“The Sword and the Chrysanthemum” by Paul Martin Part3: Changes in the Shape of the Japanese Sword

Text by Paul Martin

Paul Martin and his Kamon(Photo/Steve Morin)

Each installment of this series is available for a limited time only—don’t miss it!

(Publication period: January 14, 2026 – February 13, 2026)

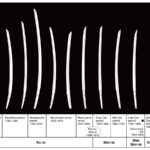

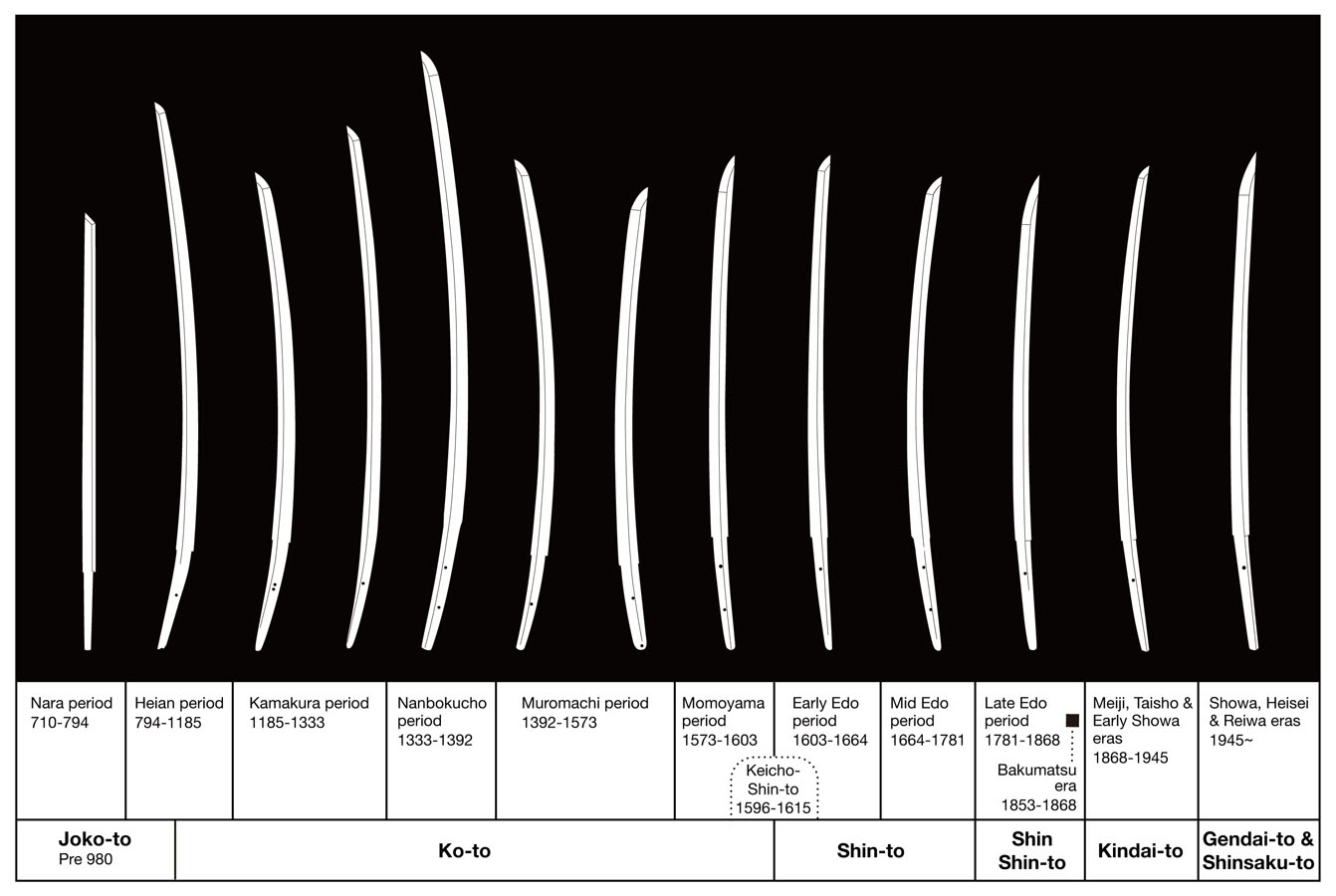

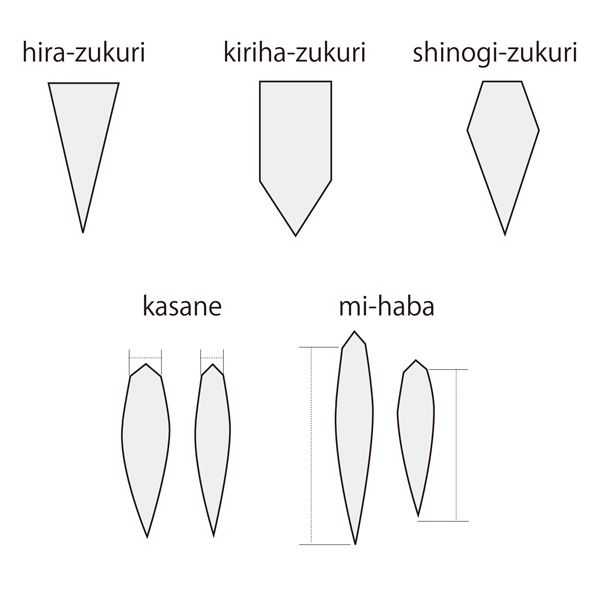

In the previous chapter, we discussed the three main elements of Japanese swords: sugata (the shape), jigane (the hues, textures and grain patterns) and hamon (the pattern of the hardened edge). This chapter focuses on the changes in shape that occurred in various periods of Japanese history. By recognizing the typical blade shapes from different periods helps us to assess the period in which a particular blade was produced. Both the curvature and the geometry of Japanese blades have undergone many changes according to the requirements of the various historical periods. However, the most noticeable change is the changes in curvature. The chart illustrates the changes in shape in the different historical eras.

the changes in shape in the different historical eras

1. Jokoto: Swords of the Ancient Period

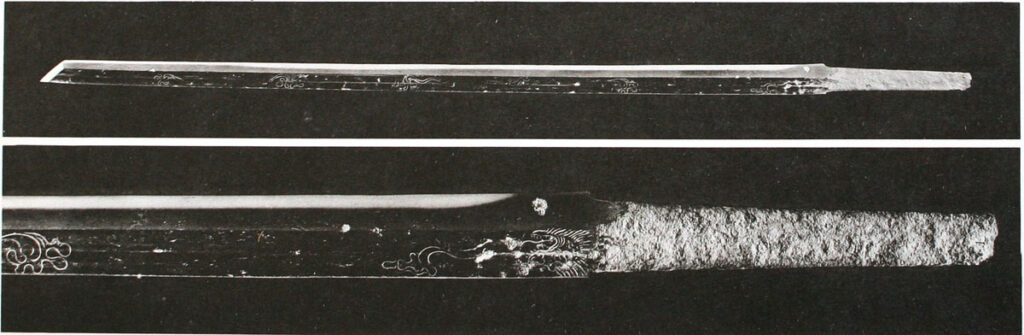

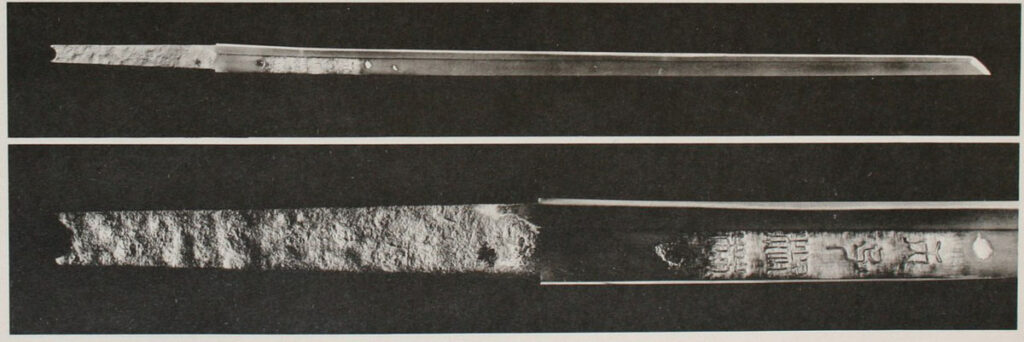

Before the emergence of the curved tachi, straight tachi blades called Chokuto were originally brought to Japan from the Asian continent. Later, during the Kofun period (300 AD -538 AD) sword making began to flourish in Japan with makers continuing the manufacture of straight swords in similar styles. They are usually constructed in the hira-zukuri (without ridgeline) and kiriha-zukuri (the ridgeline is closer to the cutting edge) styles. Many of these straight blades have been excavated from Kofun period tombs, and some were stored in the Shosoin Imperial Repository, Nara. There are no extant signed blades from this period. However, many have silver inlaid engravings. Two kiriha chokuto, that are designated as National Treasures of Japan that are housed in Shitennoji Temple in Osaka, are said to have come from China and were owned by Prince Shotoku Taishi (593-622). One is called the Shichi-Sei-Ken (Seven Stars Sword) because it has gold inlaid designs of various constellations, the main one being Ursa-Major (the Big-Dipper). The other one is called the Heishi-Shorin-Ken (丙子椒林剣) that is. It has four gold characters inlaid into the surface of the blade, that when read with Japanese readings are pronounced as Heishi-Shorin. It is theorized that two of the characters correspond with the Chinese calendar dating to the 6th C, and that the other two characters may relate to the maker’s name.

Great Bear sword or Seven Stars Sword, The sword contains a gold inlay of clouds and seven stars forming the Great Bear constellation. According to a document at Shitennō-ji, this sword was owned by Prince Shōtoku., Asuka period, 7th century , 62.1 cm (24.4 in) Osaka Shitennō-ji, Osaka, Japan

The sword contains an inscription in gold inlay: Heishi shōrin which according to one theory, represents [bǐng-zǐ], which is a stem-branch of the Sexagenary cycle and the author’s name: Shōrin. According to a document at Shitennō-ji, this sword was owned by Prince Shōtoku. Asuka period, 65.8 cm (25.9 in) Shitennō-ji, Osaka

2. Late Heian to Early Kamakura Periods

This shape represents the earliest curved Japanese swords. Long swords of this era are generally referred to as tachi. It is thought that the shift from straight blades to Japanese swords with curvature happened around the mid 10th to 11th century. Blades of this period are quite slender with the center of curvature concentrated between base of the blade the and the tang. This type of shape is called koshi-zori. They are shinogi-zukuri (ridgeline) in construction, wide at the base of the blade while noticeably narrowing towards the small point section (ko-kissaki).

From midway towards the point there is generally very little curvature. The average length of the cutting edge of blades of this period is usually around 75.8 cm-78.8 cm. Famous makers of blade with this type of curvature include Sanjo Munechika of Kyoto, who is known for his masterpiece, Mikazuki Munechika. Others include Tomonari, who along with Masatsune, are of the founders of the Ko-Bizen school of swordmaking, and Yasutsuna of Hoki province who is famous for the National Treasure sword, Doji-giri Yasutsuna, that was said to have been used by the warrior, Minamoto Yorimitsu to slay the Ogre Shuten-Doji of Mt. Oue. Both Munechika and Yasutsuna’s swords are included in the archaic list of the ‘Five Greatest Swords under Heaven’.

Changes in the Construction of the Japanese Sword Through History

3. Mid-Kamakura period

At the peak of the warrior class’s power during the Kamakura period, the blades become rather stout with a thicker (kasane) and slightly broader width, creating a magnificent tachi shape. There is not much difference between the width of the moto-haba and the saki-haba. The blades still have koshi-zori, but the center of the curvature has moved slightly further along the blade. The kissaki has become a compact stout chu-kissaki (ikubi: boar’s neck shape). The hamon has developed into a flowing gorgeous choji-midare. Around this time, tanto production also appears to become popular.

It is thought that the mongol invasions of 1274 and 1281 had an influence on not only the thickness of tachi, but also the manufacture of tanto due to the difficulty in cutting thick leather Mongol armor. The Japanese warriors took the battle back to the Mongol’s boats, fighting at close range utilizing the tanto. Famous smiths of this period include Nagamitsu from Osafune Village in Bizen province. Although Nagamitsu’s father, Mitsutada, is credited as the founder of the Osafune school, it is said that Nagamitsu systemized and proliferated the school.

4. Late Kamakura Period

Tachi at the end of the Kamakura period have developed into blades with magnificent shapes. There are two types: one style is wide throughout its length and the point section is similar to the mid- Kamakura period kissaki, but slightly extended. The other is quite slender and similar in appearance to the late Heian, early Kamakura shapes. However, when you look further along the blade, the center of curvature has moved slightly further up the blade.

5. Nanbokucho Period

For reasons that are unclear, many over-sized blades of 90.9cm and longer with large point sections (o-kissaki) were made during the Nanbokucho period. Large size tanto were also commonly produced. Among these were extremely long blades called o-dachi and no-dachi. To compensate for the extra length, blades of this period were rather thin in construction, or have a bo-hi (groove) cut into the shinogi-ji area to lighten the blade. However, as they were difficult to wield, many tachi from this period were shortened (o-suriage) to regular sword lengths in later periods. Consequently, many extant blades from the Nanbokucho period are unsigned due to being shortened. Additionally, during this period saw the birth of the Soden-Bizen style of workmanship. Bizen blades influenced by the swordsmiths of Sagami province (Soshu) began producing a hybrid style of the two traditions. Famous smiths producing this kind of work included, Kanemitsu and Chogi (Nagayoshi). The Soshu influence can also be seen in the work of Yamashiro smiths on the Rai school (Rai Kunimitsu, Rai Kunitsugu, and so forth).

6. Early Muromachi Period

Blades of the early part of the Muromachi period are reminiscent in shape to the blades of the early Kamakura period. Compared to the shape of Nanbokucho period blades, the design has completely changed and no longer includes o-kissaki. They are quite narrow and deeply curved with a medium-sized point section. The length of the cutting edge is generally between 72.7 cm and 75.7 cm. They may appear somewhat similar in shape to Kamakura period blades, but on closer inspection they display a somewhat saki-zori characteristic.

7. Late Muromachi Period

By the late Muromachi period, fighting methods had changed from cavalry to mass infantry style warfare. Shorter blades, known as uchigatana, with a cutting edge of around 63.6 cm in length that were intended for one-handed use became popular. As opposed to tachi that were worn suspended from the belt, uchigatana were worn thrust through the sash with the cutting edge uppermost. Following the Onin war, conflicts broke out in many places prompting the mass-production of blades (kazu-uchi-mono) that were inferior in quality to regular Japanese blades. However, specially ordered blades of excellent quality (chumon-uchi) were still also produced at this time. The provinces of Bizen (Okayama prefecture) and Mino (Gifu prefecture) became major places of production. Many blades produced in this period have a strong saki-zori, with either a chu-kissaki or an extended chu-kissaki.

8. Momoyama and Early Edo Periods

Swords produced up to the Keicho era (1596-1614) are classified as Koto (old-swords) Blades made during and after the Keicho era are classified as Shinto (new-swords). As peace began to spread throughout Japan during the Momoyama period, many smiths moved gathered in major cities, or castle towns of influential daimyo. Many blades from around this period tend to mirror the shape of that of shortened Nanbokucho blades with a large or extended medium sized point section. They have a cutting edge of around 72.7 cm to 75.8 cm in length. Unlike their shortened earlier counterparts, they retain the maker’s signature on the katana-omote and have a thicker kasane than Nanbokucho period blades. According to some documents, former samurai, Horikawa Kunihiro, is said the be the father of the Shinto era (new-sword). Originally from Hyuga province, he set up a forge in Horikawa, Kyoto. He produced several students that became masters of the Shinto era, but one of his own masterpieces is the utsushi-mono of Chogi’s Yamamba-giri (Yamamba-giri Kunihiro).

9. Edo Period; Kanbun Era

Swords of the Kanbun period have a noticeably shallow curvature. The saki-haba is relatively narrow when compared to the moto-haba, and have a medium-sized point section. They have an average cutting-edge length of around 69.7 cm. This particular type of construction is usually referred to as Kanbun Shinto and was generally produced around the middle of the Kanbun (1661-1673) and Enpo (1673-1681) eras.

Japan had been at peace for about 50 years, and in that time many Japanese fencing dojo had been established. It is thought that as Japanese swordplay moved into the dojo and became popular, that it affected the shape of the Japanese sword. Up to this point, deeply curved swords had been popular as they were extremely effective for slashing. However, deeply curved swords are also very difficult to fence and perform thrusting techniques with. As fencing tip to tip in the smaller confines of practice halls (as opposed to the battle field) grew in popularity, a shape of sword was produced that allowed swordsmen to utilize this way of fighting and use thrusting techniques proficiently. This was also a period in which dueling was not uncommon. Arguably the most famous smith of this period (and the Shinto swordmaking era) was Nagasone Okisato Nyudo Kotetsu, of who’s swords, Commander of the Shinsengumi, Kondo Isami, is said to have famously used in the Ikedaya Incident.

Nagasone Okisato Nyudo Kotetsu Wakizashi (ColBase https://colbase.nich.go.jp)

Commander of the Shinsengumi, Kondo Isami (国立国会図書館デジタルコレクションより)

10. Edo Period; Genroku Era

The change in shape of Japanese swords between the Jokyo (1684-1688) and Genroku (1688-1704) eras reflects the transition of shape from Kanbun-shinto blades to the beginning of the Shin-shinto (New new-sword) period of sword manufacture. As it was a very peaceful period in Japanese history, rather flamboyant hamon appear. In this era, there was a revival movement to recreate blades of older periods. Unlike the previous Kanbun era blades, the curvature once again becomes quite deep. The shape somewhat resembles that of tachi of earlier eras, but they are generally signed on the katana-omote. A pioneer of the movement was Suishinshi Masahide who was originally known for making utsushi-mono of early Shinto blades, such as Sukehiro, later advocated a renaissance to Koto (old-sword pre-1600) styles of swordmaking.

11. Edo period; Bakumatsu

Bakumatsu blades are shallow in curvature, have a thick kasane, a wide haba throughout, and an o-kissaki They generally have a cutting-edge length of 75.7cm-78.7 cm. The revival movement of making blades in other older shapes continues but the blades are thicker and heavier. Notable smiths include, Taikei Naotane (one of Suishinshi Masahide’s students), Koyama Munetsugu. Minamoto Kiyomaro also led a revival aimed at Soshu-den and Mino-Shizu workmanship. However, this period also saw the Boshin war where modern western artillery changed warfare methods completely, and ushered in the Meiji Restoration.

12. Meiji up to 1945

In 1876, Haitorei decree was issued banning civilians from wearing swords, resulting in a steep decline in the need for swords. However, in 1906 the swordsmiths Gassan Sadakazu and Miyamoto Kanenori were designated ‘Tei-shitsu Gigei-in’ (craftsmen by imperial appointment). Another resurgence of swordmaking took place from the 1930’s up until the end of the Second World War. From the 1930’s swords become slightly shorter at approximately 66 cm mostly aimed at military use. Many older swords were also adapted for military koshirae. Blades from this time until 1945 are currently referred to as kindaitō (early modern swords).

13. 1945 to Present Day

Following Japan’s defeat in the Second World War, sword making and martial arts were banned during the Allied Occupation of Japan. When sword making resumed in 1953, licensing systems for not only swords, but also swordsmiths was introduced. Today sword making is recognized as a traditional Japanese craft and continues to this day. Swords must be made using traditional methods from traditional materials, and be artistically engaging. Modern swordsmiths try to recreate works based on the workmanship of eminent smiths or schools of various historical periods, while at the same time exhibiting their own characteristics and originality.