Text and photo by Grigoris A.Miliaresis

Personal matters

I like to begin my “Hiden” articles on a personal note but this one, about the Japan Karate Association’s 2018 Spring Joint Training Camp couldn’t have started any other way. You see, Shotokan Karate, as taught by the JKA was my introduction to the world of Japanese martial arts, and my first real contact with Japan’s culture. I only practiced for three years, from 1986 to 1989 but it was enough to fuel my interest for the country and its traditions; in essence, if it wasn’t Tetsuo Otake sensei, now a 7th dan and still Greece’s senior (and only Japanese) karate teacher, you wouldn’t be reading this article!

I like to begin my “Hiden” articles on a personal note but this one, about the Japan Karate Association’s 2018 Spring Joint Training Camp couldn’t have started any other way. You see, Shotokan Karate, as taught by the JKA was my introduction to the world of Japanese martial arts, and my first real contact with Japan’s culture. I only practiced for three years, from 1986 to 1989 but it was enough to fuel my interest for the country and its traditions; in essence, if it wasn’t Tetsuo Otake sensei, now a 7th dan and still Greece’s senior (and only Japanese) karate teacher, you wouldn’t be reading this article!

Makiwara

It’s been 30 years but I still remember everything from that dojo, one that I was lucky enough to be less than a 10-minutes walk from my home: the loud “Osu!” used as greeting, acknowledgment or any other type of communication, the thundering kiai that made the floors tremble, the pounding noises of the makiwara and the bags being hit again and again and again, the smell of sweat and washed cotton and freeze spray and floor wax, the sliding sense of the parquet boards on the feet, the muscle and bone pain from the blocks on the forearms and on the balls of the feet from the kicks… And the first Japanese I’d met, Otake sensei, mild and smiling and encouraging in his broken half-Greek-half-English.

I was really a fanboy back then: as soon as I enrolled, I went out and bought everything karate-related I could get my hands on! A karate-gi, my own makiwara and bag, a pair of nunchaku and a pair of sai and a pair of tonfa (yes, Shotokan doesn’t have weapons –but I didn’t know that yet!) And books and videos (in VHS, of course!) to learn about the old man whose picture has hanging at the center of the dojo, the shomen, Gichin Funakoshi, his successor, Masatoshi Nakayama and the organization responsible for disseminating his style, the Japan Karate Association. And with every book and every video I immersed more and more into this unique chapter of budo history.

A school teacher from Okinawa

Gichin Funakoshi

Even casual observers can see that karate is the odd duck of the Japanese martial arts: punches, kicks, almost zero grappling and solo forms and born in Okinawa, a very remote part of Japan, closer to Taiwan and China than even the southernmost of the main islands, Kyushu. Created by the mid-level aristocratic class of the Pechin, almost certainly integrating elements from the Chinese kung-fu styles it passed on to the general population and became a folk art with every town having its own style. And when its Ryukyu Kingdom was abolished and the islands of Okinawa became part of Japan, a school teacher from Shuri, student of the legendary Shuri-te master Anko Itosu, brought his version of it, the one that would later be called “Shotokan” (his pen name was “Shoto”, the sound of the wind through the pines) to Tokyo.

A collaboration with judo’s Jigoro Kano and the needs of a growing country (and its army) for an effective method of unarmed fighting that could be taught to big groups of people, made Funakoshi’s karate popular –enough to be taught at the Takushoku University were a young student called Masatoshi Nakayama became (by mistake: he was actually looking for the kendo dojo and mixed the practice schedules!) one of its most dedicated students. And the successor of Funakoshi after the death of the latter’s son, Gigo, arguably one of karate’s greatest losses. Under Masatoshi Nakayama, JKA would become the world’s greatest karate organization and its teachers would spread out all over the world to make this art synonymous with budo.

Among the greats of the Nakayama era, Keinosuke Enoeda was the one responsible for the dan grading tests in Greece; I will never forget his presence the first (and last) time I saw him during one of those tests. Even though he was dressed in the navy blue blazer and tie that Japanese martial arts examiners and referees typically wear, you wouldn’t mistake him for a businessman: you could feel in the air around him the power that gave him the JKA All-Japan Championship title in the early 60s, together with Keigo Abe, Hiroshi Shirai and my personal favorite, Hirokazu Kanazawa, helped define what would later be known as the “JKA style”, strong in kata, strong in kumite and with an emphasis to the one strike to end all, the ikken hissatsu.

Among the greats of the Nakayama era, Keinosuke Enoeda was the one responsible for the dan grading tests in Greece; I will never forget his presence the first (and last) time I saw him during one of those tests. Even though he was dressed in the navy blue blazer and tie that Japanese martial arts examiners and referees typically wear, you wouldn’t mistake him for a businessman: you could feel in the air around him the power that gave him the JKA All-Japan Championship title in the early 60s, together with Keigo Abe, Hiroshi Shirai and my personal favorite, Hirokazu Kanazawa, helped define what would later be known as the “JKA style”, strong in kata, strong in kumite and with an emphasis to the one strike to end all, the ikken hissatsu.

At the JKA Sohonbu Dojo

JKA Sohonbu Dojo

And here I was, 30 years later, knocking, as it were, on JKA Sohonbu Dojo’s doors to attend one of its legendary spring seminars where karateka from all over the world come to polish their existing skills and learn new –from 3rd kyu beginners to 7th dan teachers with students who are also teachers, all gathered to practice and communicate and enjoy and celebrate their love for the art of the East China Sea islands that that teacher from Shuri brought to Japan 100 years ago. And as soon as I entered the door of the dojo, it all came back: the loud “Osu!” used as greeting, acknowledgment or any other type of communication, the thundering kiai that made the floors tremble, the smell of sweat and washed cotton and freeze spray and floor wax…

We could choose from six different classes to watch: four on kata (Jion and Bassaidai for 3rd kyu to 2nd dan holders, Gankaku and Tekki Nidan for 3rd and 4th dan holders, Hangetsu and Tekki Sandan for 5th-6th dan holders and above and the same for 7th dan holders and above) and two on kumite (Jiyu Ippon Kumite and Oyo Kumite for 3rd kyu to 4th dan holders and Kihon Kumite and Oyo Kumite for 5th dan holders and above), taught by Naka Tatsuya (7th dan), Ogura Yasunori (7th dan), Izumiya Seizo (7th dan), Chubachi Koji (4th dan), Ogane Yutaro (3rd dan), Ueda Daisuke (3rd dan) –for those wondering why there were 4th and 3rd dans teaching 5th dans, one look at Chubachi, Ogane and Ueda sensei’s record shows that their distinctions in kumite tournaments (mostly the Funakoshi Gichin Cup and the JKA All Japan Championship) make them very qualified. And because not everyone knows that, these are all professional karate instructors!

Ogura Yasunori (7th dan)

Going through all the classes point by point wouldn’t make much sense; besides, the teachers themselves were mostly focused on principles. Of course there was emphasis on details –the positioning of hands in this kata, the stances in that, the distance in one kumite, the angle on the counterattack in another application. But what I found fascinating was how everything they said, pointed out and had the seminar participants work on was both a valid martial arts’ point and a different piece in the puzzle that is JKA’s brand of Shotokan. The whole thing, wasn’t about Jion or Bassaidai or Gankaku or Hangetsu or the particular types of kumite: it was about how to build the perfect karate, step by painful step.

Kata -and more

Take for example Naka sensei’s emphasis on the most basic of all karate techniques the choku zuki front straight punch. Before working on the kata, the 7th dan teacher had the students work both on the punch itself as well as how the body must be positioned to better support it, giving special emphasis to the coordination of the eyes, the pelvis and the feet. Nothing of the above is restricted to Jion or Bassaidai – as Shotokan always argued, the kata are the laboratory where you work on specific techniques so they will appear in your kumite or, if the need arises, in a self-defense situation.

Naka Tatsuya (7th dan)

Or take Izumiya sensei’s emphasis on the hangetsu dachi and the neko ashi dachi stances while teaching –what else?- Shotokan’s most esoteric of all kata, Hangetsu. His painstaking attention to detail had less to do with the execution of the Hangetsu kata itself but with breathing, developing the hara (abdomen) and creating a dynamic tension in the body so that explosive power can be created. What of the above can’t be found in each and every technique of karate or, if we get down to it, of any other martial art? Besides, as the 57-year old multiple kata champion noted, as years pass we become less fast and lest powerful so working on our breathing and internal strength compensates for what nature takes away from us.

Izumiya Seizo (7th dan)

Hangetsu

It wasn’t just the more senior teachers that were focusing on body dynamics: the younger ones (Chubachi, Ogane and Ueda sensei), worked with the seminar participants in what is the second wheel of the Shotokan cart, kumite starting from the basic kihon and going up to the, as the name suggests, more improvised jiyu ippon, through what is probably the first thing that any Shotokan karateka learns, the deep zenkutsu dachi stance as well as the instant tension that needs to be created every time there is a block like age-uke, gedan-barai, uchi uke or soto uke. And this happened with slow and well-targeted exercises that even a 10th kyu would be able to follow.

Chubachi Koji (4th dan)

Ogane Yutaro (3rd dan)

Ueda Daisuke (3rd dan)

Again and again –and again!

I’m no stranger to repeating the basics: I have yet to see any martial art, from the inside or the outside, that doesn’t value them as the treasure of all its knowledge. From aikido’s ikkyo to judo’s osoto-gari to iaido’s mae to to Itto-ryu’s kirotoshi, encoded in these deceptively simple techniques are teachings of a lifetime –we got that! But to see a class of 5th dan teachers and practitioners each carrying on their frayed black belt at least 30 years of experience, working on these basics and trying to organize their body in a way that it would create, as that other great (but often neglected) advocate of karate would say “maximum efficient use of energy” –and not always succeeding what something I didn’t expect.

But they all persevered and they all tried and they all sweated and they all succeeded and they all failed and they all laughed and they all helped each other. And in the end, when they were allowed to work on their jiyu kumite, even though you could feel their need for creative release, the decades of discipline in this unusual art that has bridged the culture of the Asia mainland and that of these here extraordinary

But they all persevered and they all tried and they all sweated and they all succeeded and they all failed and they all laughed and they all helped each other. And in the end, when they were allowed to work on their jiyu kumite, even though you could feel their need for creative release, the decades of discipline in this unusual art that has bridged the culture of the Asia mainland and that of these here extraordinary

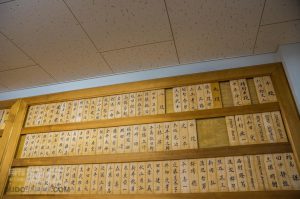

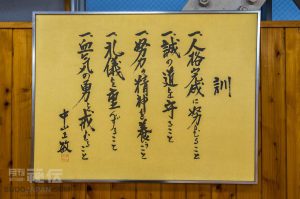

Dojo Kun rules

islands just off its easternmost coast shone through and everyone did the best possible karate they could. If there was any better illustration of the dojo kun rules (striving for perfection, protecting truth, fostering effort, respecting etiquette and refraining from impetuousness) I don’t think I’ve seen it anywhere.

A blast from the past

It’s been years since I’ve stopped being a fanboy but I need to share this: at some point near the door of the dojo I saw something that made me do a double-take. Sitting at a chair with a JKA-logo tracksuit jacket over his karate-gi, holding the seminar notes and watching the lesson, was Masatoshi Nakayama! I couldn’t be mistaken: I had seen him countless times in documentaries and photographs, just like this! The shock lasted for just one second: it was of course Masaaki Ueki sensei, the only face I recognized from my old “Best Karate” series (written by Masatoshi Nakayama), now head of JKA, six years older than his teacher when he passed back in 1987 and looking not a day older than 60. My own 51 years stopped me from asking his autograph but I’ll treasure the memory – I only wish I’d seen him do even a single choku-zuki.

Masaaki Ueki, 9th dan, JKA Chief Instructor

Exiting the small building in Koraku I glanced over the stand with the JKA official goods: patches, pins, T-shirts, bags and even makiwara. I was tempted for a couple of minutes to buy a patch with the double-circle logo, the image that has been the trademark of JKA, of Shotokan and often of karate itself but I resisted it: it would just be for the sake of my 19-year old self and I tend to ignore him as he was a different person than me. I have been in Japan for seven years now and from my place to the JKA Sohonbu Dojo is a train ride less than 20 minutes –it would be extremely easy to go back to where I left things 30 years ago and in a few years get the black belt I so coveted. But I found out quite early in my life that you can’t cross the same river twice so I know that I won’t do it. I needed this visit to the JKA HQ though: it was a good reminder of what it was that made me take up martial arts and what it is that make me continuing them after all these years.

Exiting the small building in Koraku I glanced over the stand with the JKA official goods: patches, pins, T-shirts, bags and even makiwara. I was tempted for a couple of minutes to buy a patch with the double-circle logo, the image that has been the trademark of JKA, of Shotokan and often of karate itself but I resisted it: it would just be for the sake of my 19-year old self and I tend to ignore him as he was a different person than me. I have been in Japan for seven years now and from my place to the JKA Sohonbu Dojo is a train ride less than 20 minutes –it would be extremely easy to go back to where I left things 30 years ago and in a few years get the black belt I so coveted. But I found out quite early in my life that you can’t cross the same river twice so I know that I won’t do it. I needed this visit to the JKA HQ though: it was a good reminder of what it was that made me take up martial arts and what it is that make me continuing them after all these years.

About the author

About the author

Grigoris Miliaresis has been practicing Japanese martial arts since 1986. He has dan grades in judo, aikido and iaido and has translated in Greek over 30 martial arts’ books including Jigoro Kano’s “Kodokan Judo”, Yagyu Munenori’s “The Life-Giving Sword”, Miyamoto Musashi’s “Book of Five Rings”, Takuan Shoho’s “The Unfettered Mind” and Donn Draeger’s “Martial Arts and Ways of Japan” trilogy. Since 2007 his practice has been exclusively in classic schools: Tenshin Buko-ryu Heiho under Ellis Amdur in Greece and Kent Sorensen in Japan and, since 2016, Ono-ha Itto-ryu under 17th headmaster Sasamori Takemi and 18th headmaster Yabuki Yuji.

http://about.me/grigorismiliaresis