Jitte: The Samurai Police Weapon of Authority and Control

Text by Robert R. Gray

1: What is a Jitte?

A jitte is an Edo-period (1603–1868) arresting weapon carried by samurai police such as yoriki and doshin, as well as other officials. It was designed not to kill, but to disarm an opponent’s sword and subdue them. The jitte also functioned as a symbol of authority, much like a police badge does today. Colored tassels attached to the handle indicated one’s rank and position.

Utagawa Kuniaki, Zōho Sōkyū Tomoe, kabuki actor print, 1861. National Theatre Collection.

The standard reading of 十手 is jitte, though some dictionaries, including Shinkokugo-jiten and Kojien, list “jutte” as a rare secondary reading. A few martial arts schools also use this pronunciation. In Nawa Yumio’s Jitte Torinawa Jiten, the last major scholarly study of the weapon, he records more than fifteen regional and school-specific names. Ikkaku-ryu, for example, refers to it as tebo (hand staff). Another term, ginbo (silver staff), reflected the polished or silver-coated finish of some high-ranking officials’ jitte. The term ginbo, however, was no compliment. It was a derogatory term for the jitte said behind officials backs.

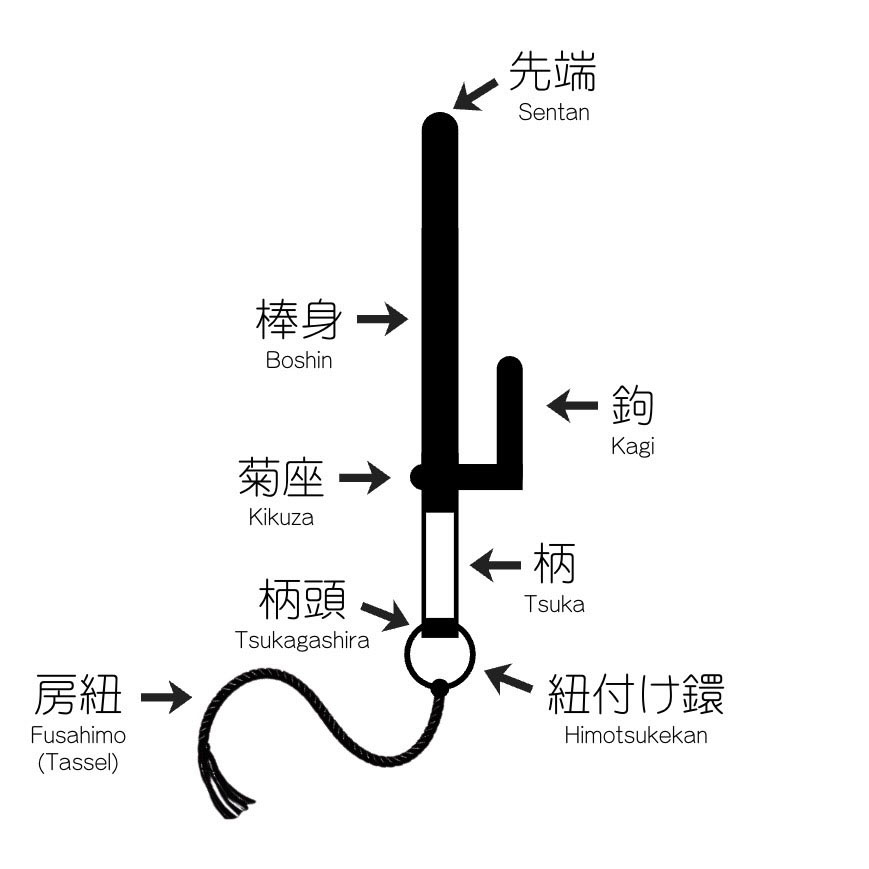

2: Structure of the Jitte

The jitte is made up of several distinct parts, each with a specific function. The main shaft is the boshin, providing reach and strength. It was used to strike the opponent and deflect his weapon. The boshin was hand-forged, typically from round or hexagonal iron bars. Round bars were more common due to ease of manufacture, while hexagonal bars were stronger but more labor intensive to make and therefore more expensive. Standard police jitte were round, but officers could pay out of pocket and commission higher quality pieces if they wished.

Illustration by Rengo Gray

The most common length for the boshin was between 40-50 cm (about 16–20 inches). But to determine the ideal length for a privately commissioned piece, the following practical rule was used: “When holding the jitte in a reverse grip with the boshin snug against your arm, the tip should extend slightly beyond your elbow. This way, your arm is fully protected while the jitte remains short enough to be convenient to carry and use with one hand.” The tip, or sentan, was blunt and flat, allowing for strikes and thrusts without piercing the body. The goal was to arrest, not kill.

Jinen-ryu jutte-jutsu1-1

Jinen-ryu jutte-jutsu1-2

Jinen-ryu jutte-jutsu1-3

Extending from the side of the boshin is the kagi, the forged iron hook used to catch and control an opponent’s sword. It also prevented the hand from sliding forward similar to a tsuba on a sword. To attach the kagi, a square or rectangular hole was hot-punched through the boshin and the kagi tang was driven through it while still hot. As the iron cooled, it shrank, locking the tang in place. The protruding end on the opposite side was then mushroomed or hammered flat, creating a rivet-like head. The decorative plate covering this rivet is the kikuza.

Early prototype jitte

In the early Edo period, considerable experimentation took place to determine the ideal size and shape of the kagi. This resulted in some highly unusual jitte, including examples with oddly shaped hooks and even multiple kagi on a single weapon.

Multiple kagi

Below the kagi is the handle (tsuka or nigirie). The tsuka is sometimes wrapped in samegawa (ray skin) for a better grip. This term has an interesting history. The kanji, 鮫皮 (samegawa) literally means “shark skin,” but when it comes to Edo-period weapon handles (including sword), it actually refers to ray skin, not shark. Historically, the character used for shark had a broader meaning and included both sharks and rays. The Edo craftsmen preferred ray skin, 鱏皮(eikawa), such as stingrays, because the surface is covered with hard, knobby bumps that provide a better grip and take lacquer well. Shark skin is smoother and less practical for weapons, but the shark kanji stayed in use out of tradition.

samegawa jitte

Other handle materials included braided cord, metal plating, deer hide, and cowhide. Brass-plated handles were especially common in the Choshu domain (modern-day Yamaguchi Prefecture). Tanned deer and cowhide were typically associated with higher-ranking officers, while jitte carried by low-ranking officers often lacked any grip covering at all. At the base of the handle is the tsuka-gashira, which could also be used for striking.

Jinen-ryu jutte-jutsu2-1

Jinen-ryu jutte-jutsu2-2

Jinen-ryu jutte-jutsu2-3

Attached to the bottom of the handle is the himotsukekan, the fitting that allows a tassel to be tied to the weapon. The tassel as a whole is known as a fusa-himo with fusa referring to the ball-shaped end and himo to the cord. Tassel color indicated rank: in Edo, purple was reserved for magistrates and police supervisors, while red was used by lower-ranked patrol officers. Other regions followed different color systems—green tassels in Yamagata and Miagi, for example, and black in Osaka.

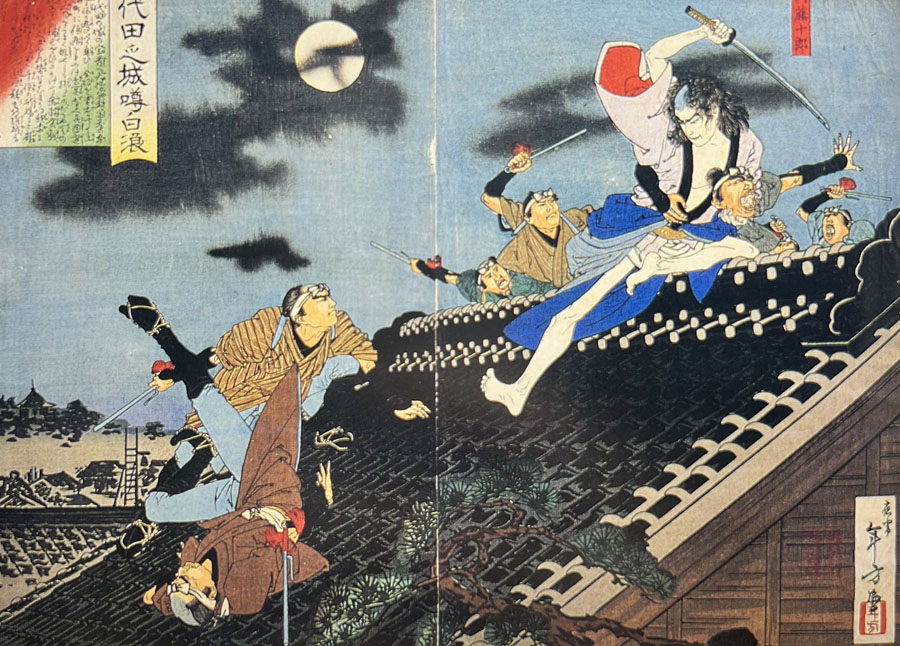

Mizuno Toshikata, The Capture of Fujioka Tōjūrō, color woodblock print, 1885.

In Mitamura Engyo’s Torimono no Sekai (The World of Arrests), he writes: “Patrol officers carry polished jitte with red tassels. They are the ones considered the most intimidating.” Red-tasseled officers were considered especially intimidating because they carried out arrests directly, as opposed to their purple-tasseled superiors who merely gave the orders.

In Kitagawa Morisada’s late Edo–period work Morisada Mankou, he describes the use of jitte in Osaka: “Foot soldiers and patrol officers wore a sword on the left hip and a jitte on the right. The tassel of the jitte was black and three shaku in length. Those carried by chori (people with the lowest rank), however, had red tassels.” Interestingly, in Edo itself, anyone below the rank of patrol officer was not permitted to attach a tassel at all, as they were considered to have no rank.

In late Edo, some schools are said to have begun wrapping the tassel around the wrist to better secure the grip and prevent dropping the weapon during a confrontation. However, most earlier tassels were too short for this purpose, and this method of holding the jitte is notably absent from any known densho.

3: Origins and History

The jitte itself didn’t exist before the Edo period, but a number of precursors did. Let’s trace that evolution.

Hananeji (鼻捻)

hananej

The oldest precursor is the hananeji (“nose twist”), first documented in the Heihanki (兵範記) of 1167. Originally used to restrain horses, it consisted of a short rod with a loop of rope attached. When placed over the horse’s nose and upper lip, twisting the rod tightened the loop, producing increasing pain until control was achieved. During arrests, the loop was applied to a suspect’s wrists, allowing the individual to be restrained and escorted safely, while the rod itself could also be used for striking if necessary.

Habiki (刃引)

A habiki (literally “pulled blade”) began as a standard sword with the cutting edge blunted. It was used for striking and subduing opponents when killing was undesirable—exactly the purpose associated with the jitte. Because a habiki did not need a sharp edge, the metal did not require hardening, allowing these weapons to be produced faster and at lower cost than swords. Their use expanded in the late Sengoku period (1570s–early 1600s) as combat shifted from open battlefields to castle towns, where restraint became more important than lethal force.

Tetto (鉄刀)

Tetto

In the late Muromachi period (1467-1573), the habiki evolved into what came to be known as the tetto (literally, “iron sword”). The tetto retained the blade-like shape of a sword but was made of iron rather than steel, making them faster and cheaper to produce. Steel is ideal for cutting, but when used for striking it can bend or crack. Iron, by contrast, holds up better to repeated impact. Over time, the tetto grew increasingly utilitarian, becoming shorter, with simpler handle mountings and reduced curvature.

Kabutowari (兜割)

The kabutowari was a related weapon that developed as an offshoot of the tetto. While it retained the tetto’s basic form, it typically lacked a scabbard and had its handle fittings stripped away, resulting in a simpler, bare iron weapon. Most examples still showed a slight curve, reflecting their sword ancestry. With the loss of handle fittings, a small hook was added near the top of the handle to act as a belt stop. Through practical combat and police use, it was soon recognized that this hook could also catch an opponent’s armor or control their weapon. However, when drawn like a sword, the hook sat on top, whereas receiving an opponent’s weapon was far more effective with the hook on the bottom. Once this was understood, the kabutowari was straightened—making it easier to draw with the hook facing downward—and the hook itself was reinforced and enlarged. These changes became the defining features of the weapon that ultimately replaced it: the jitte.

kabutowari(Photos by Paul Richardson)

Early Edo (1603-1650) and the Appearance of the Jitte

From the early Edo period, castle guards were prohibited from drawing their swords inside Edo Castle, despite being expected to restrain or arrest unruly individuals. This restriction was a key factor in the rise of the jitte as a practical police weapon. Under the Tokugawa shogunate, urban policing became increasingly formalized into a tiered system: yoriki (senior supervisors), doshin (lower-ranking officers), and okappiki (civilian assistants hired by doshin). The system also standardized the use of torimono (arresting tools designed to control rather than kill). While yoriki and doshin were samurai, okappiki were not.

Early Edo period jitte

Early Edo period jitte

Records from machi-bugyo (town magistrate) offices list the standard weapons issued to yoriki as:

-

- Katana and wakizashi (long and short swords)

- Jitte

- Tessen (iron fan)

Standard issue for doshin:

-

- Katana (long sword only)

- Jitte

- Kusarifindo (weighted chain)

- Sasumata (forked pole for pinning suspects)

- Tsukubo (push pole for crowd control)

- Sode-garami (barbed pole for entangling sleeves)

- Hojo (arresting rope)

- Yobiko (whistle)

Standard issue for okappiki:

-

- No swords (as they were not samurai)

- Jitte (without tassel, as they had no rank)

- Kusarifundo

- Hojo

Mid-late Edo (1650-1800)

This period marked the height of jitte culture. The weapon’s form and structure became more standardized, techniques matured, and jitte-jutsu emerged within kobudo grappling schools. Takenouchi Hangwan-ryu is the earliest verifiable tradition to include jitte use. Founded in 1532, the school formalized its jitte techniques during the Edo period.

Yagyu Shingan-ryu developed jitte methods alongside grappling and other short weapons, with a strong emphasis on controlling armed opponents. Closely connected to samurai law-enforcement, the school partially integrated policing practices into its system. Reflecting its ties to Shingon Buddhism, Yagyu Shingan-ryu adopted a distinctive jitte handle engraved with a five-pronged vajra (五鈷杵, gokosho), a ritual implement used in Shingon mikkyo. Within their symbolic system, the jitte represented the sword held in the right hand of Fudo Myo, while the hojo arresting rope echoed the demon-binding rope held in his left.

Masaki-ryu is an Edo-period martial tradition best known for its jitte and manrikigusari techniques. Its 10th soke was Nawa Yumio (1912–2006), who was not only head of the lineage but also the most influential modern researcher of jitte and Edo-period police weapons. Another well-known jitte lineage was Kasunoki-ryu, which developed an unusually thick kagi that later became common among Kanto-area police. Dozens of other jitte-using schools also existed.

Edo period, wooden training jitte(Photos by Paul Richardson)

Late Edo Period (1800-1868) and Beyond

While early-Edo jitte were generally sparse and utilitarian, late-Edo examples marked the peak of ornamentation—much like the progression of ancient Greek columns from the plain Doric to the highly elaborate Corinthian. At the same time, Western weapons were entering Japan and policing practices were rapidly evolving. Although the jitte retained symbolic authority, its practical use declined quickly. By the 1870s it was abolished as an official police weapon, surviving mainly in private collections and martial arts schools. Today, jitte are gaining popularity as collector’s items, as they are far more affordable than swords and require no license or special paperwork to own.

Jinen-ryu jutte-jutsu 3-1

Jinen-ryu jutte-jutsu 3-2

Jinen-ryu jutte-jutsu 3-3

Jinen-ryu jutte-jutsu 3-4

Jinen-ryu jutte-jutsu 3-5