Why are Shodo and Budo so compatible?

Shodo and Budo are linked as Do, a Way which takes decades of practice to achieve mastery. Your level of mastery depends on learning directly from a great master. The journey always begins with a single step, and the path never comes to an end. There is a strong emphasis on learning by doing, rather then through theory.

The ultimate purpose is to polish yourself and develop your character through your practice. Both emphasize learning Kata, master forms which are integrated into mind and body through training. In Shodo, the word Shotai superficially means the style of writing, such as Kaisho, Gyosho, Sousho. However the original meaning of the word goes much deeper, and is related to Kata in Budo.

Sho means the written character, and Tai means body. Deep practice involves going deep enough into the original form that it literally becomes part of your body. Just as in Budo, there is an emphasis on correct posture and correct attitude, not only for etiquette, but to become receptive enough to embody the character as you write it.

What do the Sword and Brush have in common?

Although the sword and the brush appeared quite different and function and purpose, there are similarities in the way that the instrument is held. In both cases it must be held lightly but with energy concentrated at the tip. It must be securely aligned with your center, and fully connected to your body. The secret to holding the instrument is found Tenouchi, a word suggesting the particular way in which the palm of the hand contains the scope of one’s power.

Another thing which Shodo and Budo share in common is a highly refined awareness and use of space. In Budo this is called Maai, the proper distance for full engagement. In Shodo the space between strokes and parts of the character, in fact the space between characters in between lines is considered just as important as the strokes themselves. The negative space is actually what defines the visible strokes and characters. As you become aware of and work with negative space, it entirely changes the placement of strokes and the intervals in which to write them.

Breathing and rhythm Hyoshi are also quite important, and so subtle that they can only be addressed after the Kata and forms are mastered at a basic level.

Is the brush like a sword for the mind?

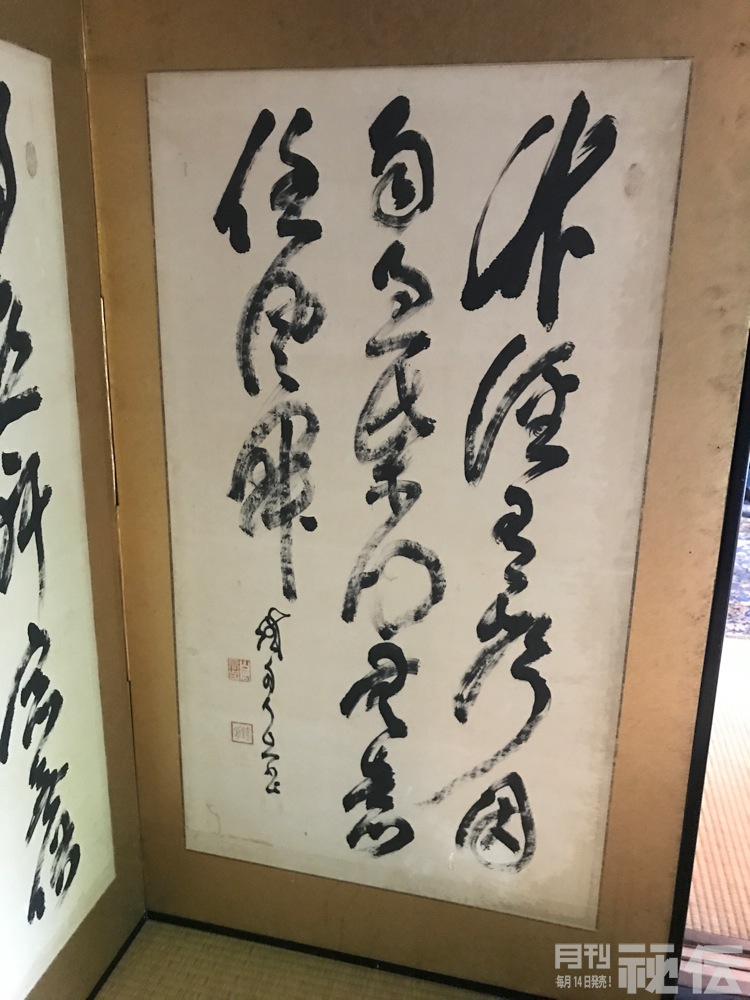

Sword Masters in the past such as Miyamoto Musashi and Yamaoka Tesshu also became dedicated to the art of Shodo. Ueshiba Morihei, the founder of Aikido, in his later years took up the study of Shodo from one of his top students Abe Seiseki, because it made visible the beautiful lines and rhythms of Ki that are found in Aikido.

What is it that these great Budo masters sought in the art of Shodo? Surely it must have been in the way that it makes the mind visible through traces left by the movement of the body. Sho wa Hito Nari, a person’s character is revealed in their written hand.

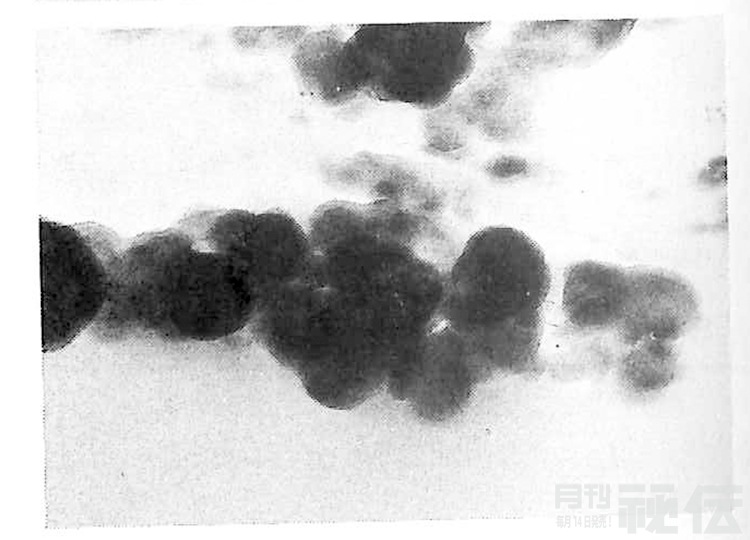

It is not only the outward balance and form of the character that they are seeking, but rather the spirit or soul which embodies it. In Shodo this is expressed in two ways, line quality Senshitsu and Ki connection Kimyaku.

The quality of the line is something that can be seen by a trained eye, and usually is judged by subtle gradations and control, a lack of hesitation, and a feeling of life energy pulsing in the stroke. This has even been verified scientifically by studying the beautiful alignment of Sumi particles seen with an electron microscope, in the works of great masters like Yamaoka Tesshu.

Kimyaku is the lifeline running inside and also between strokes from beginning to end of the composition. It is the quality of unbroken connection, similar to that found in music which makes the peace and integrated whole. It cannot be faked, and it can only be seen if you know how to enter the work by painting it with full attention and engagement.

Kimyaku is the lifeline running inside and also between strokes from beginning to end of the composition. It is the quality of unbroken connection, similar to that found in music which makes the peace and integrated whole. It cannot be faked, and it can only be seen if you know how to enter the work by painting it with full attention and engagement.

Because it leaves invisible traced it lasts for centuries, it can be appreciated by people born long after it was written. This is why a serious study of Shodo always begins with studying the calligraphy of the ancient masters.

What can we learn from the Calligraphy of Sengoku Samurai?

For a Budoka there must be further lessons in studying the calligraphy of the Samurai. Much has been written about the samurai, and famous samurai generals have been depicted of in novels, Kabuki drama, and film, sometimes more of a reflection of the popular view, than of the person who originally wrote the calligraphy.

Through calligraphy however we have a unique and fresh way of experiencing the presence of the original samurai who wrote it. Like a recording of a voice nikusei, the traces left by the brush nikuhitsu are a direct expression of the person’s mind and body, and not an interpretation penned by observers sometimes centuries after their death.

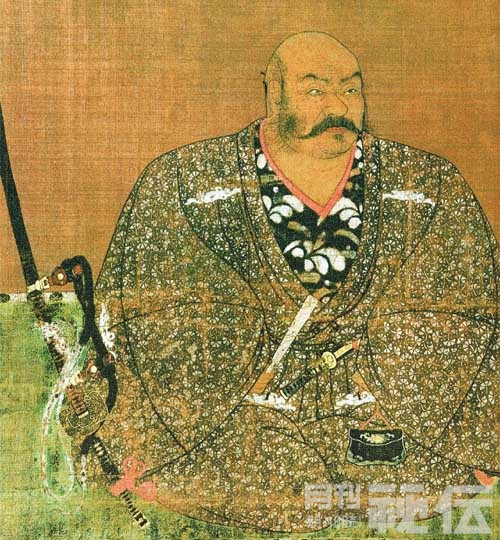

Contrast the qualities evident in the brush rating of archrivals Takeda Shingen and Uesugi Kenshin (see illustration).

Takeda Shingen was known as the carnivorous Tiger of Kai, famous both for taking what he wanted, and also for his popularity and skilled communication with his 24 generals. He was also known for his flamboyance and powerful appearance.

Takeda Shingen was known as the carnivorous Tiger of Kai, famous both for taking what he wanted, and also for his popularity and skilled communication with his 24 generals. He was also known for his flamboyance and powerful appearance.

Uesugi Kenshin was known as the undefeated Dragon of Echigo, believed himself to be the embodiment of Bishamonten, the God of War, and engaged Takeda Shingen five times at Kawanakajima. He combined determination and flexibility in his approach based on his strong belief that he was the God of War.

Uesugi Kenshin was known as the undefeated Dragon of Echigo, believed himself to be the embodiment of Bishamonten, the God of War, and engaged Takeda Shingen five times at Kawanakajima. He combined determination and flexibility in his approach based on his strong belief that he was the God of War.

By closely examining the calligraphy which they wrote, and also by attempting to copy it yourself using a brush, you gain a brief but intimate sense of what it was like to be in the presence of these men.

What lessons can be learned from Shodo and Budo?

One of the key lessons that we can learn from both Shodo and Budo is how to learn. In the modern world people tend to resist the idea of learning by copying, but the roots of learning begin with imitation (maneru manebu). It doesn’t end there however because the learning process proceeds from entering the Kata and then becoming free of it. In the words of Noah Master Zeami, Shu Ha Ri.

Traditionally these arts were not taught so much is absorbed through observation and feedback. The idea of Hiden does not mean secret, so much as hidden, inside the Kata and characters, and discovered through training and close observation. Miyamoto Musashi distinguished between Ken no Me and Kan no Me. In the Traditional Arts students are encouraged to learn by observing, Mitori Keiko.

In both Shodo and Budo the quality of training and performance is judged not by talk Kuchisaki or technique Kotesaki, but by qualities such as Shinken, Honkido, Kokoro. These are lessons that should also apply to the way that we work and live.

Training builds character, Sho wa Hito Nari.

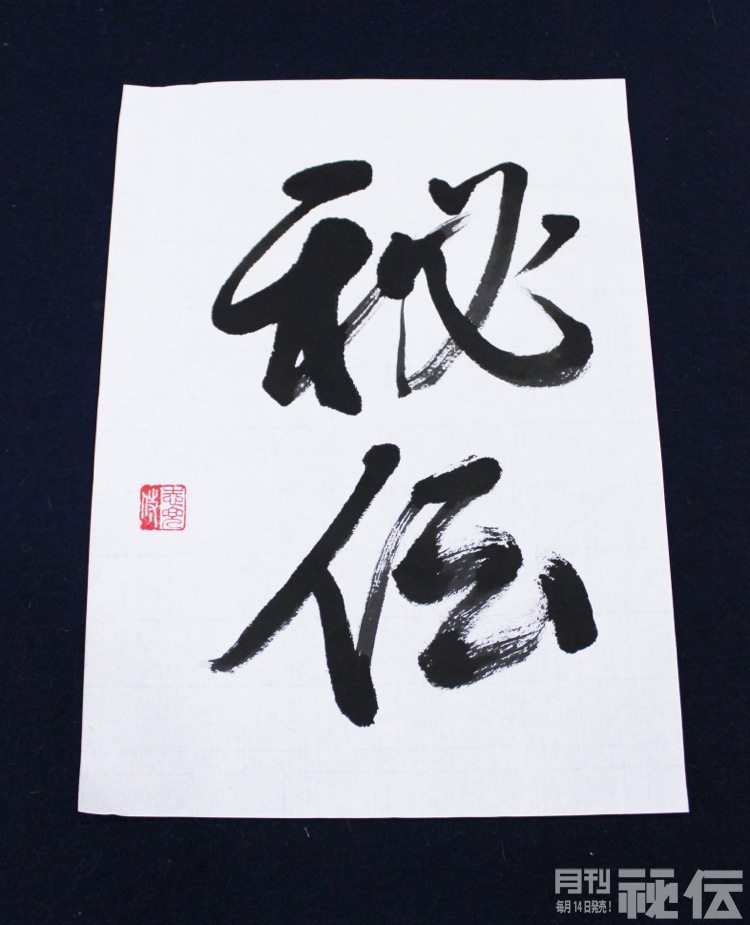

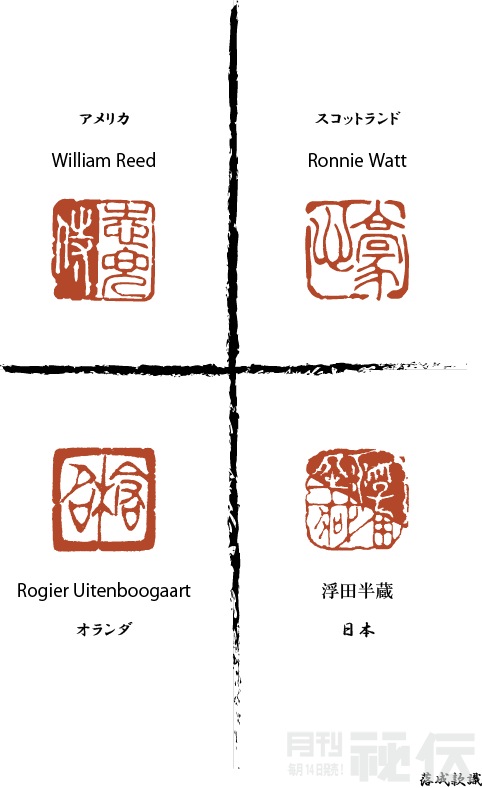

Mission and Meaning in the Seal

In the modern world hanko are used as an official seal in place of a signature. A seal can be registered or decorative, but for the most part they are used to render the person’s or company’s actual name in an old-style script that is difficult to copy.

Considering the importance of her name, and the aesthetic appeal of the Rakkan, I have begun commissioning Rakkan for people of a very special character, including personal friends in the martial arts. (See illustrations)

Ronald Stewart “Ronnie” Watt is a Scottish 9th-Dan Master of Shotokan Karate. He has won numerous awards for his contribution to the world of Karate, and was granted the Order of the Rising Sun it’s golden and silver rays. He also established the Scottish Samurai Shogun Awards, through which he grants recognition to people who have contributed to education and awareness of martial arts in Japanese culture. His seal reads, Samurai of Peaceful Helmets, fitting his lifelong mission.

Ukita Hanzo, head of the IGA NINJA clan and Asyura Ninja performance group, has been highly acclaimed for his physical aptitude and impressive NINJUTSU repertoire both domestically and internationally. His seal reads Ukita Hanzo, and the colors cross boundaries, fitting of a Ninja.

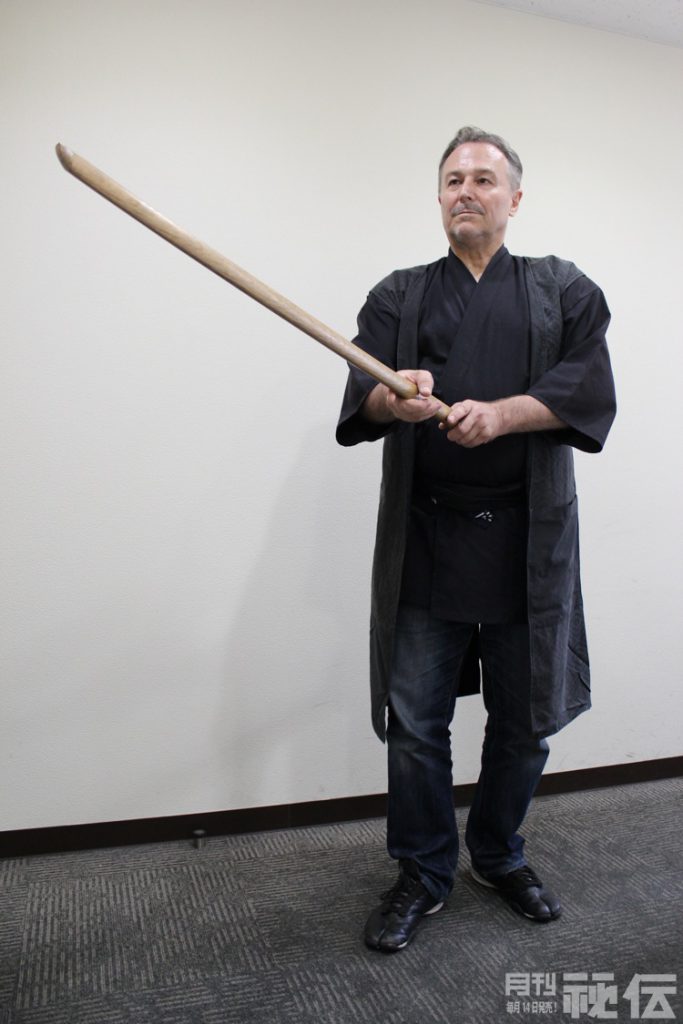

Rogier Uitenboogaart is in Dutch craftsman who has devoted three decades to the art of traditional Washi papermaking. His name has a Germanic roots, meaning “Famous Spear,” rendered Meisou for his Rakkan, and fitting is fine work as a craftsman a Japanese tradition.

Each of these people are performing at the top of their craft, and in that sense are truly brothers of the seal. Most Calligraphers have their own seal, which sometimes contains a message related to their mission. Budoka would likely be interested in having a personal seal to represent their own mission.