text by Satoshi Taito, translation by Lionel Lebigot

What about the “kama no te” of the Kingai-ryû-Okinawa kobujutsu presented below? The trading kingdom of Ryûkyû combined the fighting techniques of Japan and China to give birth to its own fighting art. Hayasaka Yoshifumi shihan reveals “the art of Ryûkyû’s sickle”

Kama-jutsu of the Ryûkyû Kingdom

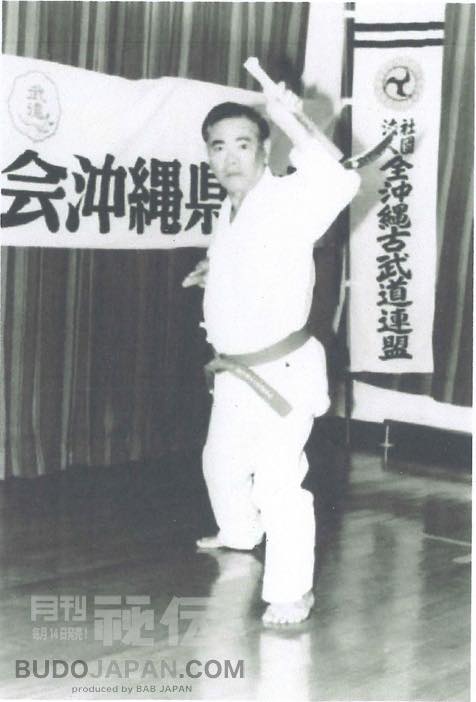

Kamanutî by Matayoshi Shinpô.

The art of sickle transmitted in the Ryûkyû kobudô is called “Kamanuti”. The technique consists of striking the four members in cut and thrust. A fighting art transmitted from China to the warrior families of Ryûkyû, together with the tûdî (karate), it has evolved to reach its own identity.

“In the family of Ryûkyû’s fighting techniques, these those who use Japanese weapons are pronounced [-no te], while the techniques transmitted from mainland China are pronounced in Fujiano-Okinawan [-nu tî], so [kuwa no te] (hoe), [kama no te] (sickles), [kai no te] (oar) are considered Japanese.” explains Hayasaka Yoshifumi shihan.

Hayasaka-shihan studied under Matayoshi Shinpô sensei, the 16th generation of the Kingai-ryû style, who awarded him a menkyo-kaiden (full transmission diploma) in kingai-ryû tûdî (karate) and Okinawa kobujutsu. The handling of kama uses the body technique of the Southern Shaolin. This Chinese fighting technique introduced to the Ryûkyû Kingdom sublimated indigenous fighting art under the name “tûdî.”

The prosperity of the Ryûkyû Kingdom dates back to 1429. At that time, and for lack of iron ore, Ryûkyû used little ironwork, so sickles and hoes were not massively introduced until after the invasion of Satsuma in the 17th century

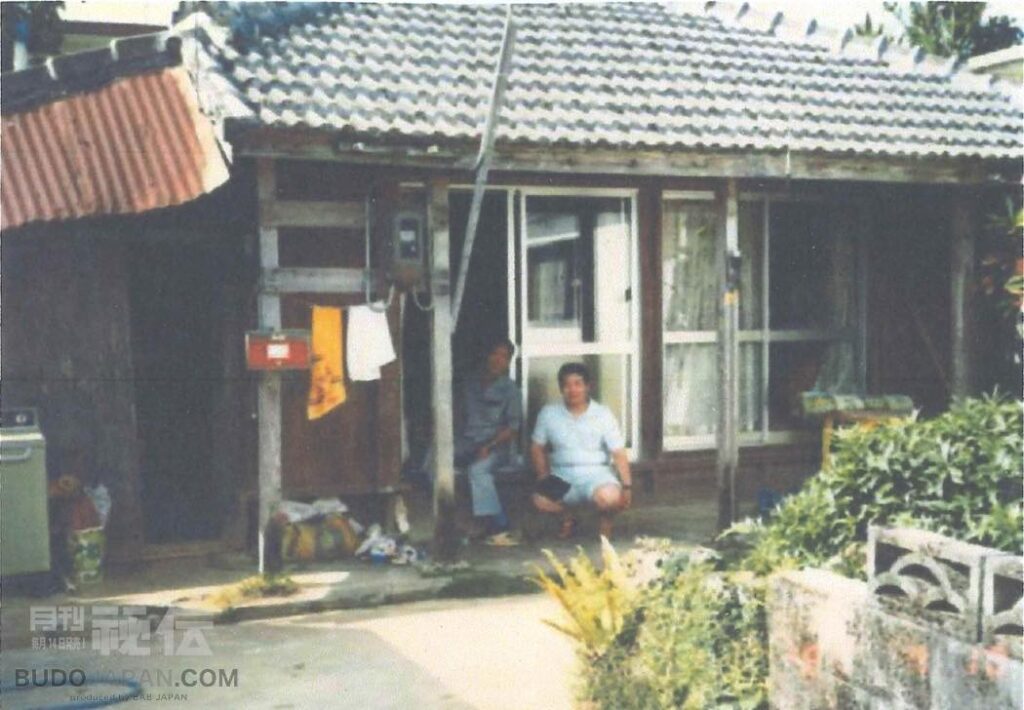

Matayoshi Shinpô (left) and Hayasaka Yoshifumi (right) visiting genealogical studies at the home of a descendant of Agena Naokata.

Matayoshi Shinpô (left) and Hayasaka Yoshifumi (right) visiting genealogical studies at the home of a descendant of Agena Naokata.Within the Satsuma clan, the samurai studied Jigen-ryû kenjutsu or Yakumaru-kenjutsu, Yôshin-ryû jûjutsu, and Ten-ryû bôjutsu and naginatajutsu. These fighting arts were also studied by Ryûkyû warriors (busâ) at an establishment called Ryûkyûkan in Kagoshima, the “capital” of the Satsuma Domain. Legend has it that during the assaults/exchanges, Ryûkyû’s warriors were stronger than the Satsuma warriors and that the famous Matsumura Sôkon was never defeated by one of Satsuma’s samurai.

Although Ryûkyû was annexed to the Feudal Satsuma clan, he received Chinese envoys (sappû) from the Ming and Qing dynasties, and in the eyes of these envoys, “the kingdom” remained an independent trading nation. The same goes for the combat arts: a unique creation from Chinese and Japanese contributions.

Kama of the Matayoshi family tradition

The Matayoshi family, a family of men-at-arms from the Kingdom of Ryûkyû, dates back to the great ancestor Shinbu. As long as she was heir to the combat arts, the family was versed in the trade with China of the Ming and Qing dynasties. Agena Naokata, a man-at-arms from Gushikawa village and friend of Matayoshi Shinchin, 14th heir to the family’s martial tradition, had a great influence on the young Matayoshi Shinkô. Naokata was born in 1859. He was in charge of the management of the criminal affairs of his region, then in charge of missions to King Shô Tai. Naokata was an expert in the handling of oars, kamas, bô, and nagagama. The young Shinkô deepens his practice of bô, eku, kama and sai. All techniques he transmitted to his son Shinpô.

The kamanutî of the Matayoshi family includes a wide variety of kama: nichôgama (double sickles),Ittôgama (short-stem sickle), nichô-suruchin (double sickles with rope), himotsuki-icchôgama (simple sickle with rope), suruchingama (sickle with rope), Nagagama (fauchard),Tsukigama (half-moon sickle),etc. and each has its own theory and technique. In Okinawan, the kama used in an agricultural context, takes the name “irarâ” in a martial context, the Japanese name “kama” is used. It is said that in expert hands, a kama bearer can face a swordsman, the latter would even have many difficulties.

Hayasaka-shihan showed us the Ryûkyû kamanutî.

nagagama, ittôgama, nichôgama

surûchingama, himotsukigama, himotsukinichôgama

The use of the principles of the sublime tûdî kamanutî

From the beginning of the learning, one learns to handle a pair of kama. One kama in each hand, alternately, right kama and left kama serve in attack or defense. The same goes for kenjutsu when using two swords, it requires precise physical coordination. In kama nu tî, we use the body principles of the tûdî, one kama attack, the other pare.

The angle between the blade and the sickle handle is 90 degrees, but either by tilting a kama or by combining the two weapons, the angle can be changed to 30, 45 and 60 degrees, which optimizes the cuts of hands, feet, neck and body. For example, on an attack, receive the attack with the handle of the left kama and attack the opponent’s neck with the right kama. In another case, the two kama, lined up at 180pariing the opponent’s bô, then the two blades shear the stick. The left kama lowers the bô, the right kama, can, for example, sting in the region of the jugular vein.

The two kama seize the attack, demeans it…

… the left kama goes down…

… the right kama attacks the opponent’s neck.

In the case of a short-range attack, the kama is held along the forearm (gyaku-te), in an elbow movement, the blade counterattacks the opponent’s flank. Countering, the left kama is seized along the forearm, adorns the attack, then after a slight shift, followed by a step, in an elbow movement, the right kama sinks into the torso of the attacker. The attacks and counter-attacks of elbows develop extreme power, reinforced by the blade of a kama, they become devastating.

“It’s important to practice alternating grips so you can change smoothly at any time. Changing the grip to attack and defend at will, this is Nichôgama’s ultimate. »

Countering, the left kama is seized in gyaku-te, adorns the attack, then after a slight shift, followed by a step…

In an elbow movement, the right kama sinks into the attacker’s torso.

The blade bites so deeply that the stick could break to the next attack or parade.

“Slicing the Net” and Chinkuchi

echnic of the Ryûkyû’s Warriors to escape from a net. Legend has it that this technique was developed by Ryûkyû’s warriors in battles against the samurai of Satsuma at the time of the invasion of the kingdom. The technique consists of inserting the blade of the kama into the mesh of the net and splitting them.

[Escape from the net]

Cut the net.

the kama slip under the net and reject it to free.

In the assaults with nichôgama, the kama pare and hit quite harshly the attacks of bô or bokken, one would then think that some strength is necessary. Yet, by judiciously using the bodily principles of tûdî , gamaku and chinkuchi, the actions of the body require no strength.

In the kama slice technique, we observe two techniques: mawashi-giri and kake-giri (twiring and vertical cut.) For mawashi-giri, the sickle is turned above the head, it impacts the neck, then, the kama is pulled to slice, that is when the chinkuchi is put into action during the retraction of the arm that holds the kama. This linear retraction slices net target. The kama is not driven by the force of the arm alone, but by the whole body, using chinkuchi. The cut has, instantly, great power. In the case of the ascending cut, the kama slices from the bottom to the front and the top. Also in this technique, when cutting, the chinkuchi must be implemented and the whole body must be used to slice and shoot in the same movement. The blade of the kama stab at the low level, makes them make a pivot and shoot, causing the opponent a fatal injury. The striking of the elbow with a kama is also a characteristic technique. Put the kama into gyaku-te (handle along the forearm) after hitting the opponent with his end, raise the hand up as if to hit the elbow, and the blade will slice from the bottom up. In close combat, in ascending cuts, the use of chinkuchi is a plus, not insignificant.

“If you don’t use chinkuchi correctly, your body won’t turn enough. Not only will the potential of kama not be fully exploited, but you risk cutting yourself. Whether the cut is from the outside to the inside, from the inside to the outside, from the bottom to the top, from the top to the bottom, you must train your dexterity to change grip easily.” Hayasaka-shihan insists on using the body by applying the principles of tûdî.

[mawashi-kiri] The kama rotates above the head, cut using the chinkuchi

[kake-kiri] As with a karate tsuki, starting from the waist or pectoral, hit with the back of the blade, turn and cut.

[kake-kiri] As with a karate tsuki, starting from the waist or pectoral, hit with the back of the blade, turn and cut.

Weapon Kama: stone and rope

Nichôgama uses two sickles, initially intended for agricultural work, there are other kama: nagagama, long-handled kama and kama (single or double) with rope or not.

Himo-tsuki-nichôgama and himo-tsukigama are weapon kama tied with ropes. The rope, braided with fibers of a kind of palm tree (shuro) is oiled and is wrapped around your hand. It is said that the oiled fibers of this rope are sufficiently reinforced so that they cannot be cut by a blade. When you practice by grasping the handle, the practice does not change, on the other hand, if you let the rope run, the length allows you to reach a distant opponent. There is also a technique where you spin the kama like a nunchaku. In this technique, when the rope wraps around your body, the use of gamaku combined with a slight change in body position means that the kama blade does not strike.

To ensure that the rope does not come off if the palm is open, it is specifically wound into the palm. Moreover, opening and closing the hand allows the length of the string to be changed quickly and the opponent cannot appreciate the distance.

There are two types: kama whose rope is attached under the blade (pictured above) and a kama whose rope is tied attached to the end of the handle.

The rope is wrapped around the hand in a specific way.

By opening, closing hands, you can change the length of the rope.

Surûchingama

Surûchingama, connects a stone to a kama by means of the oiled rope made of shuro fibers. The surûchin is a primitive weapon made of stones bound by a rope. Originally, surûchin would have been a hunting tool. The technique consisted of twirling the weighted rope over the head, throwing, the stones would get in the way of the animal’s legs. Surûchingama is very similar to the Japanese kusarigama. The stone can be thrown with the right hand, the left hand slices the kama held in the left hand.

If you twist the weighted rope with your right hand, let the rope spin, which will eventually wrap around the target and then slice with the kama. With a well-proportioned manipulation of the rope, lengthening or shortening it, the opponent will not be able to determine whether he will be attacked by the stone or the kama.

Wrap the rope, kama side around the opponent’s neck.

Conversely, the stone wraps around the leg.

pare the bô with the kama held by the left hand

Hit with the stone in your right hand.

Japanese influences on nagagama

Nagagama

Nagagama is said to have originated from an agricultural tool originally intended for mowing grass. The long handle allows large circular movements, as with a naginata. In its technical specificity, the nagagama is handled close to the body, with undulating movements of the body, the strikes and cuts are sharp and at short distances, it is an effective weapon both in attack and defense. The kama of this weapon is wider than nichôgama and at the base of its backhand there is a protuberance. The role of this protuberance is to hook the opponent’s weapon, to destabilize the wearer by pulling it, and then, after rotating the hand, to cut with the blade. The practice of the Okinawan nagagagama is very close to that of the Japanese naginata.

The attack is received with the protrusion

The protrusion skewers the attack.

Destabilize the opponent and counter-attack.

Ittôgama is another form of kama, equipped with a handle of about 1m30cm and a blade similar to the basic kama. Very similar to Japanese nagamaki, ittôgama is used in the same way. In practice, ittôgama is wielded along the body, dodge the attack and counterattack briskly.

Hold ittôgama with both hands and intercept the attack with the left hand,

dodge and counter-attack.

After dodging, ittôgama stings the top of the skull.

The fluidity of tûdî enhances the handling of ittôgama In practice, grasp ittôgama with both hands, intercept the attack and dodge to the left, counter-attack. The movement of the elbows towards the left and the right makes it possible to link the defence and the attack. Attack and defence must be quickly linked. The deepening of the elbow techniques of tûdî greatly helps the offensive and defensive techniques of ittôgama..

Above, performance of a kata.

Mikazuki-kama (chichigama in Okinawan) is a kama whose blade in the shape of a crescent moon, the same weapon is found in Chinese fighting arts. Originally, this tool would have been used to prune trees. The chichigama blade can intercept the opponent’s weapon, destabilize it, and then snuck, cutting arm, leg or neck. The influence of Japanese fencing with spear or long sword is easy to see.

Interception of a low attack of the opponent is stopped in the tips of chichigama,

thrust at the neck.

Particularities

Originally an agricultural tool, Chinese and Japanese influences, made the Okinawan Irarâ, a weapon kama with formidable efficiency ,if any, at the height of the weapons of these two powerful lands. Moreover, combined with the fluidity of the tûdî, kama has its own Okinawan identity.

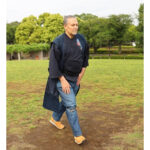

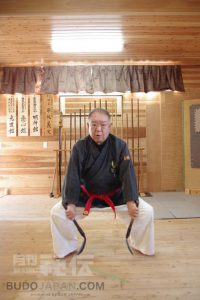

Hayasaka Yoshifumi –

Hayasaka Yoshifumi –