Gekiken – A bridge between old kenjutsu and modern sport Kendō

Text by Sandro Fruzi

Searching for samurai sword

Sandro Fruzi

Twenty-five years ago, when I first decided to learn the way of the Japanese sword, I visited various martial arts dōjō, searching for a school that would suit my personality. Since I had no knowledge about Japanese martial arts, the only way to research some info was through books, articles, and friends who were practicing. What my 14-year-old self was looking for, was a place that combined the handling of a samurai sword (kenjutsu) with the real application of techniques learned in kata (form) through a free sparring practice. However, I soon learned that the art known today as kenjutsu had nothing to do with the free sparring practice done with a bamboo sword (shinai) while wearing a body armor (bōgu). That discipline was called Kendō, or so I was told. Not only were the worlds of kenjutsu and Kendō separate, but I could also feel that the two disciplines did not acknowledge each other. As a result, I began learning the basics of Japanese swordsmanship with bokutō (wooden sword), shinai (bamboo sword), and iaitō (unsharpened blade made from an aluminum-zinc alloy) in an unnamed dōjō, where everything was combined into a single practice. However, as time passed, I realized that these three elements I had expected to converge toward the same goal lacked a common ground.

gekiken

Things changed when I enrolled in the Oriental Studies Department at the University of Rome, pursuing a major in Japanese language and literature. Taking classical Japanese classes, I became interested in scrolls and martial arts books from the feudal era, especially the Edo period (1600-1868). Some of these documents contained illustrations showing practitioners wearing protectors that looked very similar to the bōgu, the body armor used in modern Kendō, engaging in striking practice and grappling techniques. What surprised me the most, was their attempt to unbalance each other with techniques that resembled Jūdō or jūjutsu. Accompanying these illustrations were detailed explanations in mixed kanji (Chinese characters) and kana (Japanese syllabary).

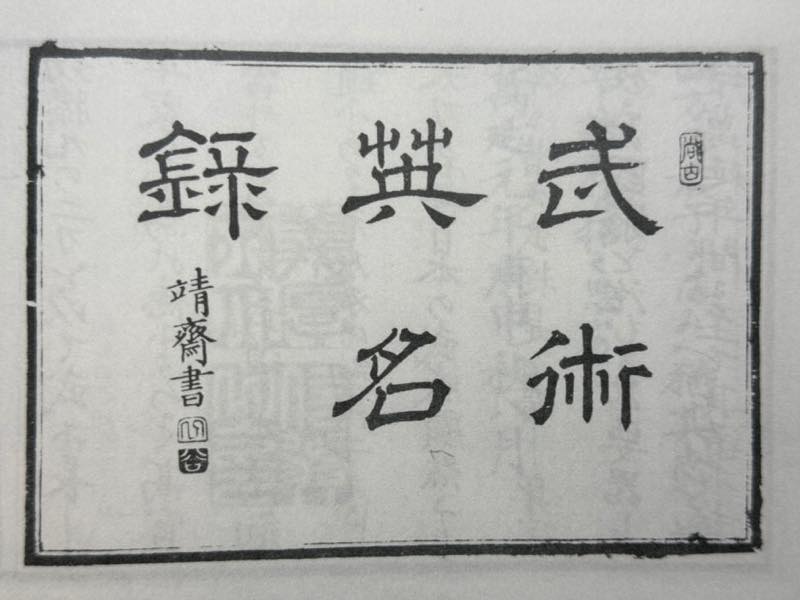

Koukoku Bujutsu Eimeiroku(Kumiuchi)

Trying to decipher every scroll I could put my hands on, I learned that free sparring practice known as gekiken (literally ‘striking with swords’), which I had considered a characteristic of modern Kendō, was actively practiced in the Edo period, and that many traditional schools established during the Muromachi (1336–1573) and Azuchi-Momoyama (1573-1600) periods were involved in free sparring practice and inter-school matches, the so-called taryūjiai. Some readers may find this statement suspicious, especially those who are enrolled in ancient schools where gekiken and taryūjiai are strictly prohibited. However, when examining documents from the end of the Edo period, doubts about this stance naturally arise.

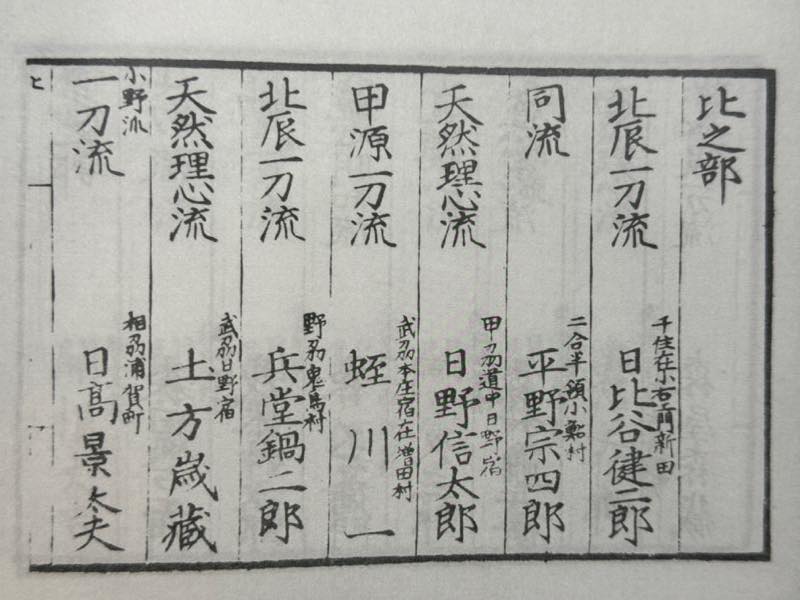

For example, let’s have a look at the Bujutsu Eimeiroku (Record of famous martial artists), a guidebook for itinerant martial artists seeking places to train around the Kantō area edited by a swordsman named Sanada Hannosuke in 1860. It only features schools and swordsmen actively participating in inter-school matches fought with bamboo swords and body protectors. The Bujutsu Eimeiroku contains records of 633 swordsmen, including Hijikata Toshizō (later vice-commander of the Shinsengumi).

Bujutsu Eimeiroku 1

Bujutsu Eimeiroku 2

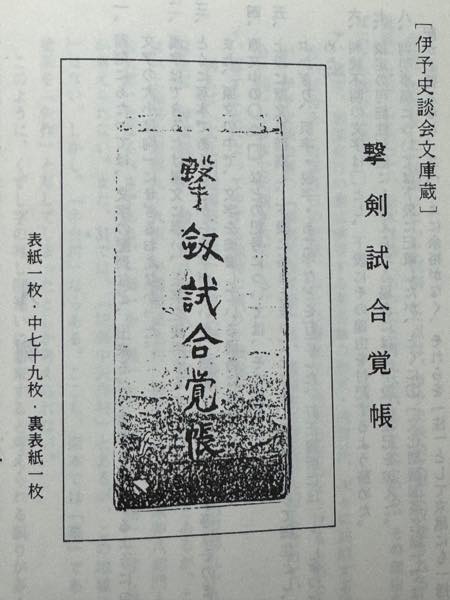

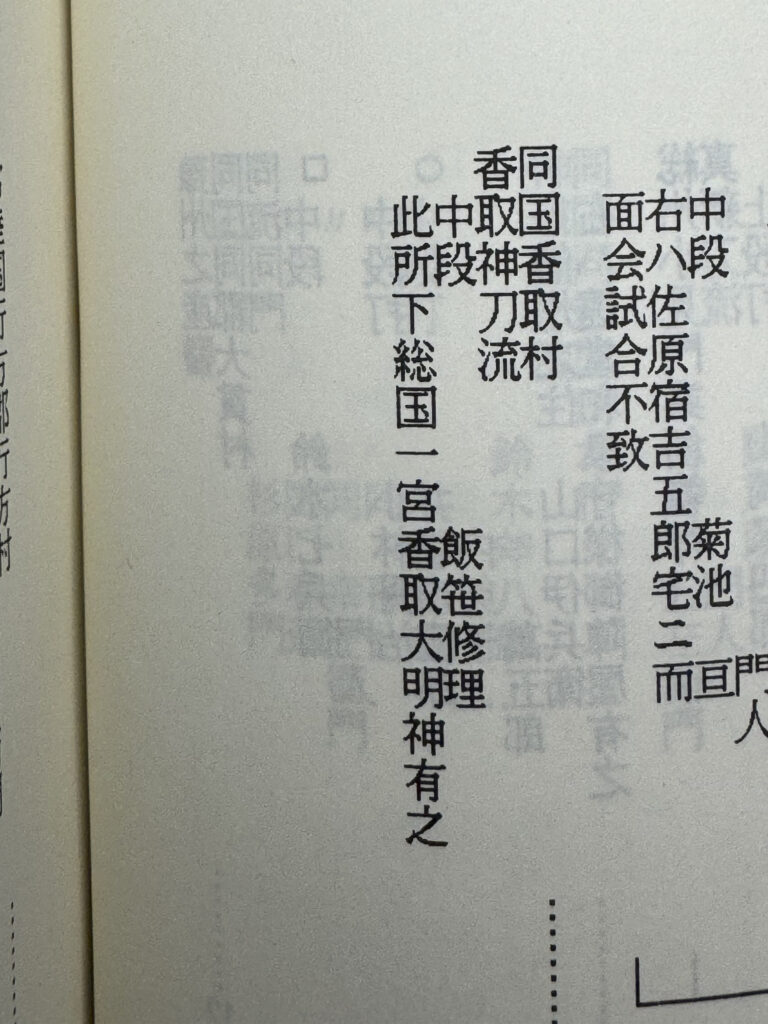

Another interesting source is the Gekiken Shiai-oboechō (Chronicles of free-sparring matches) preserved in the Iyo Historical Society’s collection, which provide us with valuable insights into the reality of taryūjiai during the Bunka-Bunsei era (1804-1830). In this document, we can see listed some of the oldest martial arts traditions like Katori Shintō-ryū and Kashima Shintō-ryū, schools that are against the free-sparring practice. With records from Kantō, Mikawa, Owari, Mino, Ise, Ōmi, Kyōto, Ōsaka, Shikoku, and parts of Kyūshū, it becomes evident that gekiken was widespread across Japan during that time, having already replaced katageiko (form-based practice) as the main form of training.

Gekiken Shiai-oboechō 1

Gekiken Shiai-oboechō 2(Kashima Shintō-ryū)

Gekiken Shiai-oboechō 3(Katori Shintō-ryū)

Tennen Rishin-ryū and Kendo

During my studies, I naturally became interested in Japanese history. Schools like Shindō Munen-ryū, Hokushin Ittō-ryū, Jikishin Kage-ryū, and Kyōshin Meichi-ryū, which revolutionized the world of kenjutsu with a focus on free-sparring practice, kept appearing in the books I was reading back then. Particularly, historical books about the Bakumatsu era and novels set in that period invariably featured protagonists belonging to one of these schools. It seemed that these great individuals had something in common: they all learned swordsmanship in a dōjō in Edo (former name of Tōkyō) and, through rigorous training, developed the strength of character that allowed them to shape the history of Japan.

The opportunity to experience a swordsmanship school from the late Edo period came at the age of 23, when I enrolled in the University of Tōkyō to finish my graduate degree. The university dormitory where I stayed at was along the Tōhachi-dōro, a road that connect Tōkyō to Hachiōji (a city located in the western portion of the Japanese capital). I was living only ten minutes away from the Hatsuunkan, a dōjō established by Kondō Yūgorō in 1876. Kondō Yūgorō was the adopted son-in-law of Kondō Isamu, the commander of the Shinsengumi, the last samurai corps of the shogunate. Kondō Isamu was also the 4th generational master of a swordsmanship school named Tennen Rishin-ryū, commonly known as the style practiced by several core members of the Shinsengumi, many of whom were born in the part of Tōkyō I was living at that time. Having read Shinsengumi related books written by Shiba Ryōtarō, one of the most famous historical novelists Japan has ever had, I decided to learn Tennen Rishin-ryū.

Back then (2008), information available online was limited (it was still the era before the widespread use of social media), so I had no choice but to visit the Hatsuunkan dōjō in person. It was only after learning from the locals that the dōjō had been closed in the ‘70s that I was redirected to Hirai Taisuke, who had learned Tennen Rishin-ryū at the Hatsuunkan under Katō Isuke, a disciple of Kondō Yūgorō. I was lucky enough to be immediately accepted by Hirai Taisuke as a disciple.

Tennen Rishin-ryū Bujutsu hozonkai enbu1

While Hirai Sensei primarily taught Tennen Rishin-ryū with a focus on katageiko, he often spoke about the gekiken of his own teacher Katō Isuke. After World War II, Katō Isuke played a significant role in preserving Tennen Rishin-ryū by including it in the curriculum of the Kendō school he was leading. The connection between Tennen Rishin-ryū and Kendō was so strong that originally the Hatsuunkan dōjō had a strict rule: that Tennen Rishin-ryū would not be taught unless a student achieved a third dan (sandan) in Kendō. However, after Katō Isuke’s passing, his successor Hirai Sensei relaxed this rule and began also instructing those who had not attained a third dan or didn’t practice Kendō at all. At that time, I wasn’t even a first dan (shodan) in Kendō. Although my daily training consisted of hundreds of swings with the bokutō and countless kata exercices, I also wore the bōgu on several occasions.

One day, while Hirai Sensei was teaching me the maai (distance) of swordsmanship, he pulled down the back of my men (head mask) from above, causing my entire body to instantly fall into a prone position. As I tried to understand what had happened, Hirai Sensei said, ‘This is shikorofuse. Katō Sensei often used this technique during his Kendō practice, along with other Tennen Rishin-ryū techniques, such as leg sweeping and throwing’. In that moment, I understood for the first time the significant difference between gekiken (and the pre-war Kendō) and modern Kendō. Unlike modern sport Kendō, a swordsman without knowledge of grappling, throwing, and leg sweeping would be at a clear disadvantage on the battlefield.

Tennen Rishin-ryū Bujutsu hozonkai enbu2(Kumi-uchi)

why is modern Kendō so different from the swordsmanship of the past?

So, a natural question arises: why is modern Kendō so different from the swordsmanship of the past? The general answer for all martial arts, not just Kendō, is that the decline of the samurai class and the influence of the Meiji era’s civilization and enlightenment led to the decline of traditional combative arts. However, gekiken’s public events organized by prominent figures such a Sakakibara Kenkichi (1830-1894), the establishment of a gekiken section within the Tōkyō Metropolitan Police Department’s and the preservation work carried on by the Dai Nippon Butokukai in the Meiji era, greatly contributed to maintain the swordsmanship practice almost unchanged from the Bakumatsu to the early Shōwa period. The significant turning point was the Pacific War.

After the defeat, Japan was occupied by the Allied forces, and the practice of Kendō was prohibited. Kendō was revived in Japan through the establishment of the All Japan Kendō Federation in 1952. However, post-war Kendō became a democratic sport, banning dangerous techniques such as joint locks, leg sweeps, and throws to make it accessible for people of all ages and genders, resulting in the development of modern Kendō.

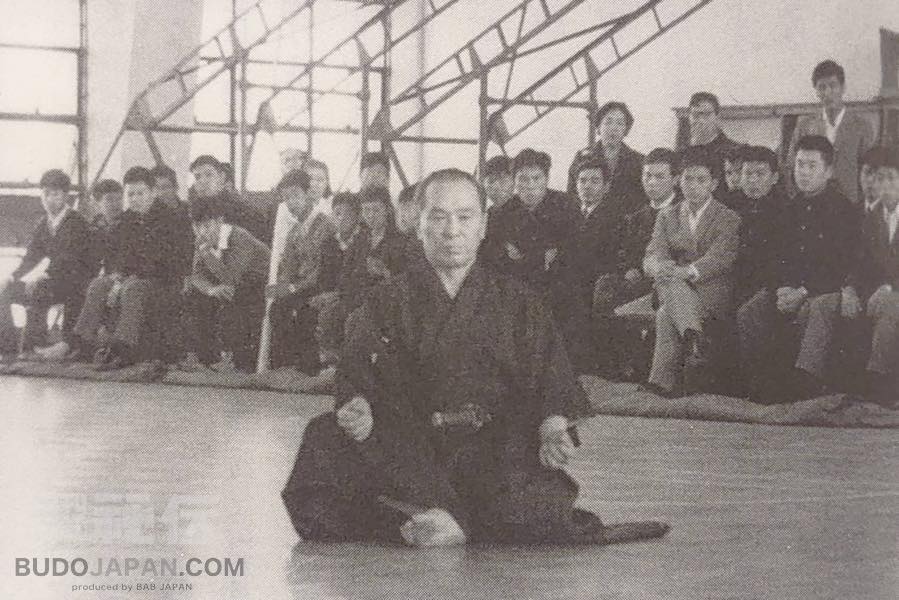

sword master Haga Jun’ichi

However, it does not mean that the pre-war Kendō has completely disappeared. The Haga dōjō, opened by the sword master Haga Jun’ichi (1908-1966) continues to practice Kendō as ‘a martial art’. I had the pleasure of visiting the Haga dōjō for training and received instruction in Iaidō and Kendō from the head teacher Uki Terukuni Sensei, direct student of Haga Sensei.

Haga Jun’ichi (1908-1966)

Uki Terukuni with Haga Sensei

Uki Terukuni Sensei

the Kendō practice at the Haga dōjō

Uki Sensei takes care of shinken (real sword)

At the Haga dōjō, the practice of Iaidō is conducted at the beginning of each training session for two reasons. First, unlike modern Kendō, the Haga dōjō does not have warm-up exercises, as all the body movement necessary in Kendō can be learned through Iaidō. The second reason is that Iaidō practice is done only with shinken (real sword). Iaitō are not allowed here. It goes without saying that the risk of injury during drawing and cutting exercises grows exponentially with a real sword when a student is physically and mentally exhausted after an intense Kendō practice.

the practice of Iaidō

The Iaidō schools transmitted at the Haga Dōjō are the Ōmori-ryū and the Hasegawa Eishin-ryū. I was taught the first and second forms of the Ōmori-ryū by their teachers. Luckily, there are similar basic forms in my school, so I was able to follow without struggling too much. After finishing the Iaidō practice, as everyone was about to put on protective gear, Uki Sensei’s advanced students performed a special demonstration of the Goka-gogyō forms of Shindō Munen-ryū as transmitted in the dōjō. After that, I also put my bōgu on.

The Iaidō schools transmitted at the Haga Dōjō are the Ōmori-ryū and the Hasegawa Eishin-ryū. I was taught the first and second forms of the Ōmori-ryū by their teachers. Luckily, there are similar basic forms in my school, so I was able to follow without struggling too much. After finishing the Iaidō practice, as everyone was about to put on protective gear, Uki Sensei’s advanced students performed a special demonstration of the Goka-gogyō forms of Shindō Munen-ryū as transmitted in the dōjō. After that, I also put my bōgu on.

the Goka-gogyō forms of Shindō Munen-ryū

kihongeiko(taiatari 1)

kihongeiko(taiatari 2)

kihongeiko(taiatari 3)

kihongeiko(Yokomen Uchi 1)

kihongeiko(Yokomen Uchi 2)

At this point, two significant differences from modern Kendō became apparent. The first is that basic training (called kihongeiko) is hardly conducted at the Haga dōjō, and one immediately engages in jigeiko (free sparring). The second is that, when striking at the opponent, they use an alternating footwork (ayumiashi) instead of a shuffle step (okuriashi). In modern Kendō, moving forward with an okuriashi and hitting the opponent just an instant before the right foot impact on the wooden floor is indeed the fastest and most efficient way to score a point (ippon). However, this is possible in a context where the bamboo sword is used. With a Japanese sword weighing over a kilogram, that kind of speed can’t be achieved with just a wrist snap without a proper furikaburi (swinging overhead movement). Students at the Haga dōjō are very conscious of this, swiftly changing from seigan stance (middle-level posture) to jōdan (upper posture) by advancing the left foot, and rapidly swinging down the sword with the right foot at the same time, targeting an opening in their opponent’s guard. In doing so, every strike generates a lot of power. As the training went on, I witnessed taiatari (body collisions), ashigarami (leg sweeps), nagewaza (throws), and osaekomiwaza (submission) in a perfect late Edo period training fashion. At that moment, I began to think about how to counter such style.

furikaburi (do uchi 1)

furikaburi (do uchi 2)

furikaburi (jodan uchi )

Despite being nervous, I approached each of the instructors one by one and trained with them. After several exchanges and takedown defenses (luckily jūjutsu plays a big role in Tennen Rishin-ryū as well), I gradually realized that I was being pushed back toward the wall with each strike I received. Every time I was struck on the men (head), kote (gauntlet), dō (body), and tsuki (thrust to the chest or throat), I pondered on the reason why the Shindō Munen-ryū, on which the Kendō practiced at the Haga dōjō is based, was referred as one of the strongest schools in Edo. Nevertheless, no matter how hard I was hit, how much pain I felt, I was determined not to give up and continued to face each person. It might sound like I am boasting, but the only reason I didn’t physically and mentally break until the end was because I had conditioned myself through Tennen Rishin-ryū’s strenuous practice during the past fifteen years.

jigeiko (free sparring) with Uki Sensei

jigeiko 2

jigeiko 3

jigeiko 4

jigeiko 5

After the practice ended, I took off the men and politely greeted all the teachers and students. Uki Sensei approached me and said with a smile, ‘There are not many people who want to train more after our practice is over’. I responded with another smile, saying ‘I understand the meaning of your words very well, Sensei’. With that, my experience of pre-war Kendō at the Haga dōjō came to an end. Despite being thoroughly beaten, I felt a great sense of accomplishment and fulfillment, and felt extremely grateful for the opportunity that I had been given. To become a better martial artist, I realized that there is no other way than to engage with much stronger swordsmen and their schools through continuous practice.

talk with Uki sensei after Keiko

The Kendō promoted by the All Japan Kendō Federation and the one carried on at the Haga dōjō are aiming in different directions, and I personally think there won’t be many interactions in the future.

Still, for those interested in traditional martial arts, especially the training methods of schools from the mid to late Edo period, I strongly recommend visiting the Haga dōjō at least once. Personally, I consider the activities of the Haga dōjō as a success story, and I hope that in the future there will be more events and gathering where swordsmen from various schools can interact through free-sparring practice. If that happens, a new era may come where friendly matches between schools can help revitalize arts that are inexorably disappearing. For a practitioner like me, working towards obtaining a full mastery license (Menkyo) in Tennen Rishin-ryū under the guidance of my teacher Katō Kyōji, that would be something extremely beneficial.

References:

– Bakumatsu Kantō Kenjutsu Eimeiroku no Kenkyū (Research on famous swordsmen record from Bakumatsu in the Kantō area – Watanabe Ichirō)

– Iyo Shidankai Bunkozō ‘Gekiken Shiai Oboechō’ (Chronicles of free-sparring matches preserved in the Iyo Historical Society – Edited by Enomoto Shōji)

– Bakumatsu Kenkyaku Hiroku – Edo Machidōjō no Ken to Hito (Chronicles of swordsmen from Bakumatsu – the sword and men of the dōjō in Edo – Watanabe Makoto)

– Shiryō Kindai Kendōshi (History of modern Kendō – Nakamura Tamio)

– Kikoku Kendōshi (History of Japanese Kendō – Ozawa Aijirō)

– Kendō Shinan (Mastering Kendō – Ozawa Aijirō)