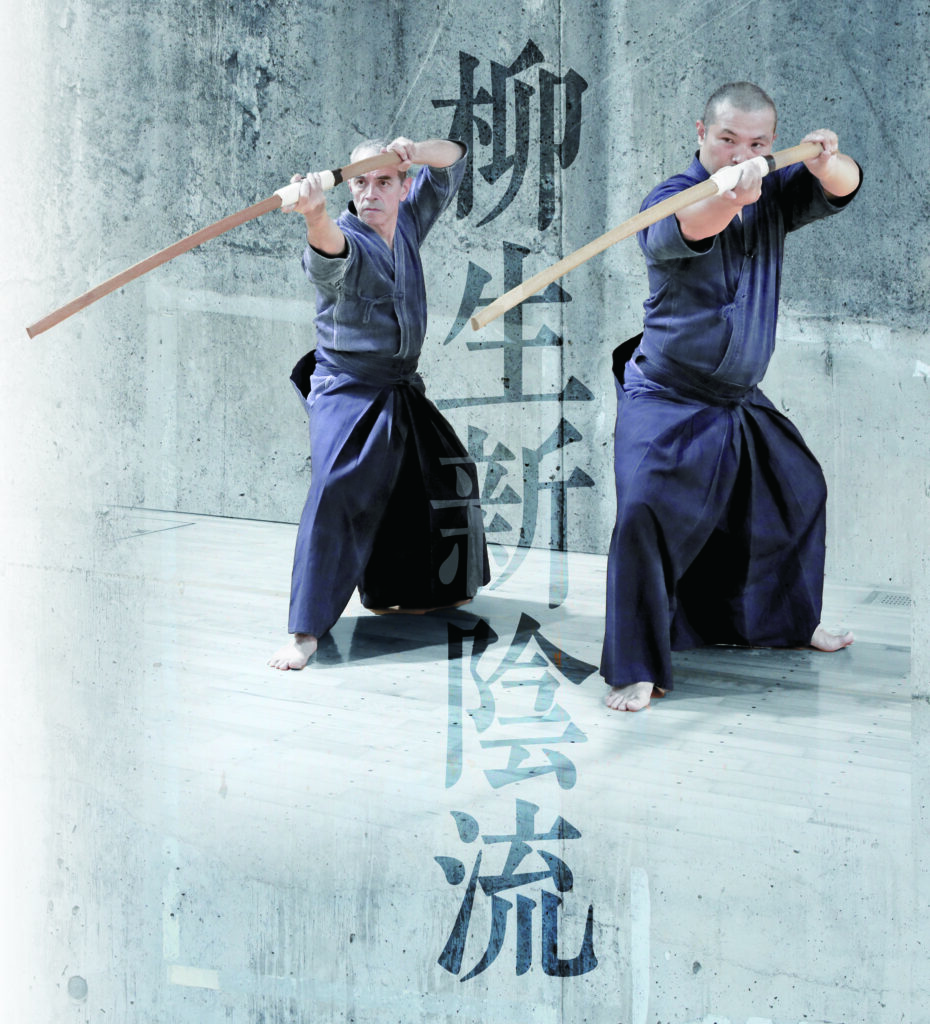

Yagyu Shinkage-ryu: In the Shadow of the Sword

Text by Grigoris Miliaresis

I don’t remember where I heard this story -and it’s probably apocryphal since I haven’t managed to corroborate it- but allegedly, when Tokugawa Hidetada, the son and heir apparent of Tokugawa Ieyasu, the founder of the Tokugawa shogunate, reached the age to start his martial arts’ training, his father told him “If someone wants to learn how to be a swordsman, they should study Ono-ha Itto-ryu under Ono Tadaaki and if they want to learn strategy, they should study Yagyu Shinkage-ryu under Yagyu Munenori; you are going to be a shogun so you should study both.” Even if it isn’t true though, this anecdote is a very good illustration of the different approaches to the sword by what are arguably Japan’s leading kenjutsu traditions and regardless where one stands in terms of personal preference, there is certainly much to be respected in and much to be learned from both.

Kage, Shinkage, Yagyu Shinkage

My readers know that my personal preference is with Ono-ha Itto-ryu: after my visit for the “Ono-ha Itto-ryu: One sword to rule them all” article, nine years ago, I enrolled at the Reigakudo under then soke Takemi Sasamori and have been practicing since. But Yagyu Shinkage-ryu has always been on my radar: it appears regularly in all major demonstrations, I have friends practicing it, back in the day I translated Yagyu Munenori’s “Heiho Kadensho” and his advisor Takuan Soho’s “Fudochi Shinmyoroku” to Greek and I have translated to English two Yagyu Shinkage-ryu series of videos produced by our parent company, BAB, so getting to see it from the inside was just a matter of time.

Of course anyone interested in Japanese swordsmanship, would want to learn more about Yagyu Shinkage-ryu: It isn’t by accident that Japan’s shogun wanted it taught to his house’s warriors and made Yagyu Munenori a hatamoto in his direct service. Its ancestor, Kage-ryu was with Shinto-ryu and Chujo-ryu one of the three original kenjutsu streams and its evolution parallels that of kenjutsu itself: from the invention of the leather-bound slated bamboo fukurojinai as a safe tool to train realistically, to the framing of a theory that included influences from Zen Buddhism and their implementation in a strategic way of thinking going beyond sword dueling and applying to virtually everything, to the early integration of shiai freestyle practice, aiming at a more rounded study of the sword.

Among the several active Yagyu Shinkage-ryu lines, we chose Nagoya Shunpukan’s Kanto dojo based in the historical town of Kamakura near Tokyo. Besides loving Kamakura, having translated the videos by the dojo’s head and chief instructor Tatsuo Akabane and his assistant instructors, shihan Daisuke Akabane and Yoko Wakao, made their approach to Yagyu Shinkage-ryu more accessible. Furthermore, as anyone who has seen their demonstrations can attest to, this interpretation, following the teachings of Shunpukan’s Kato Isao as they came from Kanbe Kinshichi, its first head and before him from Yagyu Genshu (Toshichika), tenth head of the Owari Yagyu Shinkage-ryu is quite strong –plus it contains the use of a big o-dachi sword and I certainly wouldn’t want to pass on an opportunity to try that!

The many faces of Sangaku En no Tachi

When dealing with traditions with curricula as long as Yagyu Shinkage-ryu’s (made longer because of the different ways of executing the kata: the Koden/old style, the Edo-zukai/style and the Owari-zukai/style reflecting different periods) choosing what to focus on to get a taste of the tradition is hard. By all accounts the two cornerstones of the Yagyu Shinkage-ryu system are the sets Enpi/Empi and Sangaku En no Tachi, the former handed down to Shinkage-ryu founder Kamiizumi Nobutsuna from his teacher and Kage-ryu founder Aisu Iko, and the latter handed down from Nobutsuna to Yagyu Munetoshi, so it was going to be one of the two. Since Sangaku En no Tachi only consists of five short kata (Itto Ryodan, Zantei Settetsu, Hankai Hanko, Usen Saten and Chotan Ichimi) I went with that; the names of the kata coming from the Zen text “The Blue Cliff Record” made the choice easier since I have a special interest in that Buddhism line.

Not that we could cover the whole set, though! As Daisuke Akabane sensei who was our guide for the day (unfortunately his father, Tatsuo Akabane sensei, could not attend when we visited) very thoughtfully suggested, between getting a taste of the basics that constitute the Yagyu Shinkage-ryu body (positioning, kamae, walking) and the suburi and use of the weapons (regular size-bokuto, fukurojinai and o-dachi-size bokuto), pretty much half of our time would be over so we could only focus on the first of the five Sangaku En no Tachi kata, Itto Ryodan and see how it is executed in the Edo-zukai style, the Owari-zukai style and in the Koden style. So while the rest of the class worked with Wakao sensei we focused on what is it that makes a body look, feel and function in the Shunpukan’s interpretation of Yagyu Shinkage-ryu.

The basics: standing, cutting and a dragon’s mouth

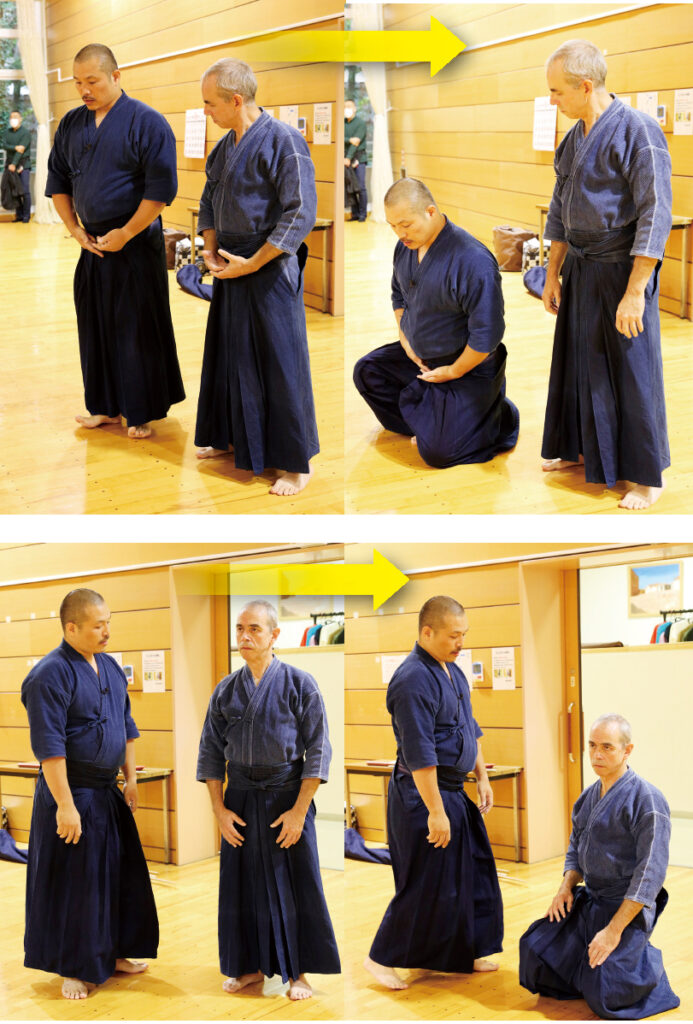

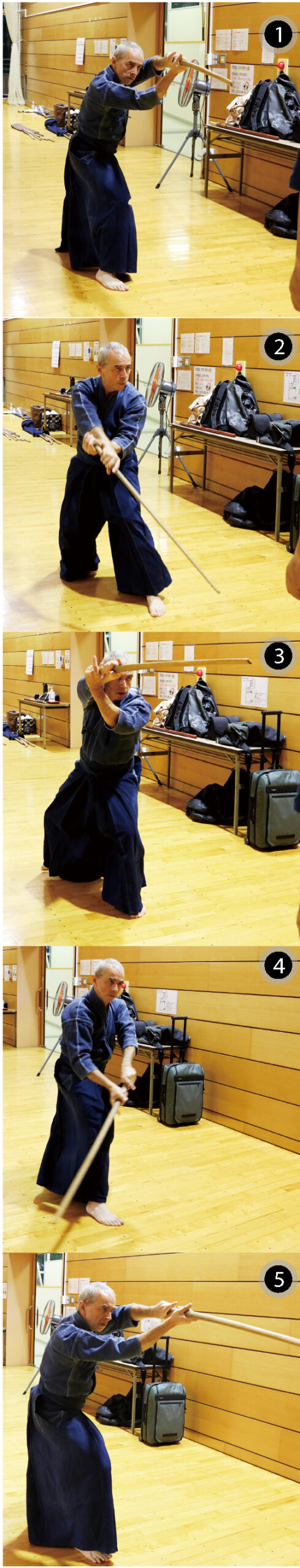

Starting from sitting by dropping the body directly downwards and standing directly upwards i.e. without oscillating the upper body back and front (these movements come up in the kata), and then to the characteristic positioning of the feet where the toes are risen lightly so the body’s weight is only placed on the feet’s arches were the first building blocks Akabane sensei demonstrated and explained; as always, intellectually understanding what needs to be done is one thing but doing it consistently without instincts from your own training kicking in, is another! The same goes for the tenouchi i.e. gripping the sword in the characteristic Yagyu Shinkage-ryu grip where the sword is positioned in line with the underside of the forearm, the wrists (but not the elbows!) rotate and the thumb and index finger create a circle called in the tradition “tatsu no kuchi” (dragon’s mouth) as well as for its sideways/hanmi body positioning, especially after cutting yokomen.

The basic suburi for loosening the body in the beginning of practice and for helping practitioners move in the low stance that comes from the dropping of the body I just mentioned, is a walking kiriage upwards cut with the left and right side alternating; the grip on the sword doesn’t change so on the one side the hands cross at the wrists in the end of the cut. To perform this correctly, the pelvis must be lowered considerably and the knees must be relaxed and function as springs that allow the sword cut strongly upwards; at the Shunpukan this movement is called “emasu” and its application in the kiriage was particularly relevant for us since this kiriage appears in the Koden execution of Itto Ryodan. Pushing the pelvis backwards and dropping the belly forward was one of the hardest parts of this experience, especially since in its ideal form, this drop doesn’t happen from the knees but from the buttocks’ and thighs’ muscles. As for the movements of the body and the sword, they start as big and slow to be able to eventually become small and fast eliminating all useless parts –no surprise there!

Sitting by dropping the body directly downwards

Raising the toes

“Tatsu no kuchi” (dragon’s mouth)

Kiriage

Starting with Itto Ryodan

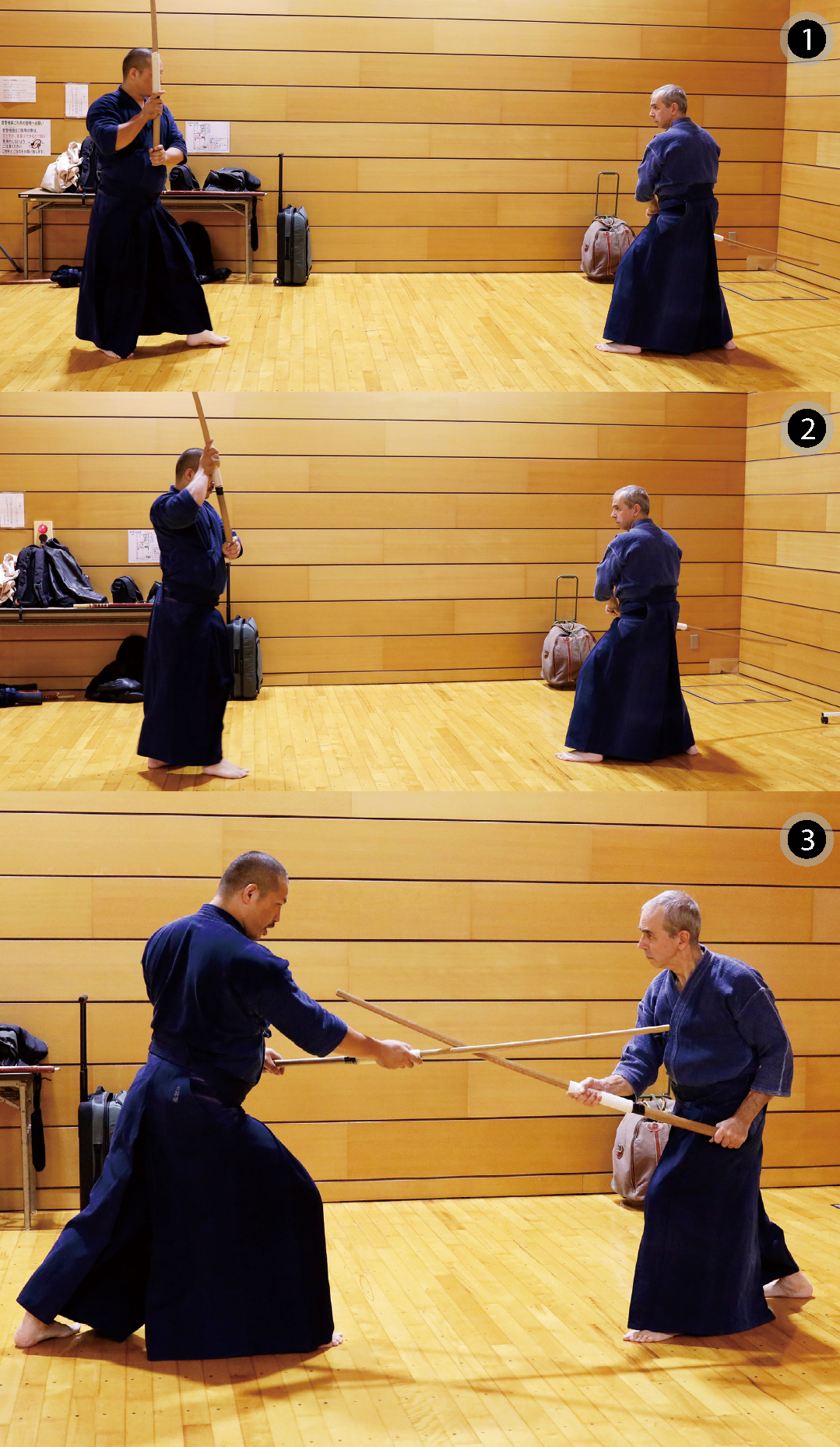

And then it was time to move to Sangaku En no Tachi’s Itto Ryodan, starting from the Edu-zukai style. The script here goes like this: from Mugyo, a mutual neutral kamae with the swords held in a very low gedan-like kamae, uchidachi takes Jun no Seigan, a seigan kamae but with the body open to the side in hanmi and shidachi responds by taking Sha no Kamae, essentially a waki gamae with the left foot forward, and exposes his left shoulder to uchidachi. Uchidachi comes to attack that shoulder with a diagonal cut and shidachi, leaving his right foot behind, turns his body on his heels with a strong twist of his hips and in an instant cuts at uchidachi’s incoming cut, landing on his sword’s tsuka or his left hand, taking his center line and making him lose his balance –to be a true Itto Ryodan i.e. a single stroke that cuts in two, the turn and the cut must be in ichibyoshi (one beat), not turn, then cut and it must be delivered at an angle that crosses uchidachi’s cutting trajectory at a right angle (this is called “winning by the character ten” which in Japanese is a cross). Uchidachi, having lost, his initiative takes one step back but shidachi moves forward with his left foot, pressuring relentlessly and keeping the same spatial relationship. Since shidachi’s body is essentially hidden behind his sword, uchidachi cannot attack it so he goes to Hasso to gain space and attack shidachi’s front/right hand and shidachi uses this open space to deliver a strike to uchidachi’s left temple cutting through the middle of his face. At that point, and to make sure uchidachi cannot attack him, shidachi’s body must be completely behind his sword, in its shadow, as it where, and since in Japanese “shadow” is “kage”, that is one way to think of the word in the tradition’s name. From there, they disengage and return to the initial neutral kamae and this concludes Itto Ryodan; as for its Zen dimension, it refers to not only cutting the opponent’s incoming attack but also cutting your own doubts, worries and thoughts in one swift, decisive movement.

To get the angles right, we first went over Itto Ryodan using the thin, light Yagyu Shinkage-ryu bokuto and then moved to the fukurojinai, the weapon most people identify with Yagyu Shiknage-ryu and the one that is used in the core of the tradition’s practice. Other than making sure that the hands stay in place and aren’t rotating on the tsuka/hilt despite the fukurojinai’s round shape, the movements are the same making small adjustments in distancing since now, thanks to the fukurojinai and uchidachi’s kote, shidachi can cut more freely than he did with the bokuto. Still, exactly because of that, it’s easy to think the strike less as a cut and more like a strike and stop the cut on uchidachi’s kote; to keep alive the feeling of cutting, the body needs to continue moving to the spot it would be if it was a live blade that had cut through uchidachi’s wrist.

After executing Itto Ryodan in the Edo-zukai style whose main characteristic is the low kamae, particularly shidachi’s Sha no Kamae, we moved to examine it in its newer form, the one Shunpukan calls Owari-zukai. Here, the main difference is that the kamae become higher and somewhat shallower (without, however, missing the fundamental elements of dropping the hips and the center) and that uchidachi comes to attack men (head) instead of left shoulder; shidachi responds to that by turning and cutting after uchidachi’s attack has been manifested, completely straight and, again, in ichibyoshi in a strike called Gasshi-uchi that rides uchidachi’s sword. The following section i.e. pressuring uchidachi and delivering the final strike which in Yagyu Shinkage-ryu is called “Ni no Kiri” is pretty much the same as in the Edo-zukai but, again from a more upright position. Like Itto-ryu’s kiriotoshi (which it resembles), the hard part in Gasshi-uchi is getting the timing right –but getting the timing right is one of the main objectives in any martial art, classic or modern.

Last came Itto Ryodan done in the Koden/old style, using the 132 cm (4.3 ft) o-dachi. This weapon has a more or less standard tsuka but the lower part/tsubamoto of its blade is not sharpened so when cutting, the swordsman’s right hand slides from the tsuka to the blade achieving better control and leverage; when handling such a big weapon, a full, strong twist of the hips is even more essential. Uchidachi, starting this time from a Hikui Seigan kamae (something like a haso but with the sword held vertically) moves towards shidachi aiming, like in Edo-zukai for his left shoulder. Shidachi does the Itto Ryodan cut but this time pulling his left hand outside his body to accommodate the weapon’s length. The pressure forward is the same, uchidachi steps back to a wide jodan (ostensibly because he is wearing a kabuto helmet) and shidachi takes one step forward with his right foot but instead of cutting Ni no Kiri to uchidachi’s temple, he cuts from below, from his chin up to his forehead in a kiriage like the one we practiced as suburi in the beginning; what’s interesting here is that shidachi can do the cut from either his right or his left side. From there, like in the previous versions uchidachi and shidachi return to Mugyo and their initial spots.

Itto Ryodan (Edu-zukai style)

Itto Ryodan (Owari-zukai style)

Itto Ryodan (Koden/old style)

Finishing with Zantei Settetsu

With some time still left, Akabane sensei thought we could also take a look at Sangaku En no Tachi’s second kata, Zantei Settetsu in the Edo-zukai style with bokuto and fukurojinai. The name literally means “cut through nails, shear through iron”, referring to cutting through any adversarial feelings towards your opponent and its script goes as follows: uchidachi and shidachi take the old Jodan kamae (a Seigan with the arms raised at shoulder level) and uchidachi moves in to strike shidachi’s sword from the left to knock it out of the way, dominate his center line and create an opening. Shidachi steps forward with his right foot, executes an uke nagashi, moves under uchidachi’s sword, cuts his right wrist and steps in and to the left with his left foot, placing his body to uchidachi’s left side and controlling his sword; all this is done in one swift move. Then, like in Itto Ryodan, he pressures forward with his left foot as uchidachi steps back and to the left to take Hasso and strike again and when this happens, he uses the opening to deliver the Ni no Kiri at uchidachi’s left temple. From there, like in Itto Ryodan, uchidachi and shidachi return to Mugyo and their initial spots; this time though, that was also the end of our introductory lesson in Yagyu Shinkage-ryu.

So what was the takeaway from this brief exposure to one of Japan’s most revered kenjutsu traditions? In a nutshell, that it certainly lives up to its reputation: there is amazing depth in Yagyu Shinkage-ryu’s approach to both swordsmanship and tactics and this is obvious even from these first and deceptively simple kata. Manipulation of distancing, timing and the opponent’s actions and reactions is essential to any martial art and in the case of Yagyu Shinkage-ryu it is honed to perfection, always keeping the invisible connection with them alive and using it as a feedback mechanism that allows the swordsman to readjust their actions constantly, drawing from the vast resource that the tradition has amassed since the times of Nobutsuna and Sekishusai. My only regrets were that we didn’t have enough time to dig a little deeper into the connection between Zen and Yagyu Shinkage-ryu and, in terms of equipment, to try the special kote (gauntlets) uchidachi uses to allow shidachi to execute their cuts with full power during fukurojinai practice.

Speaking of the fukurojinai, Yagyu Shinkage-ryu’s contribution to the Japanese martial arts’ arsenal, it is indeed easy to use so its adoption and proliferation as a training tool made perfect sense; to someone like this writer who is mostly using heavy bokuto, kendo shinai and Jikishinkage-ryu’s fukurojinai (which is completely different in terms of both construction and behavior) it felt somewhat unnatural but to be fair that is only to be expected after only a couple hours of use. What was a delight was the o-dachi offering a middle ground between the sword and the naginata, the two weapons I am most familiar with; paired with Yagyu Shinkage-ryu’s low stances and the emasu movement, it offers the practitioner not only a way to study the origins and evolution of the tradition and its techniques but also the opportunity to look deeper into body mechanics and generation of power. For that only, I would recommend to anyone in the Kanto area to arrange a visit to the Shunpukan; the awesome, in any sense of the word, amount of practical and philosophical knowledge, lore, history and tradition that comes with Yagyu Shinkage-ryu as well as Akabane sensei’s welcoming attitude and clear and precise teaching will do the rest of the convincing!

Zantei Settetsu

PS

The day we visited was particularly difficult for the Shunpukan: besides their regular practice they had to also prepare for a demonstration at Kamakura’s most revered shrine, Tsurugaoka Hachimangu coming up in a few days so the intrusion of a four-person team could only make things harder, especially if it meant keeping one of the dojo’s instructors busy for almost the full length of the practice. Both personally and on behalf of “Hiden”/Budojapan, I would like to apologize for the disturbance and reassure both Akabane and Wakao sensei and their students that their patience and tolerance was deeply appreciated.

Grigoris Miliaresis