I was wrong about kendo: thoughts on Japan’s most emblematic budo–70th All-Japan Kendo Championship

Text by Grigoris Miliaresis

I was wrong about kendo: thoughts on Japan’s most emblematic budo

Nippon Budokan the day of the 70th All-Japan Kendo Championship.

The idea that to comprehend the real value of a cultural phenomenon you have to see it in the context of the culture that created it isn’t exactly original; as a matter of fact it is self-evident. It is surprising though how often we forget it and we spend our time and energy trying to analyze aspects from cultures very different from ours while separated from the systems that created them; especially when said cultural systems are very different from ours, our analyses become at best limited and at worst completely misguided. What is even more surprising is how often this happens even when we have some idea about that culture and other aspects of it.

“Hiden” readers already know that Japanese martial arts are an important part of my life and my career: I have been reading about them since 1977, I have been practicing them since 1986, I have been writing and translating about them since 2000 and with a broader interest in Japan pushing all the above I think of myself as having some knowledge above average when it comes to this country’s martial traditions. Still, I had to move to Japan to understand how important kendo is for the country, its society and its people.

70th All-Japan Kendo Championship Opening Ceremony (Photo: Grigoris Miliaresis)

The irony is that I had in fact practiced kendo for a couple of years before I moved to Japan: the dojo I had been practicing iaido for 4-5 years at some point, and because of pressing demand from various students (including me!) started a kendo class and I was one of the first students. Even then, though, my understanding remained limited: I immediately realized how good a practice it is from a physical standpoint and how many useful tools it offers for other martial arts and for daily life (explosiveness, fast evaluation of distance, reflexes etc.) but I couldn’t fathom the specific weight kendo carries in Japan.

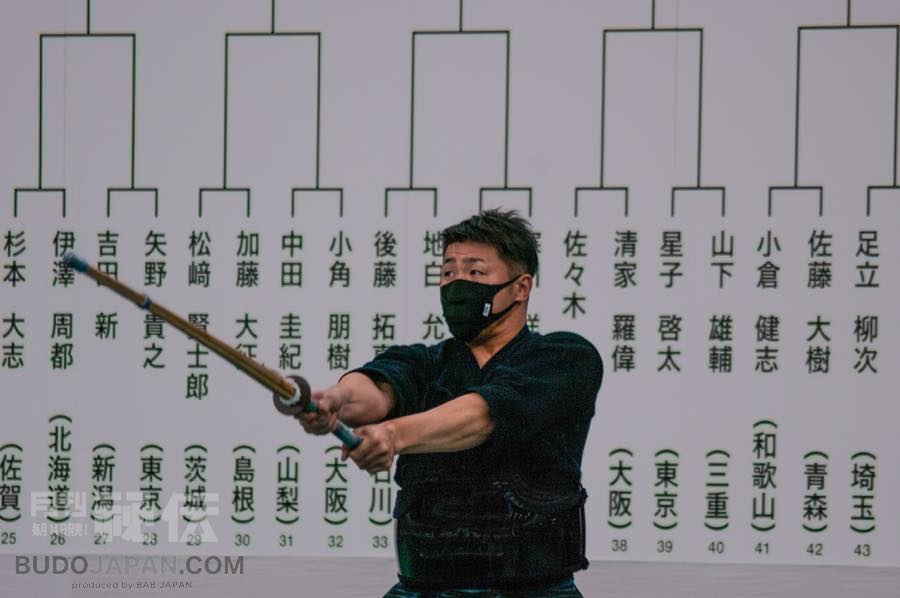

Last minute practice in front of the tournament bracket (Photo: Grigoris Miliaresis)

It’s everywhere!

This realization came almost immediately after I came to Japan: to summarize it, for the Japanese the word “budo” i.e. “martial arts” means “kendo” –simply and unequivocally. Yes, there are eight more arts designated by the state as “Nihon Budo” or “Japanese martial arts” -judo, karate, aikido, Shorinji Kempo, sumo, kyudo, naginata and jukendo- but you very soon realize these arts are not equal in the minds of the majority of the Japanese. “Judo” means “Olympic sport”, “sumo” means “professional sport”, aikido, naginata, jukendo and Shorinji Kempo are known only to those practicing them and extremely fragmented, karate walks a tightrope between its Okinawan roots and its modern sportive/Olympic incarnation.

Nippon Kendo Kata Demonstration (Photo: Grigoris Miliaresis)

What remains? Kyudo and kendo distributed between women (mostly) and men (almost exclusively) and because Japan is still a patriarchal society, kendo is way ahead –to the extent that it has alone, about twice the number of practitioners of all the other arts combined. There is no school -elementary, junior high or high school- no university and no big company that doesn’t have a kendo department with a teacher who is at worst a 5th dan and with a space for practice that is either owned or permanently leased. There is no neighborhood in the big cities or town anywhere in Japan without a shop selling kendo equipment and there is no ward or prefecture that doesn’t hold some type of kendo tournament or championship.

Changing shinai because of broken string (Photo: Grigoris Miliaresis)

What’s even more amazing is how all this reflects in society: in my 13 years in Japan, I have never met one Japanese, regardless of sex, age, education level, professional field or place of residence who doesn’t know what kendo is and doesn’t understand at least its basics. And, even more so, who doesn’t believe that kendo is the completely natural and historically legitimate evolution of the country’s martial history and samurai culture, regardless of the fact that a kendoka and his weapon only marginally and with a liberal dose of imagination brings to mind Japan’s 11th-19th century warriors and their swords.

Waiting for the judges’ verdict (Photo: Grigoris Miliaresis)

In koryu too

The above was particularly shocking for me as a practitioner of classical martial arts: like most koryu people abroad, I was under the impression that these arts exists in a parallel universe that has little to no relationship to modern budo. What really happens is that kendo is the main pool from which classical schools draw their membership and that isn’t limited to kenjutsu schools that have an obvious historical relationship to it. Spear schools, staff schools and even naginata schools are greatly manned by people with experience and some past in kendo and these people often keep their relationship with kendo parallel to their involvement with their classical school. And very often (not always but this is something best left for a future discussion) the transfer of knowledge and skills from kendo breaths new life in these schools.

Finding an opening from below (Photo: Grigoris Miliaresis)

In my case, this point was driven home in both the schools I am studying: the 20th soke of my naginata school (Tenshin Buko-ryu Heiho), Yoichi Nakamura was a kendoka and that made his naginata technique even more alive. As for my sword school, Ono-ha Itto-ryu, it has a relationship with kendo so deep that trying to separate them would be historical revisionism! And I’m not talking Edo Period gekiken here: from the last three generations of Ono-ha Itto-ryu heads (Junzo Sasamori, Takemi Sasamori and Yuji Yabuki), two were/are top level kendoka and the third had also practiced kendo for several years and his thoughts on how Itto-ryu benefits kendo had been often featured in kendo magazines. Today, at least 60% of the school’s practitioners are kendoka and despite the popular misconception, their kendo hasn’t weakened their Itto-ryu: it has made it stronger!

Finding an opening from above (Photo: Grigoris Miliaresis)

(Not being a sociologist I won’t get much into it but I think there is a social aspect that shouldn’t be overlooked: consensus is very important in Japan which means being accepted is very important which means mainstream activities are important –ask any male office worker what they think about golf. As koryu are certainly not mainstream even for the Japanese, a connection with kendo makes people more accessible and their activity more easily appreciated and, dare I say so, more respected.)

The best of the best

One of the reasons I am enjoying life in Japan so much is that new discoveries are always around the corner. In the case of kendo, my biggest so far and the one to bring together my understanding of kendo came last November, on the 3rd and at the Nippon Budokan where the 70th All-Japan Kendo Championship was held; if the name isn’t enough to realize the importance of the event, I’ll add that it is the most prestigious kendo event in Japan (and consequently in the world –yes, more than the World Kendo Championship), it comes with a cup from the Emperor, presented by a member or the Imperial Family (this year it was Princess Yoko of Mikasa) and it involves sudden death matches between Japan’s 64 best kendoka that come from qualification tournaments held in all Japan’s prefectures.

Semi Final, Takayuki Yano vs Sho Ando (Photo: Grigoris Miliaresis)

Like most martial artists I had seen matches from the AJKC before. But I can now say with utmost certainty that there is a huge gap between watching that level of kendo from a video and watching it live and especially through a telephoto lens, trying to catch the exact moment something happens (that’s a personal bet: avoiding continuous shooting as much as possible). This time and thanks to going there with “Hiden” for the purpose of this here article, I was able to do exactly that and from the closest distance to the action after the referees and it proved to be a, well, eye-opener.

Semi Final, Toranosuke Ikeda vs Tetsuhiko Murakami (Photo: Grigoris Miliaresis)

One of the main criticisms towards kendo is that with the focal point of all practice being winning a match and then a tournament and then a championship, it is not a martial art but a sport; these concerns aren’t new and actually go back to the time of Nakanishi Chuzo’s Itto-ryu dojo in the 18th century when the advent of the bogu and the shinai and the increasing focus on free competitive practice over kata practice were the cause for a lot of heated discussion. This 200-year ongoing discussion (with the arguments on both sides being virtually unchanged) is the reason for the widespread belief I mentioned above i.e. that koryu kenjutsu is a sworn enemy of kendo and there is no common ground between them.

Final, Tetsuhiko Murakami vs Sho Ando (Photo: Grigoris Miliaresis)

The thing is though that kendo at the AJKC level is very much a martial art; the problem is that its detractors usually haven’t had the opportunity to actually witness it live and with undivided attention. (I’m not being arrogant here: I too only did it after over 35 years of martial arts’ practice and 13 years in Japan!) If you do, you realize that everything you would want in a real martial art is there: power, use of space and timing, strategy, psychological dominance, ability to respond to any change in circumstances, optimum use of resources, composure and presence of mind are all there, neatly bound together by etiquette as strict as you will get in any traditional Japanese art.

Final, Sho Ando’s tsuki (Photo: Grigoris Miliaresis)

My technical knowledge of kendo is not deep enough to write in detail about the development of each match and about how Tetsuhiko Murakami from Ehime, one of the 49 police officers participating in the championship (since the mid-1960s officers of the National Police Agency have been almost exclusively the winners of the event) not only climbed his way to the top position but also surprised everyone by wining over his last opponent, 32-year old ex-police officer and everyone’s favorite Sho Ando. But this is the thing with kendo: it is so ubiquitous that if you want to find out more about every step of the seven-hour long event you don’t need to look far –the final match between Murakami and Ando even made the evening news.

Final, Tetsuhiko Murakami’s men

Beyond the best (of the best)

At the top: Tetsuhiko Murakami, all-Japan winner

But speaking from the point of view of someone who isn’t a sports’ fan, who won isn’t that important: like with sumo, a martial artist can watch a match for its own sake, appreciating each kendoka’s effort and skill level and each technique’s and tactic’s perfection. And perhaps, get some inspirations they can integrate into their practice, be it in a classical art or a modern. I can say in all honesty that watching this event had this effect on me and even though adding an actual kendo practice to my schedule now is marginally impossible, I am already trying to bring something of what I saw into my current practices.

Second best: Sho Ando

Understanding why kendo holds the special place it does in the minds of the Japanese people is too complicated for an article like this because it involves historical and cultural reasons that go back to the late Muromachi Period when the martial arts’ ryu started being created and continue through the transformation of the samurai during the Edo Period and the changes brought by the Meiji Restoration and the modern era. Readers of Japanese who want to explore this phenomenon have an enormous amount of resources at their disposal whereas English speakers should start from Dr. Alexander Bennett’s “Kendo: Culture of the Sword”, arguably one of the top five books about Japanese martial arts in the English language.

Dr. Alexander Bennett watching the tournament

But even if you do not go that deep, it is important to acknowledge it does hold a special place and that it is an important piece in the puzzle that is Japanese budo which in turn is an important piece in the broader puzzle that is Japanese culture. Together with judo* (and perhaps even more than it, since kendo managed to stay away from the road roller that is the Olympic Games) it was the engine that pulled the martial arts in the 20th and the 21st century and forced classical martial artists to get out of their comfort zone, stand in front of the mirror and ask themselves how they see the future of their arts and what is worth preserving for the generations to come.

* I also believe that kyudo has a place in there as well. But we’ll talk more about that in the future!

Grigoris Miliaresis

About the interviewer

Grigoris Miliaresis has been practicing Japanese martial arts since 1986. He has dan grades in judo, aikido and iaido and has translated in Greek over 30 martial arts’ books including Jigoro Kano’s “Kodokan Judo”, Yagyu Munenori’s “The Life-Giving Sword”, Miyamoto Musashi’s “Book of Five Rings”, Takuan Shoho’s “The Unfettered Mind” and Donn Draeger’s “Martial Arts and Ways of Japan” trilogy. Since 2007 his practice has been exclusively in classic schools: Tenshin Buko-ryu Heiho under Ellis Amdur in Greece and Kent Sorensen in Japan and, since 2016, Ono-ha Itto-ryu under 17th headmaster Sasamori Takemi and 18th headmaster Yabuki Yuji.