Many martial arts masters in the past have also been masters of the brush. The sword speaks to the brush, and the brush instructs the sword. With Mastery they become one. William Reed has a 10th-dan in Shodo and an 8th-dan in Aikido, and in this Series he looks at the human character behind the written character in Samurai Shodo. In the 9th article of this Series he paints and analyzes the brush writing of Sen no Rikyū, Samurai Tea Master of the Sengoku Period, who established the fundamentals of the Japanese Tea Ceremony as we know it today.

Written by William Reed

Professor at Yamanashi Gakuin University

10th-dan in Shodo and Vice-Chairman of the Nihon Kyoiku Shodo Renmei

8th-dan in Yuishinkai Aikido

Editorial Layout by Gekkan Hiden Editorial Staff

Handwriting analysis supervised by Ishizaki Senu, Certified Graphologist by the Japan Graphologist Association

The Brush is the Sword of the Mind

Reading the Character Behind the Brush Strokes

Spirit of the Samurai

Sen no Rikyū, known as the Saint of Tea, was the Founder of the Senke School of the Tea Ceremony.

The Greatest Tea Master under Heaven who Perfected the Art of Wabi Cha

Sen no Rikyū (1522~1591) was born in Osaka as the oldest son of a Sakai Fishmonger Family known as Totoya. His given name as a child was Kōshirō, and his posthumous Buddhist name is Sōeki. The special name Rikyū was granted to him by the Ōgimachi Emperor when Toyotomi Hideyoshi was Chief Advisor to the Emperor, in return for the favor of Serving Tea at the Highly Exclusive Imperial Tea Ceremony, another reason being that he would not be permitted inside the Imperial Palace while bearing the name of a commoner. It was the name Rikyū by which he became widely known as the Greatest Tea Master under Heaven. Rikyū was 63 years old at the time.

Sen no Rikyū (1522~1591) was born in Osaka as the oldest son of a Sakai Fishmonger Family known as Totoya. His given name as a child was Kōshirō, and his posthumous Buddhist name is Sōeki. The special name Rikyū was granted to him by the Ōgimachi Emperor when Toyotomi Hideyoshi was Chief Advisor to the Emperor, in return for the favor of Serving Tea at the Highly Exclusive Imperial Tea Ceremony, another reason being that he would not be permitted inside the Imperial Palace while bearing the name of a commoner. It was the name Rikyū by which he became widely known as the Greatest Tea Master under Heaven. Rikyū was 63 years old at the time.

Rikyū entered the Path of Tea at the age of 16. His Teacher was Master Jōō (1502–1555), who was a student of the Founder of the Tea Ceremony Master Jukō (1423–1502), who originated the concept of Wabi Cha (Tea served in sober refinement), that was perfected in the 3rd generation by Rikyū.

The practice of the Tea Ceremony began in the Nara Period (AD 710 to 794) and Heian Period (794 to 1185), when Cultural Envoys and Buddhist Priests traveled to China on Missions of Study and Cultural Exchange bringing Buddhist Culture to Japan. In the early Muromachi Period (1336 to 1573), vast sums of money were spent on bringing Treasures of the Tea Ceremony to Japan, and this helped establish the rich heritage of the Japanese Tea Ceremony.

Jukō was a disciple of Zen Master Ikkyū (1394–1481), and Jukō established the Tea Ceremony as a Path for Spiritual Development, placing great emphasis on the importance of the Spirit of the person in full engagement in the process of preparing Tea. This was a worldview which became expressed by the proverb “The Taste of Tea is the Taste of Zen” (Cha-Zen Ichi-Mi). Jōō built on Jukō’s aesthetic of Wabi as sober refinement, and integrated even further ideas from Zen into the aesthetics of the Tea Ceremony, such as mature withering (kareru), and the beauty of imperfection (fusoku no bi). These ideas contributed to spiritual wholeness through the minimalist aesthetic of Cha no Yū, also known as Sadō, the Way of Tea.

Rikyū said that he learned the skills and techniques of the Tea Ceremony from Jōō, but the Way of Tea from Jukō. But Rikyū made his own contribution by deepening the teachings of his own Masters, perfecting the manners and etiquette (sahō), establishing rules for construction of the Tea Room (cha shitsu), formalizing the Tea Ceremony as a practice, and perfecting the performance of Wabi Cha.

Caught in the Narrow Space between Sado and Samurai Politics

Rikyū had the misfortune of being caught between the demands of refining the Way of Tea that he had learned from his two spiritual masters Jōō and Jukō, and of complying to the demands of his two secular masters Oda Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi, the latter of which manipulated Rikyū for his own purposes.

The Sakai area of Osaka was a center for the Nanban Trade with South Sea Countries. It was the Merchants of Sakai who helped procure and sell rifles and other weapons, and they were also involved in the first domestic production of such weapons. The atmosphere of free trade in this area promoted the exchange not only of goods, but of people, culture, and ideas.

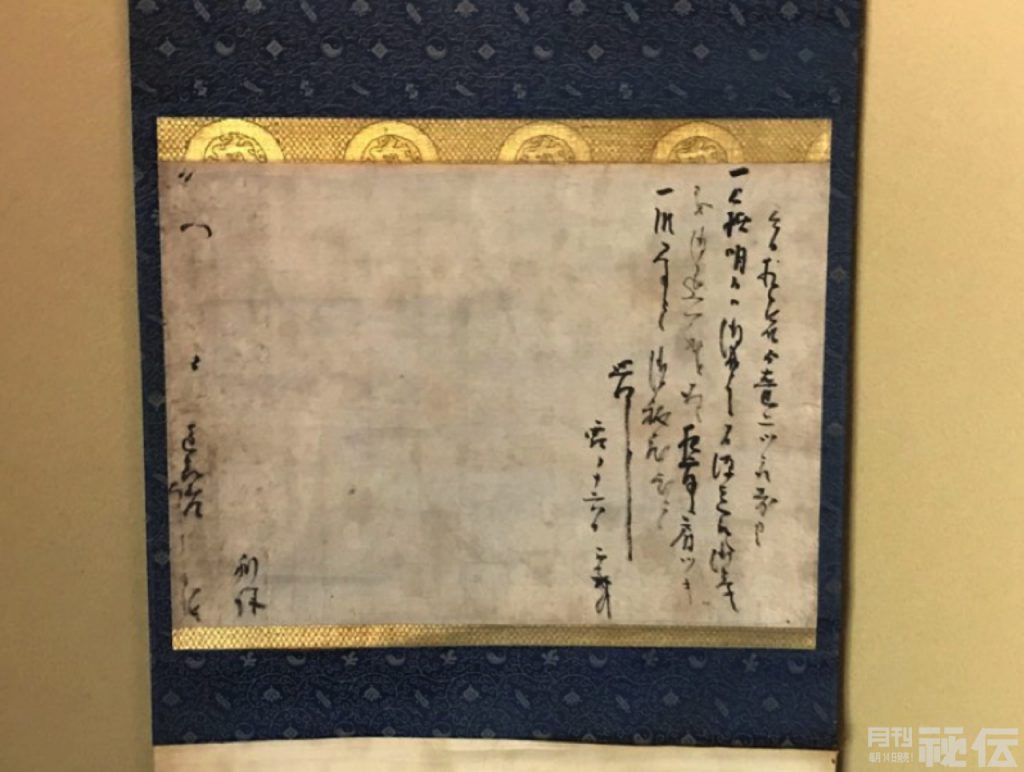

This is a letter written by Sen no Rikyū, which is part of the Erinji Temple Collection. It reflects his skill and dexterity as well as his strength of spirit.

This is a letter written by Sen no Rikyū, which is part of the Erinji Temple Collection. It reflects his skill and dexterity as well as his strength of spirit.

The first of the Sengoku Warlords who attempted to unify the country under his command was Oda Nobunaga, and he was not blind to the potential of controlling an area like Sakai, with its vast wealth, power, and international connections. He wanted to control it to gain access to funds for his military ventures, as well as to a steady supply of weapons.

He forcibly collected or demanded to purchase many valuable Tea implements, and once added to his collection used them to reward those of his retainers who performed valiantly on his behalf, so that his valuable collection of Tea Treasures became a political treasury. After Nobunaga, Hideyoshi carried on in this relentless accumulation of Tea Treasures, while he also dedicated himself to studying the Art of Tea. The Samurai valued these treasures both as forms of wealth and status. Hideyoshi appointed Rikyū as his Tea Ceremony Teacher, and used him to assist in what was termed by author Morgan Pitelka in his informative book as, Spectacular Accumulation.

However, much of Oda Nobunaga’s spectacular collection perished along with Nobunaga in the Honnō-ji Incident in 1582, when Nobunaga was betrayed by his Samurai general Akechi Mitsuhide, and the collection was reduced to dust in the flames. Hideyoshi then took power, and became even more dedicated to the Tea Ceremony and the collection of Tea Treasures, employing Rikyū in the process, and holding large-scale Tea Ceremonies. Not only was Rikyū named to conduct the Imperial Tea Ceremony for the Emperor, but also to conduct a Grand Tea Ceremony at Kitano Tenmangū Shrine to flaunt and display the power of his secular master. To this Grand Event were invited not only Public Officials and Samurai, but also Farmers and Townspeople were allowed to participate. Tea was served by the Master Hosts, the three Tea Masters of the time, Imai Sōkyū, Tsuda Sōkyū, and Sen no Rikyū, and even by Hideyoshi himself.

However, there were irreconcilable differences in the worldview and values which Rikyū sought to establish in the solemn refinement of Wabi Cha, and which Hideyoshi sought to flaunt in ostentatious display such as Gold-Plated Tea Rooms. The gap which separated these two men over such differences only served to widen from that time. Rikyū detested garish display and ostentatious performances in the Tea Ceremony. He even criticized Tea Masters who attempted to show off their display of Wabi. How must he have felt at being forced to serve Tea in a gilded chamber?

At the same time, Rikyū was the only person who Hideyoshi could not force to comply with his strong Will and every whim. Rikyū was a man who could see things with the Mind’s Eye, and appreciate them in Silence. By contrast, Hideyoshi was talkative and loud-mouthed in his opinions. Hideyoshi was infuriated by Rikyū’s capacity to solve problems of all kinds with his resourceful mind. Reading stories of interaction between the two men, you can almost hear the gnashing of teeth in Hideyoshi’s love and hatred of Rikyū.

Reading the Character from the Brush Strokes

Take a close look at the letter shown here written by Rikyū. This masterpiece is part of the collection of Erinji Temple, located in Kōshū City in Yamanashi Prefecture, a Rinzai Zen Temple with the full name of Myōshinjiha Kentokusan Erinji.

Note how the vertical columns of characters tend to drift to the left toward the bottom of the column, yet is drawn back toward the center line of the column at the base. In vertical column writing, the tendency to drift to the left in the direction of the future is a reflection of an optimistic temperament, while the effort to pull back toward the center would seem to be an effort to hold such feelings in check. This is not surprising considering the intense pressure he was under to go against his own deepest values. This was likely an unconscious effort to keep his own balance and maintain his sanity under such circumstances. For Rikyū, the pull of his own deep commitment to the Way of Tea was being pulled in the opposite direction by the harsh political motivations of Hideyoshi. Rikyū had mastered the Way of Tea to a level of Genius that was almost beyond the grasp of ordinary men, yet he found himself in a world pulling him in the opposite direction. You can feel the tension in the vertical line attempting to rein itself back to the center line.

The left and right-hand radicals of many of Rikyū’s characters are closely held, with not much space in between. There are even instances where the internal spaces of the characters has collapsed under a tightly held hand. These characteristics are often found in Artists who hone their craft to a high level, and it reflects the mental and spiritual tension inside which often drives their artistic achievement to a high level of expression. This can be seen in the brush writing of Rikyū.

His writing reflects both high sensibilities and a strength of spirit. He must have had many opportunities to compromise and comply with Hideyoshi’s demands, which would have saved his life. However, in the end he chose the Way of Tea without compromise, remaining on his chosen Path, and refusing to compromise to the demands of authority. This culminated in a series of incidents which led Hideyoshi to demand that Rikyū commit forced suicide (seppuku), when the wounded pride of Hideyoshi the secular master clashed with the uncompromising pride of Rikyū the spiritual master.

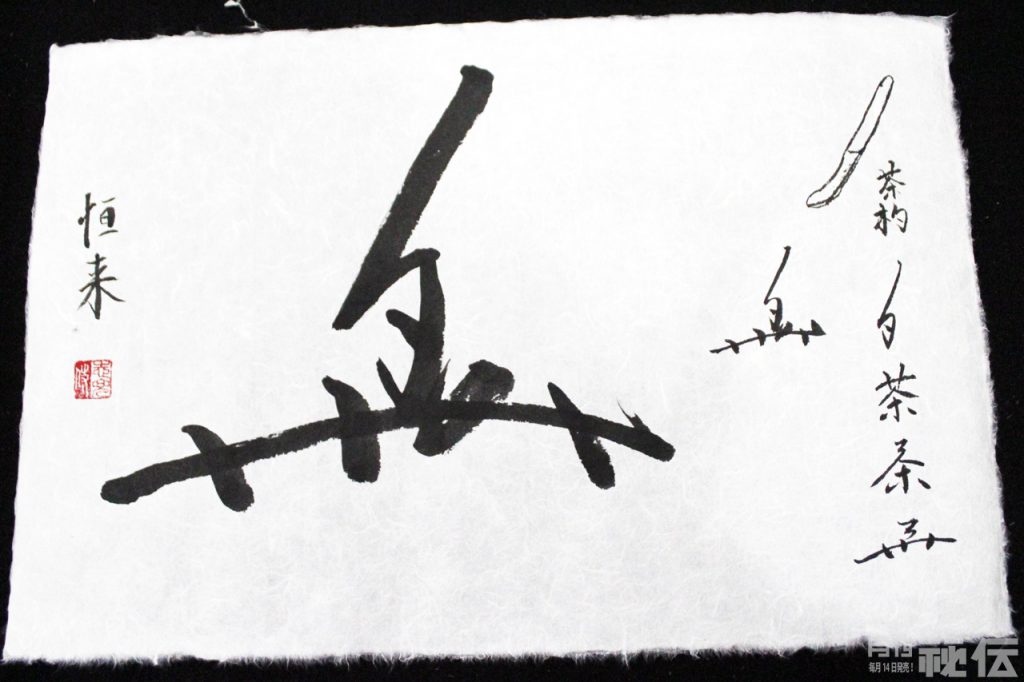

According to the book by Shimizu Kenseki, Encyclopedia of Samurai Signatures (Kaō wo Yomitoki Ko Jiten), Rikyū’s Samurai Signature was a composite design blending the elements of Sen 千 and Cha 茶 from his name and his profession, into an elegant and surprisingly modern design. The first stroke of the character for 千 is written in an extended manner, to resemble the Tea Spoon (cha-shaku) used to dispense Matcha Tea Powder into the Tea Bowl. I have painted a copy and explanation of Rikyū’s Samurai Signature in the photo and Video. This wonderful and imaginative way to design a Signature is surely a measure of the Master himself.

Rikyū’s Samurai Signature was a composite design blending the elements of Sen 千 and Cha 茶 from his name and his profession, into an elegant and surprisingly modern design.

Rikyū’s Samurai Signature was a composite design blending the elements of Sen 千 and Cha 茶 from his name and his profession, into an elegant and surprisingly modern design.

* Note that the Calligraphy by Sen no Rikyu featured in this article is on display at Erinji Temple in the Erinji Teasure Exhibition, which also includes calligraphy by Takuan Sōhō, on display until April 30, 2019.

William Reed is from the USA, but is a long-time resident of Japan. Currently a professor at Yamanashi Gakuin University, in the International College of Liberal Arts (iCLA), where he is also a Co-Director of Japan Studies. As a Calligrapher, he holds a 10th-dan in Shodo and is Vice-Chairman of the Nihon Kyoiku Shodo Renmei, and is also a Certified Graphology Adviser from the Japan Graphologist Association. As a Martial Artist, he holds an 8th-dan in Aikido from the Aikido Yuishinkai. He holds a Tokubetsu Shihan rank in Nanba, the Art of Physical Finesse. A weekly television commentator for Yamanashi Broadcasting, he also has appeared numerous times on NHK World Journeys in Japan, and in documentaries as a navigator on traditional Japanese history and culture. He has appeared twice on TEDx Stages in Japan and Norway, and has written a bestseller in Japanese on World Class Speaking.For other articles in the Series, visit http://www.samurai-walk.com/samurai-shodo