A Recommendation for Fieldwork! Notes from Karate History Research and Observations

Report & Text: Nomura Akihiko, Composition: Schultze-Nadoyama Sanae

Deepen Your Understanding of Karate by Studying History

Connecting Okinawa, Mainland Japan, and the World

Koyama Masashi – Karate Research Institute

Yannick Schultze – Researcher of Japanese Martial Arts History

Koyama Masashi has achieved numerous accomplishments as a member of the Japanese national team in both kumite and kata at karate tournaments in Japan and abroad. As a pioneer in the study of Gōjū-ryū and Naha-te, he has also paved the way for the next generation.

This time, at the request of German researcher of Japanese Budō history Yannick Schultze, a special dialogue on the “Historical Study of Karate-dō” with Mr. Koyama was conducted during Schultze’s research visit to Japan this year!

Website of Koyama Masashi: https://koyamakaratedokenkyuukai2023.jimdofree.com/

Website of Yannick Schultze: www.karate-kenkyu.com

Interview Preface

Visiting a Pioneer in Karate History Research!

Yannick Schultze, who has presented valuable research findings in this magazine’s irregular series “Exploring Okinawan Karate History!”, is a German-born historian. As a teenager, he was deeply inspired by action films featuring Bruce Lee and Jet Li, which sparked his admiration for East Asian martial arts. He recalls that as Okinawan kobudō—founded by Matayoshi Shinpo—began to spread into Europe, he found an opportunity to study traditional Okinawan martial arts.

Motivated by a strong desire to learn traditional martial arts at their source, he visited Okinawa in 2008. There, he deepened his research into traditional karate and Okinawan kobudō. Today, he continues to train in Tō’on-ryū Karate-dō and Matayoshi Kobudō while advancing his historical studies.

On the other hand, his wife, Sanae Schultze-Nadoyama, was told by her grandfather that Naha-te karateka, Higaonna Kanryō, was among their ancestors. This revelation prompted her to obtain the family registry and other genealogical records. While conducting field research into karate history, she encountered difficulties, as many documents had been lost in the ravages of war.

The couple continues to pursue their investigation into Higaonna Kanryō based on existing sources. In tracing the legacy through Higaonna’s prominent disciples—such as Miyagi Chōjun and Kyoda Jūhatsu—they came across a serialized article by Koyama Masashi titled “My Miyagi Chōjun” (Waga Miyagi Chōjun), published in the 1980 issue of Gekkan Karate-dō magazine.

As Yannick primarily belonged to the European karate community, he had few direct connections with Japanese karate practitioners. However, by following various leads and receiving support from many people, he was finally able to get in touch with Koyama.

In 2022, during a field research visit to Japan, the couple realized their long-cherished wish and met Koyama in Ōsaka. They exchanged research findings, marking a significant milestone in their scholarly journey. It was also Koyama who provided the opportunity for Yannick to present his work in this magazine.

In response to Yannick’s request, Koyama has now shared with us the story of his karate journey and insights into his research.

The Seeds of Karate History Research Planted in Kagawa

Yannick

Koyama sensei, I feel very humbled addressing such a great teacher, but may I ask you to please introduce yourself, and tell us how you first encountered karate, as well as what led you to begin your research into the history of Karate-dō?

Koyama

I grew up in Ōsaka until the third grade of elementary school, then spent nine years—from that point until graduating high school—in Toyohama Town, Kagawa Prefecture (present-day Kanonji City), where my parents were originally from. After that, I returned to the Kansai region. Although I only lived in Kagawa for nine years, I think it was a good thing that I spent that formative period—when you really start to feel and think about things—not in the city, but in the countryside.

My father practiced jūdō. He was born in Taishō 12 (1923) and worked as a teacher after the war, but he was quite wild and mischievous (laughs). When he got drunk, he’d get into fights. But no matter how many times he threw someone with jūdō, they would get back up, so he thought, “Maybe I need to learn karate too,” and that’s how he started. I’ve heard he began practicing karate after moving to Ōsaka, and it was a style connected to Uechi-ryū. Around 1968, he built a dōjō on our family property and started teaching both jūdō and karate.

At the time, I was playing baseball from elementary school all the way through my senior year of high school. But after we lost in the final summer tournament of my last year, I thought, “Well, maybe I’ll try karate,” and so I practiced for about six months until I graduated.

Back then in Shikoku, when people said “budō,” what came to mind was Shōrinji Kenpō, which had its main headquarters in Tadotsu. There weren’t any high schools with karate clubs—none at all. That was the kind of era it was. Then one day, Kasao Kyōji (a graduate of Waseda University’s karate club and a researcher of Chinese martial arts) came to my father’s dōjō. He demonstrated various kata for us and even taught me the Heian series from Shodan to Godan. Kasao himself was a truly fascinating person—he shared stories like something out of a travelogue, about his journeys around the world and his time in Okinawa. That kind of experience formed the foundation of my karate research. It was also Kasao who said to me, “You should go to Okinawa while you still can.”

There was also a senior from Ritsumeikan University named Kimura Zōnosuke, who was from Takamatsu and worked as a journalist for the Yomiuri Shinbun. He wrote about karate history in the Gōjūkai’s official magazine, and his work had a major influence on me as well. All of these experiences are connected to what I’m doing now—but back then, I had no idea they would lead me here.

The Karate Club of Ritsumeikan University and the Spread of Gōjū-ryū

Yannick

There are some very fascinating aspects in the story about your father. In postwar Germany, many people followed a similar path. Jürgen Seydel, considered a pioneer of karate in Germany, originally trained in jūdō and only later encountered karate for the first time in France. Many of the karate instructors and pioneers who became active in Germany also came from backgrounds in jūdō or jiu-jitsu.

In that context, may I also ask about your own alma mater, the Ritsumeikan University Karate Club? Ritsumeikan University is said to have been the first institution of higher education on the Japanese mainland where Miyagi Chōjun sensei personally taught. What significance did that early relationship with Miyagi sensei hold in terms of the spread of Gōjū-ryū on the mainland?

Koyama

At the Ritsumeikan University Karate Club, there was a man named Yogi Jitsuei, a student of Miyagi Chōjun sensei. Yogi senpai was born in 1912 (Taishō 1), and by the time Miyagi sensei began using the name Gōjū-ryū around 1931 (Shōwa 6), Yogi was already his student. He enrolled at Ritsumeikan University in 1934 (Shōwa 9).

At that time, Miyagi sensei was in Hawaiʻi, but after returning to Japan, he performed a demonstration together with Yogi senpai at the [Kyōto] Butokuden. According to Yogi senpai, they demonstrated Sanchin and Seisan, and Miyagi sensei especially liked Seisan.

A rare photograph featuring all the prominent figures of mainland karate at the time. From left (honorifics omitted): Nakayama Masatoshi (Chief Instructor of the Japan Karate Association), Yamaguchi Gōgen (President of the All Japan Karate-dō Gōjū-kai), Ujita Shōzō (President of the All Japan Karate-dō Federation Gōjū-kai [Public Interest Incorporated Foundation]), Okamura Mitsuyasu, Yogi Jitsuei, and although only half his face is visible, Kisaki Tomoharu (former Chairman of the All Japan University Karate-dō Federation).

There was another senior, Yamaguchi Gōgen senpai, who had witnessed Miyagi sensei’s very first seminar on the mainland, which took place at Kyōto University in 1928 (Shōwa 3). In any case, it was certainly Yogi senpai who served as the connection between Ritsumeikan and Miyagi sensei. There’s a record of a karate club already existing at Ritsumeikan by 1935 (Shōwa 10), so this is considered the founding year of the Ritsumeikan University Karate Club.

Ritsumeikan was the first university where Miyagi sensei taught, and after the war, it was the Ritsumeikan University Karate Club that spread Gōjū-ryū on the Japanese mainland. Also, Yamaguchi Gōgen senpai participated in the founding of the Japan Karate Federation (JKF), so I believe that it is thanks to him that Gōjū-ryū 剛柔流 became one of the four major styles recognized by the federation—together with Shōtōkan-ryū 松濤館流, Wadō-ryū 和道流, and Shitō-ryū 糸東流. In Okinawa, the three major styles are Uechi-ryū 上地流, Shōrin-ryū 小林流 (also written as Shōrinji-ryū/Shōrin-ryū 少林寺流/少林流 or Matsubayashi-ryū 松林流), and Gōjū-ryū. So Gōjū-ryū is the only style that became a major style both on the mainland and in Okinawa.

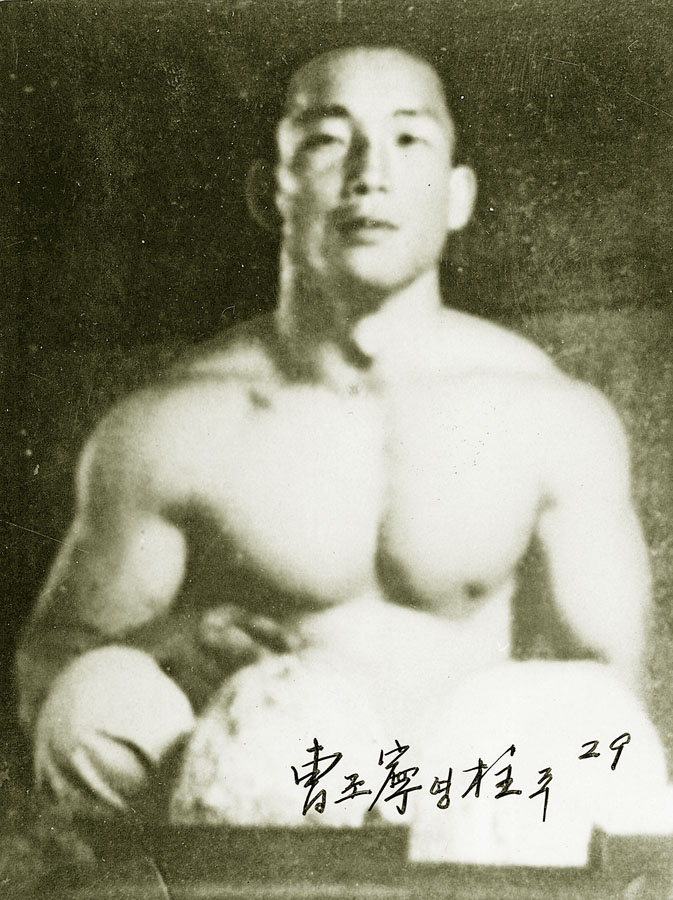

Sō Neichū, a junior of Yamaguchi Gōgen

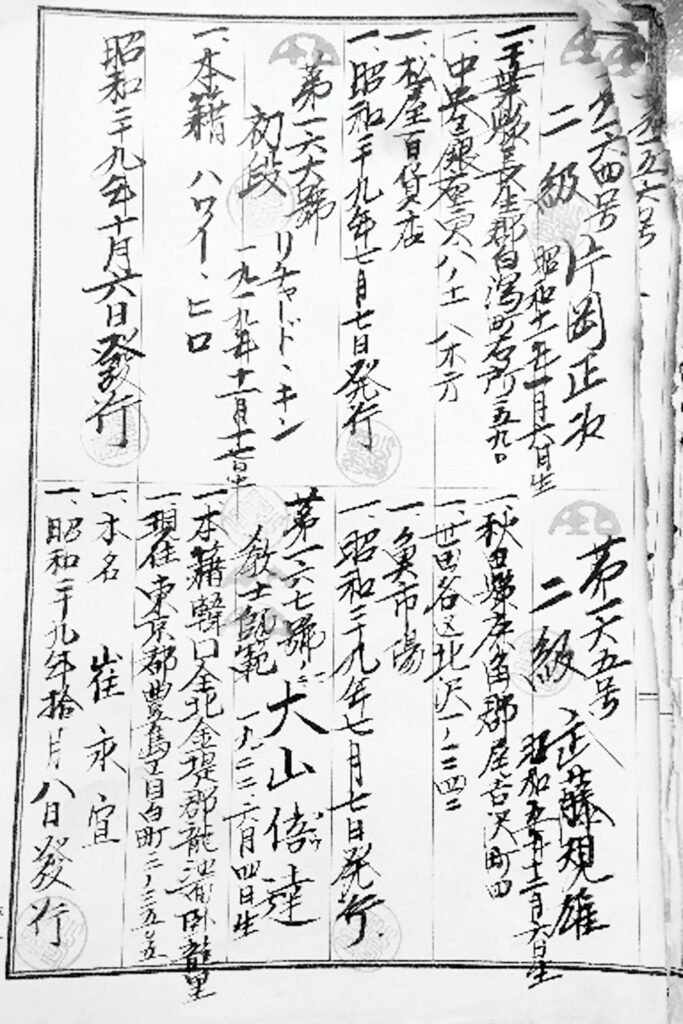

A name list from the time of the founding of the Gōjū-kai (photographed by Mr. Koyama from materials owned by Yamaguchi Gōshi) showing the name of Ōyama Masutatsu

Moreover, the Ritsumeikan Karate Club and the university itself had a strong connection with Ishiwara Kanji. Fukushima Seizaburō, a student of Ishiwara, founded the group called Gihōkai. Within that group was Sō Neichū senpai, a junior to Gōgen senpai, who served as the dormitory head of the Gihōkai Kyōwajuku (a student dormitory for people from across East Asia). He also taught Gōjū-ryū to Ōyama Masutatsu. Since Sō senpai originally had a background in boxing and weightlifting, that aspect contributed to Ōyama’s competitive style in the postwar period as well.

Kumite Training and Kata Competition in the Early to Mid-20th Century

Yannick

Fritz Nöpel, a pioneering figure in the German karate world, also became involved with the karate of Ritsumeikan University through a rather unusual route. In 1956, aiming to attend the Olympic Games held in Melbourne, Fritz Nöpel began a journey by bicycle from Germany to Asia, a trip that would take two years. During this journey, he stayed in Ōsaka for a while, where he met Kisaki Tomoharu sensei, an alumnus of Ritsumeikan University. Under Kisaki’s intensive instruction, he became the first person to transmit Gōjū-ryū to Europe. In this way, thanks to their achievements, one of the major karate styles was brought to Europe.

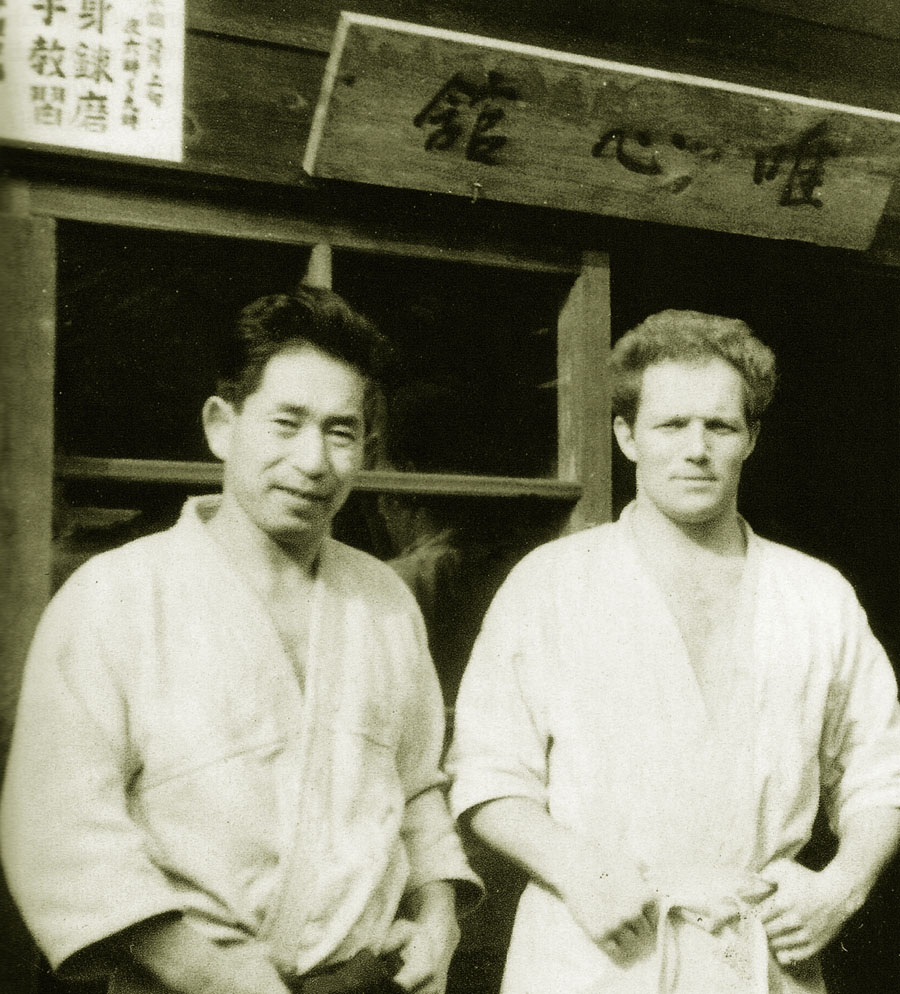

Left: Kisaki Tomoharu, Right: Fritz Nöpel

While Gōjū-ryū was expanding its influence, styles such as Shōtōkan-ryū, Wadō-ryū, and Shitō-ryū were spread across Europe by Japanese instructors who traveled there, and this was the general flow of karate’s dissemination throughout the continent.

Could you also tell us more about the training within university karate clubs, the introduction of kata competitions, and the evolution of organizational structures?

Koyama

The official adoption of kata competition occurred at the 4th World Karate Championship (1977, Tōkyō). When I was a student, the matches were only kumite (sparring). Training consisted of two hours of kihon (basics) followed by about thirty minutes of kumite. In those days, bleeding during kumite was common. Kata was learned mainly during training camps and was required for promotion tests. Because I had the image of Kasao in my mind, I liked kata too, but I think the time spent practicing kata back then was quite short.

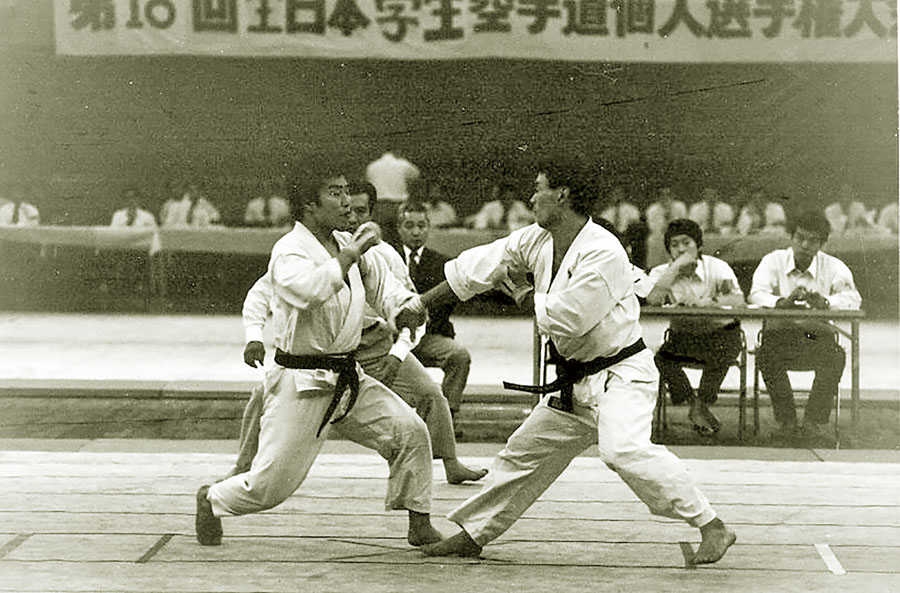

During his time at Ritsumeikan University, Mr. Koyama (left) in a valiant pose at the 18th All Japan University Karate Championship Individual Kumite match.

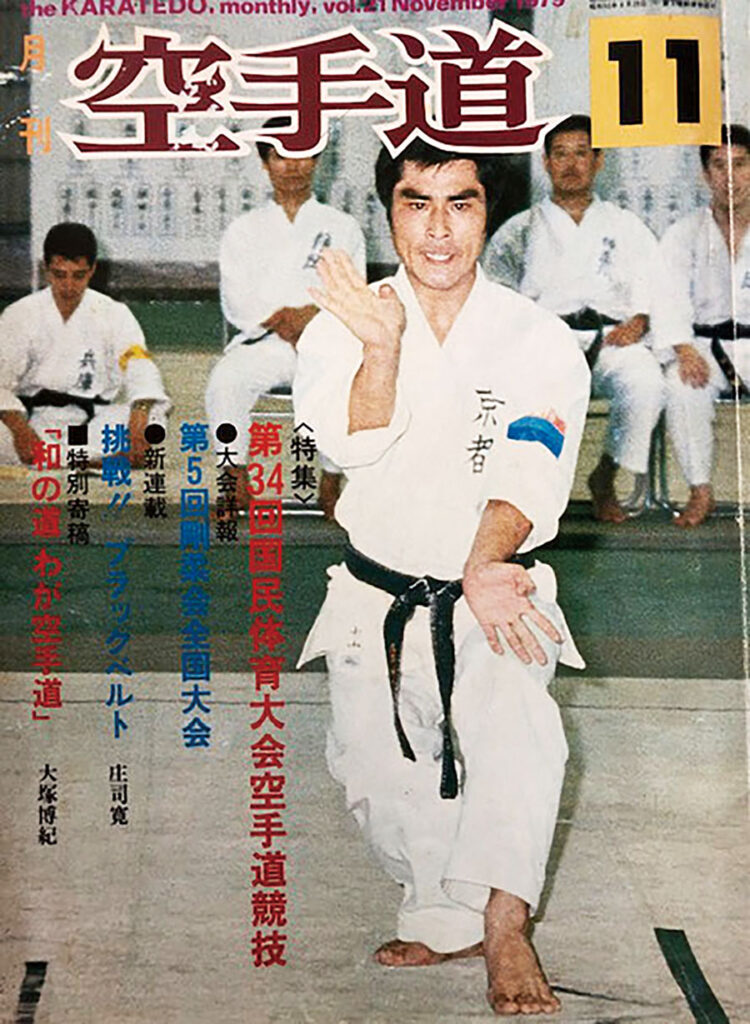

Mr. Koyama’s kata performance at the 34th National Sports Festival, which appeared on the cover of “Gekkan Karate-dō”.

At that time, free kumite included throws, and while strikes to the eyes and throat were not allowed, attacks to vital points were attempted by grabbing. No gloves were worn. Within that context, how to protect oneself, counterattack, and psychologically break the opponent’s fighting spirit was very important. In the beginning, various accidents happened. Those without technique couldn’t control themselves well, so it was dangerous. That led to the creation of rules. Around the 1950s (Shōwa 30s), such discussions arose, and rules were formed within the student federation. Ōyama called it “dance karate,” but in organizational terms, the student federation, the Japan Karate Federation (Zenkūren), and the WKF, were beginning to build proper structure, norms, and rules that would later lead to the recognition by the IOC and eventual inclusion in the Olympics.

The acquaintance between Miyazato Ei’ichi of Jundōkan and Kojō Yasuko

Yannick

During the 20th century, especially in its first half, the way karate spread and changed—and how kumite (sparring) became a central element within that evolution—is a fascinating story. For example, within Okinawa Prefecture, Chibana Chōshin is said to have mainly taught kata and did not place much emphasis on kumite training.

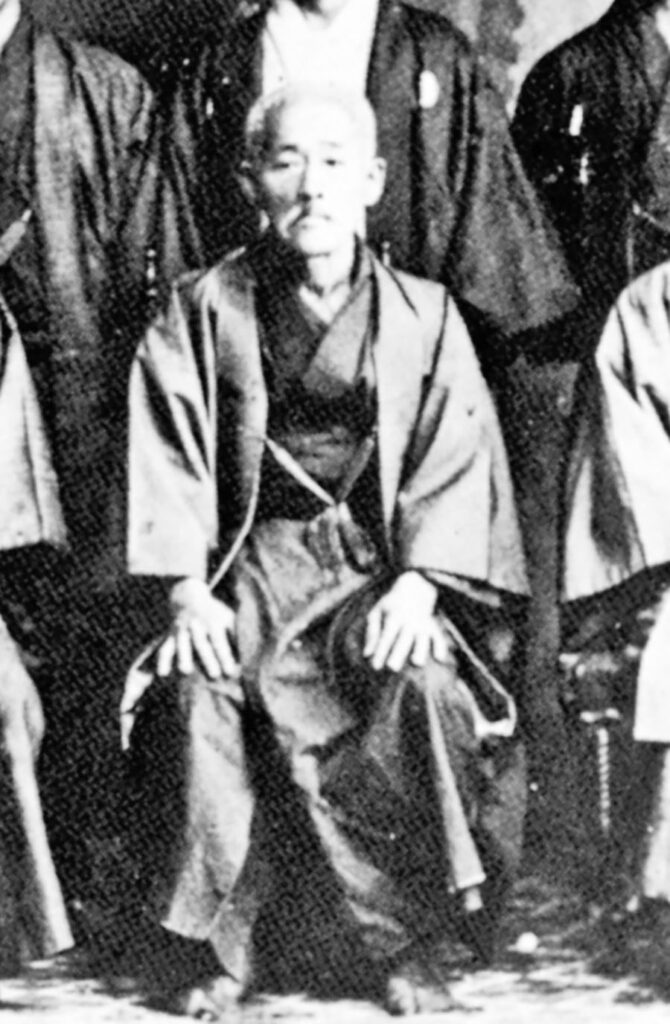

Yabu Kentsū (1866–1937)

Hanashiro Chōmo (1869–1945)

Chibana Chōshin (1885–1969)

In contrast, Hanashiro Chōmo and Yabu Kentsū are described as supporting kumite, with Yabu known to have conducted kumite training using protective gear as early as 1929. This was arguably a pioneering step that foreshadowed the later development of sport karate.

Next, I would like to hear about your own field research and studies in Okinawa, especially your encounters with the family of Miyagi Chōjun.

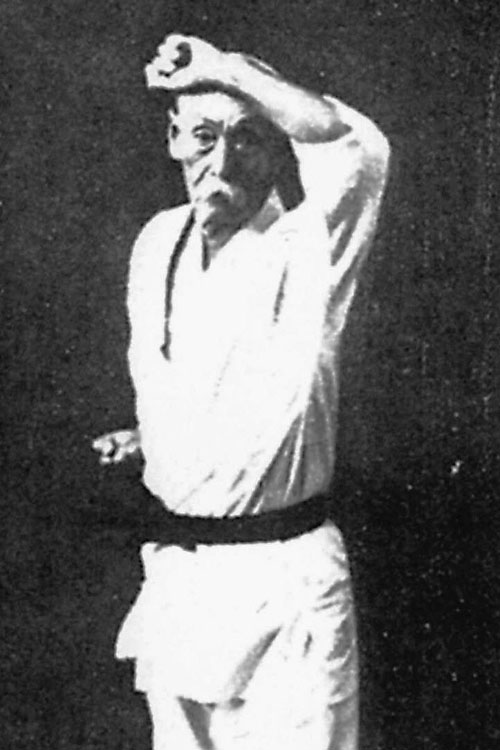

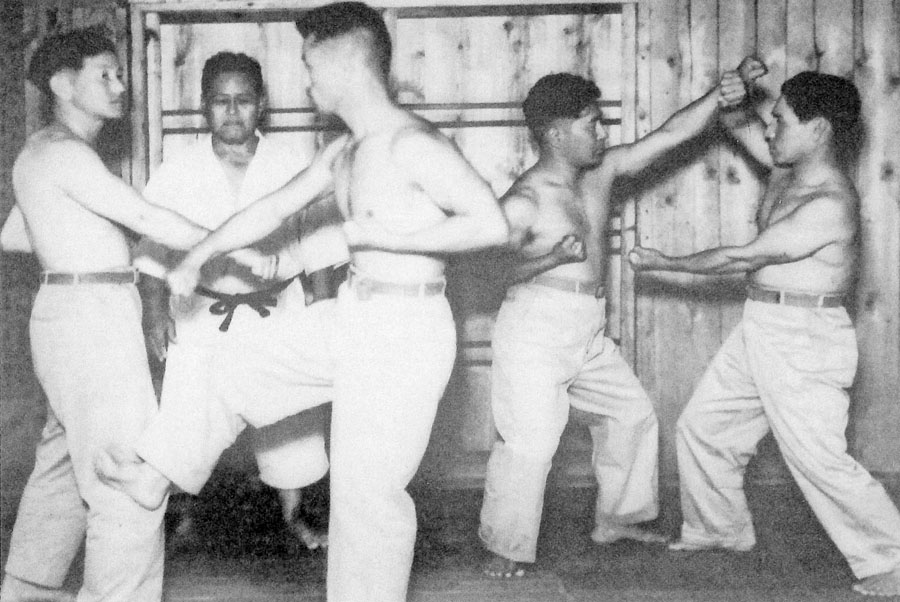

Training scene around 1952 led by Miyagi Chōjun (back left)

Koyama

When I was in high school, I had heard stories from Kasao and had wanted to visit Okinawa at least once. So, after becoming champion in my fourth year at university, I went with two fellow classmates to the Jundōkan in Naha. There, we were asked to demonstrate our kumite, and I think the speed of our techniques was quite fast. At that time in Okinawa, competitive kumite experience was limited, so I believe they couldn’t quite keep up with our speed.

Back then, the Jundōkan had five or six makiwara lined up, with chiishi (stone weights with handles) and sashi (stone locks) around. Everyone would come to the dōjō after work and practice individually before going home. The training method in Okinawa at that time was completely different from the training at university karate clubs. I think it was the same way before the war as well. It was a training environment developed under those conditions and was different from competitive karate.

Because of this Okinawan experience, when I joined the Physical Education History Research Department at Kyōto University of Education, I decided to make Miyagi Chōjun sensei the theme of my research. I sent a letter with about twenty questions to Miyazato Ei’ichi of the Jundōkan. In response, he invited me to come visit. Miyazato introduced me to Chōjun sensei’s family, and through that connection, I was able to hear stories from many disciples and related people, and from there it expanded further.

During an Okinawa research and interview trip: Ms. Kojō Yasuko on the left, and Mr. Koyama on the right.

The best experience was being able to hear directly Chōjun sensei’s daughter, Kojō Yasuko, and his fourth son, Ken. I learned that in 1927, Kanō Jigorō had visited Okinawa and was hosted by Miyagi Chōjun and Mabuni Kenwa. Chōjun sensei had sons named Takashi (Kei), Kin, Jun, and Ken. Jun died in the Tekketsu Kinrōtai (Student Units of Blood and Iron for Emperor), but his name was given by Kanō Jigorō. They told me that Jun carried a spear given to him by his father until his death — he never let go of it.

I also called Takashi, but he seemed cautious and was unwilling to talk. Takashi apparently entered the Busen (Budō Senmon Gakkō – Martial Arts Specialized School) in 1933. Around that time, Chōjun sensei began making frequent trips to Kyōto, and in 1934, Yogi entered university.

That is how the connection with Ritsumeikan University was formed. According to Kojō Yasuko, Chōjun sensei went to teach there almost every year.

The Dai Nippon Butokukai and Karate (Kūshu)

Yannick

According to “My Miyagi Chōjun,” you visited Okinawa in 1977. I first visited Okinawa myself in 2008, and compared to that time, the island has changed dramatically. I still clearly remember when I arrived. The humidity typical of the subtropical region was intense the moment I got off the plane. Also, the international terminal at that time was much smaller compared to the current one.

Koyama sensei, with the support of Miyazato Ei‘ichi and others, you built valuable connections within Okinawa Prefecture, which had a significant influence on your research there. By the way, you also conducted in-depth research into Miyagi Chōjun’s relationship with the Dai Nippon Butokukai.

Could you please explain once again what role he played within the Dai Nippon Butokukai?

Koyama

Karate officially joined the Dai Nippon Butokukai in 1933 (Shōwa 8). That same year, a branch was established in Okinawa Prefecture, and the following year, Miyagi Chōjun sensei became a regular council member, marking the beginning of significant developments.

By 1935 (Shōwa 10), Ueshima Sannosuke performed a demonstration at the Butokuden together with his daughter, and Miyagi sensei performed a demonstration accompanied by his senior student Yogi Jitsuei, who was studying at Ritsumeikan University. Karate-related activities became increasingly common.

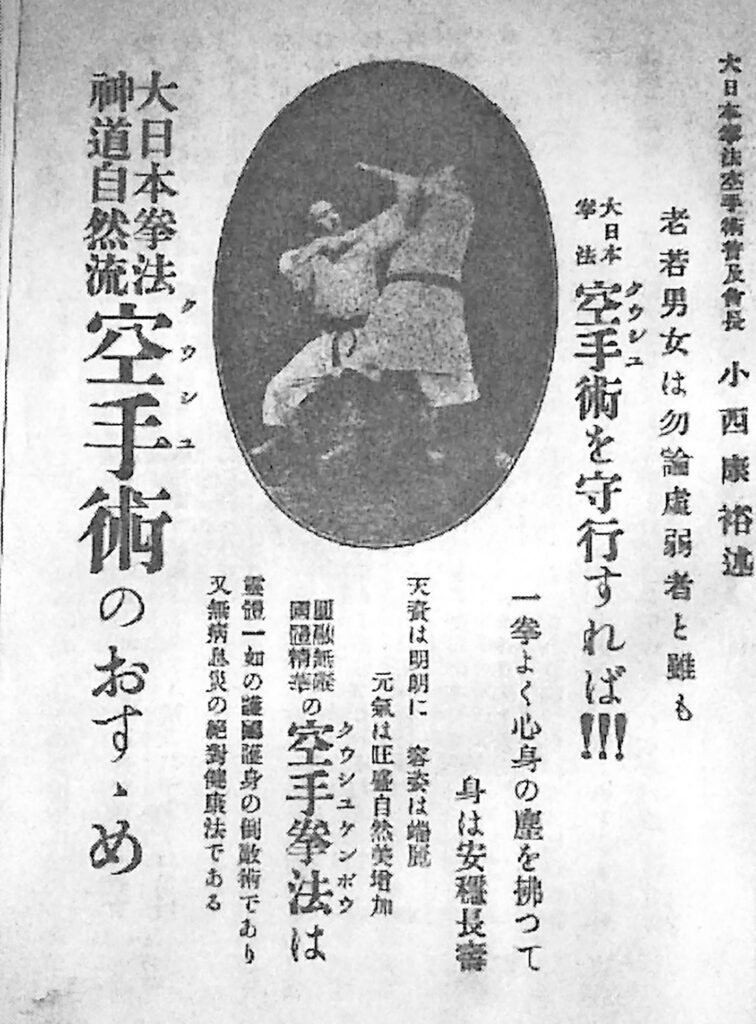

Then, in 1937 (Shōwa 12), karate, which had previously been classified as a branch of jūdō within the Dai Nippon Butokukai, was officially recognized as a “martial art certified by the Butokukai.” At that time, Konishi Yasuhirō, Ueshima Sannosuke, and Miyagi Chōjun were each awarded the title of “Kyōshi” in “Karate-jutsu”. After this, the number of candidates for the rank of “Renshi” gradually increased.

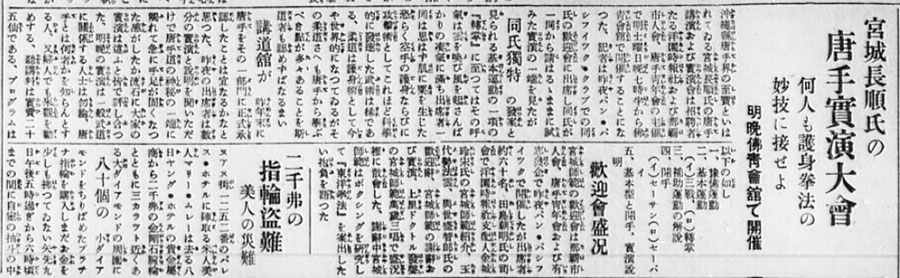

Konishi Yasuhirō came from Takenouchi-ryū jūjutsu, and Ueshima Sannosuke from Kushin-ryū jūjutsu. In the demonstration program of the 33rd Butoku Festival in 1929 (Shōwa 4), Miyagi sensei was listed as performing “Karate-dō” (唐手道) and Konishi Yasuhiro as performing “Nihon Kenpō Karatesujutsu” (日本拳法空手術). However, we should note that at this stage, it was still pronounced “kūshu” (くうしゅ) and not “karate.”

From the investigative article “Tracing Miyagi Chōjun’s Visit to Hawaii” by Yannick, published in the February 2025 issue of this magazine.

The Hawaii Hōchi (May 11, 1934 edition), which reported on the karate demonstration event held by Chōjun Miyagi in Hawaii, describes it as “…the self-defense and offensive techniques of Karate (Kūshu)…” Furthermore, among the listed demonstration items, “Tenshō” is already mentioned.

A promotional text by Konishi Yasuhiro, with the reading “Kūshu” given in furigana (phonetic guide). (Source: Karate-dō: Its History and Practice, p. 195)

The shift from using the term “Karate – Chinese Hand” (唐手) to “Karate – Empty Hand” (空手) began in 1930 (Shōwa 5) with Funakoshi Gichin sensei, and I believe the trigger for this change was the Keiō University Karate Club.

The Period of Development of Tenshō and Hypotheses Regarding Travel to China

Yannick

In recent years, I have personally sensed a growing interest in karate history even in Europe and America. Over the past 40 years, historians both on the mainland and in Okinawa have been collecting and researching columns written by renowned karate masters as well as the notes they took. Since the 2000s, many of these have been actively translated by foreign karate practitioners.

A longtime colleague of mine, Henning Wittwer, has been translating karate articles since 2007. The articles he has translated—such as Okinawa no Bugi and Karate no Hanashi are indispensable for those of us whose native language is not Japanese to deeply understand the historical development of karate. However, faithful translations like his are rare; unfortunately, many translations have been heavily altered from the originals or have had personal interpretations added, which is quite disappointing.

Besides your serialized article “My Miyagi Chōjun, ” Koyama sensei, you also published an article on Higaonna Kanryō in Gekkan Karate-dō in 1983. In your research on the lives and achievements of Miyagi Chōjun and Higaonna Kanryō, what aspects do you consider particularly important?

Koyama

First of all, regarding Okinawa Den Bubishi, it is unknown where Miyagi Chōjun obtained it. However, it does contain wording that became the origin of the name Gōjū-ryū, so its influence was certainly significant. That said, the “Rokkishu” mentioned there and “Tenshō” are not exactly the same thing.

Miyagi sensei had a nephew, I believe, named Tamaki Yūsei, and I heard from him about the yobi undō (warm-up exercise) and the time when Tenshō was developed. Tenshō was introduced around Taishō 10 (1921) with the words, “From today, we will do this.” Since there are no surviving records, this cannot be confirmed, but that is what was clearly said. If Tenshō was devised around Taishō 10, then since Higaonna Kanryō died in Taishō 4 (1915), it makes the most sense to think that from that time Miyagi sensei constructed it himself, creating yobi undō and building Tenshō as a kihon kata that connects not only to Sanchin but also to open-hand techniques (kaishu-gata).

Regarding the time of Higaonna Kanryō’s travels, we can only speculate. It’s not necessarily the case that he went solely for karate training. At the time, relations between Japan and Ryūkyū, as well as between Ryūkyū and Qing China, were unstable. Considering that he crossed the sea multiple times, many factors should be taken into account. At times, attacks by maritime pirates (kaikō) were possible. But the actual details are unknown, so we can only offer conjecture.

Miyagi sensei’s wife reportedly said that when she woke him in the morning or opened the door, his reaction was frightening. The only one who could have trained him like that would be Higaonna Kanryō. It is also possible that Higaonna had experienced even fiercer combat on his way by ship to Qing China. This kind of speculation comes from Miyagi sensei’s wife’s stories, but that is as far as it goes.

I think the “three-year theory” for Higaonna’s stay is unreasonable. There is a technique involving pulling up the testicles into the body, which I do every morning, but it’s difficult — even Miyagi sensei said he could do it only 3 times out of 10 attempts. Whether this technique has martial significance is another matter, but even mastering a single technique requires considerable training and time.

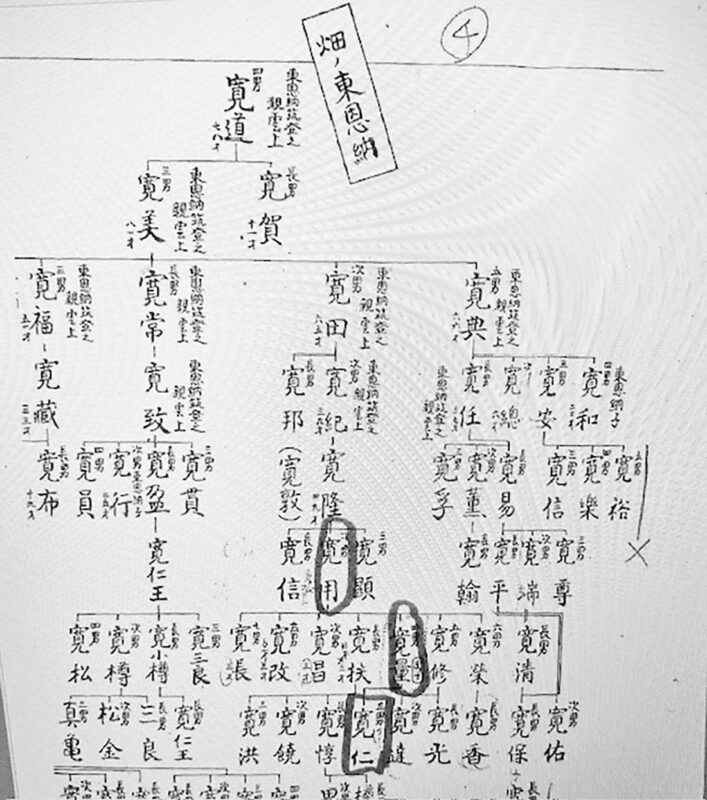

A valuable document titled “Shinsei Kafu” (Genealogy of the Shin family), detailing the family history of Higaonna Kanryō (東恩納寛量), presented to Mr. Koyama by Higaonna Kanryō (東恩納寛良)

There are records of Higaonna going to Fujian and returning to Okinawa. When calculated, the stay was three years. Based on this, Tokashiki Iken of Gōhakukai proposed the theory that Higaonna was in Fujian only three years. However, I think three years is impossible, and he probably made multiple trips back and forth. Around 2000, I presented papers titled “Doubts on the Theory that Higaonna Kanryō‘s Teacher was Whooping Crane Master Xiè Zōngxiáng” and “Higaonna Kanryō‘s Family Lineage” in the Karate-dō Kenkyū journal of the Japan Budō Society’s Karate Division, and I hope readers of Hiden will revisit these.

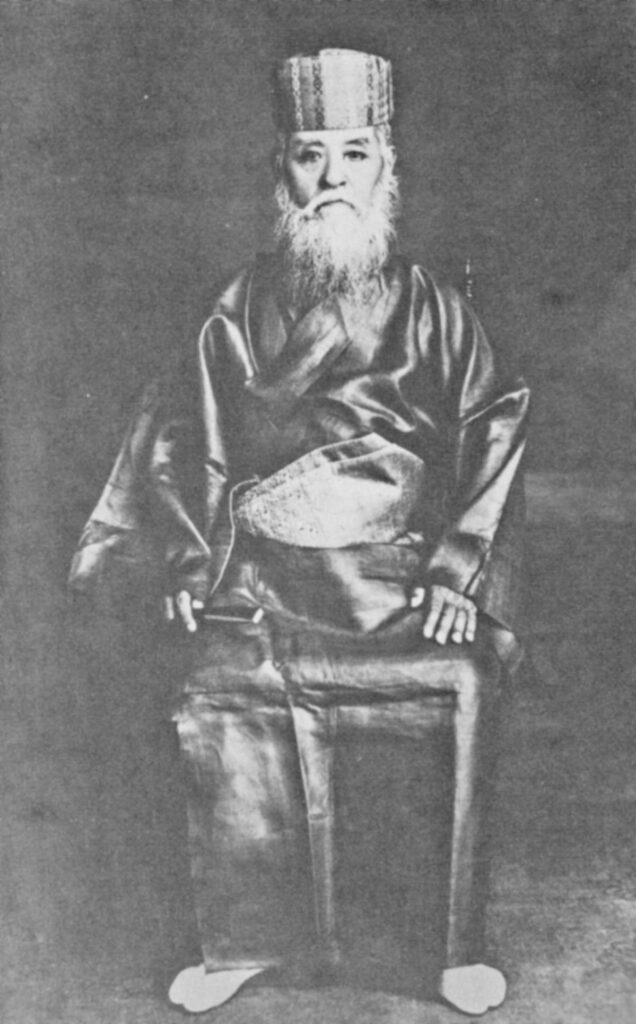

Higaonna Kanryō (1853–1915)

His student, Yoshimura Chōgi (1866–1945)

At that time, Okinawa was divided and in conflict between the pro-Japan faction and the pro-Qing faction. Higaonna was clearly part of the Qing faction, aligned with Yoshimura Chōgi (Ryūkyū royal family, 4th head of the Yoshimura Udun). Although there are no surviving records, I believe he probably traveled back and forth several times in this context. Of course, since no historical documents prove this, it is only speculation. Researchers can make conjectures about such matters but must not present them as definitive conclusions.

Yannick

Thank you for the fascinating episode regarding Tenshō. The account from Tamaki Yūsei was extremely valuable. In a passage from “Kōbō Kenpō – Karatedō Nyūmon”, co-authored by Mabuni Kenwa and Nakasone Genwa, the two mention that Tenshō was developed by Miyagi Chōjun, but as you pointed out, there is no clear description regarding the time of its development.

When it comes to the journeys of Higaonna Kanryō and Miyagi Chōjun to China, it is very important to consider them in light of their respective historical contexts. Higaonna Kanryō traveled to Fuzhou as a refugee or exile, and as you have mentioned, he may have had connections with Qing dynasty loyalist factions. On the other hand, Miyagi Chōjun visited Fuzhou at a time when Japanese imperialism was at its peak. By that time, Japan had already won the First Sino-Japanese War and the Russo-Japanese War—wars in which well-known karate practitioners such as Yabu Kentsū and Hanashiro Chōmo had actively participated. Furthermore, Japan had occupied Qingdao (formerly a German territory), which faces the Yellow Sea. It was during such a period of heightened political tension that Miyagi set foot on Chinese soil. Given these circumstances, I imagine it would have been difficult for him to ignore the anti-Japanese sentiments and engage in contact or form close exchanges with Chinese martial arts instructors.

As for the theory that Higaonna Kanryō’s stay in Fuzhou was short, I find it partially convincing. The theory proposed by Tokashiki Iken—that his stay lasted no more than three years—or the idea you pointed out, that he made several short visits rather than one continuous long-term stay, seem more plausible. Supporting reasons include the birth dates of Higaonna’s children and the tax revenue system of that time. Therefore, I have doubts about the theory that he was away from Okinawa for over ten years.

In closing, I would like to translate and introduce to a wider audience the “My Miyagi Chōjun series” written by you, which also served to connect us in the first place. For people like us, your on-site investigative records will serve as a great source of inspiration for non-Japanese karate practitioners. Thank you very much for today.

Mr. Koyama, who once conducted an interview in Okinawa with Iraha Chōkō, a disciple of Kyoda Jūhatsu. The photo shows Iraha in a Sanseru stance.

Yannick, currently studying Tōon-ryū under Ikeda Shigehide sensei (4th Sōke) in Ōita, performing Sanseru.

During the interview, Mr. Koyama personally saw and remembered differences in Iraha sensei’s Sanseru (such as the yama-tsuki and kansetsu-geri), and in the recent discussion, he exchanged views and demonstrated these differences together with Yannick!