Waterfalls, autumn leaves, tengu and sharp swords

Text and Photo by Grigoris A.Miliaresis

Act I: A warm day in the Meiji Jingu

“I’ll be in your neck of the woods in a couple of weeks” said the message on Facebook from my Greek friend, Vassilis; this was great news since I hadn’t seen him for quite a while and it’s always nice spending time with him. Vassilis is almost 15 years younger than me but he has done quite enough budo for his age: he was among the first people who did kendo and iaido in Greece about 13 years ago and he has been a member of the Athens Aikido Society, the Greek dojo of Shiseikan Budo for the last 11. He is now a kendo and iaido 3rd dan, and an aikido 2nd dan and if those sound low, please keep in mind that kendo and iaido are less than 15 years old, that the top-level Greek teachers are a 5thdan in kendo, a 5th dan in iaido and a 4th dan in jodo and that there are less than 250 people practicing these arts –together!

Seeing Vassilis again –and especially in Tokyo- was great but what intrigued me most was that he would be coming to Japan for a special training event organized by the Shiseikan: select members of the organization (mostly group leaders or senior practitioners) from all over the world would come to Japan, stay for ten days, train on a daily basis at the wonderful Shiseikan dojo in the grounds of the Meiji Jingu and part of their training would be visiting Mt. Mitake in the Chichibu Tama Kai National Park, north of Tokyo and participating in a misogi purification ritual under a waterfall at the crack of dawn. Since I hadn’t seen an actual misogi ritual, I thought it would be a perfect opportunity so I had to take the chance: arrangements were made and a few hours before the group left for Mt. Mitake we found ourselves in one of the rooms in the Shiseikan listening Araya Takashi, the present director of Shiseikan explain to the members what it was that they would be doing up in the mountains.

To be honest I didn’t know much about Shiseikan and its teachers; I mostly knew of Inaba Minoru, student of Kashima Shinryu’s Kunii Zenya and Aikido’s Ueshiba Morihei, teacher of both in the Shiseikan since its opening in 1973, previous director of the dojo and the organization and a strong supporter of the idea that budo practice can’t be separated from study of Shinto, Japan’s native religion. This was the first time I met Araya sensei though and the context was really interesting –in an odd way: here was a man whose military background clearly showed (Araya sensei was a career officer and founder and first commander of the Special Forces branch of the Japan Self-Defense Forces but he left the army in 2007 to become the third director of Shiseikan) explaining to a group of 20 plus foreigners what is misogi in general and how they will be performing their misogi in particular using a whiteboard and colored markers.

The explanation included a description of the concept of misogi (i.e. a process of cleansing the body and mind) as well as specific information about the various steps the practitioners would follow during their misogi which was to be led by Araya sensei himself. The steps were haraikotoba (the verbal expression of the will to get purified), torifune (the rowing exercise well known to everyone who has done aikido accompanied by several ritual phrases), otakebi (or sowing the seeds of will), okorobi (the kami’s reply to the practitioner’s call), ibuki (the breathing providing the inner preparation) and the actual misogi, the stepping under the waterfall. “Don’t antagonize the water or the cold” was Araya sensei’s advice to the practitioners “They are nature and nature is enormously powerful –no one can antagonize it. Embrace it and let it engulf you so you’ll become one with it; that way its power becomes yours and this can make you formidable in a budo context”. Shamanistic? Certainly –Shinto is, after all, animistic.

As Araya sensei was talking and explaining I took the opportunity to observe the members’ reactions. They were all polite and quite of course but it was obvious from the look in their eyes that for some of them the prospect seemed somewhat unnerving; as I would find out later those were the people who hadn’t done this before or those who had but not in a waterfall in the winter but in the sea and during summer (without wanting to trivialize it, knowing what “summer” means in Japan, a dip in the water falls less under the category of “misogi” and more under the category “relief”!) Even though Araya sensei’s explanations were done in normal, everyday language, a rather soft tone and without any mystical overtones other than the ones inherent to a, basically, religious practice there seemed to be a sense of uneasiness lingering in the room. Perhaps it was his authoritative demeanor, something I’ve often seen in people with an army background.

Act II: A cold evening on Mt. Mitake

We would be staying the night at a minshuku (sort of like a bed & breakfast) but we wouldn’t be having dinner so we stopped at a convenience store and got a few things; one of them had to be hot soup or cap-men since the cold was considerable. We returned to the car (my Japanese colleague was driving) and while drinking some hot tea we entered Mitake mountain –“entered” is literal here since a tori gate marks the entrance leaving no doubt that for Shinto this was a holy mountain. Saddling four prefectures (Yamanashi, Saitama, Nagano and Tokyo) what it lacks in size (not that its 929 meters aren’t impressive) makes up for in steepness. Also, as we were going to find out, in enormous cryptomerias, great vistas especially in the autumn leaves season called “koyo” and, apparently, in tengu –the long nosed or craw-headed mountain goblins well known for their relationship with budo.

Going up the first 400 or so meters was easy –the 5-minute cable car of Mitake Tozan took care of them. The second 300, not so much: going from the cable car station to the minshuku was not exactly an invigorating evening stroll. It was dark, cold, fog was starting to form, there wasn’t a soul to be seen and even though visibility was very limited you could sense that there was an abyss gaping at the edge of the narrow path. And it was steep –but not as steep as the second part, the other 300 meters from the minshuku to the Musashi-Mitake Shrine where we were invited to watch the evening kagura dance, together with the Shiseikan members who had arrived separately. The shrine’s kagura is a tradition going well into the Edo period and, unlike other similar performances there is a variation (which we were fortunate to watch) were dancers wear Noh theater masks. As for the main play it was appropriate for the crowd of budoka comprising a good part of the audience: it was the legend of the eight-headed dragon Yamata-no-Orochi and its epic fight with the sea-and-storm god Takehaya Susanoo-no-Mikoto.

Exiting the shrine after the kagura we were surrounded by statues of dogs representing Musashi-Mitake’s main deity, “O-Inu-sama”, the white wolf that guided legendary 1st-2nd century prince Yamato Takeru when he got lost in the mountain and darkness broken only by the torches lit in front of the shrine’s main structure and a spotlight illuminating the statue of Shigetada Hatakeyama, one of the heroes of the Gennpei War. We walked down the road to the minshuku chatting with Vassilis about how the stances of Yamata-no-Orochi and Takehaya Susanoo-no-Mikoto during the dance-fight with sword and spear could be interpreted as kamae fighting stances of the martial arts. The silence was eerie and the atmosphere filled with anticipation for the next morning’s misogi; we left the Siseikan members to their minshuku and headed towards ours for dinner and a peaceful sleep with the kerosene stove lit. You don’t want to mess with the weather in the mountains.

Act III: The light of a new day

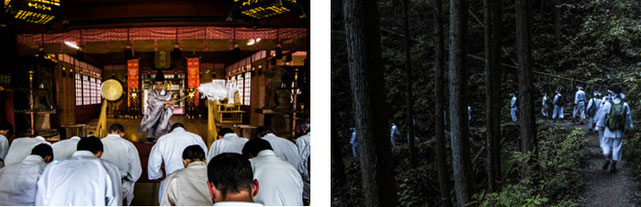

We arrived at the Shiseikan members’ minshuku at the time when the priest from the shrine was offering them a final blessing before their misogi: everyone was dressed in white keikogi and a white hachimaki headband making them look like pilgrims (which, in essence they were). The ceremony was short and as soon as it was over, Araya sensei and his assistants (presumably, senior Shiseikan members) gave members their last instructions for the beginning of the hike to the Ayahiro waterfall passing first once again from the Musashi-Mitake Shrine –climbing up the stairs to the shrine was the warming-up for the 1,5 hour walk that was going to follow.

It was a little after 6:00 and the sun was just coming up as the members, walking in a single line made their way through the trees and the ascending and descending path towards the waterfall, passing from places with names like “Tengu Rock” and “Rock Garden” –the long-nosed mountain goblins were a part of Mt. Mitake’s lore since time immemorial and considering our group’s relation to the martial arts it seemed appropriate: since the times of Minamoto no Yoshitsune, the tengu were thought of as patrons and teachers of martial arts so if you are a martial artist participating in a ritual that brings you in touch with nature, doing it at a place where tengu reigned, sort of guarantees your success. And if the ritual is done properly and honestly, perhaps the tengu will share some of their wisdom like Sojobo did with the young Genji warrior in Mt.Kurama.

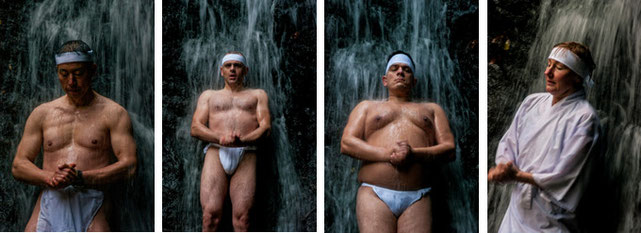

Night turned into day as we reached the waterfall; I would like to say that I enjoyed the hike but the pace was too fast to actually see anything and you could tell that no one was paying much attention to the splendid landscapes unfolding as darkness gave way to light, with the autumn leaves changing from deep green to crimson and yellow. Having served in the army myself I could well understand why Araya sensei didn’t allow any slack until the group reached the waterfall: he wanted his “troops” well warmed up so they would be better prepared to enter the cold water. And the trick worked since upon arrival to the Ayahiro waterfall everyone promptly stripped down to their white fundoshi (the traditional Japanese underwear –for men: the women in the group wore a long white tunic) and followed sensei to a rock plateau a couple of meters in front of the water. Following sensei’s lead they engaged in the rituals explained the previous day in the Meiji Jingu (which seemed so very far away both in time and in space) with their kiai and incantations echoing in the valley. And after that, one by one, they entered the water.

I didn’t do the misogi so I can’t speak about it; I’d rather convey here what the Shiseikan members told me. “It’s something you need to do. You understand –better yet, feel- that everything makes sense”; “I often feel my body does what it wants but at the same time I feel that deep inside me there is a different self, an original self that wants to awaken. This is the part of me that came up with misogi”; “I feel clean, rejuvenated; before you had questions but after doing it you feel you have the answers”; “You understand better who you are so your budo becomes better”; “The hike until there was a preparation: walking through nature raised my awareness and it all made sense at the moment my bare back touched the rock and the first drop hit my body”; “You come in contact with a deeper part of Japan”; “It was a challenge: at first I was afraid about my health but surviving it makes me better prepared for the next challenge”.

Those were the words of Pavel and Vadim from Russia (33), Daniel, also from Russia (25), Anthony from Poland (41), Maximilian, also from Poland (45), Lee from England (44) and Mirjam from Germany (47). As for Vassilis, he felt more open and clean, better equipped to function in the world and a with a deeper understanding of how one should face adversities: by breathing naturally and allowing yourself to become one with the adverse situation –you open (and thus, overcome) yourself to the situation and instead of opposing it you understand how to make it work to your benefit. In misogi you learn that through coming across the mightiest “opponent” of all i.e. nature itself.

Act IV: A cloudy morning at the Meiji Jingu

It was five days later and we were once again at the Shiseikan dojo to watch the group’s last day of training before the seminar was over and they returned to their countries. The lesson was iai but performed with shinken i.e. live blades and for me it made perfect sense: after having looked deep inside you with misogi and after several days of stern training, your final lesson should be with the weapon epitomizing Japanese budo and everything Shiseikan and its art stands for, the real Japanese sword. It was a typical class: Araya sensei demonstrated the kata and then the members performed them in groups (for safety reasons and because there were only a few shinken they could use –since bringing a live blade in Japan can result in some very bothersome interactions with customs, the members used Shiseikan’s own swords) while sensei and his senior students went around explaining details, answering questions and making corrections.

I noticed something interesting though: the members’ experience in the art varied –from four years to over fifteen- and it was pretty obvious that some of them hadn’t trained much with a shinken. Still, they all managed to handle the sword properly and in the three hours the class lasted there was not even the slightest injury even though after a while they were all moving quite fast. It seemed that Araya sensei’s introduction in the beginning of class, where he likened the practice to misogi and advised the practitioners to treat the sword in the same way they treated the waterfall that morning in Mt. Mitake had aroused something strong inside their minds and bodies and their delivery was, if not perfect, at least very good. If only for that, and for its implications both in training and in life, I would think that this whole experience was worth it.

The members thought so too: In our discussion after their class, every single one of them had only positive things to say about this trip and about what they’d be bringing back home; also, every single one of them confirmed that they’d do it again if given the opportunity (there was one though who emphasized that especially the misogi shouldn’t be done very often because it will lose its significance and become routine; a good point, I think). From their words it was clear that these ten days had offered them a better understanding of the profound connection between martial arts and native Japanese spirituality and of mind, body and spirit, of the essence of the techniques they practice in the dojo and of the extensions of all the above in everyday life. If the Shiseikan founders’ wish was keeping the values of martial arts alive and relevant to the modern world and to disseminating them in Japan and the world, it seems to me that this seminar was a very successful step towards this direction.

About the author

About the author

Grigoris Miliaresis has been practicing Japanese martial arts since 1986. He has dan grades in judo, aikido and iaido and has translated in Greek over 30 martial arts’ books including Jigoro Kano’s “Kodokan Judo”, Yagyu Munenori’s “The Life-Giving Sword”, Miyamoto Musashi’s “Book of Five Rings”, Takuan Shoho’s “The Unfettered Mind” and Donn Draeger’s “Martial Arts and Ways of Japan” trilogy. Since 2007 his practice has been exclusively in classic schools: Tenshin Buko-ryu Heiho under Ellis Amdur in Greece and Kent Sorensen in Japan and, since 2016, Ono-ha Itto-ryu under 17th headmaster Sasamori Takemi and 18th headmaster Yabuki Yuji.

http://about.me/grigorismiliaresis