text by Grigoris Miliaresis

photo by Grigoris Miliaresis

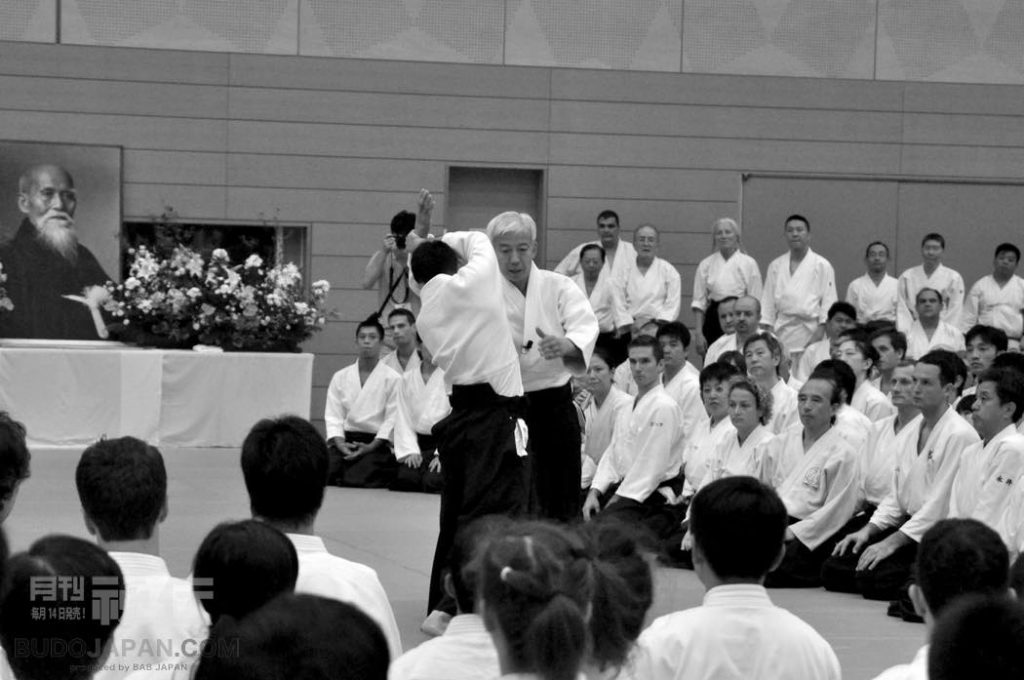

At a certain point, during his free technique demonstration towards the end of his class the Doshu said to his uke “Hey, look –we don’t want to knock out that guy with the camera”. And that’s when it hit me: the guy with the camera was me, sitting in the front line of a crowd easily one thousand strong and less than ten feet from the man who is the head of the Aikikai Foundation and the carrier of the aikido founder’s legacy; both in a literal and a figurative sense. I was on Ueshiba Moriteru’s tatami with the permission to take as many pictures as I wanted and watch his class from a distance that most aikidoka around the world only dream of. Yes, there are times like this when I honestly love my job!

photo by Grigoris Miliaresis

Of course I have seen the Doshu before, in his regular class in the Aikikai Honbu. And in a sense, his class at the last day of the seminar running parallel to the International Aikido Federation’s 11th International Aikido Congress in Yoyogi’s National Olympic Memorial Youth Center wasn’t that different. But that is to be expected: he is the Aikido Doshu so he needs to provide the standard against which all aikidoka measure themselves –and in a martial art as diverse and as multifaceted as aikido this is really hard, making his job all the more difficult. Still, he manages to be the perfect embodiment of true aikido: starting from the square of the hanmi kamae, the triangle of irimi was blending with the circle of tenkan giving birth to all the techniques that his grandfather inherited from Daito Ryu and transformed in his head to create this truly unique martial art.

photo by Grigoris Miliaresis

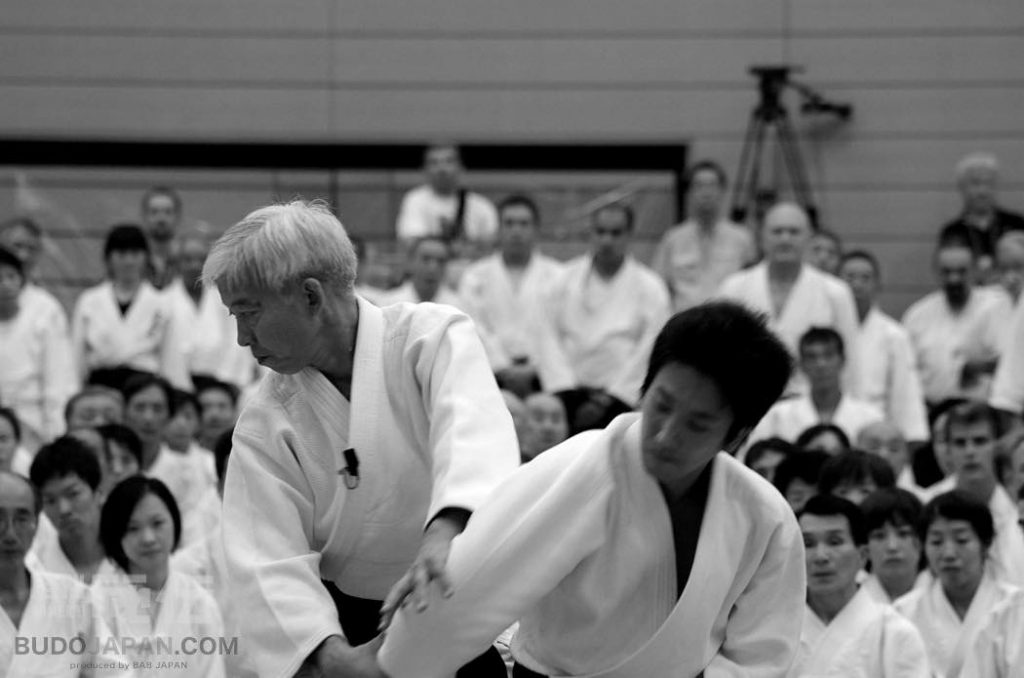

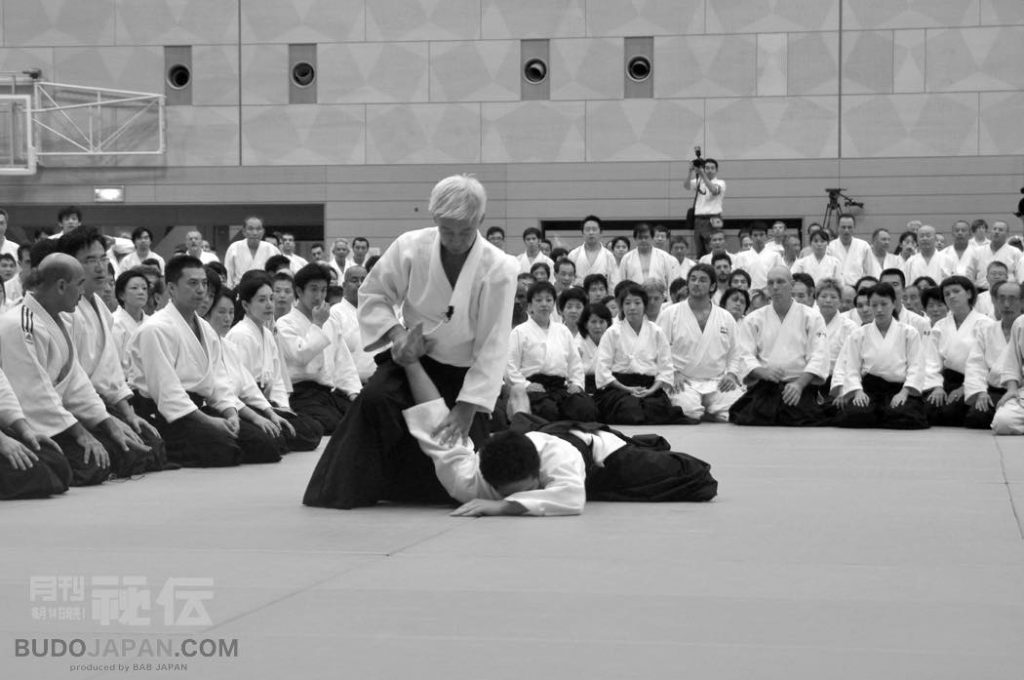

It has been years since I really trained in aikido (I’m not counting the occasional seminar) but the atmosphere on the Youth Center’s tatami really had me itching to put down my cameras and my notepad, don my keikogi and hakama and jump right in. And it wasn’t just because of the Doshu’s steady rhythm that went on unwaveringly for the 1,5 hour that the class lasted. It was also because of the hundreds of aikidoka of all ages and body types and levels from 33 countries who filled the tatami trying to duplicate his technique as best as they could; if, judging from his videos, you think that this would be easy think again! Like most people who are good at something, Moriteru Doshu makes his thing (i.e. aikido) seem deceptively simple. But the subtlety is there –it’s just hidden. In plain sight.

It has been years since I really trained in aikido (I’m not counting the occasional seminar) but the atmosphere on the Youth Center’s tatami really had me itching to put down my cameras and my notepad, don my keikogi and hakama and jump right in. And it wasn’t just because of the Doshu’s steady rhythm that went on unwaveringly for the 1,5 hour that the class lasted. It was also because of the hundreds of aikidoka of all ages and body types and levels from 33 countries who filled the tatami trying to duplicate his technique as best as they could; if, judging from his videos, you think that this would be easy think again! Like most people who are good at something, Moriteru Doshu makes his thing (i.e. aikido) seem deceptively simple. But the subtlety is there –it’s just hidden. In plain sight.

In this respect the Doshu resembles his father and his grandfather; OK, maybe not so much his grandfather since at least his talk while teaching is straightforward. In the IAC’s class he only emphasized tai sabaki (as irimi or tenkan) and kokyu and demonstrated how these can lead to an ikkyo, a nikyo, a kote gaeshi or a shiho nage either from standing position of from hanmi handachi –all clear, crisp and with the ease of someone who has been doing this long enough to know exactly when to move, where to step and how to keep himself covered (i.e. without any openings). Furthermore, he always gave out the air that he knew what is important and what not; something that is not always the case even with top level instructors –in aikido and in other martial arts.

In this respect the Doshu resembles his father and his grandfather; OK, maybe not so much his grandfather since at least his talk while teaching is straightforward. In the IAC’s class he only emphasized tai sabaki (as irimi or tenkan) and kokyu and demonstrated how these can lead to an ikkyo, a nikyo, a kote gaeshi or a shiho nage either from standing position of from hanmi handachi –all clear, crisp and with the ease of someone who has been doing this long enough to know exactly when to move, where to step and how to keep himself covered (i.e. without any openings). Furthermore, he always gave out the air that he knew what is important and what not; something that is not always the case even with top level instructors –in aikido and in other martial arts.

photo by Grigoris Miliaresis

The two characters reading “Usehiba” on his hakama make it easy to attribute his ease to being who he is and forget that this is a man who has been doing aikido for fifty five years, always in the Honbu Dojo and always under the supervision of the greatest teachers the art had to offer. One can easily assume that this name (and the legacy that goes with it) certainly helped him get some preferential treatment from the teachers of that age –most prevalent among whom was, well, his father- and that with the dojo being his home, things might have been easier for him than to other students of aikido, even in Japan. Even if this is true, though, it doesn’t negate the fact that even a casual observer will immediately understand: that this man has put in the hours needed to become a top-caliber aikido practitioner and instructor.

And the seminar participants certainly felt it! In all the conversations I managed to squeeze in before, after or during his class all the aikidoka regardless of their level or their country of origin readily admitted that Doshu’s aikido is the perfect illustration of the Aikikai style (or, to be more accurate, to the mixture of styles starting from Ueshiba Morihei and being carried down to his first and second generation students). “His style is exactly what aikido is all about” said a practitioner from Brazil “flowing techniques executed in perfect timing”. “I love that what he does is no-nonsense” was the comment from an American practitioner living and training in Japan “These days you see a lot of things in aikido that don’t make sense but Moriteru Doshu’s aikido certainly doesn’t fall into this category. It works.” “He is great! This is the first time I train on the same tatami with him and I even had the opportunity to take ukemi for him –you can really feel the power of his technique but at the same time it is gentle” were the words of a Chinese aikidoka who came to Japan for the first time and who has been training in Beijing for four years.

And the seminar participants certainly felt it! In all the conversations I managed to squeeze in before, after or during his class all the aikidoka regardless of their level or their country of origin readily admitted that Doshu’s aikido is the perfect illustration of the Aikikai style (or, to be more accurate, to the mixture of styles starting from Ueshiba Morihei and being carried down to his first and second generation students). “His style is exactly what aikido is all about” said a practitioner from Brazil “flowing techniques executed in perfect timing”. “I love that what he does is no-nonsense” was the comment from an American practitioner living and training in Japan “These days you see a lot of things in aikido that don’t make sense but Moriteru Doshu’s aikido certainly doesn’t fall into this category. It works.” “He is great! This is the first time I train on the same tatami with him and I even had the opportunity to take ukemi for him –you can really feel the power of his technique but at the same time it is gentle” were the words of a Chinese aikidoka who came to Japan for the first time and who has been training in Beijing for four years.

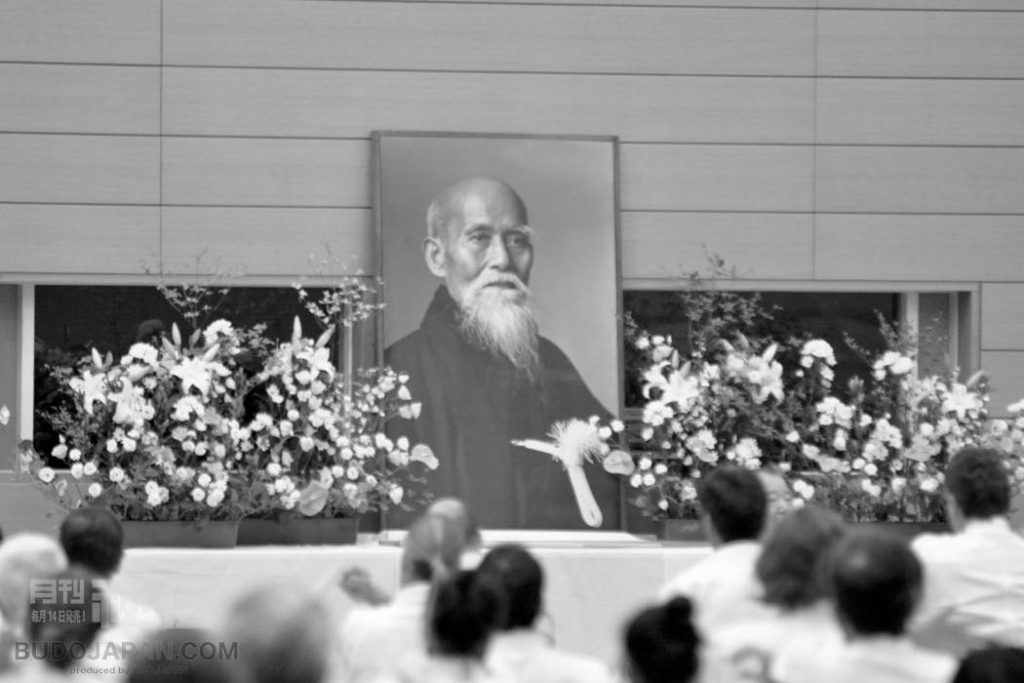

Everybody finished the Doshu’s class smiling; the difficulty of doing aikido in such a limited space (limited because of the numbers of the attendees; not because of actual lack of space) didn’t stop everyone from having a good time and learning things that will help them make their training better. And the most important among these things is that everybody got the chance to train on the same mat with people from all over the world under the eye and the guidance of a teacher sharing the actual as well as the “artistic” genes of the man who created aikido –in the big picture of Ueshiba Morihei featured in the dojo kamiza, everybody saw the founder of their chosen art but Ueshiba Doshu saw something more: a beloved family figure the perpetuation of whose dream has been the destiny and the purpose of his life.

Everybody finished the Doshu’s class smiling; the difficulty of doing aikido in such a limited space (limited because of the numbers of the attendees; not because of actual lack of space) didn’t stop everyone from having a good time and learning things that will help them make their training better. And the most important among these things is that everybody got the chance to train on the same mat with people from all over the world under the eye and the guidance of a teacher sharing the actual as well as the “artistic” genes of the man who created aikido –in the big picture of Ueshiba Morihei featured in the dojo kamiza, everybody saw the founder of their chosen art but Ueshiba Doshu saw something more: a beloved family figure the perpetuation of whose dream has been the destiny and the purpose of his life.

photo by Grigoris Miliaresis

Closing this brief account of the Doshu’s class in the 11th International Aikido Congress I need to comment on something that really grabbed my attention and made me thinking. Even though everybody shared a feeling of gratitude for being there and sharing a tatami with the head of the Aikikai, most fortunate among the participants were two that probably had the least comprehension of their fortune: they were two little girls (probably elementary school age) one white and one black practicing in the shimoza side of the tatami, obviously for safety reasons. They were very earnest in their training and tried as best as they could to execute the techniques the way the Doshu taught them in the laconic and concise style that characterizes most Japanese teachers. I don’t think that their age allowed them to understand the significance of the man teaching the class, but if they continue training in aikido, there will come a day that they will be able to say “I trained with the Third Doshu when I was seven or eight years old” –how many among us can say that?

About the author

About the author

Grigoris Miliaresis has been practicing Japanese martial arts since 1986. He has dan grades in judo, aikido and iaido and has translated in Greek over 30 martial arts’ books including Jigoro Kano’s “Kodokan Judo”, Yagyu Munenori’s “The Life-Giving Sword”, Miyamoto Musashi’s “Book of Five Rings”, Takuan Shoho’s “The Unfettered Mind” and Donn Draeger’s “Martial Arts and Ways of Japan” trilogy. Since 2007 his practice has been exclusively in classic schools: Tenshin Buko-ryu Heiho under Ellis Amdur in Greece and Kent Sorensen in Japan and, since 2016, Ono-ha Itto-ryu under 17th headmaster Sasamori Takemi and 18th headmaster Yabuki Yuji.

http://about.me/grigorismiliaresis