From Temples to Dojos: Zen’s Influence on Samurai and the Martial Arts

My first experience in martial arts and meditation began in elementary school, where each martial arts class ended with a meditation. Although I’ve forgotten the details of those early meditations, the calm enjoyment I felt remains vivid. That experience laid the foundation for the path I would later return to as an adult.

After college, I joined a kobudo martial arts school and met an instructor who had studied Zen in Japan. His Saturday morning meditations became my formal introduction to Zen. Then, in 2001, I took a leap of faith. I left my career in architecture and moved to Japan to study martial arts and meditation. For the next 20+ years, I’ve remained in Japan, training in both kobudo and various forms of meditation including Shugendo, Shingon Buddhism, and Zen. Currently, I practice Zen at Kakuoji Temple in Tsukuba, under Hanabusa Jushoku, who generously shared his insights for this article.

By Robert R. Gray

Robert R. Gray

Introduction

Zen Buddhism has had a profound influence on samurai culture and the martial arts of Japan. When Zen was first introduced to Japan during the Kamakura period (1185-1333), the samurai were quick to adopt it, finding that many of the concepts resonated deeply with their own practices. This integration of Zen into samurai culture influenced not only their combat effectiveness, but also their philosophical and artistic pursuits.

The Journey of Zen: A Brief History

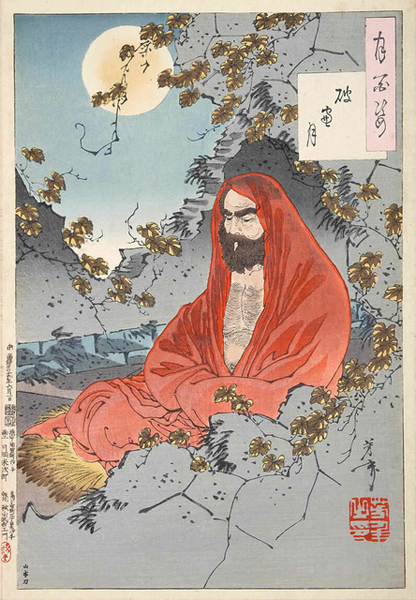

Zen Buddhism originated in India and made its way to China around the 6th century CE, when the Indian monk Bodhidharma was welcomed by the Shaolin Temple to teach Buddhism. The Shaolin Temple eventually became famous for being the birthplace of both kung fu and Zen, (known as “Chan” in China).

Bodhidharma

During the 12th century, Zen was brought to Japan by several Japanese monks who had traveled to China to study. The most notable were Eisai, Dogen, and Ingen. Eisai established the Rinzai school of Zen, Dogen established the Soto school, and Ingen, the Obaku school. Samurai patronage of their temples allowed Zen to spread quickly throughout Japan.

However, the fact that samurai were patrons of Zen temples, doesn’t mean that all samurai, or even most of them, studied Zen seriously. The percentage of dedicated samurai practitioners was known to be small. Zen’s influence instead, came in the form of guiding and enhancing existing samurai beliefs and practices. We’ll look at some examples of this in the next section.

Zen continued to influence bushido (the way of the warrior) until 1868, when the samurai class came to an end and power was restored to the Emperor. This transition of power was intended to modernize Japan and promote a sense of national unity under the new Meiji government. As part of the transition, the government made Shinto (a Japanese religion) the official religion, creating a serious challenge for all others. This shift towards suppressing foreign religions, combined with the abolishment of the samurai class, led to a dramatic decline in support for Zen temples. In a few short years, Zen’s once booming echo was reduced to a whisper.

Kakuoji Temple in Tsukuba

Ironically, while Zen was declining in Japan, it began spreading in the West. During the Meiji period (1868-1912), Japan opened up to trade, giving Westerners their first exposure to the mysterious and paradoxical teachings of Zen. As interest grew, Japanese Zen masters started to travel and teach abroad. Over time, influential figures such as D.T. Suzuki, Shunryu Suzuki, Alan Watts, Erich Fromm, and others played a pivotal role in introducing Zen to the West.

Zen and Samurai Commonalities

Zen was readily adopted by the samurai because they share a number of commonalities. It may sound strange that the samurai, a military class which regularly engaged in violence and war, would have anything in common with Zen, a Buddhist religion that emphasized peace, compassion, and acceptance. But Zen priests were dedicated to the salvation of all humans, and introducing their methods to the samurai was a way to help them achieve that. In return, the temples received generous patronage from the samurai. In this way, Zen continued to spread with mutual benefit. Interestingly, it was the Zen priests who were teachers to the ruling samurai, not the other way around. So, what common views did they share?

1) Focused Concentration

Focused concentration is a cornerstone of both Zen and samurai culture as it reflects the importance of being mindful and aware. Zen practice cultivates mindfulness through meditation, which sharpens focus and leads to inner calm. Similarly, samurai developed focus as a way to maintain clarity and awareness in the heat of battle.

2) Action Over Thought

Another commonality was that both Zen and samurai culture emphasized the value of action over excessive thought. Rather than getting lost in overthinking and analysis, Zen encourages individuals to act decisively in each moment, focusing on experience and intuition. (This is quite different from Western philosophy, where great importance is placed on thought, represented by works such as Rodin’s statue, “The Thinker.”) In samurai culture, taking decisive action was considered essential for demonstrating discipline and duty. There was no time to waste pondering responsibilities. This principle was particularly important in combat, where overthinking or hesitation could be fatal. The disciplines of samurai and Zen both prized having a mind which responded freely and spontaneously.

3) Facing Death

Both Zen and samurai culture emphasized the impermanence of life and the inevitability of death. In Zen philosophy, the concept of impermanence, or “mujo” emphasizes the transient nature of all things, including life and death. By letting go of worldly attachments and accepting death as a natural transition, Zen practitioners can experience a sense of peace and liberation.

The samurai had similar things to say in texts such as the “Hagakure” and “Budo-shoshinshu.” The Budo-shoshinshu was written in the early 1700s to provide ethical, social, and philosophical guidance to young samurai. This quote from the document sums it up well:

The most important thing for a warrior is to keep death in mind at all times. If you assume you will live a long time, you’ll wish for various things and become desirous. You’ll want what others have and develop the mentality of a merchant. If, on the other hand, you accept the inevitability of death, and always keep it on your mind, you won’t develop a greedy attitude. You’ll understand what’s most important. You’ll feel the weight of every word you speak, and you’ll avoid useless arguments. Because of this, your character will grow.”

For the samurai, the acceptance of death was important not only for building character and fighting bravely in battle, but also for the practice of seppuku. Seppuku was a form of ritual suicide that allowed a samurai to die with dignity rather than be captured or face dishonor. By performing the ritual in a calm, dignified manner, the samurai demonstrated that they could face death fearlessly and thus die honorably.

4) Interest in Poetry

A surprising connection between Zen and samurai culture was their mutual interest in poetry. Many famous samurai such as Ashikaga Takauji, Takeda Shingen, Hojo Ujiyasu, and others were not only skilled warriors, but also famous poets. Takeda Shingen even invited nobles over to his castle for poetry gatherings.

In the world of Japanese poetry, there is a genre known as “jisei.” Jisei poems were originally composed by Buddhist monks towards the end of their lives as a way to reflect on the transitory nature of life. While the term “jisei” is often translated as “death poem,” the kanji characters tell a slightly different story. The kanji “辞世” (jisei) means to “resign from the world,” which in Japanese culture is an indirect, and therefore more respectful way to approach to topic of death.

The practice of writing jisei near the end of one’s life resonated with the samurai and steadily grew in popularity. Let’s look at an example of a samurai jisei from the book I’m currently translating, “Whispers of the Departed.” The following poem was written by the samurai Shimazu Yoshihiro, also known as “Demon-Shimazu.” Despite his famed ruthlessness, he was also a devoted Zen Buddhist. The Buddhist influence on his poem is apparent in his exploration of emptiness and the fleeting nature of things:

In spring and autumn

The flowers and leaves don’t last

They all disappear

People are emptiness too

All things return to the source

5) Munen-muso (No Thought, No Mind)

Hanabusa Jushoku, the head priest of Kakuoji Temple writes, “Munen-muso is a teaching that connects Zen and bushido. In Zen, clearing your mind of thoughts includes getting rid of desires and illusions. To be free of all of these is the ultimate purpose of Zen—in other words, the state of munen-muso.”

This Buddhist term also appears in the kobudo school called “Kukishin ryu” as the name of one of the hanbo (short staff) postures. In that school, the meaning of the term has evolved into “not giving off intention and becoming one with nature.”

6) Enlightenment

In Zen Buddhism, enlightenment, or “satori” is the sudden realization of one’s true nature—an awakening to the interconnectedness of all things. It involves letting go of the ego and perceiving reality directly, free from all illusions, including the illusion of self. This realization is not merely intellectual, but an experience of transformation sometimes achieved through the practice of the seated meditation known as “zazen.”

For martial artists, enlightenment is sometimes reached through rigorous training, where the ego is transcended, and the state of “mushin” (no-mind) is reached. Despite the different paths, they both represent a letting go of the self and entering into a state of oneness, sometimes called mushin.

Samurai and Zen-Master Relationships

1) Among the relationships between samurai and Zen masters, one the most famous was the relationship between the samurai Yagyu Munenori and Zen master, Takuan Soho. Takuan wrote a series of fascinating letters to Munenori, who was the shogun’s sword instructor and founder of the Yagyu Shinkage ryu sword school. The letters were published in a document known as the “Fudochi-shinmyo-roku” and detailed how to apply Zen philosophy to swordsmanship.

2) Ashikaga Takauji (1305-1358) was a heroic figure of the Muromachi period (1338-1573). He is best known for conquering the Kamakura shogunate and becoming the first Ashikaga shogun. In addition to his military accomplishments, he was also an accomplished poet with 86 poems published in imperial anthologies. Furthermore, Takauji was a serious Zen practitioner who studied under Zen master Muso Soseki. In a document called the “Baishoron,” Soseki described Takauji as “brave in battle—smiling even in the face of death.”

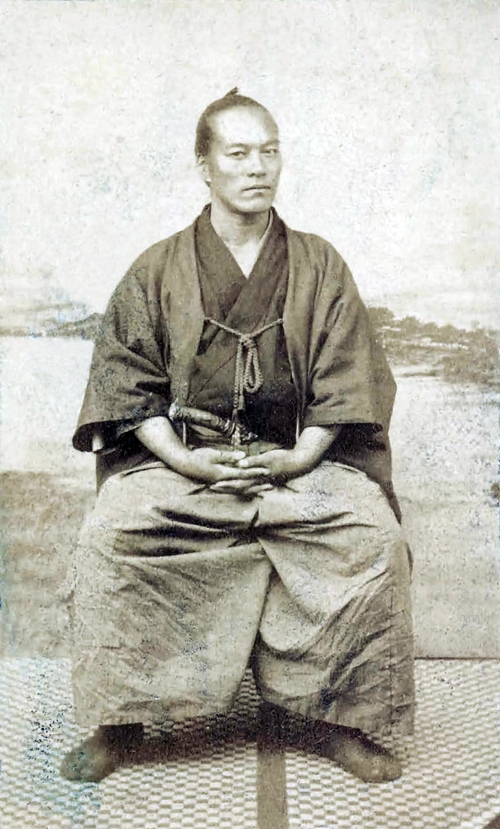

3) Yamaoka Tesshu (1836-1888) was not only a master swordsman, but also a master of Zen, completing his study under Seijo of Ryutakuji Temple. Tesshu first gained fame as a samurai when he became the bodyguard to Shogun Tokugawa Yoshinobu. After reaching enlightenment, he founded the Itto-Shoden-Muto-ryu sword school, combining swordsmanship with Zen. His school was based on the principle of mu-to or “no-sword,” which he described as: “There is no sword outside of one’s mind. When you face an enemy, attack his mind with your mind rather than relying on your sword. This is mu-to.” In his final days, he was diagnosed with stomach cancer. He got up one evening, wrote his jisei poem, and sat down to meditate. He died later that evening, still seated in zazen.

Yamaoka Tesshu

Resolving Contradictions

Despite the commonalities, there are some fundamental differences between Zen and samurai culture. While Zen aims to save others and oneself, samurai trained to kill others and sometimes even oneself. When I asked Hanabusa Jushoku about these conflicts between the two, he referred me to the Zhuang-zi text and the teaching of “両忘” (ryobo), which means “forgetting both.” “Both” in this case, refers to any two things in conflict, such as good and evil, life and death, and so on. The idea here is that in wholeness (oneness, emptiness), the two opposites are forgotten and no contradictions arise.

Robert R.Gray and Hanabusa Jushoku