became knowledgeable advisors to the Murage.

Kanna-nagashi (the collection of sand-iron)

The base material from which tamahagane is produced is called satestu (sand iron). Satetsu was collected between October and March during the agricultural off-season so as not to disturb the local farmers by polluting the rivers during crop seasons. During this period, the waterways were not needed for rice production, so the they could be used for sand-iron collection while the farmers carry out other duties such as harvesting and other farming.

The Hino River in Tottori Prefecture. It holds a history and culture of collecting iron sand as raw material for tatara iron smelting, which has been actively practiced in the watershed since ancient times.

The sand-iron would be mined from cliff sides and flowed down rivers to remove other lighter sediments. The heavier sand iron would sink and then be collected from the river beds and special collection reservoirs. This made many of the rivers in the area run red from the oxidation of the sand-iron in the ware. As the process evolved, separate man-made waterways and aqueducts were utilized.

Production of Tamahagane Through Tatara-buki

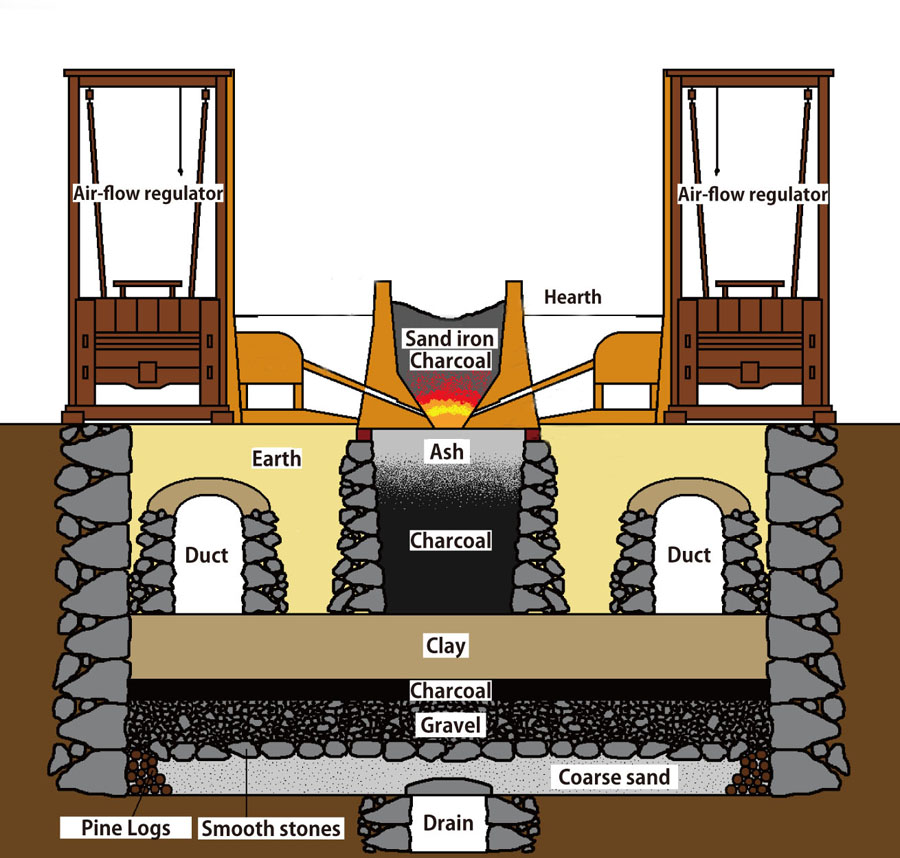

Nittoho Tatara Cross sectional Diagram(Wikimedia Commons 三條千秋, CC BY-SA 4.0,)

The process of producing tamahagane is called tatara-buki in which large clay furnace, called a tatara, is used to smelt the sand-iron. To produce the optimum environment in which to make tamahagane it is important that moisture in kept to a minimum. To combat this, the tatara smelter is built on top of a large underground structure of up to three-meters deep. The structure includes air ducts, called ko-bune, through which the moisture is drawn out during the manufacture process. In addition, the tatara is operated in late January early February every year when humidity levels are at their lowest.

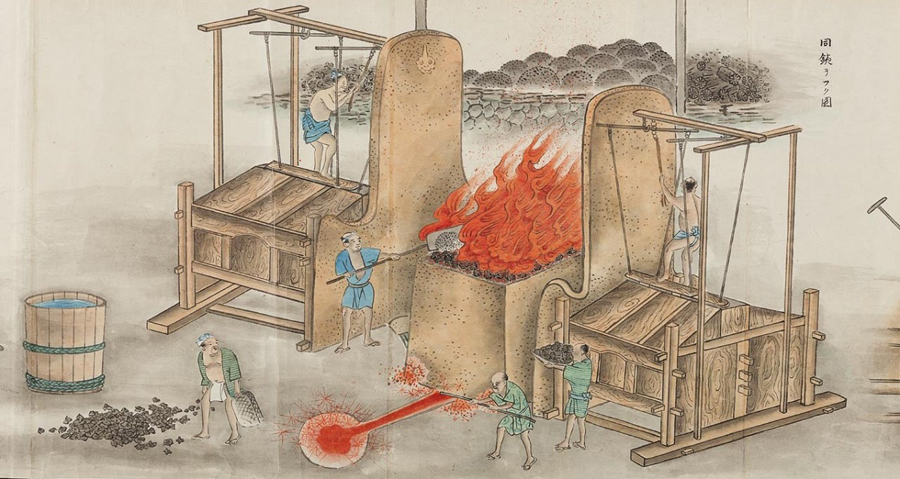

Diagram of Washing Iron Sand at Mount Yamagami, Sendaizu Agawa Village Late Edo Period (Tokyo University Library of Engineering and Information Science, Engineering Library Room 4, Collection A)

Tatara-buki method Since the Meiji Era and Its Revival

Following the introduction of modern steel production techniques to Japan, by 1925 the tatara-buki method was no longer used and had been replaced with western blast furnace production methods. However, with Japan’s expansion into Asia and the approach of WWII, the demand for traditional Japanese swords for the military led to the resurrection of the tatara-buki method. In 1933 at Yokota-cho, Shimane prefecture the Yasukuni tatara was constructed to provide tamahagane for the Nihonto Tanren Kai at Yasukuni shrine in Tokyo. Where swordsmith’s known as Yasukuni Tosho (Swordsmiths of Yasukuni Shrine) produced swords commonly known as Yasukuni-to (Yasukuni swords) and are highly prized as traditionally made Japanese swords. The site of the forges still remains at the rear of Ysukuni Shrine today, and nowadays serves as a Tea House for Traditional Tea Ceremony. Following Japan’s defeat at the end of the war in 1945, the Yasukuni tatara was closed once again.

Postwar Preservation of Japanese Swords and the Continuation of Tatara-buki

After the confiscation and near destruction of Japanese swords by the occupying allied forces, the Nihon Bijutsu Token Hozon Kyokai (NBTHK—The Society for the Preservation of Japanese Art Swords) was formed. One of the objectives of the NBTHK was to preserve the Japanese sword and its production as a traditional culture. In 1976, with the support of the national treasury, the NBTHK (also known as Nittoho) re-instated the tatara to its former glory by using the underground structure of the former Yasukuni tatara. Consequently, the minister of education designated tamahagane production as a Traditional craft for preservation. By 1977 Finance Minister Toshiki Kaifu had designated the Nittoho Tatara as a site of selected conservation techniques worthy of preservation. As well as being the main source of tamahagane production for Japanese swordsmiths, The NBTHK also train craftsmen in tamahagane production. The knowledge of Murage has been passed down from teacher to student over a long period of time. Former Murage (tatara operators), the late Abe Yosizou and Kumura Kanji were appointed as authorised conservators of the traditional craft of tamahagane manufacture, followed by Kihara Akira (appointed in 1986), and Katsuhiko Watanabe (appointed in 2002).

The NBTHK Tatara Production Process

Modern Tatara

The NBTHK tatara usually operates for three weeks. This is enough time for three cycles: one cycle takes seven days to complete. Day one is ground preparation. A layer of ash and charcoal is compacted by two rows of men facing each other with 12 ft wooden poles and take turns to beat the ground in order to compact the ash and charcoal in order to make a solid base upon which to build the clay furnace. Day two, locally sourced (fire resistant) clay is shovelled into a cast to make large clay bricks, then placed over the substructure and built up into an oblong altar like shape. Then some lit charcoal is placed inside the tatara to dry out the clay walls. On days three, four and five, the main phase of the tatara operation takes place over three days and nights. This is 72-hour non-stop cycle of smelting by adding sand iron and charcoal every thirty minutes. The temperature in the furnace maintained at around 1500∞ C. The Murage checks the condition of the melting sand iron by inspecting the molten slag that is expelled through vent holes at the ends of the clay furnace. By the end of the process, some of the initial 20-40 cm thick silica furnace walls have reduced to around 10 cm having become incorporated into the smelt to assist in the removal of slag.

Tatara Clay Furnace

When the Murage deems that the time is right, the walls of the tatara are torn down and a large rectangular bloom of iron and steel called a kera is revealed. The kera is approximately 2.7 meters in length by one meter wide and 30cm deep, weighing between two and two and a half tons. Two cores of tamahagane are produced within both the sides of the kera where the air supplied by wooden pipes pumped in by the automated bellows provided optimum deoxidization. Outside of these two cores are lower grade tamahagane, pig-iron, and okajiyou (a mix of pig-iron, steel, semi-reduced steel, slag and charcoal etc). The kera is left to cool and later dragged out to another workshop where day seven it is broken and graded by hand before it will be distributed to swordsmiths. The next day the cycle begins again.

The NBTHK guide to grading Tamahagane.

First grade tamahagane has an even of carbon content distribution of 1-1.5%.

Second grade tamahagane has a carbon content ranging between 0.5-1.2%

Mejiro is identical to first grade tamahagane, but is in pieces no larger than 2cm.

Zuku (Pig-iron) has a carbon content over 1.75 carbon and can be melted.

Okajiyou, is a mix of pig-iron, steel, semi-reduced steel, slag and charcoal etc.

Doushita, is identical to second grade tamahagane, but in pieces no larger than 2cm.

Tamahagane

Other Modern Tatara

The 25th Generation Choemon Tanabe resides in the village of Yoshida-cho, Shimane prefecture. The Tanabe family were one of the major producers of iron and steel in the area during the Edo period. The family still owns what was Japan’s last fully operational tatara (Sugaya Tatara: Important Cultural Property) that stands in Unnan City, Shimane Prefecture. However, Tanabe Choeman decided to revitalize his family’s legacy, and reconstruct a tatara complex in Yoshida-cho. It is somewhat smaller in proportion, and incorporates the use of some modern technology, but operates a few times a year providing a tamahagane making experience to many enthusiasts and supplying various craftsmen with tamahagane.

Sugaya Tatara High Kiln (Unnan City, Shimane Prefecture)

Other Methods of Watetsu (Japanese steel) Production

Jika-seitetsu

Jika-seitetsu is essentially the same method as the tatara-buki method, but much smaller in scale. It utilizes a small clay furnace, or a clay lined reusable metal furnace. A rather literal translation of Jika-seitetsu is ‘Home-made’ steel.

Zuku-oshi

Another iron smelting method in the realm of tatara is called, zuku-oshi. It is a two-stage iron production method using common sand-iron called, akome, that is smelted using charcoal to produce pig iron (zuku). As pig iron’s carbon content is too high, it is too brittle for swordmaking. Therefore, it has to be decarbonized to produce a suitable steel.

Oroshigane.

Oroshigane refers to the process of using various old iron products such as nails, gate hinges and kettles, etc made from old watetsu and smelting them to adjust the carbon content of to a level suitable for Japanese swords. For example, zuku (pig iron) a high carbon content, so the carbon is reduced (decarburization), while low carbon content iron need to have the carbon content increased (carbon absorption) to make it suitable for swords. Modern made tamahagane may be mixed with oroshigane to adjust the carbon content not only to make it suitable for swords, but to also in an effort to create a specific type of jigane that the smith is aiming for.

Nanbantetsu

Japanese swords have been known to have been made using Nanbantetsu (Western steel brought as ballast) That was brought by the Dutch and Portugese. This included, Echizen Yasutsugu, who was employed by the shogunate. However, it is not clear whether they used only nanbantetsu to produce those swords, or whether it was mixed with Japanese steel to adjust the carbon content.

Meteorite

Occasionally using meteorite (intetsu/inseki). However, as the carbon content is too low to produce a hamon, alternate methods are used, such as mixing steels with tamahagane, or using tamahagane for the cutting edge.