Immersion in the ways of Okinawan power: visit to Zenpo Shimabukuro’s Dōjō

My interest for karate

My name is Pierre Sevaistre, and I’ve been practising Shōrin-ryū in Paris for the last fifteen years. My involvement in karate naturally made me want to move to the land of the Rising Sun, so I left Paris for Tokyo for a year. With the aim of respecting the heritage of my style, I kept the Shōrin-ryū approach and discovered a Seibukan club in Fuchū. There I’ve met my sensei Brian Arthur, head of the Tōkyō Fuchū Branch Dōjō. He invited me to train in Shimabukuro sensei’s Dōjō in Okinawa, as to return to the source of my style.

Seibukan club in Fuchū.

What is Shōrin-Ryū ?

Of the three founding styles of Okinawan karate, Naha-te, Tomari-te and Shuri-Te, Matsumura Sokon, a practitioner of the latter, was the primary influence on what became Shōrin-ryū少林流 and 小林流 (school of the little forest, pronounced after Shaolin). Ti (or Te in Japanese pronunciation) refers to the indigenous martial arts of the Ryūkyū kingdom.

Matsumura Sōkon had a disciple named Kyan Chōtoku (1870-1945), introduced by his father, Kyan Chōfu. When the Ryūkyū kingdom was abolished with the advent of the Meiji era, Matsumura Sōkon retired to the Shikinaen (Palace Garden). he trained the young Chōtoku among the well-known masters Asato Ankō, Itosu Ankō and Funakoshi Gichin.

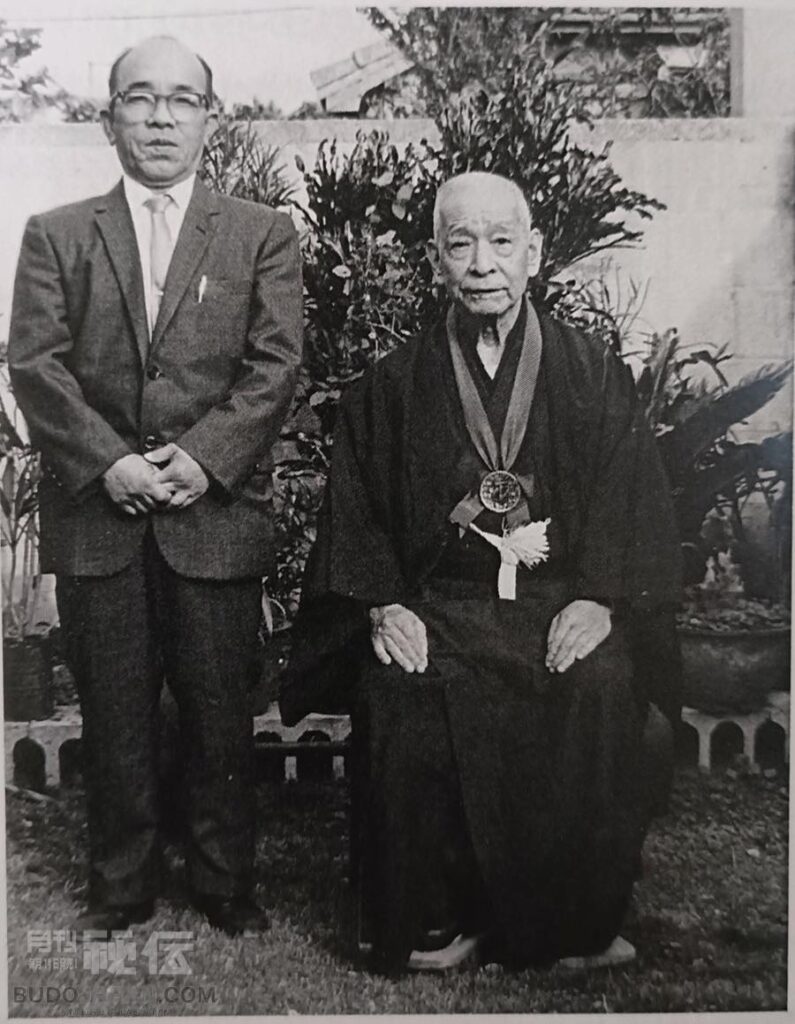

On the left in the photo is Kyan Chōtoku (1870-1945).

Respecting the characteristics of Okinawan karate, Shōrin-ryū is a karate that tend to be raw, efficient and devoid of aesthetics. A phrase that sums up this idea is “ichigeki hissatsu”(一撃必殺) , “death in one blow”, coined at a time when Okinawans had to be constantly prepared for enemy invasion, as the archipelago lay between the Chinese and Japanese kingdoms. This is somewhat different from today’s karate, where the stakes of “win or lose” have taken on greater importance, as opposed to those of survival and self-defense.

Great feeling in front of the monument of Chōtoku Kyan Sensei “Chan Mi Guwa” in Kadena Town.

The lineage of Kyan’s Karate

Seibukan’s teaching is taken directly from that of Kyan Chōtoku. Although Matsumura Sōkon had several students, including Kyan Chōtoku and Itosu Ankō, Shōrin-ryū became fragmented at the same time as the students had different interpretations of karate. As a result, depending on the ryūha, kata and stances are different. The Tomarite and Shurite instilled in Chan Mi Guwa’s karate led to the creation of rotating movements, a solid anchoring to the ground, to the point of catching the ground with the toes in search of power.

Kyan’s slender body would have required him to avoid taking direct blows, so he devised a method of advancing at 45-degree angles in his katas. Kyan Sensei studied for two years under Matsumura Sōkon and then with teachers from the Tomari area. This port area, populated by those involved in fishing and shipping, undoubtedly had an influence on the power of the techniques.

Itosu Ankō’s Shōrin-ryū had passed on with Chibana Choshin (This is my ryūha in France), Kyan’s Shōrin-ryū was only transmitted by a few key disciples, including Shimabukuro Zenryō and Nakazato Jōen. Other sensei, like Shimabuku Tatsuo and Nagamine Shōshin also passed down certain kata from Kyan sensei.

In this picture, we can see on the left two different heritages of Shorin-ryu: Zenryo Shimabukuro on the left and his contemporary, Chibana Choshin on the right. Source taken from the book Shorin Ryu Seibukan : Kyan’s Karate, Shimabukuro and Smith, Coal Mountain Productions, 2012, 406p.

The Shimabukuro family, keepers of the Seibukan school

In the 1930’s, Chōtoku Kyan met Shimabukuro Zenryō (1909-1969), one of the few people to have benefited from his teaching in Kadena/Yomitan. He decided to teach Shōrin-ryū karate to his son Zenpo, born on October 11, 1943. Under their aegis, the Hombu Dōjō was created in Jagaru in 1962 as well as the Seibukan, a primary representative of Kyan Chotoku’s teaching for years to come. At that time, help was welcome from all quarters, and family members, friends, neighbors and American students all pitched in. Originally, the second floor was used to accommodate American soldiers wishing to train there off of the base, but in 1969 it was turned over to Zenpo’s family after renovation.

Shimabukuro Zenpo is the fourth of five siblings. Very recently he was working as a real estate developer and has now five children, three girls and two boys. Zenshun sensei, his eldest son, is currently teaching at both the Hombu Dōjō and the Ōzato Dōjō and who will next lead the Seibukan Dōjō. Shimabukuro sensei’s younger son, Zenei sensei, assists at the Hombu Dōjō as well as the Ōzato Dōjō.

Today, Seibukan has schools in twenty countries (such as Germany, USA, England, UAE, India, Canada..), with the aim of expanding and perpetuating Kyan’s karate heritage.

Seibukan logo

My arrival at the Dōjō

Planning to train at the Dōjō on the same day I arrived on December 18th 2023 in Okinawa, I was excited to discover an island with a special atmosphere imbued with centuries of martial practice. At that moment, I recalled my years of practice and faced the exciting idea of treading for the first time the parquet floor of a Dōjō historically representative of my style.

When I was told to bring a towel and plenty of water; a little dubious at first, I soon realized how perceptive the advice was, as the body was so much in demand. Mixed with the humidity of Okinawa and the adrenalin of an exotic experience, I sweated profusely. What also struck me was the fact of mixing children and adults in the same kihon and kata exercises. So I was surrounded by every possible generation connected by dedication to karate and everyone was giving their best effort to progress.

Tanren, or the notion of forging

It’s often said that practice makes perfect. This maxim is all the more true in the case of karate, insofar as you can only strengthen yourself through routine exercises. At Seibukan, the same series of physical exercises has been performed at every session for over 60 years. These are Kihon Renshū (基本練習 “basic exercises”) and Zenshin Kōtai ( 前進後退 “advancing and retreating”)

They consist of the execution of warming up techniques such as stretching, as well as striking and defensive motions present in kata, with the aim of assimilating their essence. The key to gaining speed, strength and precision lies in their daily application, with the aim of emulating the opponent’s presence as closely as possible. For example, the uke kōgeki (simultaneous receiving and attacking)…

The class has begun at the Osato Shibu Dōjō. As is customary, with practitioners working on their flexibility during the kihon renshu.

Among the seven precepts written by Shimabukuro Zenpo and referenced in the official Seibukan book, we can read one of these:

「空手の習得においては理屈より鍛錬が重要である。」

“In mastering Karate, training (or forging the body & mind) is more important than theory.”

So tanren (鍛錬) literally means tempering and forging. It is precisely the way in which the practitioner inculcates karate into his body that will give it the form and resistance wished for. I wondered why Seibukan never changed these exercises. In fact, it’s all about repeating the same movement over and over again, sanding it down until every unnecessary gesture is erased, even on the smallest scale. I once heard a story about how it took masters 50 years of practice to master tsuki, the most basic movement in karate.

Moreover, usually present in all Okinawan styles, the kotekitae 小手鍛えis no exception to the rule and remains a very good way to strengthen the body. Thus, the word is composed of the same kanji 鍛 preceded by forearm.

This is a version of the kotekitae, in which you confront your forearm with that of your opponent and push in turn, remaining as stable as possible and without taking momentum.

Corrections or adaptation ?

These series of exercises made me aware of my tachikata (立ち方 “stances”) shortcomings in relation to Seibukan. Kobayashi style Shōrin-ryū uses uki ashi dachi (floating foot stance), which has a longer stance and weight more evenly distributed between the front and rear feet. In Kyan-lineage Shōrin-ryū, the counterpart is neko ashi dachi (cat foot stance), which is shorter and 90-95% of the weight is distributed on the back foot. So when I did the Kyan’s ukidachi, I had a hard time at first.

Obviously, each style has its own interpretation of tachikata. Zenshun Sensei was for example able to adjust the angle of my legs in ukidachi, the direction of my yoko geri or the height of my uchi otoshi. These are things that seem so small but as the saying goes, the devil is in the details, and when I was demonstrating Fukyūgata Ichi, the first kata I learned, there was one thing that jumped out at Zenpo sensei, and that was that I wasn’t pivoting outside my back foot in reinoji dachi after sending a tsuki.

I was not really aware about hanmi半身, the position that allows the practitioner to show only half of his body so as not to reveal too much of himself and to anticipate future attacks. In this school, whether it’s a jōdan age uke, chūdan soto uke, or shutō uke, many techniques are performed slightly diagonally so as not to show the whole body to the opponent. It took me a few times to comprehend it.

In Seibukan, each attack or defense is facilitated by utilized twisting 捻り(hineri) motions. Before a technique, the hand is always turned in the opposite direction to achieve a spin effect on deployment.

The makiwara

In the same theme of physical strengthening, the use of makiwara is very specific to the Okinawan style and is not widely used in the West. It is said that you cannot reach your greatest potential simply by strengthening your muscles and bones; you have to use makiwara to build the greatest power for your attack. Matsumura Sōkon and Itosu Ankō were still using it at the age of eighty.

When I used it there for the first time, it wasn’t so much the hardness of the straw that surprised me, but the supple rigidity of the board. Practicing with it made me aware of the need not to move the hip back on impact after retroversion of the pelvis – a mistake apparently frequently made by karateka, which reduces the intensity of the blow. Mudanashi (無駄無し“without waste”) refers to all unnecessary movements that impede the effectiveness of the stroke, and preparing the next technique in the previous move.

One of the special features of Seibukan is the diagonal fist, which uses the index and middle knuckle to strike the target. It is said that in order to keep his fist stable when aiming at targets larger than himself, Kyan placed his fist diagonally.

Thank you Kawaguchi San for lending your arm for the shot!

The kata

The main explanation for the difference in katas between the Seibukan and my Shōrin-ryū school in France lies in the different backgrounds of Matsumura Sōkon’s students, Chōtoku Kyan and Itosu Ankō. In fact, my school in France is a Kobayashi-ryu Shōrin-ryū, a term used by Chibana Choshin, who was Itosu’s student. Seisan or Wansu kata were unknown to me until then. If we had Pinan and Naihanchi in common, it’s because Zenpo Sensei also studied kata with Nakama Chōzō (1899–1982), a pupil of Chibana Chōshin.

Of course, kata practice is an important part of Seibukan. In Okinawa, the sensei announces the name of the next kata after finishing the previous one. If the practitioner is unfamiliar with it, he or she is required to withdraw with an “arigatou gozaimashita”.

I had learned Itosu no passai, but Seibukan teaches Kyan sensei’s version, which is simply Passai. I noticed that different versions of the same kata had the enbusen (演武線 “pattern”) relatively in common, except for techniques such as sagurite.

While I learned separate versions of Kūsankū, Kūsankū dai and Kūsankū shō, Seibukan students practice in what feels to me it in its original form. The Shimabukuro family is also known for its explosive, uncluttered execution of Kūsankū. Indeed Brian Arthur told me this: “Kūsankū is a kata that is so difficult to perform at a high level from start to finish. It’s very athletic and quite long. So you have to dedicate yourself to consistent, hard training in order to maintain agile and powerful technique throughout the kata. After training in another style for 25 years, I saw Shimabukuro Zenpo sensei’s Kūsankū. To me, it represented my ideal of karate (quick, powerful, and efficient technique with no nonsense added for show), and I knew I had to learn this art.”

Passai kata execution at the Hombu Dōjō; same position but different blocks from Itosu’s.

Interview with Shimabukuro Zenpo Sensei

1) Can you explain the reason of the word Seibukan 聖武館?

It means sacred martial arts. It’s composed with the charater (seinaru聖なる). We created this word to signify that the fighting spirit (気負い) takes on a sacred dimension and is inherent to budō.

2) What is for you the most difficult thing to master in karate?

Although one might say that is difficult, we should not complain during training… It’s all about effort. So, I think the hardest thing lies into keeping practicing. When you cannot do a performance, you have to work rigorously until you finally get there, without giving up.

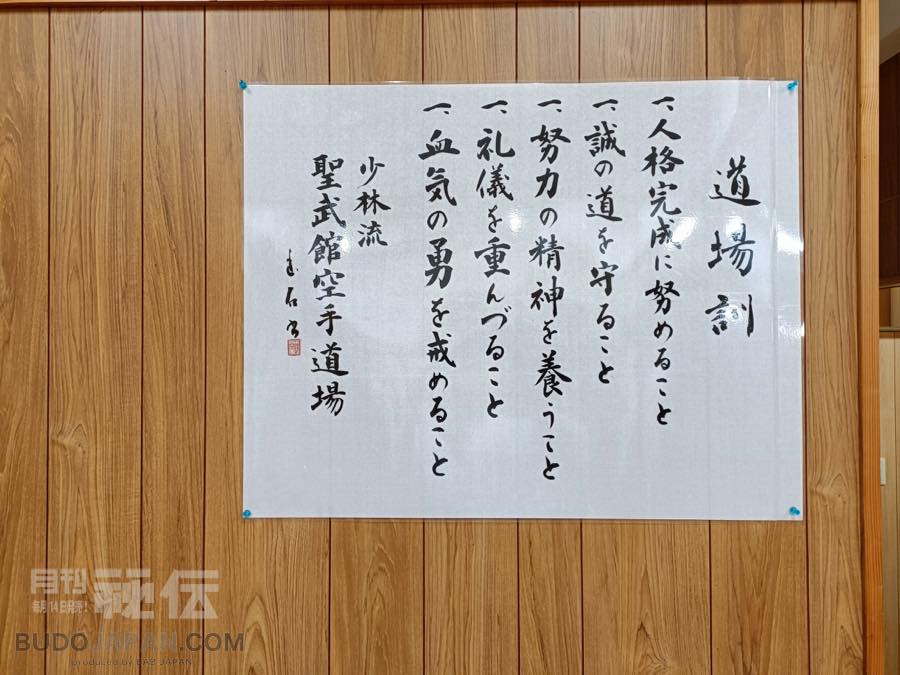

On the Dōjō’s wall, the Dōjōkun (or precepts) are solemnly shown. the fourth column from the right is written as follow “Hitotsu Doryoku No Seishin O Yashinau Koto”.

「一、努力の精神を養うこと」。

“To cultivate the spirit of effort.”

On the Dōjō’s wall, the Dōjōkun (or precepts) are solemnly shown. the fourth column from the right is written as follow “Hitotsu Doryoku No Seishin O Yashinau Koto”.

3) How can karate be useful to someone?

It is important for building self-confidence in young children, and for improving the health of those with frail/weak physiques. Karate is undoubtedly effective in this respect, and cultivates the mind.

4) What are the features of your style compared to others?

We emphasize Posture (sei背) and are particular about stances, positions of the arms, etc. We strive for more complete martial movements.

5) What is your favorite kata?

When I was young, it was Kūsankū and Chintō. Now, I leave those to Zenshun, especially with the jumping kicks.

6) Do you have any project for the Seibukan school?

We have the Seibukan Sixty-two Years Anniversary next year. It was supposed to be Sixty-Years Anniversary, but we could not do it because of the pandemic. We are now expecting many people from the branch Dōjō from all over the world. By gathering many invitees to this event, we plan to share the art as a great memento.

7) Finally, what would be the purpose of Okinawan karate now that war is not as omnipresent as before?

Karate has a duty to preserve peace and friendship. For example, whether you are French or Russian, everyone does karate. We all have a heart and even with martial arts, we can join hands. That is why I’m a pioneer in these diplomatic relations… When I was in my twenties, I came to America to spread my Okinawa knowledge as widely as possible. Then I went to Russia, Africa, Argentina.. It was to help people understand the notion of friendship through the practice of karate. No matter where we come from, it brings us closer together.

Despite our size difference, Shimabukuro Zenpo sensei still exudes the aura of a sacred monster!

Conclusion

After one week in Okinawa, It was with a full mind that I returned to Tōkyō, eager to return to train there. Appetite comes with eating, and this definitely sealed my desire to deepen my knowledge of karate. I would like to sincerely thank the Shimabukuro family for letting me into the Dōjō, and the practitioners for their warm welcome. Also many thanks to Brian Arthur for his trust and kindness, without whom this experience might not have been possible. Mata ne !