[Monthly column] Worldwide Koryu Dojo Report Vol.13 Shinto Muso-ryu Jo in Geneva, Switzerland

Interview and text by Grigoris Miliaresis

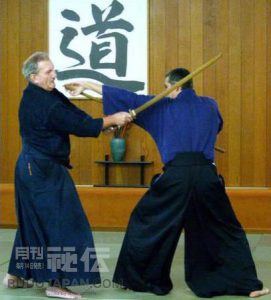

Tanjo irimi

Pascal Krieger, featured in this 13th Worldwide Koryu Dojo Report is the reason jodo exists in Europe. A student of Don Draeger and Shimizu Takaji, Geneva-based Mr. Krieger has been disseminating Shinto Muso-ryu since 1976 and in 2008 was awarded the Order of the Rising Sun by the Emperor of Japan.

Pascal Krieger iai Jodan no Kamae

Dojo ID

Name: Shung-Do-Kwan Budo

Location: 66, rue Liotard, Geneva, Switzerland

Foundation year: 1947

Arts practiced: judo, aikido, karate, kendo, jiujutsu, iaido, jodo, Yoseikan Budo, kyudo and shodo

Local affiliation: no affiliation

Japan affiliation (instructor/organization): no affiliation

Instructor’s name: Pascal Krieger (iaido, jodo, shodo)

Instructor’s credentials/grades: judo 4th dan, Co-director of the European Iaido Federation (EIF), Shinto Muso-ryu Jo Menkyo Kaiden, shodo Shihan

Number of members: about 78

Members advanced/beginners ratio: 40/60

Days of practice/week: iaido 2, jodo 3, shodo 1/month

Website/social media/email: https://sdkbudo.ch/ contact@sdkbudo.ch

1) When and how did you get involved with the classical arts you practice?

With Kaminoda sensei in front of Shimizu Sensei’s grave, 2009

I arrived in Japan in March 1969 and practiced judo at the Kodokan. There I met Don Draeger sensei who encouraged me to try classical martial arts and introduced me to Kuroda Ichitaro sensei (iai and shodo), Shimizu Takaji sensei (jodo) and Kaminoda Tsunemori sensei (iai, jo). I continued practicing judo daily but also practiced iaido, jodo and shodo several times a week. In 1972, Draeger sensei asked me to help him edit “Martial Arts International” in Chicago; because of the 1973 oil crisis, he sent me to Hong Kong to continue but the project was eventually abandoned. Having no money, I returned to Japan and continued practicing until 1976.

2) How widespread are the classical arts you practice in your country? How about classical arts in general?

When I returned to Switzerland, European Iaido Federation Director Malcolm Tiki Shewan had began spreading iaido in Europe and I joined him. Jodo, was totally ignored so I started slowly spreading it first in Geneva, then in Switzerland and later in France, Spain, Italy, Hungary, Czech Republic, Netherlands, Germany, Portugal, Ukraine and Russia. I created European Jodo Federation in 1979 and gradually appointed well-trained people in charge in each country and held European gasshuku twice a year, once in Geneva and once in each country; at the same time, most of the appointed teachers were giving regular gasshuku in their countries.

Kagamibiraki meeting in Geneva, 2008

3) Do you and the members of your group travel to Japan to practice?

With Nishioka Sensei and his wife in front of the Kamakura Buddha, 2009

We went to Japan twice for a big Shinto Muso-ryu seminar. In 1980, I invited Draeger Sensei, Kaminoda Sensei and Katori Shinto-ryu’s Otake Ritsuke for an one-month stay in Europe; Kuroda Sensei was also invited a few years before that. After Kuroda Sensei, Shimizu Sensei’s and Draeger Sensei passed, I decided to follow Nishioka Tsuneo Sensei: We invited him several times for long periods in Europe and continued to follow him until his death. In shodo I continued studying remotely with Kuroda Sensei and when he died (2000), I was directed to the head of Toka Shoin, Saito Isoji.

4) What is the biggest difficulty in practicing classical Japanese martial arts?

Kusarigama at Matsumoto, 2009 (photo: Jacques Bally)

Kata practice is the hardest to explain to Europeans: repeating the same movements over and over was not much appreciated by most -they wanted free sparring. Gradually, I convinced them that repetition allows you to apply classical martial arts principles like maai, zanshin, kiai etc. that cannot be experimented in free training; eventually most practitioners became familiar with them.

5) What is the difference between practicing classical and modern Japanese martial arts?

The big difference is that in modern martial arts (except perhaps aikido), victory over the other is the main goal. Kata practice offers a different victory: over oneself. The best example is iaido: with no enemy in front of you, you are alone with your problems and you must work on them to do the technique properly. In classical arts, there is more respect –for your partner, for your training space etc. Another interesting point in classical martial arts is that we repeat very old principles, some coming from 14th century Japan, and we have to re-actualize them in our world and continue developing them. I like the saying “tradition is tending the flame, not worshiping the ashes”.

6) What is your arts’ strongest characteristic, historically or technically?

Training at the Shung-Do-Kwan with Lorenzo Trainelli

Shinto Muso-ryu concentrates on jo versus sword. The jo’s three advantages over the sword -length, 360° trajectory and double-end use- allow it to deal with the sword effectively. Furthermore, through the adoption of other arts like Isshin-ryu kusarigamajutsu, Shinto-ryu kenjutsu, Uchida-ryu tanjojutsu and Ikkaku-ryu juttejutsu, Shinto Muso-ryu practitioners train how to engage in different distances while respecting jo principles like look (metsuke), seichusen (vertical alignment), hyoshi (rhythm) etc. It is indeed a very rich art taking a whole life to perfect.

7) What is the benefit of practicing classical Japanese martial arts in the 21st century – especially for someone who isn’t Japanese?

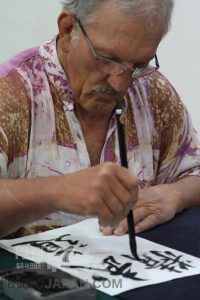

Shodo demonstration in Penang, 2015

Classical budo study has been a constant enrichment. It helped me center myself and better understand Japanese culture; teaching it to Europeans who know nothing about Japan is a very enriching experience. Regular training keeps me fit and in harmony with myself. For example, holding a sword, jo or even a shodo brush has similarities: you don’t move them with your arms but with your whole body. Classical budo taught me how to breathe and the three different rhythms Sho, Chu and Go: Sho is like script style, one movement at a time and comes from the mind, Chu is rounder, flowing, like calligraphy’s gyosho style and comes from the heart and Go comes from the hara, with power and speed.

Of course classical martial arts study is teaching foreigners Japanese culture. In the beginning it is totally strange for us until we start finding similarities with our cultures. Japan is part of the world so it’s normal to relate its culture to others, even if it’s quite different at first glance. Japanese culture has given me a lot, especially through practice; there’s a phrase from Confucius that goes “what I hear, I forget, what I see, I remember, what I do, I understand”. It is through practice that we can understand Japan’s wonderful culture and I will continue it until my last day.

Kagamibiraki 2010, Geneva

8) Is there a Japanese community in your city? Do you have any connections to them and to other aspects of Japanese culture?

Shodo seminar, 2012

There aren’t many Japanese in Geneva: a sushi restaurant, a calligraphy equipment store or a budo equipment shop is the extent of it. There’s a Consulate of Japan organizing a yearly event where all Japan-related parties are invited; one consul was so happy with my work in disseminating Japanese culture that arranged for me to receive the Kyokujitsu Sokosho (Imperial Order of the Rising Sun) in a ceremony with more than a hundred guests! I also brush Japanese characters in various occasions, have several Japanese shodo students and demonstrate iai, jodo and shodo in the annual Japanese festival.