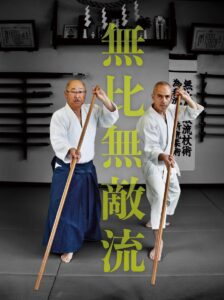

Muhi Muteki-ryu: Mito’s untamed spirit

Text by Grigoris Miliaresis

There are many schools that make an impression when you first attend a major demonstration at Meiji Jingu or the Nippon Budokan: most people never forget the first time they saw the majestic movements of Ogasawara-ryu, or the clashing armors of Yagyu Shingan-ryu or heard the thundering fusillades of Morishige-ryu. For me though, it was another school that did it: three pairs of practitioners with hiked-up momodachi-style hakama, a white hachimaki around their heads, armed with a bo and a heavy bokuto furnished with a double huge tsuba engaged in what looked and felt like real fight with roaring kiai, formidable strikes and a hairbreadth sense of distancing. Its name was Muhi Muteki-ryu and my instinctive reaction was “this isn’t samurai budo: this is commoners’ self defense –and I need to see it from up close!”

Meibukan: A family affair

The time is a Sunday morning ten years later and the place is Ibaraki’s Hitachinaka, about 800m/half a mile from the beach. The streets are empty and every few blocks you see ads for restaurants serving kaisen don (seafood on a bowl of rice) –commercial fishing is a big part of Hitachinaka’s economy. The one-storey house we stop our car in front of, is architecturally nondescript but it stands out because in front of it is a small Inari shrine accompanied by a big black stone monument giving passersby a brief history of Muhi Muteki-ryu Jojutsu and Iga-ryu-ha Katsushin-ryu Jujutsu. The house itself has a wooden sign that says it is the Meibukan of the two arts which are designated intangible cultural assets of Hitachinaka and an unassuming smiling middle-aged gentleman comes to greet us: he is Nemoto Kenichi, the 15th soke of Muhi Muteki-ryu.

Hiraiso beach

The wooden sign of Meibukan dojo

Inari shrine and stone monument

Nemoto soke carries the weight of 400 years of history with admirable ease: his family has been heading the tradition for three generations so when he speaks about its history it is essentially the history of his family and the pictures on the walls of the dojo as well as in the big rolls of cardboard he pulls out to show us, are filled with childhood memories that for him go back 50 years ago, before 1978 when present-day Meibukan was built by his father and 14th soke, Nemoto Heizaburo, as a way for more people of the area to practice the art. This is perhaps the reason that while he comprehends perfectly his art’s importance and the enormity of the task of continuing it, he only refers to himself as just one point in its flow. Or the reason that the moment he lays his hands on the bo (which Muhi Muteki-ryu calls a “jo” even though it is 5 shaku 5 sun i.e. 166 cm/5.5 ft) or the bokuto with the huge tsuba (which is double: one round wooden layer and one square rawhide layer to protect the wood from the jo’s ferocious strikes) it is with the effortlessness regular people hold a pen or a pair of chopsticks –and with the same efficiency.

14th soke, Nemoto Heizaburo

Kunii Zenya (Kashima Shin-ryu 18th Soke)

Nemoto Kenichi soke with Muhi Muteki-ryu photos

A broken spear and a doorstop bar

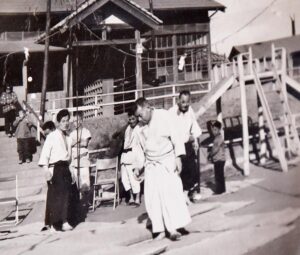

Dedication of a plaque by Muhi Muteki-ryu to the Sakatsura Isosaki Shrine in 1953.

Soke’s narration of the tradition’s history confirmed my initial impression: Muhi Muteki-ryu was a commoners’ and a farmers’ art of survival: while the story goes that its founder, Sasaki Tessai Norihisa fought in the battle of Sekigahara and having his spear broken, improvised the rest of his fight with the haft thus getting the inspiration for a method of fighting using just the stick, the school was mostly developed in the early Edo Period, utilizing everyday items including door stop bars, as a way for Mito Domain commoners to defend themselves against violent ronin and martial artists who would wander around the broader Kashima-Katori area for their musha shugyo. And between accounts from those times where (then) Muhi-ryu is frequently mentioned as a force to be reckoned with and its proliferation all over the domain there is little doubt of its effectiveness as a method of self defense against those thugs. Mito people where notorious for being rough and the people of Hiraiso coast, the area close to the Meibukan, even more so and this might explain why the school took root there.

Not that anyone would need to rely on old stories, though: as I wrote above, present-day Muhi Muteki-ryu is without a doubt one of the most vibrant classical martial traditions of Japan. Its intensity often hides the fact that there is a lot of sophistication in the handling of the jo against the long sword, the paired short and long swords and the spear and its strategy of relentless succession of attacking techniques while opening and closing the distance, setting baits for the opponent and exploiting them and interchanging between striking and thrusting, covers a wide variety of possible exchanges between the weapons; at the same time, and like all well-thought fighting systems, there are some basic elements like the 丁-shaped positioning of the feet, the low stances, the Honuchi and Gyakuuchi grasping of the jo, the Yumihari diagonal readiness kamae and the twirling change of sides that are used throughout its curriculum and allow for the development of a set of reflexes that will allow the practitioner to respond to any eventuality.

Nemoto soke’s demo 1

Nemoto soke’s demo 2

Nemoto soke’s demo 3

Nemoto soke’s demo 4

Nemoto soke’s demo 5

Nemoto soke’s demo 6

Nemoto soke’s demo 7

Nemoto soke’s demo 8

Our talk with Nemoto soke was cut short by the arrival of the Meibukan members. Some already dressed for practice, and some in their street clothes, some from the area and some from as far as Tokyo, some as young as in their early 20s and some as old as in their mid-90s, they got in and immediately started practicing the basic strikes with the seniors taking the role of the sword and the juniors the role of the jo. The air filled with the cracking sounds from the strikes of jo against sword and the wild kiai that are the characteristic soundtrack of Muhi Muteki-ryu and we, as we always do in these “experience” articles, followed the practice from the inside under soke’s detailed explanations and with the help (and patience) of the 20 or so members of the school that were there that day.

Our talk with Nemoto soke was cut short by the arrival of the Meibukan members. Some already dressed for practice, and some in their street clothes, some from the area and some from as far as Tokyo, some as young as in their early 20s and some as old as in their mid-90s, they got in and immediately started practicing the basic strikes with the seniors taking the role of the sword and the juniors the role of the jo. The air filled with the cracking sounds from the strikes of jo against sword and the wild kiai that are the characteristic soundtrack of Muhi Muteki-ryu and we, as we always do in these “experience” articles, followed the practice from the inside under soke’s detailed explanations and with the help (and patience) of the 20 or so members of the school that were there that day.

The basics: Strike one and strike two

The first thing we did were of course two of the kihon strikes using the Honuchi and the Gyakuuchi grip: shidachi starts from Muhi Muteki-ryu’s low basic kamae, a left hanmi side posture that could be thought of as a cross between Itto-ryu’s In no Kamae and a standard kendo hasso where the left hand holds the jo on one end at right hip level and the right hand with the index finger pointing upwards at around the one-third mark at ear height. Uchidachi is holding his sword at a kamae that would correspond to what Itto-ryu calls a chu-seigan i.e. a seigan where the tsuba is at eye level and the reason for this is to make sure that even a strong strike won’t end up hitting uchidachi in the head. Shidachi moves forward without changing the height of his hips, moves the left hand along to his belt to his left hip, turns his body completely to a right hanmi and as the right foot comes forward, strikes with the jo the sword at around the middle and in one movement slides down to the tsuba completing the strike –this is where the leather guard proves to be invaluable. The sword drops and if done correctly, the tip of the jo is at uchidachi’s center line at around throat level and just a couple of centimeters/one inch before connecting.

Honuchi 1

Honuchi 2

Honuchi 3

Gyakuuchi 1

Gyakuuchi 2

Gyakuuchi 3

This basic striking technique is performed tens of times with the practitioner going from the Honuchi grip to the Gyakuuchi (the right hand reverses its position so now the thumb is downwards, just like Shinto Muso-ryu’s yakute) and then from just a slide step forward to a much bigger step with the right knee being raised at waist level –this is also a very characteristic Muhi Muteki-ryu movement, which besides allowing shidachi to cover more distance, makes him much more threatening to the opponent. Incidentally, all these strikes are practiced with strong kiai because kiai are central to Muhi Muteki-ryu and there are different, in sound, intensity or duration depending on the place they are used in the kata: among the schools I have seen, Muhi Muteki-ryu is probably the one with the most extensive use of kiai and they really change the way performing the techniques feel as well as how they look from the outside. When all practitioners have done their rounds and have worked on their basic technique, they move to the kata which are spread over three sets: Omote (four kata), Chui Goko (five kata) and Gokui Juko (ten kata) –if you think that this is a small curriculum, you would be wrong because these kata include several exchanges, starting from the very first one that introduces newcomers to the school: its name is Nanahon and as its name suggests it is indeed made up of “seven parts”. Which Nemoto soke was kind enough to lead us through.

This basic striking technique is performed tens of times with the practitioner going from the Honuchi grip to the Gyakuuchi (the right hand reverses its position so now the thumb is downwards, just like Shinto Muso-ryu’s yakute) and then from just a slide step forward to a much bigger step with the right knee being raised at waist level –this is also a very characteristic Muhi Muteki-ryu movement, which besides allowing shidachi to cover more distance, makes him much more threatening to the opponent. Incidentally, all these strikes are practiced with strong kiai because kiai are central to Muhi Muteki-ryu and there are different, in sound, intensity or duration depending on the place they are used in the kata: among the schools I have seen, Muhi Muteki-ryu is probably the one with the most extensive use of kiai and they really change the way performing the techniques feel as well as how they look from the outside. When all practitioners have done their rounds and have worked on their basic technique, they move to the kata which are spread over three sets: Omote (four kata), Chui Goko (five kata) and Gokui Juko (ten kata) –if you think that this is a small curriculum, you would be wrong because these kata include several exchanges, starting from the very first one that introduces newcomers to the school: its name is Nanahon and as its name suggests it is indeed made up of “seven parts”. Which Nemoto soke was kind enough to lead us through.

Nanahon: One is seven, seven is one

In most schools I know, the first kata a student learns is simple and is a container for the school’s most basic elements; Muhi Muteki-ryu’s Nanahon (which is usually performed together with the next one, the nine-part Kuhon) is not an exception but what makes it different is its complexity! The creators of the kata wanted to include in it pretty much everything, from Honuchi and Gyakuuchi to Yumihari, to Ko-guruma (the wrapping motion for using the sword’s mine/ridge to take it down and get to the opponent’s wrist), attacking and defending from a sitting position (because you have fallen down or to confuse the attacker) and more. Even just going through the motions step by step with Nemoto soke was challenging enough; actually performing them with the intensity and sense of distance they should be practiced is a daunting task so it is no surprise that it takes years to learn adequately enough to be able to move to the next set.

So how does it go? First the two opponents leave their weapons crossed in the middle of their distance, they retreat five steps, hitch their hakama up, bring their thumbs inside their fists, (a mudra i.e. hand-gesture evoking Marishiten, the Buddhist deity protecting warriors), do a kicking motion to clear the ground of any stones or other objects (a reminder that this is a tradition that started out in the fields), get close to their weapons, half-kneel, put on their hachimaki and then perform a move that is unique to Muhi Muteki-ryu and called Chuukiri, consists of mimicking picking up a blade of grass and breaking it in half and carries the meaning that what follows next is practice so even if there are injuries, both parties are to be blamed so they shouldn’t harbor hard feelings towards each other. The second the imaginary grass is broken they grasp their weapons, jump up with a kiai, take two steps back and start the kata.

Nanahon 1

Nanahon 2

Nanahon 3 (Chuukiri)

Shidachi starts in Yumihari and then brings the jo vertically in front of his body, holding it with only the right hand. He makes again a clearing-the-ground kick, as does uchidachi, and starts moving forward. Uchidachi is also moving forward, holding the sword lying on his right shoulder with the tsukagashira pointing at shidachi and when they reach engagement distance uchidachi starts a high cutting attack which shidachi immediately strikes down with a Honuchi and a thrust to the neck. Shidachi retreats two steps and goes to Yumihari and uchidachi crams him with two steps forward and a second high attack. Shidachi retreats two more steps, rotates the jo to bring it into a defensive position and rushes forward doing an overhead right Honuchi strike while raising his right leg for emphasis. Uchidachi raises the sword with his left hand on its mine (ridge) to block the strike and as he does, shidachi reverses hands and strikes from below with a Gyakuuchi.

Nanahon 4 (Yumihari)

Nanahon 5

Nanahon 6 (Honuchi)

Nanahon 7 (Rotating the jo into a defensive position)

Nanahon 8

Nanahon 9 (Overhead right Honuchi strike while raising the right leg)

Nanahon 10

Nanahon 11 (Strike from below with Gyakuuchi)

The two opponents separate, Shidachi goes to a Honuchi grip kamae and as Uchidachi takes a step forward to close the distance and strike, Shidachi does the basic Honuchi and takes the sword down. Shidachi retreats two steps and kneels on his left knee, extending his right foot to the front and a little to the left, with the toes pointing to the left; this movement is a trap for Uchidachi (Shidachi looks vulnerable so Uchidachi will want to attack) but also teaches the Muhi Muteki-ryu practitioner how to respond from a low position and as for the position of the foot, it is an allusion to stepping on the opponent’s foot to immobilize him. As Uchidachi moves in with a low cut, Shidachi rises while simultaneously rotating the sword to push it aside with a Ko-guruma and ends with a tsuki to Uchidachi’s solar plexus; after that, they both take two steps back and disengage with a “Sha!” kiai that always marks the beginning and end of a sequence.

Nanahon 12 (Honuchi)

Nanahon 13

Nanahon 14

Nanahon 15 (Ko-guruma)

Nanahon 16 (Tsuki)

If you have seen a Muhi Muteki-ryu enbu you have seen Nanahon: it is usually the first kata performed and sets the tone for what will follow, in the same way it does in its role as the entry point to the curriculum. It is so packed with action and intensity, with strikes and blocks and successive growling kiai that it’s almost hard to believe it is over in about 30 seconds and that both practitioners are still alive and uninjured at the end. And this isn’t for demonstration purposes: this is exactly how it is practiced at the Meibukan –as a matter of fact this is how the whole practice goes, from start to finish, from kihon to gokui. Muhi Muteki-ryu looks real because it is real.

Crushing the way to the 21st century

Doing several repetitions of the Nanahon took the best part of the rest of the practice; when it was over and in preparation of the June demonstration at Kashima Jingu, Nemoto soke set up an extended demonstration of Iga-ryu-ha Katsushin-ryu Jujutsu the jujutsu school that he has inherited and is also taught at the Meibukan; needless to say it is interesting enough to deserve its own article and perhaps we will do that, some time in the future. In the end, and when everyone else had gone, soke was kind enough to grant us an interview and have a conversation about the school’s past, present and future. Which, judging from what we saw and experienced and from what he told us, seems to be quite bright: back in the days of his father and predecessor, Muhi Muteki-ryu was more popular among the local youth (fifty years ago diversions were fewer and so where budo and sports options) and one look at its 1982 video in the Nihon Kobudo series, where about 40 people, half of them children, are practicing under Nemoto Heizaburo at Hiraiso beach, confirms it but the dojo does have several dozen members of all ages who practice regularly and actively so it looks like it will make it through its fifth century as well!

Iga-ryu-ha Katsushin-ryu Jujutsu(Idori)

Iga-ryu-ha Katsushin-ryu Jujutsu(Tachiai)

It isn’t just about survival though: it rarely is with these traditions. It is about being really alive, being vibrant and being relevant to the realities of each coming era. Muhi Muteki-ryu is and despite the fact that it operates from a small, out-of-the way town, it is pulsating with vigor and anyone who has the opportunity to see it will attest to that. Although it was developed by common people for common people and is using one of the most common tools found in any culture, it has that level of depth and intricacy that makes koryu budo a fascinating subject to follow and study and its headmaster and practitioners have the self-confidence that comes from knowing they are practicing something that is real and solid and sincere. And I can’t help thinking that if all koryu budo was like that, the landscape of Japanese martial arts would be very different.

PS

This article wouldn’t had been possible without the collaboration of soke Nemoto Kenichi and his students: I would like to thank them publicly for their patience and understanding and to apologize for intruding and upsetting their practice, despite the fact they were preparing for an important demonstration; particularly my three partners, Oowaku Masayuki, Morishima Kenichi and the legendary Yasu Niro who has been a member for 45 years and remains, at age 93, strong and fearsome. The warm and friendly atmosphere in their dojo is, I am sure, one of the main reasons their school is thriving and being able to experience it even for a few hours has been an honor and a privilege.

Grigoris Miliaresis

About the writer

Grigoris Miliaresis has been practicing Japanese martial arts since 1986. He has dan grades in judo, aikido and iaido and has translated in Greek over 30 martial arts’ books including Jigoro Kano’s “Kodokan Judo”, Yagyu Munenori’s “The Life-Giving Sword”, Miyamoto Musashi’s “Book of Five Rings”, Takuan Shoho’s “The Unfettered Mind” and Donn Draeger’s “Martial Arts and Ways of Japan” trilogy. Since 2007 his practice has been exclusively in classic schools: Tenshin Buko-ryu Heiho under Ellis Amdur in Greece and Kent Sorensen in Japan and, since 2016, Ono-ha Itto-ryu under 17th headmaster Sasamori Takemi and 18th headmaster Yabuki Yuji.