Yoshida Shōin: Samurai Sage and the Noblest of Men

Yoshida Shōin was a man whose words and actions led to his own execution at the age of 29 in the Ansei Purge of 1859. Yet his teachings under house arrest at a small community school known as the Shōka Sonjuku produced men who would lead the Meiji Restoration just ten years later. There is something messianic about Yoshida Shōin, in his uncompromising, radical, and ultra nationalistic views. Even while he was imprisoned he could not be silenced. His students led Japan into the modern era, occupying some of the highest positions in the Meiji government.

Yoshida Shōin was a man whose words and actions led to his own execution at the age of 29 in the Ansei Purge of 1859. Yet his teachings under house arrest at a small community school known as the Shōka Sonjuku produced men who would lead the Meiji Restoration just ten years later. There is something messianic about Yoshida Shōin, in his uncompromising, radical, and ultra nationalistic views. Even while he was imprisoned he could not be silenced. His students led Japan into the modern era, occupying some of the highest positions in the Meiji government.

Born into the Chōshū Clan in Hagi, he graduated with Honors from the Meirinkan, the Chōshū Clan School. In view of his potential as a Samurai Scholar, the Clan authorities sent him on numerous educational journeys, over 11,000 kilometers on foot, bringing him into contact with the Sonnō Jōi movement to Revere the Emperor and Expel the Barbarians. That brought him directly into conflict with the Tokugawa Bakufu, or military government that had ruled Japan for two and a half centuries. He made friends and developed a following that crossed Clan boundaries, leaving over 800 letters to his followers, which clearly articulated his position on philosophical and political matters.

Ultimately he earned the wrath of Ii Naosuke, the high-ranking Tokugawa Official who was famous for signing the Harris Treaty for Amity and Commerce between the United States and Japan. As part of the Ansei Purge, Ii Naosuke put Yoshida Shōin on trial and ordered his execution.

Yoshida Shōin was a Scholar of the teachings of Yamaga Sokō (1622-85), an Aizu Samurai Scholar who encouraged both martial and intellectual training, as well as values now associated with Bushido: honor, moral leadership, duty, loyalty, and readiness to die for one’s lord. These values resonated with Yoshida Shōin. His messianic dedication and readiness to die for the cause later led to descriptions of Yoshida Shōin as a Samurai Christ.

A Man of Purpose

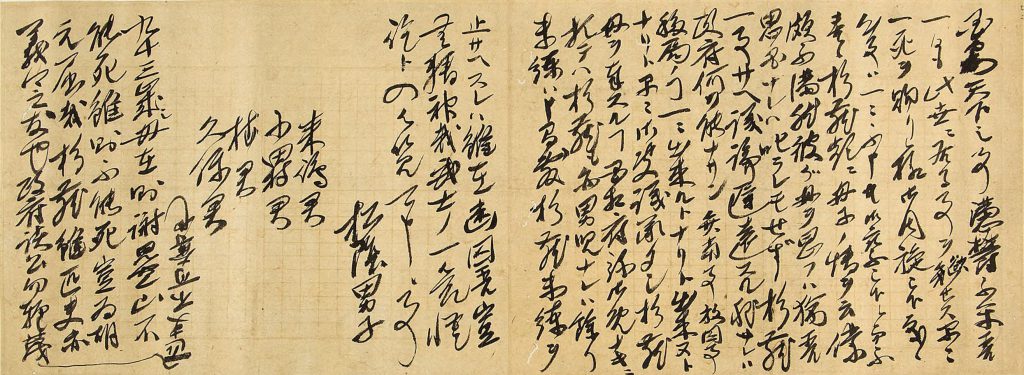

Yoshida Shōin wrote letters, journals, and political position papers, as well as poetry in the Kanbun or traditional Chinese style. While scholars have debated different aspects of his thought, teachings, and extensive writings, his brush writing leaves unmistakable traces of his personality. Shown here is his signature at the end of a letter he wrote in March of 1859, from the collection of Inoue Kaoru, a fellow Chōshū Samurai and a leader of the anti-foreigner movement, who later became the chief financial advisor to the new Meiji Government. In the heated controversy he demonstrated strong opposition to the signing of the Treaty for Amity and Commerce between the United States and the Empire of Japan. As a result, he was held in confinement at Hagi’s Noyama Prison.

This letter was written while in confinement, and addressed to fellow Chōshū Samurai, Kijima Matabei, Katori Motohiko, Kido Takayoshi, and Kubo Seitaro, all forerunners of the Meiji Restoration. The letter is a position paper opposing the Tokugawa Bakufu policy of Sankin-kōtai, the policy of required alternate attendance between Edo and the local domain, which strengthened central government control over local daimyo. In this letter he states his readiness to die for the cause of opposition.

Shōin’s signature reveals many aspects of his personality. The characters written here are 松陰男子, where Shōin has signed his name 松陰 (Shōin), followed by 男子 (danshi), meaning male. The first stroke is quite long, beginning well to the left of the character, the sign of a proactive leader, a man of wisdom and intelligence. However, in this case the horizontal stroke in his signature has an added nuance, because it slopes sharply up to the right, as do most of his horizontal strokes. The upward slant reflects his idealism, looking past the immediate reality and keeping his eyes on the Vision.

The space between the right and left radicals in both characters of his name is tightly held, but not entirely sealed off. A philosopher on a mission, he held strong beliefs, yet also curious to absorb and integrate knowledge from outside.

There is complexity in the mixture of rounded and angled corners. Rounded corners suggest his ability to bend and break the rules imposed on him, while angled corners show his strict adherence to internal principles.

Though sharply sloped, the horizontal lines are equally spaced, which shows a high degree of order in his thinking. The strokes are thin and tight, like a well-tuned stringed instrument, ready to perform and unafraid of action. The script is highly cursive and reminiscent of rapid speech, as if his brush could barely keep pace with his mind.

Lessons from Yoshida Shōin

Considering the unique and complex circumstances surrounding the life of Yoshida Shōin, as well as his messianic character, it might be difficult for us to draw immediate lessons from his life. Although even today to many he is a hero for his courage of convictions. His historical importance became apparent after he died, when his students played a pivotal role in the Meiji Restoration.

We gain a more personal view of his character through an unlikely biographer, Robert Louis Stevenson, who wrote a biographical sketch entitled Yoshida Torajirō (Shōin’s familiar name), based on the passionate account of one of Yoshida Shōin’s students, Taiso Masaki. Stevenson was so impressed with what he heard that he immortalized Yoshida Shōin in his biography of remarkable men, claiming that his name should be a household word.

http://digital.nls.uk/rlstevenson/browse/archive/90446010

Stevenson describes Shōin’s ill-fated attempt to board the ship of Commodore Perry in a plea to gain passage to America. To avoid a diplomatic incident, Shōin and his compatriot were not allowed aboard. They were returned to shore, where they faced certain imprisonment and possibly the death penalty for attempting to leave the country. Through this and other episodes, he describes a remarkable man who was so passionate about his country that he was nearly oblivious to his own fate.

Stevenson writes of Yoshida Shōin:

“His handwriting was exceptionally villainous; poet though he was, he had no taste for what was elegant; and in a country where to write beautifully was not the mark of a scrivener but an admired accomplishment for gentlemen, he suffered his letters to be jolted out of him by the press of matter and the heat of his convictions.”

Here you see the quality of Yoshida Shōin’s charisma, character and convictions outshining any regard for compromise or convention. He explains how scholars over time shifted their perception of Yoshida Shōin from that of a comic schoolmaster, to that of the noblest of mankind.

William Reed is from the USA, but is a long-time resident of Japan. Currently a professor at Yamanashi Gakuin University, in the International College of Liberal Arts (iCLA), where he is also a Co-Director of Japan Studies. As a Calligrapher, he holds a 10th-dan in Shodo from the Nihon Kyoiku Shodo Renmei, and is also a Certified Graphology Adviser from the Japan Graphologist Association. As a Martial Artist, he holds an 8th-dan in Aikido from the Aikido Yuishinkai. He holds a Tokubetsu Shihan rank in Nanba, the Art of Physical Finesse. A weekly television commentator for Yamanashi Broadcasting, he also has appeared numerous times on NHK World Journeys in Japan, and in documentaries as a navigator on traditional Japanese history and culture. He has appeared twice on TEDx Stages in Japan and Norway, and has written a bestseller in Japanese on World Class Speaking.

William Reed is from the USA, but is a long-time resident of Japan. Currently a professor at Yamanashi Gakuin University, in the International College of Liberal Arts (iCLA), where he is also a Co-Director of Japan Studies. As a Calligrapher, he holds a 10th-dan in Shodo from the Nihon Kyoiku Shodo Renmei, and is also a Certified Graphology Adviser from the Japan Graphologist Association. As a Martial Artist, he holds an 8th-dan in Aikido from the Aikido Yuishinkai. He holds a Tokubetsu Shihan rank in Nanba, the Art of Physical Finesse. A weekly television commentator for Yamanashi Broadcasting, he also has appeared numerous times on NHK World Journeys in Japan, and in documentaries as a navigator on traditional Japanese history and culture. He has appeared twice on TEDx Stages in Japan and Norway, and has written a bestseller in Japanese on World Class Speaking.