Text by Grigoris A.Miliaresis

Despite the rather unorthodox choice of venue (the Nakano Sun Plaza instead of, say, the Nippon Budokan) the Enbu Taikai celebrating the 80th anniversary of Nihon Kobudo Shinkokai held on July 19 this year promised to be huge: 70 of the organization’s 83 schools were going to be there, offering viewers a rare chance to see a generous sample of what koryu budo is today. And remind them that few things are valued more in Japan than tradition -I couldn’t help think about tradition since Nakano has been the home of my ryuha, Toda-ha Buko-ryu for over half a century. My teacher’s teacher’s teacher, Kobayashi Seio-sensei and her successor Nitta Suzuo-sensei have been based there since the mid-1960s and this is where everyone involved with Buko-ryu today and for the last 50 years was (and is) taught.

Tradition is a strange, mysterious and marvelous creature. It can be powerful enough to drive a people for centuries and at the same time, fragile enough to vanish in a few months, weeks, days even. Consider this: we all know about the Great Tokai Earthquake and its prediction theories. What if it happened there and then, that day under the Tokyo Bay? And what if, against all rational probabilities, it hit the Nakano Sun Plaza with the representatives of 70 schools warming up behind the stage or demonstrating on it? What would be the future of these schools with their headmasters or their senior teachers and students gone? How much of that which we call “Nihon kobudo” today would have survived for the next generation?

Why such grim thoughts in such a joyful, hot and bright summer day? Well it has nothing to do with the day: since I came across koryu, almost 25 years ago and since I started actually training in one, exactly 8 years ago, there’s hardly been a day that these thoughts haven’t crossed my mind. For all the toughness they possess and instill to their members, these schools are delicate things open to the misfortunes of which the bards of the past warn us: The sound of the Gion Shoja bells echoes the impermanence of all things; the color of the sala flowers reveals the truth that the prosperous must decline. The proud do not endure, they are like a dream on a spring night; the mighty fall at last, they are as dust before the wind.

We have all read the accounts: a mere two centuries ago there were -in this city alone, not to mention all over the provinces with their private armies- hundreds of schools many of them with thousands of exponents. Looking today at the registries of the Nihon Kobudo Shinkokai and the Nihon Kobudo Kyokai, we see 83 schools in the first and 79 in the second – and many of them are branches of the same school only recently separated not to mention that they coincide. (I haven’t done it yet but at some point I will: compare the lists to see how many unique schools are registered at this time – I’m sure finding that the answer is somewhere between 70 and 80 won’t surprise anyone).

So where are the rest? What happened to all those schools that are featured in books like by Watatani and Yamada’s “Bugei Ryuha Daijiten”? When did they become extinct? And why? And what could have been done to prevent it? And what can be done to prevent the same thing from happening today? It’s no secret that many schools have problems finding students because, frankly, less and less people are interested in investing a good deal of their already insufficient free time in the pursuit of such arcane knowledge. Is there any reassurance that all 70 schools that demonstrated in Nakano that day would still be alive for the 100th anniversary of the Nihon Kobudo Shinkokai? What about the 150th? Or the 200th? These questions keep me up at night and I’m sure they keep up everyone interested in this micro-culture with its deep and tangled connections to Japan’s history.

And this isn’t even the biggest question. The even bigger one is: among the ryuha extant today, how many are really doing budo? Gustav Mahler once said that “Tradition is tending the flame, it’s not worshiping the ashes” so where do today’s schools stand in that dipole? How many still research, still decode the teachings in their scrolls, still try to find the underlying principles that make their material relevant in an era and a society where warriors are almost completely irrelevant (the revision of Article 9 withstanding)? I know for a fact that there are at least a dozen schools that owe their present-day existence to the obsession of charismatic students who joined sometime in the last 30 years and who, through their questioning and pressure, revived not just parts of the curriculum but even the school’s very essence. What would have happened if those individuals had made a different choice? And what happens to the schools that don’t include such people in their ranks? Even if they “survive” to the next century, what will have really survived?

These are all questions that the people in the Nihon Kobudo Shinkokai (and the Nihon Kobudo Kyokai and the various other local kobudo organizations) need to address; it is this writer’s hope that they have been addressing them since their inception –in the Nihon Kobudo Shinkokai’s case, back in 1935, hence the 80thanniversary this year- and they still do. Manned by people who have been living these traditions for decades, in some cases for their whole lives, they are in the unique position of being able to see the big picture, a picture that often starts at the Sengoku Period and, in essence, never ends –only extends in the future. If, as is my assumption, they really care about the flame in these traditions and not just the ashes, they need to take all necessary steps to make sure that this flame is indeed kept alive. And of these steps the enbu are only the first.

The Nihon Kobudo Shinkokai was created in a strange era, an era during which martial values forgotten for almost a century had returned to the limelight. It was an era when political powers all over the war were reshuffling the decks and when, as great Prussian military thinker Carl von Clausewitz famously puts it, war was the continuation of politics by other means. Most of the modern martial arts (and even combat sports like judo and kendo) were created then and the classical arts, having themselves been beneficiaries of the political and social climate (several of them had become involved with the educational system), followed a similar organizational model forming what would have been considered unthinkable in the days of the samurai: an association that would have former enemies sitting next to each other; if the word “enemies” seems an exaggeration, please remember that several of the people who formed the Nihon Kobudo Shinkokai on February 3, 1935 (among them Buko-ryu’s own Murakami Hideo-sensei) did face each other in gekken-kogyo matches.

Of course I don’t mean to imply that those matches were actual duels with the participants wanting to annihilate their opponents. But from discussions I’ve had with people from several schools, I know that antagonism did exist and that the ability to predominate was regarded highly, comparable even to the exploits of previous generations of the ryuha’s exponents in the battlefields. Therefore, the fact that all these antagonistic people managed to sit on the same table, see that they have a common goal (i.e. the promotion of their arts as a whole body of knowledge instead of the survival of each ryuha) and agree to work together towards the achievement of this goal is quite an accomplishment on itself and one the Nihon Kobudo Shinkokai should consider among its greatest.

Another achievement of the Nihon Kobudo Shinkokai I consider worth mentioning is that the organization managed to survive through the turbulent post-war period and especially during Japan’s Occupation by the Allied Forces and the, so-called, “GHQ budo ban”. Even though we now know that the ban was limited in scope, involving for the most part the educational system and the central budo regulating authority (i.e. the Dai Nippon Butokukai), there’s little doubt that the confusion of the times (owing in no small part to the cultural clash between the Japanese and the Occupation forces, the shock from the defeat and the ideas having been formed in the minds of the people due to war propaganda) had made many people question the sanity of continuing their practice, let alone the participation in an organization that according to many (non-Japanese and Japanese alike) had contributed to the propagation of a harmful ideology.

But the Nihon Kobudo Shinkokai managed to come out – relatively – unscathed and after the Occupation was over, to regain its status as an organization preserving and promoting the koryu, the ideal of lifetime education and the cultivation of people’s characters. And while these sound suspiciously like the goals set by other budo organizations after the war and the Occupation, one could argue that when discussing arts of war of the past in the late 20th and the early 21st century, they are as good a way as any to describe what such an organization should and would aim for. All the questions and concerns regarding the present and the future of the koryu that I mentioned earlier can be said to fit within the above mission statement.

Decades came and went, and today the martial arts are as an important exportable commodity for Japan as are electronics or optics – or more accurately as other cultural items like cinema, ikebana or manga. And for the last two decades, thanks to a variety of reasons both directly and only marginally related to them, the old schools have started becoming known as well. Many of them have study groups abroad as well as non-Japanese practitioners studying them on their native soil and there are at least a dozen of them that owe their existence (actual or essential) to non-Japanese who have loved them enough to make their survival their primary goal. At the same time, and equally important, a new generation of Japanese has started seeing them under a different light and has begun studying and researching them using new methods and tools. Perhaps I was too pessimistic before: there’s a good chance that most of the schools we saw in Nakano that day will survive well into the next era.

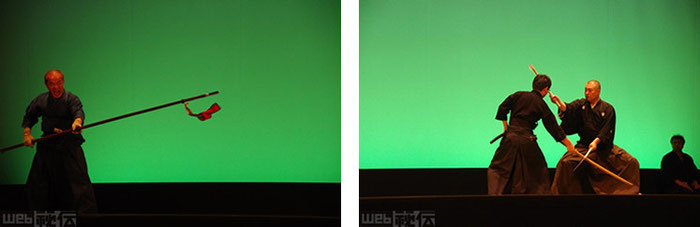

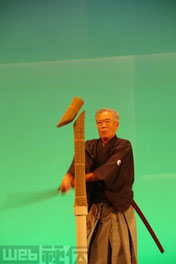

By now you must have figured out that this was not a standard enbu report; “Hiden” has featured many of those in the past and will again in the future. Don’t take this to mean that the enbu lacked merit – quite the contrary: from the moment Ogasawara-ryu took the stage for their ceremonial shots that started the enbu followed by Taked-ryu and their war conches to the moment Shimazu Kenji sensei led the members of Morishige-ryu with their matchlock guns more than five hours later, the demonstration was, for the biggest part, a delight reminding to the viewers that there is still flame in these schools. There is this flame in the flashing swords of Muso Shinden-ryu and the cracking bokuto of the Yagyu Shinkage-ryu, in the swirling naginata of Chokugen-ryu and the piercing yari of the Owarikan-ryu, in the lethal entanglement of limbs of Takenouchi-ryu and in the clicking armor of Yagyu Shingan-ryu, in the precision of Shinto Muso-ryu’s Jo and in the majestic postures of the Kashima Shinden Jikishinkage-ryu, in the elaborate fierceness of Hyoho Taisha-ryu, the soul-piercing kiai of the Shingyoto-ryu and the growls of the Muhimuteki-ryu.

As I mentioned earlier, my main concern is that this flame remains alive. Many of the senior practitioners are well into the seventh decade of their lives and even though such ages don’t mean in Japan the same thing they mean in other cultures, it is a worrying sign – equally worrying is the rather small percentage of people in their 20s or 30s. The schools need to address these matters and so does the Nihon Kobudo Shinkokai, itself on its way to a century of existence. I don’t envy the immense weight the leadership of the organization has on its shoulders: yes, each school can and will take care of itself but in a day and age where traditional culture strives to remain relevant in a globalized society moving in extremely fast speeds (coming from a culture that faces the exact same problem I can certainly attest to that) an organization like the Nihon Kobudo Shinkokai can play a role of utter importance. Its own survival so far could very well be a testimony that it will – I sincerely hope so.

As I mentioned earlier, my main concern is that this flame remains alive. Many of the senior practitioners are well into the seventh decade of their lives and even though such ages don’t mean in Japan the same thing they mean in other cultures, it is a worrying sign – equally worrying is the rather small percentage of people in their 20s or 30s. The schools need to address these matters and so does the Nihon Kobudo Shinkokai, itself on its way to a century of existence. I don’t envy the immense weight the leadership of the organization has on its shoulders: yes, each school can and will take care of itself but in a day and age where traditional culture strives to remain relevant in a globalized society moving in extremely fast speeds (coming from a culture that faces the exact same problem I can certainly attest to that) an organization like the Nihon Kobudo Shinkokai can play a role of utter importance. Its own survival so far could very well be a testimony that it will – I sincerely hope so.Exiting the Sun Plaza Hall we got immersed in an Okinawa fair held on the square in front of the Sun Plaza. People seemed to be having a great time, eating from the food stalls, drinking cold beers and soft drinks to fight the summer heat and dancing to the sounds of the jamisen and the drums. Since this is Tokyo my guess is that most of the people in the crowd weren’t Okinawans but this didn’t matter: they were able to appreciate the beauty of the unique culture of the Archipelago and let it permeate them, if only for a while. Such is the power of tradition: sincere love for something gives birth to the need to keep it alive and to give it to someone else; the recipient, moved by this love and this need, accepts the gift makes it part of his or her life and becomes part of the chain, keeper of the gift and the next giver. Yes, it’s that simple and at the same time so immensely great.

For more photos click here! → http://webhiden.jp/gallery/photo/80_1.php (WEB秘伝)

About the author

About the author

Grigoris Miliaresis has been practicing Japanese martial arts since 1986. He has dan grades in judo, aikido and iaido and has translated in Greek over 30 martial arts’ books including Jigoro Kano’s “Kodokan Judo”, Yagyu Munenori’s “The Life-Giving Sword”, Miyamoto Musashi’s “Book of Five Rings”, Takuan Shoho’s “The Unfettered Mind” and Donn Draeger’s “Martial Arts and Ways of Japan” trilogy. Since 2007 his practice has been exclusively in classic schools: Tenshin Buko-ryu Heiho under Ellis Amdur in Greece and Kent Sorensen in Japan and, since 2016, Ono-ha Itto-ryu under 17th headmaster Sasamori Takemi and 18th headmaster Yabuki Yuji.

http://about.me/grigorismiliaresis