Ittō-ryū: Beyond the Jagged Edge: The Sword That Penetrates at a Single Point

Hiden Magazine, April 2007

By Nomura Akihiko

Translated by Mark Hague

An Obsession with One

Ono-ha Ittō-ryū is One is Victory, Two is Defeat.”

Thus said Sasamori Takemi, the 17th Sōke of Ono-ha Ittō-ryū. A single cut of a sword will decide the outcome of a fight while two cuts will lead to defeat. This is a straightforward tactic that eliminates all that’s unnecessary, allowing you to attack directly into your opponent’s center line by taking the shortest distance possible. This is the basic combat principle of Ittō-ryū.

They say that in Ono-ha Ittō-ryū, which contains the concept that One Sword is Many Swords; Many Swords are One Sword, “One is at the beginning, and One is at the end.” The One referred to here, the fundamental principle of Ittō-ryū, is none other than [the technique of] kiriotoshi, which can be described as the very hallmark of the school.

In Ono-ha Ittō-ryū, students practice kiriotoshi by doing the fifty moves contained in the Odachi kata, which is the first kata they learn. It is no exaggeration to say that the fundamentals of Ittō-ryū are distilled within the techniques of this two-person form. Hitotsugachi, which is the very first of the fifty moves students are taught within the Odachi kata, has become the vehicle through which students learn the most fundamental sequence of kiriotoshi. Which means that they are learning the school’s inner-most secrets from day one.

The kata itself is really very simple.

Both parties approach each other using ayumiashi. As soon as they enter striking range, both Uchikata and Shikata cut at what looks to be the same time. The timing of these cuts appears to the casual observer as nothing more than both sides cutting each other simultaneously, but Shikata’s sword firmly cuts into the line of Uchikata’s strike, forcing his blade to the side while controlling the center line. This is kiriotoshi.

After his initial cut is struck down, Uchikata backs up and recovers to a left jōdan. Shikata cuts down on his left kote, steps backs to the appropriate distance, and maintains zanshin. This completes the sequence.

This kata starts with Shikata cutting away his opponent’s slashing attack with his first cut and then cutting into his opponent’s kote with his second sword stroke; however, you will never understand Ittō-ryū by just taking what you see at face value. The timing of this is not first cutting away the sword and then cutting the opponent in two separate beats. It is a sword that cuts down the enemy in a single beat with a single stroke.

To understand this, you have to know what goes on inside the technique of kiriotoshi the instant it is executed.

The seigan kamae is at the core of Ittō-ryū. When assumed in Ono-ha Ittō-ryū, the sword tip extends to between the opponent’s eyes or base of their throat, a much sharper angle than in kendo. The intensity contained in this sword tip is what gives rise to the secret, kiriotoshi.

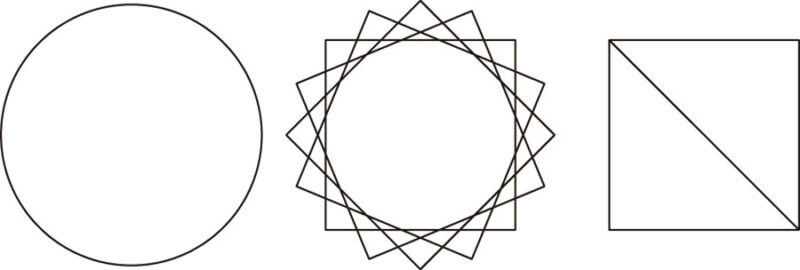

What Shape Has the Most Corners?

In Ittō-ryū, it has been taught that the shape with the highest number of sharp corners is the circle. If you were to overlay shapes that have corners on top of each other, you would start with a triangle, then get a square, then a pentagon, and ultimately end up with a circle. This circle is not one in which the jagged edges of the shapes have been smoothed down to nothing, but one in which the corners of these shapes are arranged in such a way that there are no gaps between them. No matter where on its circumference you touch it, your point of contact will be a razor-sharp point where the most power is concentrated the instant you make contact. This is Ittō-ryū’s Sharp Circle.

In Ittō-ryū, a circle isn’t seen as a shape with no corners, but rather as a shape with the most corners. One fundamental principle of kiriotoshi is to capture the opponent’s sword at a single spiked point on the circumference of a circle, keeping the power concentrated there, and then drawing it into a continuous series of points as it is cut down using kiriotoshi.

Because kiriotoshi is completed in just a fraction of a second, it appears to an outside observer that Shikata just cuts straight into his opponent. In actuality, Shikata moves his sword in a smooth circle while cutting along the side of Uchikata’s blade, sliding his sword down from Uchikata’s monouchi to his tsuba.

When Shikata’s blade moves in this manner, those in Ittō-ryū refer to it as crossing over. Shikata’s blade sliding along Uchikata’s with the sharp tip of his sword projecting forward is like crossing over a bridge. If both sides were to try to cut down directly toward each other, their sword blades would collide, and if your opponent were stronger than you, you would be overpowered by him and get cut instead. It is because you move your sword in a circle that your opponent’s strength and the size of his weapon don’t matter; you will be able to “cross over” while forcing his blade to the side.

The destination that your sword tip crosses over to is your opponent’s center line. Within the formal kata, Shikata’s sword tip ends up firmly pointed at Uchikata’s throat, but if Shikata were to take one extra step forward when he cut, he would be able to split Uchikata’s head in two. The fight would essentially be over at that point.

But in the kata, Uchikata cannot afford to stop with a sword tip bearing down on him, so he takes a step back and raises his sword to a left jōdan. At that point, Shikata strikes his left kote. However, this isn’t a strike to the forearm, but a strike aimed at the head that is absorbed by thick and sturdy gauntlets called onigote that are unique to Ittō-ryū and which are used to ensure safety during training.

Kiriotoshi 1

Kiriotoshi 2

Kiriotoshi: The Prefatory Secret

In the very first move of the Odachi kata, called Hitotsugachi, the most foundational expression of kiriotoshi can be seen. In this kata, Uchikata cuts straight down with his sword. Shikata also cuts straight down, but as he does, he uses the side of his blade to deflect Uchikata’s sword to the side while bringing his own sword tip to rest at Uchikata’s throat. This secret way of cutting is truly taught from the very beginning.

Kiriotoshi 3

Shikata finishes by striking down on Uchikata’s upraised kote. The distinctive way they practice this cut, which developed in this school, predates the invention of protective gear used in kendo. In a real situation, there’s no need to wait for the arm to be fully raised.

The principles of kiriotoshi that are contained within the kata of Hitotsugachi must hold true with swords of different lengths, such as medium-length swords and short swords, not just long swords.

In the case of a short sword, for example, because the length of the blade is so short, they developed ingenious tactics, like taking up a hanmi posture and rapidly closing in on their opponent using unique footwork called, chidoriashi, to rob their opponent of the advantage of distance. But once they enter striking range and their blades come into contact, they still use the same skill of “crossing over” as previously discussed regarding the long sword. At this stage, the length of the blade doesn’t matter. Because the opponent is robbed of his center line and his sword is completely deflected to the side, the more power he applies to his strike, the more power is drained from it when he cuts.

Kiriotoshi with a Short Sword 1

Kiriotoshi with a Short Sword 2

Kiriotoshi with a Short Sword 3

Kiriotoshi with a Short Sword 4

Kiriotoshi with a Short Sword

Shikata attacks an opening in Uchikata’s defenses while holding a short sword by boldly closing the distance using a stepping method called chidori. By the time Uchikata goes forward, hastily trying to intercept him, Shikata has already closed the distance, and Uchikata overshoots his optimal striking range, finding himself in a tsuba-to-tsuba bind. Here, too, Shikata controls Uchikata’s tsuka using the movement of the Sharp Circle.

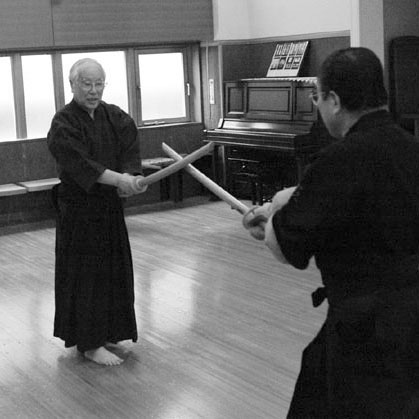

Taijutsu application 1

Taijutsu application 2

We were fortunate to have the sōke unveil an example of applying the secret of kiriotoshi in a taijutsu context. Sasamori Sōke stands casually facing a swordsman who is quite close and about to cut. The instant his opponent moves, Sōke sticks out his right fist, punching the swordman’s left hand. Although not a strong blow, because he connects with a point that is directly connected to his opponent’s center line, the swordsman staggers back and isn’t able to cut.

Settle the Match the Instant You Face Off

As a modality, kiriotoshi takes the form of Shikata cutting away his opponent’s attack, but the original intent of this practice was to cut directly into the opponent’s center line in a single beat. But even in paired practice, Uchikata doesn’t just stand there like a dummy, allowing himself to be cut. If one were to just recklessly charge in head-on, it would end up as a collision of forces—a simple contest of strength. If done this way, it would be utterly impossible for a short sword to overcome a long sword.

Hitotsugachi starts when both opponents advance toward the other using ayumiashi, with Uchikata in in-no-kamae and Shikata in a seigan posture, but by the time they enter striking range, Shikata has to have already taken control of Uchikata’s center line. In other words, starting from when both parties take up a stance out of range of the other, Uchikata is driven to the brink of thinking, once he gets into range, an attack is certainly coming.

As Shikata closes the distance, putting on the pressure, Uchikata feels he has no choice but to cut Shikata just as he is about to enter striking range. At that point, however, Shikata makes a very small opening to his left to invite Uchikata to attack from that direction. This invitation is such a small adjustment that an outside observer would never notice it, but Uchikata reads it, shifts his position slightly, and cuts down from Shikata’s left. Both sides do what appears to be straight, downward cuts, but in fact, Uchikata steps to the side ever-so-slightly. You could also say that this move by Shikata gets Uchikata to act, causing the cut to come in slightly off-line.

Picture 1

Picture 2

Picture 3

Here, Uchikata assumes a posture with his sword held vertically along his right side, called in-no-kamae. Shikata, who is in a seigan stance, presses forward with the tip of his sword aimed at the bridge of Uchikata’s nose, determined to stab (1). As the flustered Uchikata raises his sword to break the impasse, Shikata also simultaneously raises his sword to jōdan kamae (2). They say that, at this moment, Shikata subtly creates a slight opening along the left side of his body, inducing Uchikata to act without him realizing it. It’s a movement too subtle to be seen by the naked eye, but it works because it gets Uchikata to act on instinct (3).

If the sword in Ittō-ryū that capitalizes on the opponent’s movement to achieve victory is called the Life-Giving Sword, then the sword of Ittō-ryū that decides whether one’s opponent lives or dies the moment they face off is indeed the Death-Dealing Sword. The moniker, Death-Dealing Sword, has a malicious ring to it, but is an expression that best describes the fundamental essence of the applied principles of Ittō-ryū.

What’s important here is kamae.

In Ono-ha Ittō-ryū, there are various kamae, such as: in, yō, wakigamae, onken, kasumi, hongaku, and of course seigan, but no matter which stance you assume, the moment swords are drawn at a distance, you are still required to take your opponent’s center by cutting into his sword as if driving in a wedge.

A firmly rooted position 1

A firmly rooted position 2

A firmly rooted position 3

A firmly rooted position 4

A Firmly Rooted Position

Try knocking to the side a sword held in a seigan kamae by striking the area around its monouchi. If the sword tip wobbles a lot, it fails the test (1-2). If you are in a stance in which you can absorb a strike from an opponent from the base of your own sword as flexible as “a willow withstands the weight of snow,” the sword tip will barely move. (3-4).

Always keep your mental focus and physical posture going forward 1

Always keep your mental focus and physical posture going forward 2

Always keep your mental focus and physical posture going forward 3

Always keep your mental focus and physical posture going forward 4

Always keep your mental focus and physical posture going forward.

The photos show a student transitioning from seigan to in-no-kamae. Photos (1-2) show him taking a step backward. While it depends on the skill of the individuals involved, backing up tends to take the pressure off an opponent within striking range, ceding the advantage to him. It also shifts one’s weight backward, making it harder to react. Photos (3-4) show the student taking up in-no-kamae while stepping forward. Although the sword tip moves off the centerline, this movement maintains his ability to control his opponent at the tsuba while keeping the pressure on. Even when a kata involves moving backward, failing to keep your mental focus and physical posture going forward will keep you from demonstrating the quintessence of Ittō-ryū.

Gedan Kasumi 1

Gedan Kasumi 2

Gedan Kasumi 3

Gedan Kasumi 4

The Pressure of Stance as Seen in the Fourth Move of the Odachi kata: Gedan Kasumi

This technique appears to give form to the invisible pressure within a space. Shikata enters striking range by touching his sword to Uchikata’s, pressing it down (1). When Uchikata can no longer bear the pressure, he pulls his sword away and attempts to strike. At that very instant, Shikata, having moved slightly to the left with his left foot, performs kiriotoshi against Uchikata’s sword. In this technique, Shikata doesn’t precisely meet Uchikata head-on. He subtly shifts his position, but this shift is only perceived by Uchikata. Shikata maintains a constant forward pressure on Uchikata throughout. Here too, a complex and “sharp” circular movement is utilized.

Shikata mustn’t lose his posture the moment Uchikata pulls his sword away. Instead, he must cross his sword over with an elastic “fixing power” while maintaining his kamae.

Also, most kenjutsu schools seem to fundamentally believe that you need to control your opponent’s center line through the use of the sword tip, but in Ono-ha Ittō-ryū, they have the lesson of Starting Seven Inches from the Tsuba which calls for controlling your opponent’s blade not from your sword tip but from a point seven inches from your own tsuba. Depending on the technique, there are times when, for instance, your sword tip might appear to move off-target when the blade is held flat. Though at first glance it may appear to have moved off the center line, in fact, you firmly control your opponent’s blade from near the base of your own tsuba. Moreover, because you concentrate your power near your tsuba and not in the monouchi or tip of your sword, your body and sword become unified. As a result, your power crosses over from your tsuba to your sword tip as you maintain a stable foundation that is not easily unbalanced, and this allows you to generate strong striking power.

The value of Seven Inches from the Tsuba 1

The value of Seven Inches from the Tsuba 2

The value of Seven Inches from the Tsuba 3

The value of Seven Inches from the Tsuba 4

The Value of Seven Inches from the Tsuba

Ono-ha Ittō-ryū’s lesson of Seven Inches From the Tsuba is one of the secrets that runs through everything, from their kamae to the very act of cutting. As long as you always view the shortest distance connecting you and your opponent as being within seven inches of your tsuba, your sword will take the center and reach your opponent at its maximum extension, even though the sword tip may not be pointing at them. In fact, even kiriotoshi isn’t executed with the monouchi. By cutting down using the area seven inches from your tsuba, you gain stable attack angles, direction, and striking power.

The application of Seven Inches from the Tsuba 1

The application of Seven Inches from the Tsuba 2

The application of Seven Inches from the Tsuba 3

The application of Seven Inches from the Tsuba 4

When you master the lesson of Seven Inches From the Tsuba, you can start to exert great power through small movements that come from your center. In old schools of kenjutsu, you often see many techniques where practitioners turn their bodies sideways to deflect an attack when facing an opponent’s thrust (1-2). In Ono-ha Ittō-ryū, however, a slight rotation of the wrist enables a technique where you cross over your opponent’s sword as if rubbing against it with your shinogi as you thrust in with your sword tip (3-4). Even though you are stabbing, the shared awareness of “drawing in” your opponent makes them unconsciously accept the sword tip as if they were being sucked in by it.

Keeping Hold of a Single Point

There are also techniques in Ono-ha Ittō-ryū handed down from the past, such as Futatsugachi and Hoshatō, that assume you will be fighting multiple attackers, not just man-to-man.

Futatsugachi is a technique in which you appear to repeat Hitotsugachi twice.

First, Hitotsugachi is done. Then, right after Shikata transitions to zanshin, Uchikata starts to attack for a second time and Shikata does Hitotsugachi again. This scenario assumes two opponents attacking in succession, and while the kata requires doing it twice, you can do it three or four times to get the knack of dealing with multiple opponents.

This is where the critical meaning of zanshin is put to the test. It is said that zanshin does not mean the end, and when doing the move of Futatsugachi, Uchikata truly comes in to cut again, so zanshin cannot be simply a feeling but must be an action conducted according concrete principles.

In the kata of Hoshatō, which was compiled by Itō Ittōsai based on his experience of being attacked by multiple opponents, Shikata does one technique after the other while constantly changing his stances and angle of attack. This, too, isn’t about performing each move as a separate sequence, so Shikata has to constantly keep an eye on Uchikata. In a real situation, it would be normal for different opponents to step forward one after another, with each new one appearing as soon as the previous is dispatched.

Hoshatō 1

Hoshatō 2

Hoshatō 3

Hoshatō 4

Hoshatō 5

Hoshatō: “Four Cuts”

Many of the consecutive attacks performed in Ono-ha Ittō-ryū, which maintains One is Victory, Two is Defeat as a guiding principle, assume an engagement against multiple opponents. The Four Cuts of Hoshatō, in which Shikata strikes Uchikata’s raised kote, slips past his side, changes direction, and then strikes again, is also said to be based on techniques the school’s founder used to escape a perilous situation when he was surrounded in the dark (1-5).

Hoshatō 6

Hoshatō 7

Hoshatō 8

Shikata maintains awareness of his opponent’s center line even amidst the chaotic movements of offense and defense, never allowing his sword to stray from it (6–8). Although the form may differ, it is unmistakably one of the secrets of kiriotoshi.

Within the school of Ono-ha Ittō-ryū that was founded upon the fundamental concept of deciding victory or defeat with one cut of the sword without blocking or retreating, there are also techniques where one steps back. One of them is Tsubawari, the third move of the Odachi kata. Shikata is able to defeat his opponent by stepping back out of the range of his cut and then immediately counter-attacking by moving back in. But in Ittō-ryū, the footwork used to move back is not taught as backing up, but as hauling in. This isn’t a mere rhetorical device.

Shikata takes up seigan and closes in on Uchikata while controlling the center line. Uchikata cannot bear it when Shikata enters striking range, so he makes a cut. At that point, Shikata takes a half-step back, out of range, to avoid Uchikata’s strike. Shikata doesn’t dodge the cut that comes in; he gets the cut to come in and then backs out of range to evade it. This is a significant difference. In order to cut, proper timing is essential, but when Uchikata’s cut misses the mark and goes past Shikata’s tsuba, his timing is thrown off. They call that no-timing.

Waiting until the last moment to let your opponent cut is the same as described in the introductory discussion about kiriotoshi, but whereas kiriotoshi dominates within a razor-thin angle, this no-timing dominates within a razor-thin margin of distance.

The Real Secret of Ittō-ryū

Currently, in addition to the sixty moves of the Odachi kata that Sasamori Sōke teaches at the Reigakudō dojo, when you add the moves of the Kodachi, Habiki, Battō and other kata, the curriculum of Ittō-ryū becomes quite extensive.

They say that what the first generation sōke, Ono Tadaaki, learned from Itō Ittōsai were long, medium, and short sword katas that had been passed down to Ittōsai from Kanemaki Jisai, as well as the Hoshatō kata that Ittōsai compiled based on his own actual fighting experience. Through the process of transmission through succeeding generations of masters, like the 2nd Sōke, Tadatsune, and the 3rd Sōke Tadakazu, the kata were further refined and organized into the wide-ranging curriculum that exists today. However, just because there are a large number of techniques doesn’t mean that they were haphazardly compiled merely for the sake of increasing their variety. Students experience many techniques in order to comprehend the inner mysteries of just one.

Hitotsugachi is the first move but, at the same time, also a deep secret, a gokui. Although it is the same technique, the depth of understanding of Hitotsugachi when first learned and the depth of understanding of Hitotsugachi achieved after practicing the extensive curriculum of Ittō-ryū is vastly different.

Ono-ha Ittō-ryū, which maintains that, “One is at the beginning, and One is at the end,” asserts that everything culminates in how one can smoothly execute Hitotsugachi. Kiriotoshi is a secret move that certainly could also be considered the nucleus of Ittō-ryū—but the true secret is not the technique in and of itself but the applied principles that underpin it and turn One Sword is Many Swords; Many Swords are One Sword into reality.

About the Reverend Sasamori Takemi: The Reverend Sasamori Takemi (1933–2017) served as the 17th Sōke of the mainline of Ono-ha Ittō-ryū from 1975 until 2017. Throughout his time as the headmaster of the Reigakudō—the hombu dojo of the school located in Tokyo, Japan—he taught over five hundred students worldwide and lectured and instructed annually in Japan, Asia, Europe, and the United States. He was regularly featured in Gekken Hiden magazine, where he was known for providing simple and clear explanations of the inner secrets of Ittō-ryū. He also served as the founding pastor of the Komaba Eden Church in Tokyo, where he ministered to over 150 parishioners.