Text by Grigoris A.Miliaresis

In a feature about non-Japanese involved in Japan’s budo, it’s natural that the first article would be about Toda-ha Buko-ryu naginatajutsu. For a small provincial school to have managed to spread all over the world (USA, France, Spain, Greece, Australia) and have in its ranks so many distinguished shihan (fully licensed instructors) is remarkable enough; even more impressive is the fact that the present head of the school in Japan is a non-Japanese, soke-dairi Kent Sorensen a native of Denmark living in Japan for almost three decades and a dedicated practitioner of budo. Sorensen sensei himself will tell his story below, but since the reader might not be familiar with Toda-ha Buko-ryu’s history, perhaps some background might be in order.

According to the school’s records, its founder was Toda Seigen (1519-1590), famous swordsman of the Warring States Period, student of Chujo Ryu and also creator of Toda Ryu. His heirs in the lineage were the lord of Hachigata Castle, Hojo Ujikuni (1541–1597) and his wife, Daifuku Gozen, and from there starts a ten-generation connection to the Suneya clan of Chichibu culminating with the 13th headmaster, Suneya Ryosuke (1795-1877) the man responsible for the school as we know it today and for its name (Mt. Buko is Chichibu’s main mountain). Suneya was an instructor of (among other schools) Kogen Itto-ryu and was also responsible for bringing Toda-ha Buko-ryu to Edo. Naginata was a Suneya family tradition and Ryosuke’s wife, Sato (the 14th headmaster) was renowned for her skill with it.

Toda-ha Buko-ryu continued up into the Taisho period in Chichibu among the Sakai family (renowned for their Kogen Itto-ryu), but what should be considered the mainline moved to Tokyo with Komatsuzaki Koto, who is known to have presented her art before Fushiminomiya Sadanaru in 1908. The next headmaster, Yazawa Isao, was a naginatajutsu instructor at Nihon Joshi Daigaku, the 17th headmaster, Murakami Hideo (1863-1949) was a formidable fighter who participated undefeated in numerous open-challenge Gekkiken Kogyo, “shows” and the 18th, Kobayashi Seio (1900-1984?) a woman born into a family of swordsmen, founding member of the Nihon Kobudo Shinkokai, teacher of thousands and also undefeated participant in matches against sword and naginata practitioners. Kobayashi soke’s successor was Nitta Suzuo sensei (1923-2008), teacher of all present day shihan and with a number of students aside from the late Nakamura Yoichi, the 20th soke of the school who died tragically at the age of 40; students such asSoke-dairiKent Sorensen, shihan Ellis Amdur, shihan Meik Skoss and shihan Liam Keeley. She also had a number of other excellent students to whom she personally gave such high ranks as shihan and shihan-dai: Kini Kuwamori, Shoko Zama, Pierre Simon, Claire Simon and Ron Beaubien.

Shall we start with your budo background?

I started practicing Kyokushinkai karate in Denmark when I was 14. When my dojo closed, I moved to taekwondo, but gradually developed a broader interest in budo and particularly jujutsu; this was pre-Internet, so information about budo wasn’t plenty and at some point I realized I needed to go to Japan. I came in 1987, initially for one year to study jujutsu, but I never left. My introduction to Toda-ha Buko-ryu and Nitta sensei happened by chance: a jujutsu training partner met Meik Skoss and Pierre Simon (now instructors in the US and France respectively) at the 1989 International Budo Seminar, became interested in their school, arranged a visit to the Nakano dojo and when he went, I went along. To be honest at the time I was under the impression that naginata was a woman’s weapon but after talking with Nitta sensei and watching practice, I realized that I’d been mistaken. The brand of naginata Nitta sensei was teaching was not woman’s naginata –it was battlefield naginata, something very different from what I had imagined.

What really did it for me was the practice: it was intense and serious, and pretty soon, I knew I had to learn more about this art. I enrolled the next week and never stopped practicing since –I became a shihan in 2001 and I started teaching under Nitta sensei until her death in 2008 at which point I took over the Nakano dojo. Incidentally, my involvement with Toda-ha Buko-ryu sparked a broader interest in weapons arts and I tried various things before I started training in Ichigido Bujutsu under Shiigi Munenori in 2003 (in which I also hold a full teaching license and currently am the shihan-dai at its hombu dojo).

Besides being an instructor you are also Toda-ha Buko-ryu’s soke-dairi. Could you explain more about that?

At the present time Toda-ha Buko-ryu doesn’t have a soke; this means that I, as its soke-dairi, am the head of the school and it’s up to me to lead and make all important decisions regarding the school and eventually choose the next soke. In important matters, I consult with the shihan –Ellis Amdur, Meik Skoss and Liam Keeley- but the final decision lies with me. I am grateful to them for their support and proud to call them my friends –they are people I respect and whose respect I want to keep.

This was Nakamura sensei’s mandate, his last “will and testament”: for me to lead the school after his passing and to teach and groom its next soke. I have the powers of a soke, but it was his wish (as is ours) for the school’s center to remain in Japan –we don’t want to uproot it and take it to another country. Our intention is for the next soke to be Japanese, and I have a number of Japanese students who hopefully someday will become teachers themselves and one of whom will eventually become the soke.

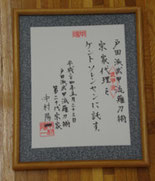

I first met Nakamura Yoichi sensei over 20 years ago, when he was studying at WasedaUniversity. I watched him grow into the man he became and I was honored to be his friend: he was a man worthy of respect and his passing was a hard blow for everyone in the school, not to mention his family as he died at a very young age leaving behind a wife and four children. Two or three months before he died he came to the dojo and announced to us that his intention was that I would be the soke-dairi, the caretaker of the soke position and leader of the school after his death. He presented me with a document written to that effect which he signed and stamped; this leaves no doubt about his wishes which by the way he repeated again when I last visited him in the hospital with the Nakano dojo’s senior shihan, Ellis Amdur.

Theoretically, he could have passed the leadership to one of the younger Japanese members but because our soke had also always being our head teacher, these students were then too young and inexperienced; therefore he chose me as the interim leader with the mandate to prepare and choose his successor. So even though it was never my intention to become the school’s leader, I promised him to do this on his deathbed and it’s a promise I intent to keep. He is not with us anymore but his legacy is and I intent to keep his legacy by keeping my promise to him.

After his death there have been people who have voiced their disapproval with his decision to make me soke-dairi; there have been even people who have encouraged me to step down and there have been people who quite underhandedly have tried to annul Nakamura sensei’s decision, but his decision will stand. Kobayashi sensei as well as Nitta sensei both said that “our business is our business and our business only” (uchi no koto wa, uchi no koto dake desu) so we won’t tolerate anyone telling us what to do –they didn’t either. How could we go against the dead-bed order of our soke! I’m sure no koryu would allow this kind of interference in its business. Fortunately I have gotten a lot of encouragement as well from koryu teachers, both Japanese and non-Japanese. This has taught me a lot about people –I guess you could say it was a valuable experience, a true study of human character.

Toda-ha Buko-ryu is unique in that all its present instructors are non-Japanese. How did this happen?

Well, it certainly wasn’t planned ?it just happened that way. Nitta sensei never thought of people as foreigners or Japanese; only as individuals committed to the school and sharing her care for it; where they came from didn’t matter. What was important was having people loyal to her and the school, and this she reciprocated by also been very loyal to us. Sensei always thought that this is a special school and cared deeply for it and we all admired and shared her love and respect; in effect what we are doing is carrying out her wish for Toda-ha Buko-ryu to live on.

I believe that coming from a foreign culture brings something different to these arts. Have you seen this? What are its possible implications?

Everyone who starts a koryu brings something to the table, not just foreigners. It is essential though, to leave your “baggage” behind and start completely afresh –don’t forget that you are here to learn, not to be judgmental about what is shown to you. You need to let your mind be a “blank canvas”. Of course, there might be a need to make certain adjustments, e.g. Nitta sensei was much shorter than any of us so over the years most of us have started using a longer naginata. But the body dynamics and the basic principles are the same whether you are 150 cm or 200 cm tall –what is different from person to person though is the distance: everyone has their own distance (mine was quite different from sensei’s simply because we were so different in height and reach). The essential thing though, what really matters, is that one stays within the school’s parameters, that what ones does has the “feel” of the school. Sensei never had a problem with individuality; she strongly believed that correct transmission was important but she also strongly believed that there’s room for individuality within the school –hence the expression “kosei wo ikasu” (capitalize on your individuality).

After all these years, I have come to believe that what you should bring to koryu is dedication, an open mind and willingness to learn and that this should extend beyond the dojo. Any serious student of koryu should spend a fair amount of time doing suburi and basics outside the dojo; just going to practice once or twice a week is not enough if you wish to learn and understand koryu. The okugi (secret teachings) is to be attained through tanren, through suburi and basic practice. Of course one can do koryu without making this kind of commitment and still get something out of it –koryu as anything else can be done at many levels but if one really wants to reach the highest peaks, a lifelong devotion is necessary.

We see a lot of people studying more than one koryu –you among them. What are your thoughts on this?

Yes many people do it and I don’t necessarily see it as a bad thing; Nitta sensei never discouraged me from doing it either. If you do more than one school, you need to devote the same amount of time and commitment to each school and not forget that one lifetime will probably don’t be enough to master just one school; therefore trying to master two schools is quite an undertaking. And although there are many similarities in koryu, you must adamantly avoid “blending” the schools you’re doing; if you’re not careful you could easily end up doing “chanpon budo” which is something that should always be avoided. There’s also the issue of mixed loyalties (something that can cause a lot of trouble and hardship) and you also have to make sure that you do it for the right reasons: you shouldn’t be doing it just because you think it’s a “cool school” or because it would be nice addition to your business card.

On the other hand, practicing more than one school certainly offers a wider perspective that might help you better understand the arts you are doing. Most of the practice done in koryu today is kata practice; we go through the different stages of kata practice (shu-ha-ri) in order to get to the inner teachings of the kata, their essence. It takes a lot of hard training and commitment to get through the different stages and to actually understand and apply the inner teachings of kata; I think that as one goes through these stages, having a wider perspective (like the one attained by studying other koryu) is helpful. At the same time one must be objective and unbiased about this.

There’s been a broader interest in koryu, sparked sometime in the last ten-fifteen years. Why do you think this has happened?

I think the Internet and the abundance of information now readily available has played a big role in this. When I started, such information was scarce but now there are even koryu with websites! It is indeed a whole new world. I think there are many people, especially the younger generations who aren’t aware that these traditions still exist; hopefully the Internet and publications like “Hiden” will help change this. These arts are an important part of Japan’s cultural heritage and there’s much to be gained by young people studying these arts.

At the same time we’ve seen a rise of interest for more “applicable” arts. Do you think the koryu are relevant today? What can they offer to modern people?

Again, it’s all up to the individual: you get out of it what you put into it. But there are things in koryu far beyond swinging a sword. For one thing, there’s the aspect of combative awareness, an extension of the general awareness of one’s surroundings that people should have at all times. Zanshin is very important not just in budo but also in life; the concept of seeing everything without focusing on any one thing is something useful for everyone. Nitta sensei often said “budo wa rei ni hajimru, rei ni owaru” (budo starts and ends with respect): this is something people from all walks of life should apply in their daily doings ?proper behavior and respect for others is essential.

After participating in and watching koryu for almost 30 years have you noticed any changes?

One major difference I’ve noticed is that back then (late 80s-early 90s) you could still see some old-timers with a level of zanshin and intensity rarely seen anymore. I guess this is to be expected because someone in their 60s at that time had probably been through the war and the postwar hardships; I find it very inspiring that those people kept practicing through those difficult times and I have a lot of respect for them. Now, of course, we live in much more comfortable times, which is probably why people with that kind of intensity have become quite scarce. But I do believe that through “tanren”, constant and earnest practice, we can also reach their level of intensity and zanshin.

You’ve been doing Buko-ryu for 25 years and have reached its highest levels. Was it worth it?

Absolutely! If I had to do it all over again, I wouldn’t change a thing! Nitta sensei taught me a lot ?not just about budo but also about life- and through Buko-ryu I’ve met some extraordinary people like Nakamura sensei and my fellow shihan. But also it’s the school itself: after 25 years I’m still discovering new things to be learnt and understood. One must never stop being a student ?“always a student, sometimes a teacher” I believe sums it up best. You should always have a humble attitude towards what you are doing, an open mind and never stop learning; there’s no perfection in budo and there’s always room for improvement.

THBR shihan resumes

阿無田 江里須 (エリス・アムダ, Ellis Amdur)

Ellis Amdur (b. 1952) has trained in martial arts since 1968 (13 of these years while living in Japan). He trained in judo, aikido, Muay Thai, Chinese kempo, Brazilian jujutsu and American police combatives and he is a shihan in Araki-ryu torite-kogusoku (nyumon 1976) and Toda-ha Buko-ryu (nyumon 1978). He has dojo in Seattle (US), Athens and Thessaloniki (Greece), Valencia (Spain) and The Hague (The Netherlands). He has made one of his own students, Steve Bowman, shihan?Nitta sensei, with great pleasure at this continuation of her legacy, referred to him as her “first grandchild.” He is an expert in the de-escalation of violent, mentally ill people, having written nine books on the subject and assists businesses who have dangerous employees, people who are being stalked and police in hostage negotiation situations. He is the author of three books on Nippon Bugei: focusing on morality within bugei, koryu and esoteric training (nairiki, kokyu-ho) respectively. He lives in Seattle and his website is at www.edgework.info

マイク・スコス (Meik Skoss)

Meik Skoss (b. 1947) began training in martial arts in 1966 in Los Angeles and in 1973 he went to Japan to continue his aikido training. Since 1976, he studied Shinto Muso-ryu jo under Shimizu Takaji, Toda-ha Buko-ryu naginatajutsu with Muto Mitsu and Tendo-ryu naginatajutsu under Sawada Hanae; at that time he also worked with Donn F. Draeger accompanying him on field trips to Southeast Asia, while in 1979 he began studying Yagyu Shinkage-ryu heiho and Yagyu Seigo-ryu battojutsu under Yagyu Nobuharu Toshimichi. He has also practiced judo, T’ai Chi Ch’uan, Goju-ryu karatedo and is currently training in jukendo and atarashii naginata. An MS in Physical Education and BA in Social Science, he holds ranks in ZNKR jodo, jukendo, aikido (Aikikai), tankendo and atarashii naginata, the shihan license in Toda-ha Buko-ryu and the menkyo license in Shinto Muso-ryu. He lives in New Jersey where he and his wife run a dojo, serves on the local volunteer Rescue Squad, is owner of the premier koryu information website www.koryu.com, publisher of Koryu Books the only publishing house specializing in the classical martial traditions of Japan and Co-ordinator & Technical Director, Yagyukai USA

リアム・キーリー (Liam Keeley)

リアム・キーリー (Liam Keeley) Liam Keeley (b.1951 in Johannesburg, South Africa) started training in Jujutsu at the age of ten, and Okinawa Goju ryu karate from age sixteen. He graduated with a degree in classics from the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, and in 1974 moved to Japan where he trained in Goju ryu Karate at Yoyogi Dojo under Morio Higaonna, and Ryukyu Kobujutsu under Motokatsu Inoue. In 1979 he was a member of the International Hoplology Society’s Field Research team led by researcher Donn. F. Draeger, to Malaysia and Indonesia. He returned to South Africa in 1980 having been graded 3rd dan by Higaonna Sensei and while there studied Social Anthropology, continued practicing and teaching Goju ryu Karate and also learned Yang Style Tai Chi and researched the African combative system, Zulu Stickfighting. He returned to Japan in 1984 after graduating with a BA Hons in Social Anthropology and started Tatsumi Ryu Hyoho under Takashi Kato, Chen style Tai Chi under Hakuei Yamaguchi (in 1985) and Toda-ha Buko ryu naginata-jutsu under Suzuo Nitta (1991-2001). He moved to Melbourne, Australia in 2001 and currently works at Melbourne City Library. His website is at: www.melbournekoryu.com.au

Nakano dojo members’ Q&A

You are Japanese, live in Japan and have trained in other martial arts under Japanese teachers. How was it that you chose to train in a koryu where the teacher is not Japanese?

Seishin

Because I was interested in Toda-ha Buko-ryu’s kagitsuki naginata, I was introduced to the school by an acquaintance. Therefore I knew that Nakamura soke was in Shizuoka and that the Tokyo instructor was a non-Japanese. Frankly I can’t say I wasn’t somehow concerned at first but Sorensen soke-dairi’s personality as well as the depth of his martial arts’ knowledge quickly put me at rest. For over 20 years, he is exerting every effort to protect Nitta soke’s dojo and to uphold the promise he made to Nakamura soke to keep the school alive for the sake of the Japanese.

Kazuhisha Nakajima

I became interested in Toda-ha Buko-ryu after watching a demonstration at the Nippon Budokan. When I entered the school I heard from the late Nakamura soke that Sorensen sensei “might be from Denmark but he is more Japanese than us Japanese”. And witnessing his sense of justice and chivalrous spirit I now believe he is indeed a personification of bushido.

Now that you’ve been training in Toda-ha Buko-ryu for some time, do you see any differences between training under a Japanese and a non-Japanese teacher?

Seishin

I never experienced negative feelings from being taught by Sorensen soke-dairi. Whenever he teaches a new kata he shows it once and then he encourages us to try it; I understand that this was the way he was also taught by Nitta soke ?by watching her very carefully and imitating what he saw- and this is the traditional Japanese way of teaching budo.

Kazuhisha Nakajima

I never got any uncomfortable feeling from Sorensen soke-dairi’s teaching; on the contrary I always have a sense that the he has a deep understanding of Japanese budo’s deeper characteristics. He has accumulated a vast amount of knowledge after studying with Nitta soke for 20 years and he is doing his best to transmit this knowledge to us; I believe that as Japanese we owe a great debt to him and the other non-Japanese shihan for this offer to Japanese culture.

About the author

About the author

Grigoris Miliaresis has been practicing Japanese martial arts since 1986. He has dan grades in judo, aikido and iaido and has translated in Greek over 30 martial arts’ books including Jigoro Kano’s “Kodokan Judo”, Yagyu Munenori’s “The Life-Giving Sword”, Miyamoto Musashi’s “Book of Five Rings”, Takuan Shoho’s “The Unfettered Mind” and Donn Draeger’s “Martial Arts and Ways of Japan” trilogy. Since 2007 his practice has been exclusively in classic schools: Tenshin Buko-ryu Heiho under Ellis Amdur in Greece and Kent Sorensen in Japan and, since 2016, Ono-ha Itto-ryu under 17th headmaster Sasamori Takemi and 18th headmaster Yabuki Yuji.

http://about.me/grigorismiliaresis