Text by Antony Cummins

It is said that Tokugawa Ieyasu – the shogun of all Japan – once turned to his retainers while attending the theatre and proclaimed that it was almost time to prepare the bamboo for the banner poles. What could he have meant by that? Japanese military equipment is not just interesting from a technical perspective, but also has a fascinating spiritual and ritualistic aspect. Why was a garden hoe used as a crest on a commander’s helmet? How did the colours of lacings interact with the colours of armour plates? And how did the spirit of the god of war imbue the samurai with power? The answers to these questions, given below along with a selection of other fascinating details, give colour and depth to our image of the samurai.

Two basic forms of samurai armour

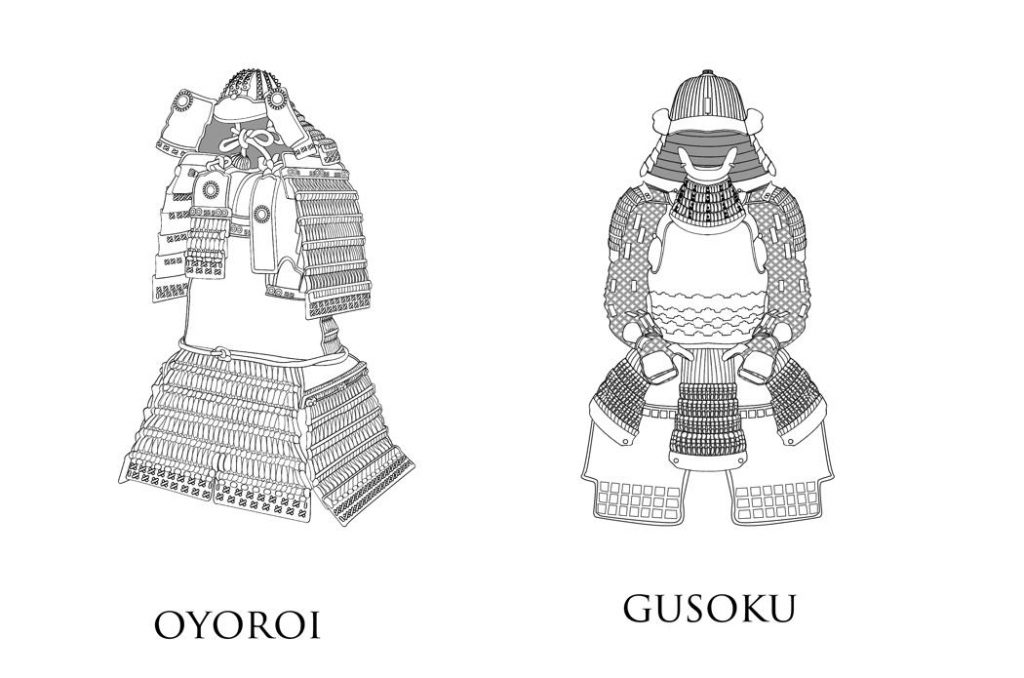

There were two categories of samurai armour: the archaic oyoroi armour and the more compact armour known as gusoku.

Red line on a spear

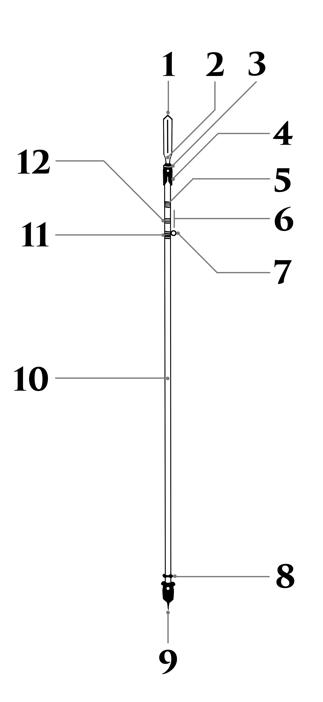

A red line is often seen painted in the groove of old spears. This line was the sign of a warrior of excellence and was used only with permission. If you see a Japanese spear in a museum, look out for the ring at the bottom of the shaft, which stopped the spear splitting when moist, as well as a ring that prevented blood from dripping down to the hands, and a further ring with an eyelet for attaching a troop or personal marker.

The Five Elements

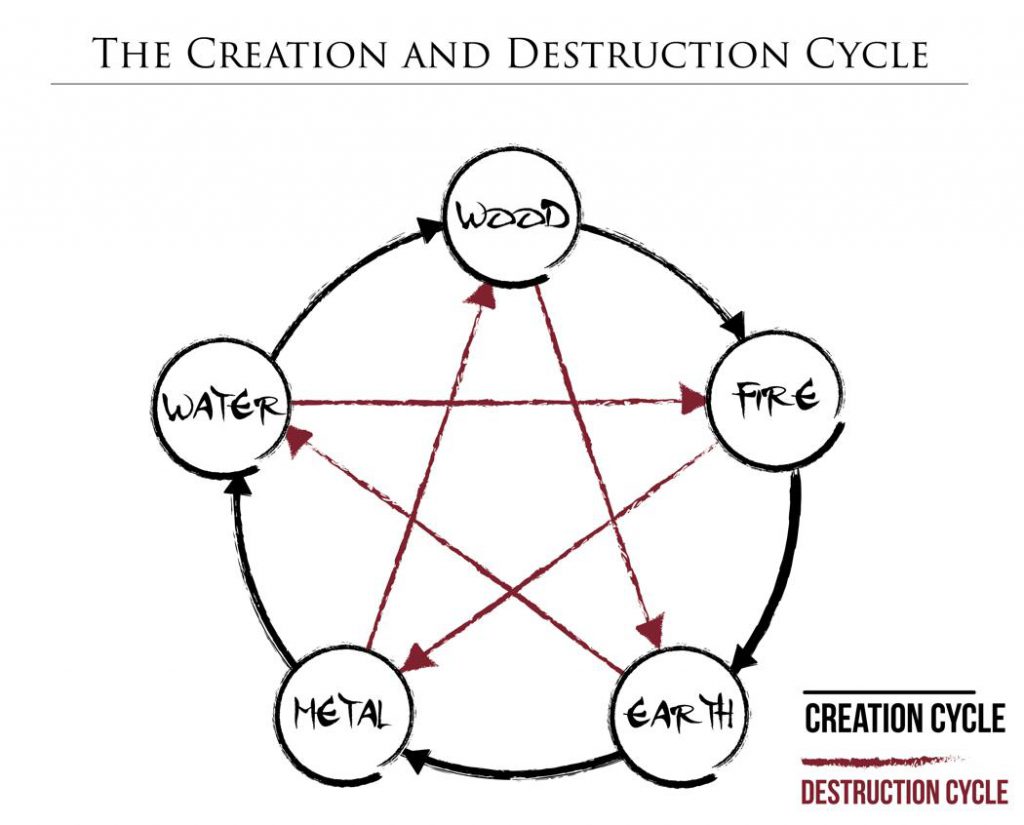

The Taoist concept of a universe made up of yin (negative energy) and yang (positive energy) is played out in the Chinese version of the Five Elements theory, in which wood, fire, earth, metal and water interact in the Cycle of Creation and the Cycle of Destruction. Samurai armourers took into account this complex theory, which was a core part of Japanese life. The colours and ornaments of a set of armour, for example, were carefully chosen to avoid any clashing on a cosmic level and to work together to generate the correct energy. Each element was represented by a colour, such as black for water and yellow/gold for earth. The colours of the thread and of the plates they held in place were expected to work in harmony, while the gold or silver vertical bands on the helmet – which represent the sun (yang) or the moon (yin) – had to be of the correct number to work in harmony with the armour. The bamboo used for the banner pole had also to be of the correct element and direction of growth, so when Tokugawa Ieyasu said it was almost time to prepare the bamboo for banner poles, he meant that it was almost the 15th day of the 8th month in the Chinese calendar – a time of power.

The Taoist concept of a universe made up of yin (negative energy) and yang (positive energy) is played out in the Chinese version of the Five Elements theory, in which wood, fire, earth, metal and water interact in the Cycle of Creation and the Cycle of Destruction. Samurai armourers took into account this complex theory, which was a core part of Japanese life. The colours and ornaments of a set of armour, for example, were carefully chosen to avoid any clashing on a cosmic level and to work together to generate the correct energy. Each element was represented by a colour, such as black for water and yellow/gold for earth. The colours of the thread and of the plates they held in place were expected to work in harmony, while the gold or silver vertical bands on the helmet – which represent the sun (yang) or the moon (yin) – had to be of the correct number to work in harmony with the armour. The bamboo used for the banner pole had also to be of the correct element and direction of growth, so when Tokugawa Ieyasu said it was almost time to prepare the bamboo for banner poles, he meant that it was almost the 15th day of the 8th month in the Chinese calendar – a time of power.

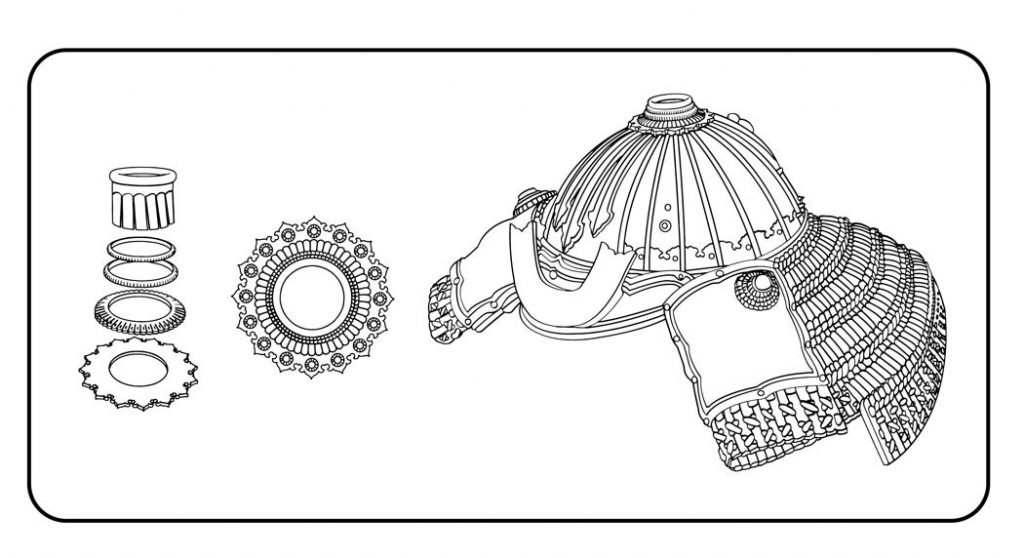

Helmet crest

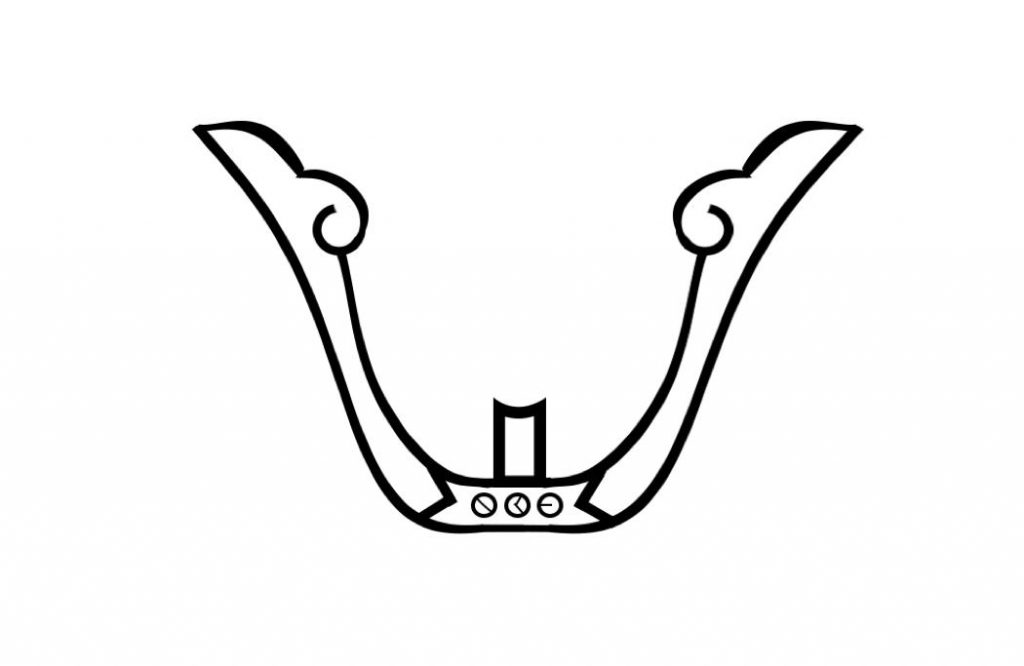

The garden hoe crest, often gold/yellow, represented the centre of all things in Five Elements theory and was usually adorned with a rising dragon, making it the symbol of a leader.

The garden hoe crest, often gold/yellow, represented the centre of all things in Five Elements theory and was usually adorned with a rising dragon, making it the symbol of a leader.

A golden/yellow garden hoe represented the element of earth, which according to tradition was the element at the centre of all other elements, while the dragon was a symbol of rising chi energy; the overall meaning was that a leader was the central figure who commanded all others with the power of a rising dragon.

The seat of Hachiman

The ventilation hole at the apex of the helmet was known as the seat of the god Hachiman and represented a boundary between heaven and earth. It was said that through this hole came a giant war serpent deity with 98,000 scales, imbuing the warrior with courage. Small cloud-like decorations on the helmet further denoted this celestial division. A samurai should never put his finger in the hole of the helmet, unless taking it off to commit ritual suicide, and must never show the inside of the helmet lining except for in times of surrender.

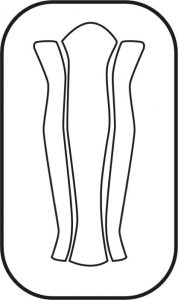

The crown of the king of hell

Leg greaves ranged from cloth with protective metal or bamboo vertical splints to fully enclosed and sculptured leg encasings. Each had a rubbing patch on the inside, to protect the horse and avoid causing damage when they knocked against each other. The greaves of a mounted warrior had knee guards with three mounds, said to represent the crown of the king of hell, while greaves for foot soldiers had no knee protection so as not to become an annoyance when walking.

Leg greaves ranged from cloth with protective metal or bamboo vertical splints to fully enclosed and sculptured leg encasings. Each had a rubbing patch on the inside, to protect the horse and avoid causing damage when they knocked against each other. The greaves of a mounted warrior had knee guards with three mounds, said to represent the crown of the king of hell, while greaves for foot soldiers had no knee protection so as not to become an annoyance when walking.

Overall, a samurai had to consider his status, his past achievements and his personal connection to the Five Elements when constructing or purchasing armour. To wear the wrong lacing, to wear something beyond his station or to calculate the incorrect spiritual relationships of colour and style could all lead a samurai into disaster, but getting it right would set him apart as a man of worth. To find out more, have a look at Book II in the Book of Samurai series: Samurai Arms, Armour & the Tactics of Warfare.

About the author

Antony Cummins is a researcher and an author focusing on the historical reality of Japanese samurai and ninja. He is the head of a small team that translates and publishes historical texts on Japanese military culture and tactics, and has published many books on Japanese military history. He has worked for multiple TV documentary productions, including for the Smithsonian, and is the leader of a project seeking to revive the samurai school of war known as Natori-Ryu. For more information and free download samples visit: www.natori.co.uk

Antony Cummins is a researcher and an author focusing on the historical reality of Japanese samurai and ninja. He is the head of a small team that translates and publishes historical texts on Japanese military culture and tactics, and has published many books on Japanese military history. He has worked for multiple TV documentary productions, including for the Smithsonian, and is the leader of a project seeking to revive the samurai school of war known as Natori-Ryu. For more information and free download samples visit: www.natori.co.uk