text and photo by Grigoris Miliaresis

Cliche exist because they serve a purpose: when writers select their tools, there are times when they reach for the obvious because, well, only the obvious will do. Tennen Rishin-ryu’s relationship with Shinsengumi, the Bakumatsu-era special police force patrolling the streets of Kyoto, is so well-known even to people not involved with classic martial traditions that it can’t be ignored –even here, in “Hiden” we included this installment of our “experiencing a koryu” series focusing on this school in a feature about the Shinsengumi. But I want to make it clear up front: having a chance to be introduced in Tennen Rishin-ryu and especially as taught in Kato Kyoji’s Bujutsu Hozonkai dojo has been a five-year old wish come true.

Tennen Rishin-ryu and me

Kato Kyoji and Sandro Furzi

The reason? They are two, actually. The first is that since I came to Japan I developed a deeper interest in (and, I’m not shamed to admit it, a deeper respect for) kendo and its roots. “Hiden” readers know that I’m practicing Ono-ha Itto-ryu at Reigakudo and Itto-ryu’s relationship with kendo is well-known so having a chance to see from up close a school focusing on gekiken, kendo’s more recent ancestor is something I’ve wished for a long time. And even more so (and this is the second reason), since I met Sandro Furzi from Italy, one of Kato sensei’s older students and was introduced to his teacher.

You see, this visit at the Bujutsu Hozonkai dojo wasn’t my first contact with Mr. Furzi and Kato sensei: I had met the former socially and was instantly charmed by his demeanor, character and dedication to Japan’s culture and through him I had been invited, back in 2016, when they started their dojo, not only to watch their practice but also participate if I wanted. I did watch (personally, not with “Hiden”) and was in turn charmed by Kato sensei’s warmth, joyfulness and deep love for the tradition he has been studying and teaching. Being a martial arts’ professional (of sorts!) I’ve had the opportunity to meet hundreds of martial artists and I can honestly say that Kato sensei and Mr. Furzi are easily in the Top-10!

Grigoris Miliaresis putting on the kendo bogu

So doing a Tennen Rishin-ryu “experience” article was inevitable for both personal and, well, historical reasons. And now, as I write about our visit I can say it was undoubtedly worth it! Not only I had the opportunity to put on again my kendo bogu after over ten years, but also to practice in a way very different from present-day tournament-oriented kendo involving, by Tennen Rishin-ryu practitioners’ estimates, 70% sword techniques (using the school’s trademark extra thick and heavy bokuto, regular bokuto and shinai) and 30% unarmed techniques, most of them while in armor! Because, and this is what many don’t realize about gekiken, in its context you can’t practice the one without the other: you go from long distance to short distance to body collision to standing grappling to ground grappling as would happen in a real fight.

Tennen Rishin-ryu’s trademark extra-thick and heavy bokuto

The history -and Shinsengumi (of course)

Kondo Isami (1834-1868)

First let’s get the Shinsengumi connection out of the way: Tennen Rishin-ryu was created by Kondo Kuranosuke Nagahiro in the late 1700s after a musha-shugyo (quest for knowledge) around the country which included study of Kashima Shinto-ryu. Kuranosuke had to take into account the demands of late Edo-period people for a swordsmanship style that allowed safe competition between different schools by the use of some rules and some protective equipment (i.e. gekiken, i.e. kendo). He was active in Edo and Kanagawa and during the times of his third successor Kondo Shusuke (1792-1867) and Shusuke’s adopted son, Kondo Isami (1834-1868) the school became quite famous. Kondo Isami, becoming commander of the Shinsengumi and other three of its thirteen core members (Hijikata Toshizo, Okita Soji and Inoue Genzaburo) also practicing the school certainly added to its fame.

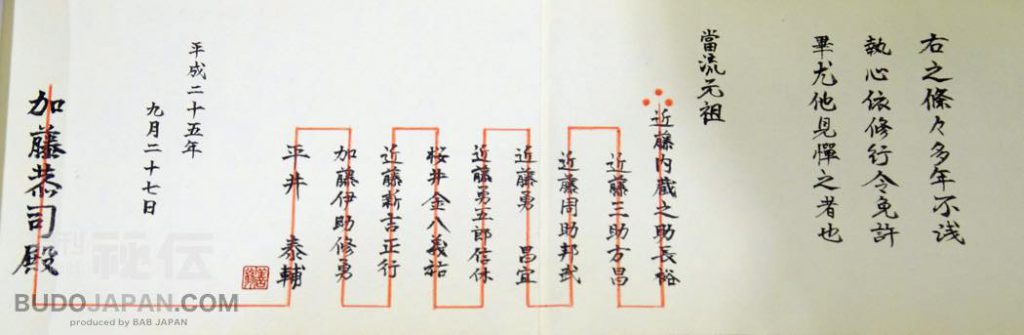

Tennen Rishin-ryu Menkyo

Shinsengumi didn’t survive the Meiji restoration and neither did Kondo, Hijikata, Okita or Inoue. But thanks to the school’s popularity several Tennen Rishin-ryu teachers kept it alive in the broader Edo/Tokyo area and through Kondo Isami’s adopted son, Yugoro and his dojo in Chofu, Hatsuunkan, it was transmitted during Taisho, Showa and Heisei periods and up to the time of Hirai Tasuke, teacher of both Kato sensei and Mr. Furzi. And to anticipate the standard question “How much of the Shinsengumi times’ Tennen Rishin-ryu is Bujutsu Hozonkai teaching today?” the answer is “Who can really tell?” And that doesn’t only apply to Tennen Rishin-ryu: I couldn’t answer that even for the two traditions I am studying but I trust my teachers and their teachers that they did their best to keep alive their essence. And I’m certain Kato sensei does too!

Moving on to gekiken -and staying there

Bokuto-no-kirikaeshi

We started our practice at the Bujutsu Hozonkai with bokuto-no-kirikaeshi, a warm-up exercise where partners run towards each other doing kiai, strike three times at men level and retreat. It sounds easy but doing it with Tennen Rishin-ryu’s 100cm/3’2” long, 6cm/2.3” thick and 2kg/4.5lbs heavy bokuto and with kiai coming and going makes it quite exhausting –which is exactly the purpose! From there on, we moved to the first kata of the school’s Kenjutsu Omote, called “Jochuken”, again performed with the big bokuto. In Jochuken, shitachi in seigan approaches uchitachi who is in jodan, they attempt a mutual men cut, disengage and return for a second mutual men; this time shitachi pushes uchitachi who retreats to jodan and shitachi closes the distance and finishes with a solar plexus thrust. This is classic kenjutsu but like the warm-up, the extra-heavy, extra-thick bokuto makes it quite challenging!

Kenjutsu Omote “Jochuken”

The next thing we did before wearing the bogu (which, incidentally in Tennen Rishin-ryu also includes under-hakama shin protectors: shins are also targets) was “Yokozuki” from Mokuroku’s “Kogusoku” section. Here, shitachi blocks with his kodachi uchitachi’s sword and then grabs both uchitachi’s arms and brings him down illustrating how natural is the passage from armed to unarmed techniques. Kato sensei was kind enough to demonstrate several variations to what follows the take-down, explaining that during free sparring, practitioners are encouraged to use whatever feels appropriate each time.

“Yokozuki” from Mokuroku’s “Kogusoku”

Practice continued with various techniques from different parts of Tennen Rishin-ryu’s curriculum: First from Kirigami (first level) were “Sen-no-koto” (men strike from jodan), “O-no-koto” (deflecting a men strike), “Shiaiguchi” (a sequence of mune tsuki, three kendo-style kirikaeshi, another mune tsuki and a final mune tsuki from jodan) and “Soi-kirikaeshi” (kendo kirikaeshi but with ayumiashi footwork); as is obvious, in Tennen Rishin-ryu tsuki isn’t limited to the throat like in kendo but can also target mune and the face –and the latter can be really nasty!

Kao tsuki

Mune Tsuki

Leg strike

Then, from Chugokui Mokuroku followed “Oken” (uchitachi strikes at shitachi’s left kote when he’s in jodan; shitachi lets go of the left hand and strikes men with the right),

Oken 1

Oken 2

Oken 3

“Hienken” (both are in jodan, shitachi deflects uchitachi’s men and strikes do while stepping out of range -and possibly kneeling)

Hienken 1

Hienken 2

Hienken 3

“Muitsuken” with shitachi holding the blade part of the shinai, in mugamae (regular stance with the shinai held horizontally in the front) from where he uses it to block a men attack either directly from the front or moving to the side, hitting uchitachi’s wrist and following with a powerful jukendo-style two-handed tsuki to the face or blocking and then grabbing both uchitachi’s arms in his armpit like the technique used in Yokozuki with the kodachi

Muitsuken 1

Muitsuken 2

Muitsuken 3

Muitsuken 4

Muitsuken 5

Muitsuken 6

and “Ten-chi-jin” where shitachi also holds the shinai with his two hands but in naname-no-gedan kamae –this is a side stance where shitachi tries to hide the shinai and at some point whips it like an arrow towards uchitachi’s inner kote or face.

Ten-chi-jin 1

Ten-chi-jin 2

The final technique, Otaiken, came from Menkyo and it was a more realistic reaction to kendo’s tsuba-zeriai: shitachi pushes uchitachi’s kote away and strikes men with the other hand while pulling back –simple and extremely effective!

Otaiken 1

Otaiken 2

Otaiken 3

Ken-Tai-Ichi revisited

Because of a left shoulder pinched nerve, I thought I’d stay away from the unarmed techniques; 15 minutes in the practice, after the heavy bokuto kata, I realized that in Tennen Rishin-ryu this is impossible. As I wrote before, their curriculum is 70% sword/30% taijutsu and passing from the one to the other is so smooth and natural that either as a viewer or as a practitioner you can’t see or feel the seams: if your body placement allows you to use your sword you use it –if not, you use your body and you do it in the most effective way. When at some point we asked Kato sensei about a hip throw, he said that while wearing armor (real bushi armor or kendo bogu), a hip throw would be hard –kneeling down and having the opponent tipped over would be more realistic. And when he demonstrated it on Mr. Furzi, it really was.

Gekiken grappling 1

Gekiken grappling 2

Pushing the opponent to the wall

The Shinsengumi captains’ famed fighting skills notwithstanding, there’s little doubt that Tennen Rishin-ryu’s techniques were created in an era where the shinai was much more in use than the real sword. Edo in the end of the Tokugawa bakufu was a hotbed for shiai-kenjutsu and for reinventing the training and practicing paradigm through various combinations of kata and free practice leading to the creation of hundreds of new dojo, especially in the cities and dozens of “New Ryu” created by samurai and commoners alike, all exploring and developing what would become today’s kendo. Kato sensei’s Tennen Rishin-ryu (incidentally there are other lineages, but not having visited them I can’t speak about their interpretation) is true to that spirit and its kendo shows its roots with its throws, expanded target areas and “unorthodox” techniques like using the opponent’s do or men to choke him. Interestingly, the school’s curriculum also includes 12 iai kata, nine in seiza and three standing –quoting Mr. Furzi, “they are simple applications/basic sword drawing actions that people carrying swords were supposed to know.”

Gekiken grappling 3

Gekiken grappling 4

Bujutsu Hozonkai

There’s a phrase going around martial arts’ circles: most people come to the dojo because of self-defense but most stay for any other reason than self defense; paraphrasing this, perhaps most people are drawn to Tennen Rishin-ryu because of Shinsengumi but most of them should stay for any other reason. Tennen Rishin-ryu might be younger than some extant schools but certainly doesn’t lack depth or sophistication. It has a very realistic, well-rounded curriculum within the assumptions/restrictions/parameters of the Bakumatsu era (and probably of those immediately following it) and I have no doubt that its practitioners would have been able to hold their own even at those times of heavy inter-school competition; I won’t even mention today since many schools don’t practice realistically anymore.

Gekiken Shiai 1, tsuki

Kato sensei’s teaching methodology is also indicative of the importance of reality-based practice (i.e. gekiken) in Tennen Rishin-ryu: students are introduced to various techniques from the school’s curriculum not in sequence as usually happens but through gekiken; this way they can learn them as they would work with shinai and bogu and when time comes to perform them in the kata with bokuto, not only they already know them but they know their functionality and applications. This knowledge informs their kata and imbues them a vitality that sadly many schools lack.

Gekiken Shiai2, grappling

Gekiken Shiai 3, grappling on the ground

In closing, I would like to say with absolute sincerity (and with enough years in journalism to be able to keep my personal feelings aside) that if I’d come across Tennen Rishin-ryu as Bujutsu Hozonkai practices it even 20 years ago, I probably wouldn’t have searched any further. It has a very well-balanced combination of kata and free practice, weapons’ work and empty-hand work and historically it is old enough to be a koryu but young enough to be influenced by the big-city culture of later-day Edo which I find fascinating. Furthermore, the dojo’s approach (credited to Kato sensei and his understanding of budo but I’m sure with Mr. Furzi’s input too!) is conducive to more evolution and development in the way these traditions should be; by “approach” I mean as much the knowledge and the understanding as the atmosphere and the mood. Kato Kyoji’s Tennen Rishin-ryu isn’t just “the school of the Shinsengumi” and it isn’t just the legacy of Kondo Isami: it’s much, much more.

Kato Kyoji’s Bujutsu Hozonkai

PS

As always, I owe a combination of gratitude and apology, first to Kato Kyoji sensei and Mr. Sandro Furzi for being such perfect hosts and second to Bujutsu Hozonkai students for upsetting their practice and keeping their instructors busy. Please, accept this brief account of our day in your dojo as a consolation prize.

About the author

About the author

Grigoris Miliaresis has been practicing Japanese martial arts since 1986. He has dan grades in judo, aikido and iaido and has translated in Greek over 30 martial arts’ books including Jigoro Kano’s “Kodokan Judo”, Yagyu Munenori’s “The Life-Giving Sword”, Miyamoto Musashi’s “Book of Five Rings”, Takuan Shoho’s “The Unfettered Mind” and Donn Draeger’s “Martial Arts and Ways of Japan” trilogy. Since 2007 his practice has been exclusively in classic schools: Tenshin Buko-ryu Heiho under Ellis Amdur in Greece and Kent Sorensen in Japan and, since 2016, Ono-ha Itto-ryu under 17th headmaster Sasamori Takemi and 18th headmaster Yabuki Yuji.

http://about.me/grigorismiliaresis