Alan Ruddock, an Irishman in the Footsteps of O Sensei

In this series, I try to bring to the attention of the Japanese public a number of foreign practitioners without whom Aikido would not be as widely practiced as it is today. Few people deserve the title of pioneer as much as the individual I would like to present today, for he not only introduced the practice of Aikido in his country, Ireland, but also that of Karatedo.

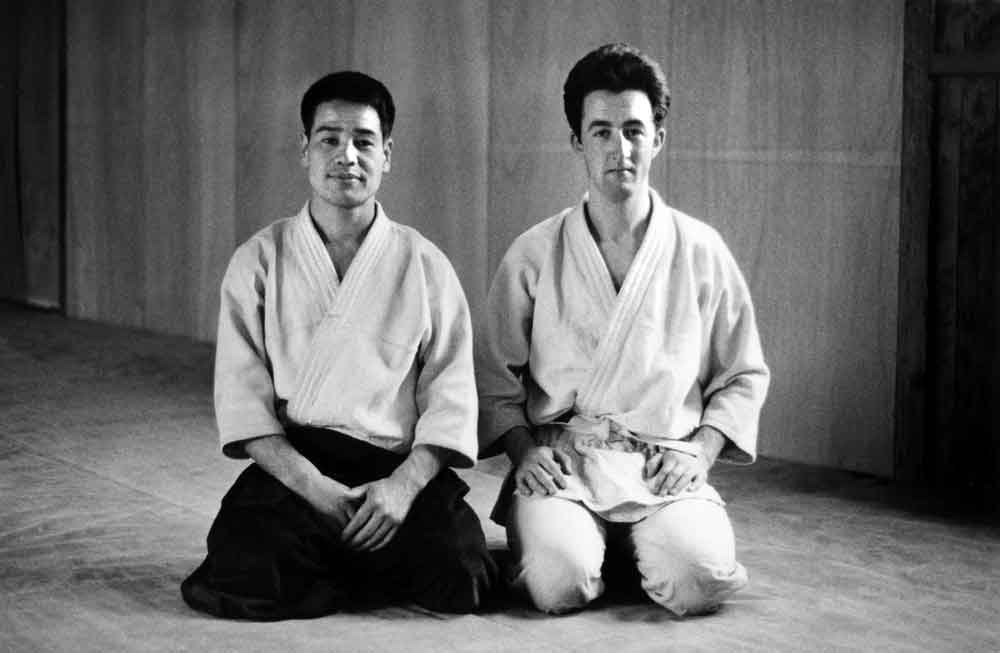

Murakami Tetsuji and Alan Ruddock

Alan Ruddock was born in Dublin in 1944. At age thirteen, his life-long interest for budo was triggered when he stumbled upon a book on Judo written by E.J. Harrison. Shortly after, Alan began practicing Judo assiduously in a local dojo.

At age sixteen, he discovered Harrison’s follow-up book on Karate. However, there were no Karate instructors in Ireland at the time so Ruddock set up a makiwara in his parent’s garden and taught himself and a few school friends the rudiments of Karate.

Alan founded the very first Karate organization in Ireland and affiliated it with the British Karate Federation, through which he was able to attend the classes of Murakami Tetsuji Sensei in England.

Murakami, in those early days, was an extremely tough man. If you did not understand what he said, you would receive a slap across the face to help to focus your attention!

Quickly Ruddock became quite proficient and he was graded to 5th kyu by Murakami upon their first meeting. He also invited Murakami over to Ireland to instruct his group of students.

I gave a demonstration to one of the Irish government ministers who was accompanied by an Army officer. The officer was very impressed and spoke of his interest in incorporating some Karate into their military unarmed combat.

Alan Ruddock with Higaonna Morio during a seminar in the United Kingdom.

Long after he had stopped formally practicing Karate, Alan would keep ties with the karate world and he was often invited to official events. Today, he is fondly remembered as the founder of Irish Karate and a book was even written about his pioneering years.

Murakami was a native of Shizuoka and he had learned some Aikido from Mochizuki Minoru Sensei. He showed some techniques to Ruddock, which sparked his interest. This art was unheard of in Ireland so Ruddock found a way to purchase Tohei Koichi’s book and started to study on his own, just like he had done for Karate. Ruddock understood from the book that unlike Judo and Karate, Aikido’s founder was still alive and active.

It seemed to me that Aikido was the ultimate martial art and that to get closer to the essence of it all, it was necessary to try to learn from its founder.

Kenneth Cottier, Henry Kono, and Alan Ruddock reunited many years later.

Needless to say that traveling from Europe to Japan was very difficult at the time but Ruddock was training to become a Marconi radio officer in the merchant navy, which allowed him to travel all over the world. He was eventually sent to Japan for a few days at the end of 1964. Upon disembarking, he immediately made his way to the Aikikai Hombu Dojo in Shinjuku to watch some classes. Unfortunately, O Sensei was not present on that day but Ruddock loved what he saw. He also met Kenneth Cottier and Henry Kono, two foreigners who were training at Hombu at the time. Thanks to them, Alan realized that it was feasible for a foreigner to live in Japan and he decided that he would come back to live in Tokyo and train at the Hombu Dojo.

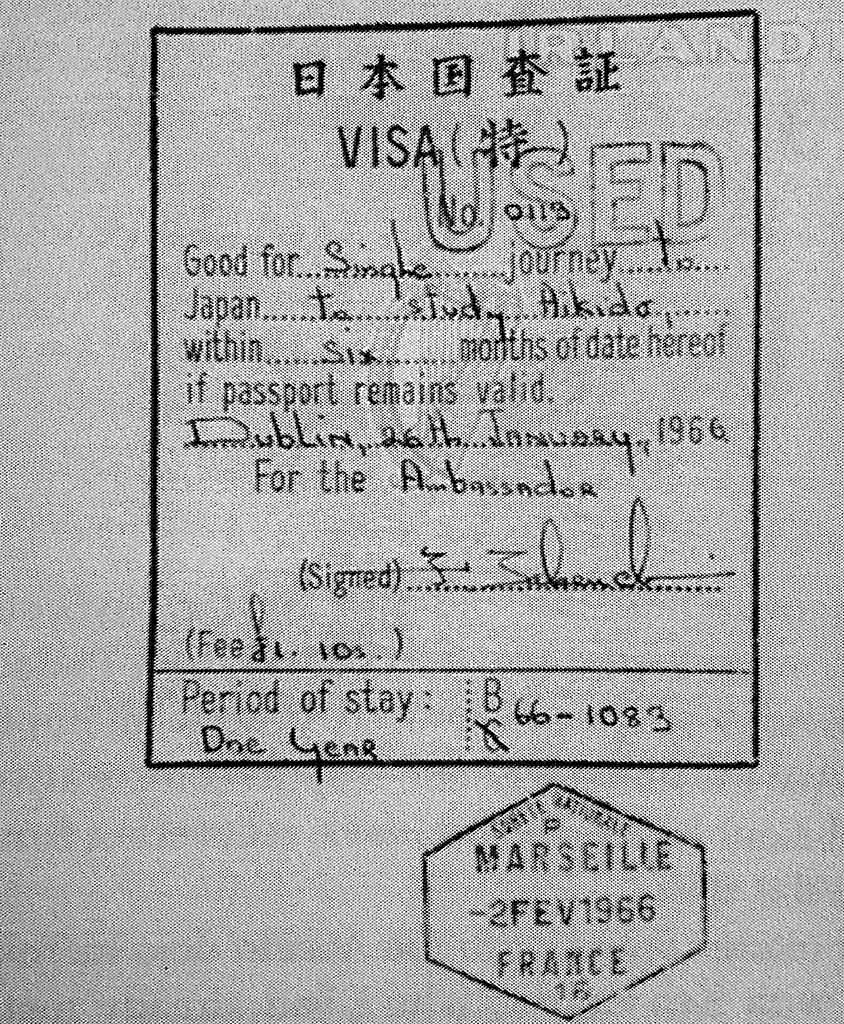

Upon returning to Ireland, Ruddock immediately started to prepare his relocation to Japan. With the help of Cottier, who wrote on behalf of the Hombu Dojo, he obtained a one-year cultural visa from the Japanese embassy in Ireland specifically to practice Aikido.

Ruddock’s visa issued by the Japanese embassy in Ireland. It states that the purpose of his stay is to practice Aikido.

There was still no Aikido in Ireland at the time but during the summer of 1965, Ruddock traveled to England to attend a course led by Nakazono Mutsuro Sensei, who had established himself in France as an Aikikai representative in 1961. Alan told me that even though he enjoyed receiving this formal instruction, it further motivated him to go learn Aikido directly in Japan.

I cannot claim that I was Alan’s closest student, but I dare say that we had a special connection through our interest in Japan. Of course many of his students had some interest in Japan or Japanese culture, but I think that he saw in me the same fire that burnt in him when he made his trip, at about the same age as I was when I made mine.

Alan was always completely honest when he spoke and he told me that he considered that Aikido had died with O Sensei. Therefore, while he understood my desire to discover Japan for myself, he did not see the point of travelling there specifically to learn Aikido. Ironically, he had not been particularly encouraged by Nakazono Sensei nor any other instructor when he decided to make his own trip. In fact, the Japanese ambassador in Ireland told him outright that he was crazy to go to Japan just to study Aikido. In the end, he never let himself be put off by this lack of encouragement and he knew that neither would I.

Ruddock in front of his house in Higashi Okubo

Obviously, when we were together, I took every opportunity to ask Alan about his time in Japan. I would often travel to attend his seminars in England and Ireland and he and I would spend long evenings drinking cups of Irish black tea and talk about life in Tokyo and the classes at Hombu. His stories definitely crystalized my perception of what life with Japanese people might be like.

Alan’s visa was issued on January 26th 1966 and he embarked on the ship “Le Vietnam”, which sailed from Marseille on February 2nd.

Six weeks after leaving Marseille, Ruddock disembarked in the port of Yokohama. He was welcomed there by Kenneth Cottier and by John Gallon, a fellow Englishman who practiced Judo at the Kodokan from 1966 to 1971. They arranged an accommodation for Ruddock in Akabane and helped him settle.

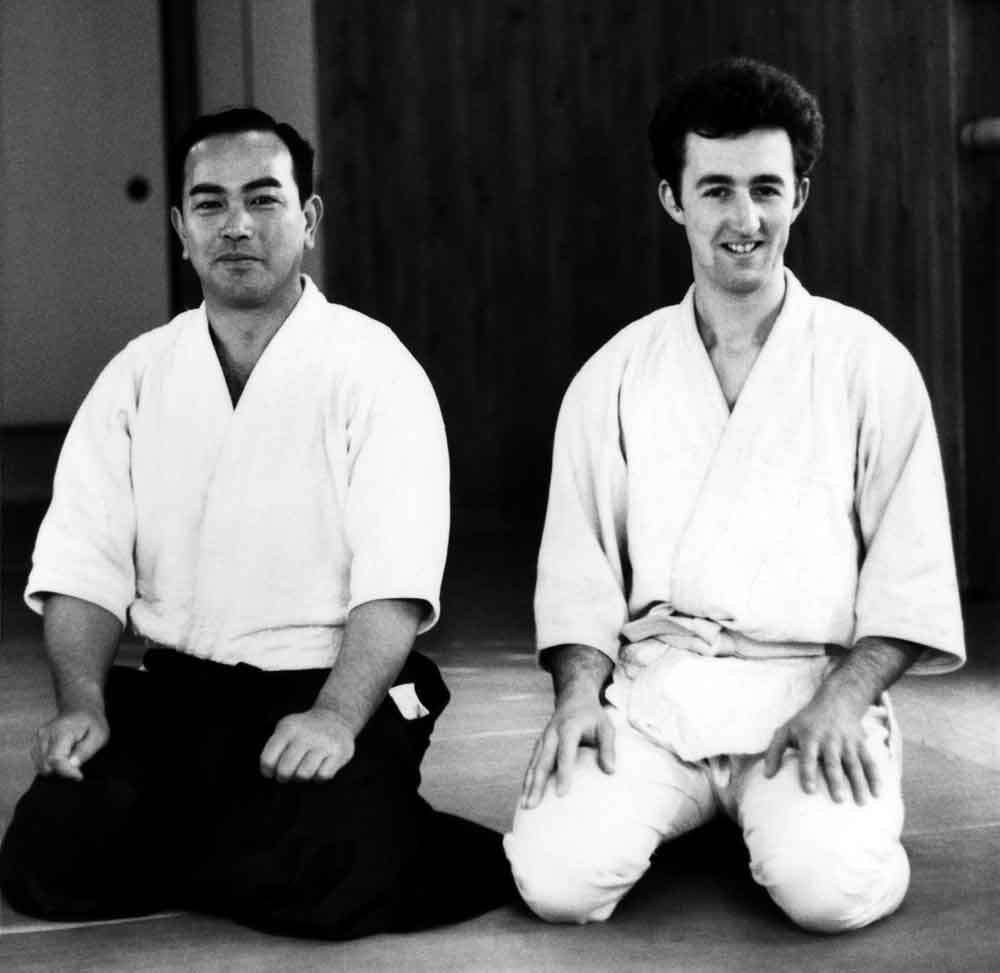

Alan with Kobayashi Yasuo Sensei in Hombu.

Alan made the trip every day to train at Hombu but having been brought up in a rural country like Ireland in the nineteen fifties, he found it difficult to deal with the big crowds in Tokyo, especially commuting in packed trains. He therefore promptly moved to a different accommodation close to Hombu Dojo, in Higashi Okubo.

Alan was the only foreigner there whose visa explicitly stated that he was here to practice Aikido and as a result he trained intensively every single day.

There were two lessons in the early morning, one class at three o’clock and one last class in the evening. On Sundays there was just one session instructed by Saito Morihiro Sensei. Alan also had private lessons once a week at 10 o’clock in the morning, first with Kobayashi Yasuo Sensei and later on with Ichihashi Norihiko Sensei.

Alan with Tohei Koichi Sensei in Iidabashi

He also attended Tohei Koichi Sensei’s classes in Iidabashi and Nishio Shoji Sensei’s classes in Otsuka. As a karateka, Alan particularly appreciated Nishio Sensei’s percussive style.

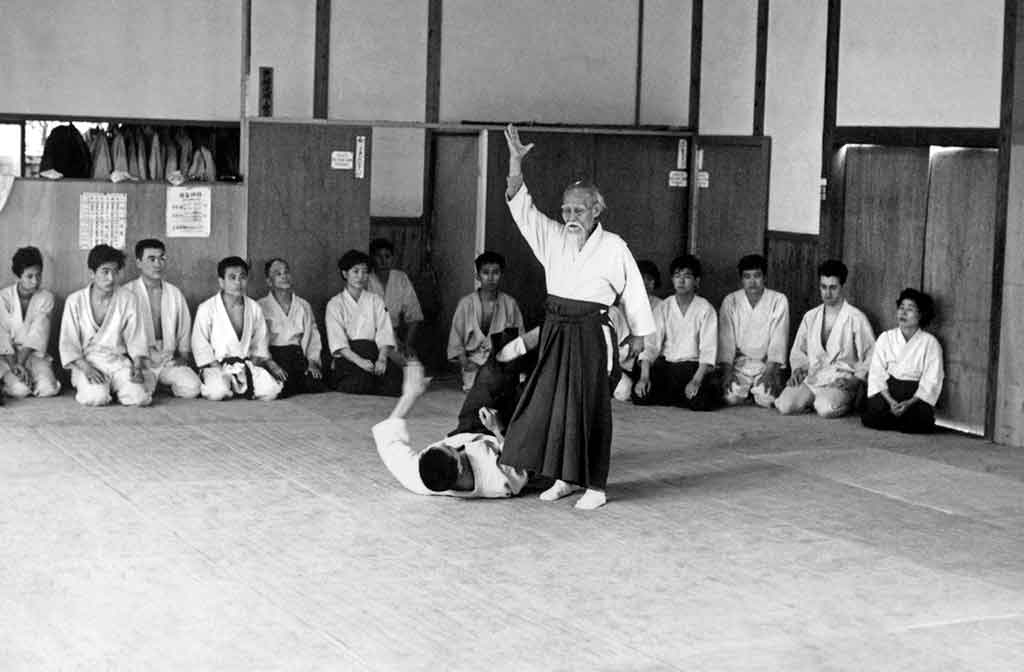

Alan had come to Japan specifically to train with O Sensei and during his three-year stay in Japan, Alan reported seeing him teach close to two hundred times.

When I first saw O Sensei in action in the dojo, I paid very respectful attention to what was going on. I did not think it was supernatural or magical, it all seemed too easy. As a former judoka and karateka I was wondering what this man was doing that made things appear so simple. That was the focus of my attention.

O Sensei teaching. Alan is at the back, second from the right.

Each time Alan talked to me about practice at Hombu at the time, he insisted on the fact that the atmosphere was quite relaxed, and that the etiquette was much less formal than what we see in most dojo today. In fact, he seemed to think that especially when it is practiced in the West, etiquette can get in the way of learning.

One thing he also insisted upon is that from his first day, he became convinced that O Sensei was doing something different compared to everyone else at Hombu.

It was obvious to the intelligent observer that what O Sensei was doing did not fit in with “normal” practice.

Class at the Hombu Dojo. Alan Ruddock is the seventh from the left.

That being said, Ruddock said that every teacher was showing things differently and that O Sensei did not seem to mind those different interpretations. Alan used to instruct me to watch me old VHS tapes of O Sensei and he insisted that if I wanted to understand what he was doing, I had to find out what he was doing differently from other people.

Aikido is not an art of doing, it is an art of knowing. If you know what to look for, you will know what to do, and your body will move properly.

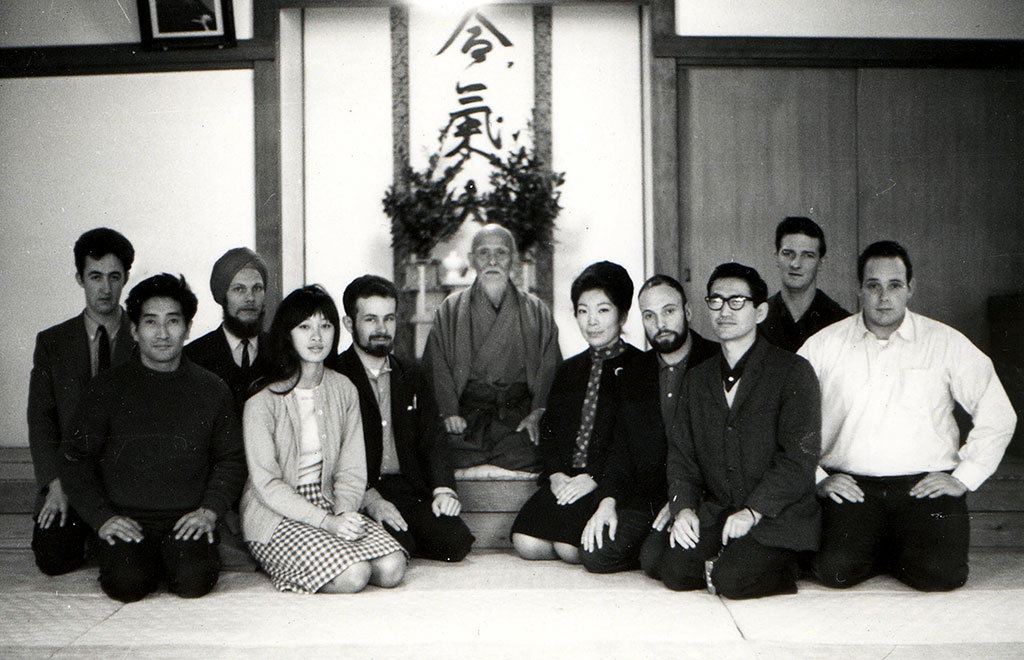

O Sensei surrounded by the group of foreign students. From left to right: Alan Ruddock, Henry Kono, Per Winter, Joanne Willard, Joe Deisher, O Sensei, Joanne Shimamoto, Kenneth Cottier, a visitor from the USA, Norman Miles and Terry Dobson (photo taken by Georges Willard with Henry Kono’s camera).

The number of foreign practitioners at Hombu was quite limited and they formed a tight group of friends. They had relatively easy access to O Sensei and several of them like Henry Kono or Joanne Shimamoto spoke Japanese, which allowed them to ask questions. Ruddock had read an English translation of the Kojiki so he was actually able to understand some of the more esoteric talks of O Sensei.

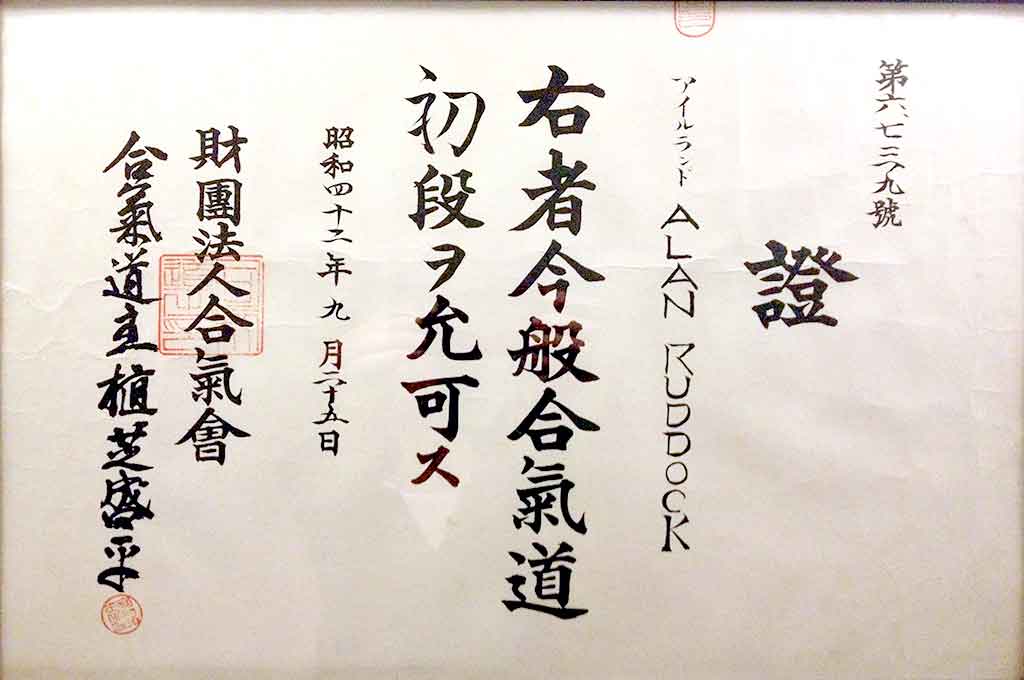

Ruddock had received very little instruction in Aikido before settling in Japan so in many respects, he was a pure product of the Aikikai Hombu Dojo. He learned from all of the teachers and got inspired by O Sensei. In October 1967, he was awarded the shodan.

Alan was present at Hombu at a crucial time since the new concrete building was being built. He was therefore part of the last generation of students who trained in the old Kobukan Dojo.

Alan Ruddock’s shodan certificate. It is dated from the 25th of September, 1967 and is signed by “Aikido Doshu Ueshiba Morihei”. Interestingly, it also bears the mention that Alan is from Ireland. The certificate is numbered 6739.

After nearly three years, Alan left Tokyo in fall 1968. On his way back to Ireland, he stopped by Hong Kong for a few months, where he helped fellow Hombu practitioner Virginia Mayhew run the Hong Kong Aikikai, which she had founded in 1966.

There was no Aikido in Ireland and Alan was not interested in establishing an organization. He started teaching his former Karate associates and it grew from here.

I travelled through London and briefly met Chiba Sensei. He brought me to a pub, bought me a pint of Guinness and proceeded to thump the table while telling me that real Aikido was not in Japan, because they were all going soft. I then knew that I was on my own.

Alan Ruddock and Henry Kono in front of the old Hombu Dojo. Behind them is a poster presenting the upcoming new building.

He continued to practice along with other Aikikai-affiliated groups and teachers but slowly, he realized that he was no longer interested in being part of a large worldwide organization and he eventually broke off.

Alan had a no-nonsense approach to Aikido with no misplaced sense of etiquette and authority. His classes were very informal and friendly. Having been at the Hombu Dojo all that time, he knew the rules better than most, but he operated in the way that Ichihashi Sensei advised him when he left Japan: “Remember, all these things we do like bowing and sitting in seiza are Japanese, not Aikido. When you return home, teach Aikido your way”. That is what he did.

Like many other teachers, he thought he had understood something that others did not and his technique was definitely very personal. Although anyone who wished to train with him was welcome, he made no particular efforts to get people to join him. My understanding is that he left the Aikikai at some point in order to be freer in his teaching and to avoid friction with other representatives.

Others do SMASH-kido, I do Ai-kido

Alan Ruddock teaching in Galway in 2001. Sitting at the forefront is Guillaume Erard.

Alan later set up his own organization called “Aiki no Michi” based on the late calligraphy of O Sensei. He received the 6th dan from the Dai Nippon Butokukai and awarded his own dan grades to his students independently. Alan reunited with Henry Kono in 1995 and they taught a yearly joint seminar in Galway, on the West Coast of Ireland. I received the first and second dan from Alan during those summer camps.

After I moved to Japan, our contacts became more irregular but we still exchanged emails and letters.

Guillaume, I am delighted to hear that you are enjoying Japan and learning Aiki-jujutsu […] but I think that this may not help you much if you want to understand what O Sensei was doing when I saw him.

I always held in my mind that once I had learned enough about Aikido, done enough physical training, and worked my body enough, I would return and focus my study to understand what he did. Sadly, his untimely passing in 2012 made this impossible.

Note: Many of the pictures shown in this article were taken by Henry Kono. A large number of those were used in various Aikido books over the years but he was only seldom credited.

To learn more about Alan, in his own words, you can read an interview I did with him back in 2008.

About the author

Guillaume Erard

Guillaume Erard is an author and educator, permanent resident of Japan. He has been training for over ten years at the Aikikai Headquarters in Tokyo, where he received the 6th Dan from Aikido Doshu Moriteru Ueshiba. He studied with some of the world’s leading Aikido instructors, including several direct students of O Sensei, and has produced a number of well regarded video interviews with them. Guillaume now heads the Yokohama AikiDojo and he regularly travels back to Europe to give lectures and seminars. Guillaume also holds the title of 5th Dan in Daito-ryu aiki-jujutsu and serves as Deputy Secretary for International Affairs of the Shikoku Headquarters. He is passionate about science and education, and he holds a PhD in Molecular Biology. Guillaume’s work can be accessed through his website and on his YouTube channel.