(Left to right) Nagatsuka Masaaki of the Ginsenkai, Shimazu Kenji of Morishige-ryu, Grigoris Miliaresis and Uchi Kanefusa of the Oukatai

Text by Grigoris A.Miliaresis

A land of fire

Fire is everywhere in Japan: manifest in the center of its flag and hidden deep under its emblematic mountain, stirring in the heaths that make tea and rice and sake to feed its people and dancing in the furnaces that change iron into steel for their swords and knives and tools. It’s one of the five elements that, according to its philosophy, make up the universe, process the food in the human body and represent the emotional drives that make these humans want to progress. It’s in the fantasy of the old myths with Kagutsuchi representing it’s malevolent side and Kojin its benevolent and in the reality of historical facts, kept alive every time a neighborhood group is doing the rounds hitting the clappers and reminding people to be aware of it.

Hinawaju (long Japanese matchlock)

And fire is in the heart of that most important and at the same time most overlooked by pop culture of the samurai weapons, the matchlock. Both the real traditions of the Edo Period and the invented ones of the Meiji Period have elevated the sword to a legendary status as “the soul of the samurai” but even a superficial read of Japanese history from the mid-16th century onward is enough to dispel any doubts on the matter. The two matchlocks that arrived in the island of Tanegashima, southeast of Kyushu on September 23, 1543 (the “day that Europe came to Japan” as one historian puts it) where instruments of a change in Japanese history so deep and wide that it’s hard to fathom –especially when you have grown up with preconceptions about how the bushi of the Sengoku Period used to fight.

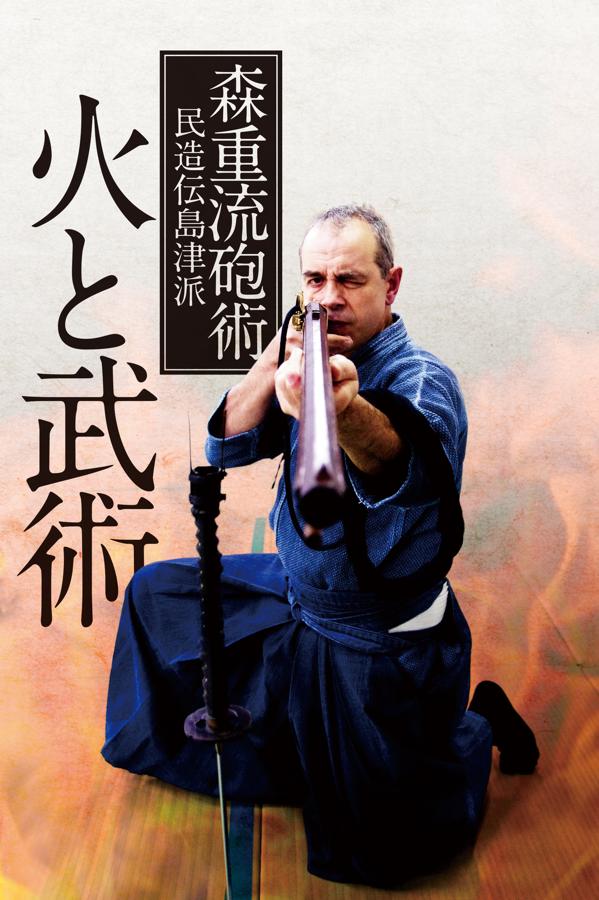

Shimazu Kenji of Morishige-ryu and Yagyu Shingan-ryu

The obvious answer though is that people are people and they will fight using anything what gives them an advantage. Early bushi fought with bows and arrows, their descendants with lances and their descendants with matchlocks, and strategy and tactics is how wars have been won since the time of Alexander the Great. But there is art in the use of the matchlock –as there is art in anything in Japan- and to understand this, I had to come here and see how matchlocks are used. And like most people who get in touch with the koryu bugei world, my first exposure to the 21st century incarnation of this 500-year old legacy was through Morishige-ryu and especially as taught by Shimazu Kenji, known to most people (and me until that time!) from his work in the dissemination of Yagyu Shingan-ryu.

There is a reason Morishige-ryu ends most big koryu bugei demonstrations: nothing could follow it! From the visual with the member’s spectacular clothes, some in armor and some in aristocrats’ garments, to the aural, when the guns fire, to the olfactory when the air is filled with the sulfury smell of the black powder, the impression to the viewers is so strong that it needs time to settle. Add Shimazu-sensei’s explanations of what is happening and why –something rather unusual for big demonstrations but extremely useful, especially in the case of a school where, for obvious reasons, everything is performed solo and you end up with an experience that takes a while to get digested. And one that if you have even the slightest interest in guns will haunt you: I can say with absolute honesty that since that first demonstration at the Meiji Jingu, seven years ago, seeing the school from the inside has been one of my most, ahem, burning desires.

Morishige-ryu Hojutsu at the 2017 Meiji Jingu Shrine Kobudo Enbu Taikai Demonstration

Lets talk guns

One small interlude to explain where I come from: like most Greeks, I have served in the army (Greece still has a conscription/national service system) and was trained in the use of the H&K G3 select-fire battle rifle, the M1 Garand semi-automatic rifle and the Colt M1911 pistol and, because hunting 12-gauge shotguns (pump action, semi-autos and doubles) are legal in Greece, I have shot all of them several times, usually in target shooting and occasionally hunting; I don’t like hunting now but there was a period in my late teens-early 20s that I tried it, mostly because I liked shooting guns. Also, that same period, I tried some 10-meter air rifle shooting and had a few airguns (also legal in Greece) and a 9mm “gallery gun” which I also used for target practice; in all, I wouldn’t call myself an experienced shooter but I wouldn’t say I’m completely clueless either. And frankly, time and money permitting (shooting is a rather expensive hobby) I would gladly get more involved.

Tanju (short Japanese matchlock)

But matchlocks I haven’t shot –there aren’t any in Greece: the oldest guns you can find are flintlocks but those haven’t been fired since the days of the Greek War of Independence in the early 19th century. Actually, until I came to Japan and started visiting antiques stores and sword expos, I hadn’t even touched one so I didn’t really know what to expect when we decided to make this “Koryu Experience” about Morishige-ryu and its method of using these weapons. And finding out that because Japan’s law prohibits the construction of new ones, all the weapons Morishige-ryu and the other hojutsu (gunnery) schools use are 16th , 17th and 18th century antiques didn’t make things any easier. So I was going to be handling things that would normally belong in a museum –that’s not a very comforting thought! Are these guns really functional?

Sanganju (early medieval Chinese hand cannon)

Enter Shimazu-sensei and his student (and now a Morishige-ryu teacher in his own right) Uchi Kanefusa-sensei: they, with the help of Nagatsuka-sensei of the Gisenkai and Nishiyama-san, Uchi sensei’s apprentice, were our guides to an exciting crash course lasting over 20 hours spread over five days, at Shimazu sensei’s office and his dojo in Machida, at Uchi sensei’s home and workshop and at a firing range in Tochigi which would answer the question with a loud (a very, very loud) “yes”. A crash course in history and the art (and science) of hojutsu, starting much earlier than the founder of the school, Morishige Subeyoshi and his times (1759-1816) and going back to the Chinese teppo hand cannons of the 13th century and stretching to the bakumatsu period and a percussion rifle belonging to Kondo Isami of the Shinsengumi (part of Shimazu sensei’s collection) –with a brief stop at Navajo Country, Arizona!

Percussion rifle belonging to Kondo Isami of the Shinsengumi

Sashibi-shiki kaho (early medieval Chinese hand cannons)

Examining Morishige-ryu documents at Shimazu Kenji ‘s office

13th century grenade

Scroll depicting the 13th century Mongol Invasion of Japan

Numa Subeyoshi: The man who studied the gun

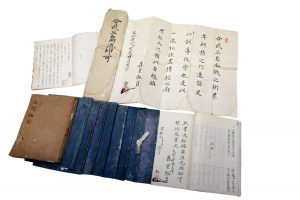

Densho (documents) of Morishige-ryu (Gobu Mishima-ryu)

his series is about how it feels to be part of the ryu we visit so I won’t get much into the school’s history. The brief version is that it starts with Numa (Morishige) Subeyoshi from Yamaguchi Prefecture who in the early 18th century, when he was 18 years old, started a quest to study as many methods of (mostly naval) warfare and strategy he could. He traveled all over Kyushu studying, among others, Asaka-ryu, Nakajima-ryu, Engoku-ryu, Kinden-ryu, Koshu-ryu, Echigo-ryu, the Gobu Den-ryu of Yamamoto Ryoichi, and the Hashijume-ryu Gungaku of Hashijume Manemon Korenari from Kishu and in the end created his system called Gobu Mishima-ryu, the school that his son would later call Morishige-ryu in his honor. What is really interesting is that the school continued for another three generations and then got lost only to surface later through the efforts of avid gunnery researcher, champion shooter, JOC member, Olympic team coach and president of the National Rifle Association of Japan, Minoru Anzai.

Morishige Tamizo

Through the efforts of Minoru Anzai, the seventh head of the Morishige family, Tamizou Morishige got involved in the resurrection of his legacy and Shimazu sensei was part of this effort, hence his naming his interpretation of the school, “Morishige-ryu Hojutsu Tamizou-den Shimazu-ha”. And when I say “part of this effort”, one look at both the written material in his possession and at the breadth of his practical knowledge of the weapons, the techniques and the tactics Morishige-ryu teaches, is enough to realize that he got really involved with the fiery passion and the intensity he’s known to confront everything he does. The two afternoons we spent in his office sitting down in the midst of hundreds of textbooks from the first generations of the school’s headmasters were a real fountain of knowledge.

Morishige-ryu

Tsubadai shooting position

The curriculum of Morishige-ryu is quite extensive: during the time we spent with Shimazu, Uchi and Nagatsuka sensei, we only went over the Reishiki Shaho Kata (where the student learns how to enter the shooting range and how to behave when holding a weapon and when facing a friendly dignitary in contrast to when he goes to battle) and the seven Shuren kata (Ihanashi no kata, Moroorihanashi no kata, Hizadaihanashi no kata, Gyakuhiza no kata, Chuhanashi no kata, Koshihanashi no kata and Tachihanashi no kata) in their application for the long gun and the short (what we would call a “rifle” and a “pistol” respectively although the term “rifle” doesn’t really apply to the matchlock since they don’t have actual rifling in their barrels). These kata teach the exponent how to shoot from basic standing and sitting or squatting positions and they are surprisingly similar to modern shooting techniques –on the other hand considering the extreme practicality of the matter, perhaps not that surprising.

Shiroue shooting position

It might not be apparent in their demonstrations but as happens with most koryu, everything in Morishige-ryu’s techniques and kata is functional. The way of walking allows the exponent to move effortlessly on an uneven battlefield, the way of turning after a shot allows them to bring the gun to a position from which they can easily reload, the placing of the elbows close to the body supports the weapon better since it’s held on the cheek and not touching the shoulder joint (the weapons’ stocks don’t have butts allowing for better use at any angle even when wearing armor) and the positioning of the hands allows for better squeezing of the trigger from different angles – that’s the reason Japanese matchlocks’ triggers are spherical: you don’t need to wrap your index finger around them to squeeze it. Using his knowledge of human anatomy that comes from his profession (he’s an osteopath) Shimazu sensei shed some more light into details such as the position of the weapon in specific points of the hand (or, amazingly, the leg!) for better support from protrusions of the bones.

The spherical trigger of the Japanese matchlock

Specific positionining of the gun for better support from bones’ protrusions

The weapons’ stocks don’t have butts allowing for better use at any angle even in armor

Yondan Hanachi no Kata

Fire!

Uchi Kanefusa at the shooting range in thick cotton keikogi

Morishige-ryu banner

But I guess what you really want to know though is what it feels to shoot a matchlock, right? (At least that’s what I wanted!) Thanks to Uchi sensei, a trained gunsmith whose interest for guns led him to the US where he trained as a silversmith with legendary Navajo artist Thomas Curtis and back in Japan where he learned the art of repairing matchlocks from a Tohoku region artisan, we went through the whole process: from melting lead to make bullets (11 and 18 mm to be exact), to lighting tinder with a steel and flint, lighting a match cord, securing it in the serpentine, loading the priming powder in the pan, and the propelling powder and the bullet in the barrel to actually shooting. And yes, it is exhilarating –as exhilarating as the Morishige-ryu demonstrations are, but more since this time the explosion of the powder, the light and the sound and the smell of sulfur is much closer as is the gun’s kick which, although not as bad as I thought (at least with the 11mm bullet) it isn’t exactly negligible either, especially considering that it’s directed on your cheek instead of your shoulder as happens with modern guns! Incidentally, when the priming powder ignites in the pan, the sparks fly all over the place –you can’t see it in the demonstrations but the Morishige-ryu exponents’ (usually) silk demonstration kimono have tiny holes from them. (Honoring a tradition going back to the Edo period firemen who first used them, Morishige-ryu shooters always wear thick cotton keikogi in the shooting range to avoid having their clothes burned!)

Koyaku-ire (priming powder flask)

Hayago and Doran (carrying box for proppeling powder flasks)

Casting bullets

Handmade bullets (18mm and 11mm)

Securing the lit match cord in the serpentine

Hizadai Hanachi no Kata

Rikinawa shooting position

Shiroshita shooting position

Afterburn

Still, as I wrote in the beginning there is art in this, well art. There’s an incredible amount of detail and Shimazu and Uchi sensei’s guidance opened our eyes to even a small part of it. Unlike modern warfare, and much like the sword, the spear or the naginata, firing a “hinawaju” (matchlock) demands a level of involvement that goes way beyond the ceremonial firings of these weapons often seen in folk festivals around Japan. This is an actual martial art, perhaps even more so than others: even though its present-day form is a reconstruction owing much to the combined efforts of researchers like Shimazu sensei, there’s no doubt that it comes from eras where these same weapons, changed the way the Japanese fought and really helped unify this country. Anyone interested in the legacy of the samurai should definitely look into Morishige-ryu for some substantial information on Japan’s real “arts of war”; “real” because like tameshigiri (live blade target-cutting) and archery, the whole experience is a realization that every time you use these weapons, you do it to kill someone –no matter how you idealize it, this is a truth that you have to live with, even if you’re just shooting circles on a piece of paper.

The author shooting a long hinawaju…

…and a short tanju

One last thing: I would be hard-pressed to find what was more enjoyable in this experience. Yes, the theoretical knowledge was enough to fill a small book and the actual handling of the weapons was challenging in obvious and less obvious ways (try holding a 3-5kg/6,5-11lb gun straight even without shooting: it’s much harder than you think) but I think the part I’ll remember most fondly will be the attitude of Shimazu, Uchi and Nagatsuka-sensei and Nishiyama-san. And I don’t mean the mandatory politeness that everyone (and even more so, everyone in Japan) shows to media people writing about them. I mean the true openheartedness they showed us, really enjoying showing us the different arts that come together to create their Morishige-ryu. Having been around soldiers, I can tell that this balance between levity and gravity, between seriousness and playfulness, between discipline and uninhibitedness is a true mark of someone who understands life and death –if I haven’t completely misunderstood Japan and its martial arts, this is the true legacy of the samurai.

──The Hiden Budo and Bujutsu Magazine,

JUNE 2018

About the author

About the author

Grigoris Miliaresis has been practicing Japanese martial arts since 1986. He has dan grades in judo, aikido and iaido and has translated in Greek over 30 martial arts’ books including Jigoro Kano’s “Kodokan Judo”, Yagyu Munenori’s “The Life-Giving Sword”, Miyamoto Musashi’s “Book of Five Rings”, Takuan Shoho’s “The Unfettered Mind” and Donn Draeger’s “Martial Arts and Ways of Japan” trilogy. Since 2007 his practice has been exclusively in classic schools: Tenshin Buko-ryu Heiho under Ellis Amdur in Greece and Kent Sorensen in Japan and, since 2016, Ono-ha Itto-ryu under 17th headmaster Sasamori Takemi and 18th headmaster Yabuki Yuji.

http://about.me/grigorismiliaresis