Mikkyo Influence on Martial Arts

Text by Robert R. Gray

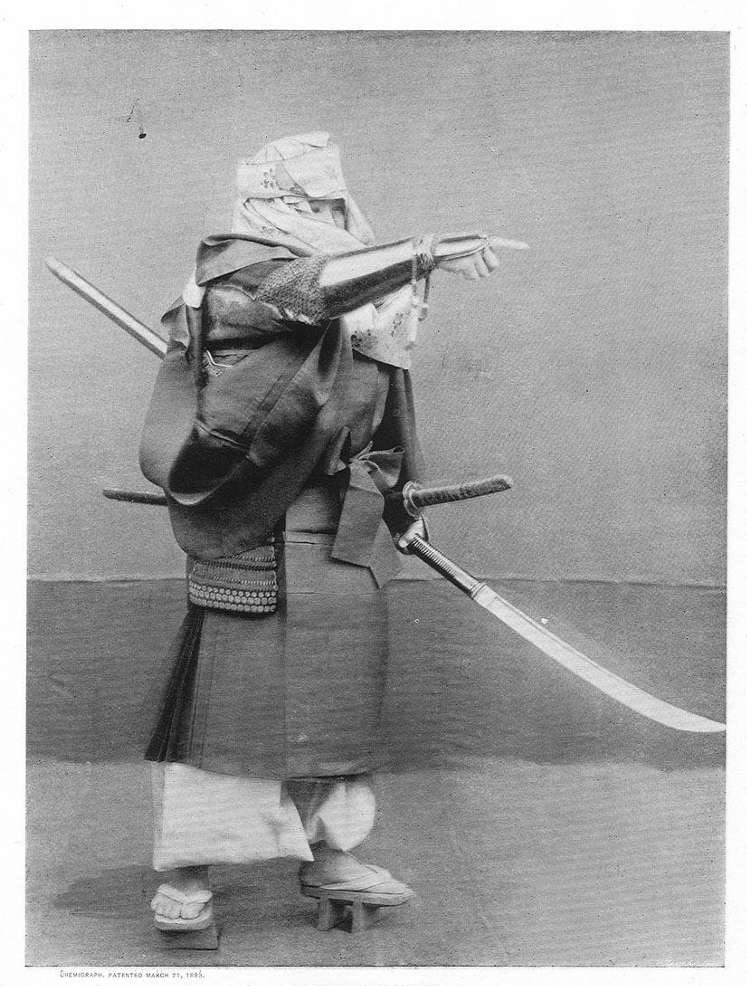

Sohei(A Fighting Monk), Military Costumes in Old Japan, 1895 (Meiji 28)

Introduction

Esoteric Buddhism, known as “Mikkyo” in Japanese, had a profound influence on the development of Japanese martial arts. Infusing ritual and philosophy into warrior culture, Mikkyo created a fusion where spiritual practices and martial training became intertwined. This integration gave rise to a paradox: warrior monks caught between Buddhist precepts of nonviolence and the brutal realities of feudal Japan. In this article, we explore Mikkyo’s esoteric practices and how they shaped the evolution of sohei (warrior monks), samurai, kobudo (traditional martial arts), and ninjutsu.

Part 1: The Rise of Mikkyo and the Warrior Monks

The roots of Mikkyo trace back to the Shingon and Tendai sects of Buddhism. Shingon was brought to Japan by Kukai in 806 CE, following his studies in China under the esoteric master Huiguo. After receiving full transmission and authorization to teach, Kukai returned with sacred texts, mandalas, and ritual implements, eventually founding Japan’s first Shingon temple, Kongobu-ji, on Mt. Koya.

Priest on Mt. Koya (photo taken by author)

Around the same time, Saicho returned from China with the teachings of the Tendai school and established Enryaku-ji Temple on Mt. Hiei. Situated near Kyoto, the temple was favored by the Imperial Court, which helped it expand into a sprawling complex of nearly 3,000 buildings. Together, these mountaintop temples of Shingon and Tendai have remained influential monastic centers for over a thousand years.

Enryaku-ji Temple on Mt. Hiei

However, the generous court donations that Enryaku-ji received came with strings attached. The Imperial Court felt this gave them the right to appoint the temple’s next leader. When Enryaku-ji’s monks refused a court-appointed zasu (abbot), samurai troops were sent in to enforce their decision. The temple yielded, but resentment simmered.

Sohei of Kofuku-ji(from Kasuga gongen kenki)

Tension over court appointments continued to rise until the year 970, when Ryogen—Enryaku-ji’s leader—made the decision to create a fighting force to protect its interests. This act contradicted a policy Ryogen had issued earlier that same year, forbidding monks from carrying weapons or engaging in violence. His reversal of policy is made clear in the Sanka Yoki Senryaku (Abridged Records of Mount Hiei), which quotes Ryogen as saying: “On Mount Hiei, in order to guard the true Dharma, to secure oil for lamps, and to defend the temple lands, warrior practitioners are needed. Therefore, monks who are foolish and have the least amount of talent should be assigned to that role.” So when the sohei system first began, it was the monks least suited to quiet monastic life who were chosen to become warrior monks.

The next time the Imperial Court attempted to appoint someone they didn’t like, Enryaku-ji’s warrior monks marched into Kyoto to protest. The Court called in samurai troops for support and a bloody battle began—but this time, it was the monks who were victorious. A document known as the “Taiheiki” captures their defiance: “When tyrants disturb the land, we borrow divine power to drive them back.”

Benkei and Ushiwakamaru, 1811(William Sturgis Bigelow Collection Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

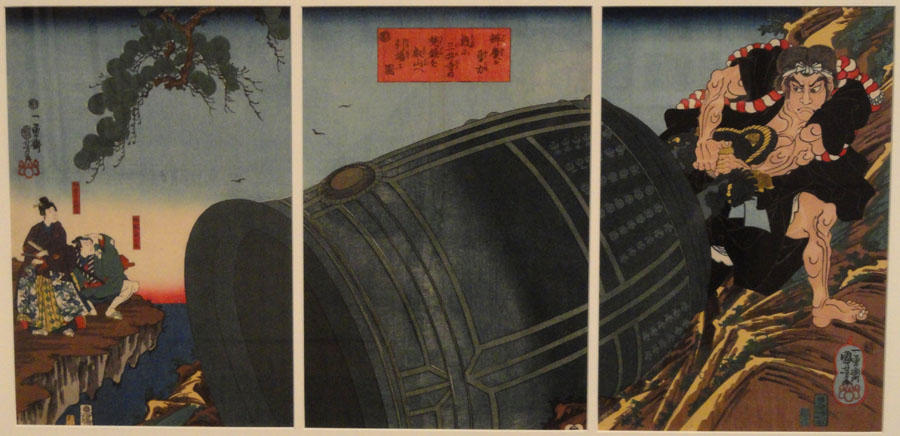

Among these warrior monks, the most legendary was Benkei—a figure woven from both fact and folklore. He began his training at Enryaku-ji Temple but was eventually expelled for misconduct. After wandering the mountains, he took up residence in an old, abandoned shrine that lacked a temple bell. Known for his size and strength, Benkei is said to have stolen a massive bell from Miidera Temple—Enryaku-ji’s main rival. According to legend, he dragged the bell across the mountains to his new home. But when he rang the bell, it would only make a strange sound, as if moaning to return to Miidera.

Benkei Stealing Bell(Benkei ga yûriki tawamure ni Miidera no tsurigane wo Hieizan e hikioguru zu, Iba-ya Sensaburô, 1845)

During the Edo period (1603-1868), theater performances became popular and Benkei came to be portrayed as both fierce and funny. The idea eventually emerged that Benkei had a weak spot—his shin, a spot so tender that even Benkei would cry if struck there. This sensitive area was called “Benkei-no-nakidokoro” (Benkei’s crying spot) and the term is still used today whenever someone happens to hit their shin.

In contrast to Enryaku-ji, Mt. Koya’s Shingon temple was less politically active and never developed warrior monks. However, the Shingon sect’s Shingi branch developed its own militant force at Negoro-ji Temple. Around 1560, the Jesuit missionary Gaspor Vilela visited the temple and described what he saw in his travel diaries: “Their swords cut through armor like tender meat. Their training was intense and the death of one of their members during practice was met without emotion.”

Part 2: Mikkyo Practices and Influence on Budo

At the heart of Mikkyo lie three essential elements: mudras (symbolic hand gestures), mantras (sacred chants), and mandalas (spiritual diagrams). Together, they are connected to the “three mysteries” (sanmitsu—the mysteries of body, speech, and mind) and form a three-pronged weapon against the mind’s tendency to wander. They aim to unify the body (mudra), speech (mantra), and mind (mandala visualization) into one. Ultimately, they are to help the practitioner transcend duality and attain enlightenment. Let’s look at them in more detail:

Mudras: Specific hand gestures believed to channel energy and offer protection. Early warrior traditions adopted mudras from Mikkyo, using them as a way to gain protection and alter their mental state in combat.

Mantras: Chanted phrases intended to center the mind and call upon divine assistance. A mantra is not a magical spell like one might say at Hogwarts, but rather a device to focus the mind by keeping distracting thoughts at bay. In practice, the name of a deity is often recited to invoke their guidance and protection.

Mandalas: Visual representations of the two realms. The two realms of Mikkyo are the taizokai (womb realm), symbolizing the world of everyday phenomena, and the kongokai (diamond realm), representing ultimate truth.

Early samurai who supported the temples began adopting some of these practices. By the 1400s, mudras and mantras had entered into the teachings of Katori Shinto Ryu, one of the earliest foundational schools of kobudo. By the 1600s, Mikkyo had seeped into the shadows of ninjutsu.

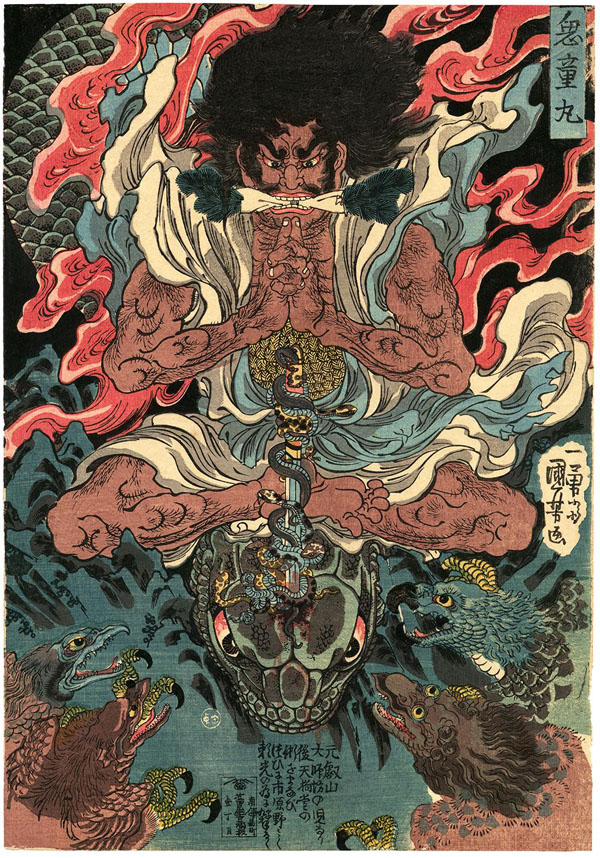

Kaido-maru wo taijisuru no zu (Utagawa Kuniyoshij, 1843)

Yet, as Mikkyo made its way into the martial arts, its purpose began to shift. In traditional Shingon practice, rituals were meant to offer protection from obstacles to enlightenment, such as distraction and desire. But within the warrior traditions, “protection” came to mean “protection in battle.” The purpose became more practical than spiritual.

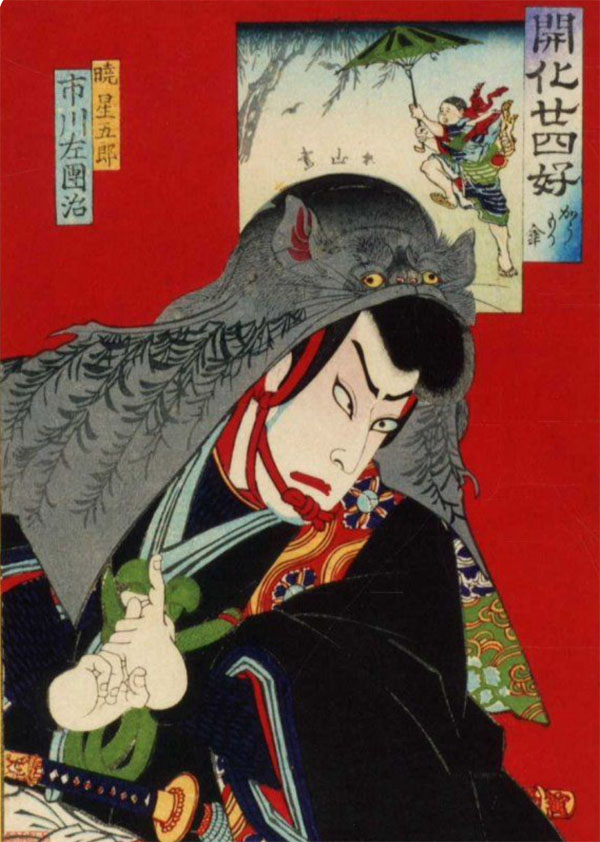

Samurai mudra(The Bandit Akatsuki Hoshigoro, Toyohara Kunichika, 1877)

Mikkyo Rituals

One well-known ritual is the kechien-kanjo, a ceremony open to both monks and laypeople. Samurai were especially drawn to it as they believed it offered protection in battle without requiring them to take monastic vows. A key part of the ceremony involves a practice called toke-tokubutsu, where the participant is blindfolded and tosses a flower onto a mandala. The deity the flower lands on is believed to become that person’s protector, forming a sacred bond between them.

A more advanced ritual is the denbo-kanjo, in which a disciple becomes a fully authorized Ajari—a master teacher of esoteric Buddhism. This initiation has strict prerequisites, including the recitation of 100,000 mantras, a process that typically takes at least two to three years. After this, the disciple takes special vows and receives the secret mudra and mantra teachings known as kuden—oral transmissions never to be written down. Interestingly, many kobudo schools also use this kuden system to transmit their highest-level techniques.

The peak of the denbo-kanjo ritual is the nyuga-ganyu meditation, in which the candidate merges with the central deity, Dainichi Nyorai. The aim of this meditation is to have the boundary between self and deity dissolve and enter into a state of oneness. Upon completing the ritual, the disciple is formally recognized as a true teacher—often regarded as a living embodiment of a deity in the world.

Samurai Supporters of Mikkyo

Minamoto no Yoritomo (1147-1199)

In 1185, Yoritomo founded the Kamakura Shogunate and had Tendai monks perform the goma fire ritual to both celebrate his success and purify karmic sins caused by the Genpei War. Recognizing the political value of having the powerful warrior monks on his side, Yoritomo gave official protection to Enryaku-ji.

Ashikaga Takauji (1305-1358)

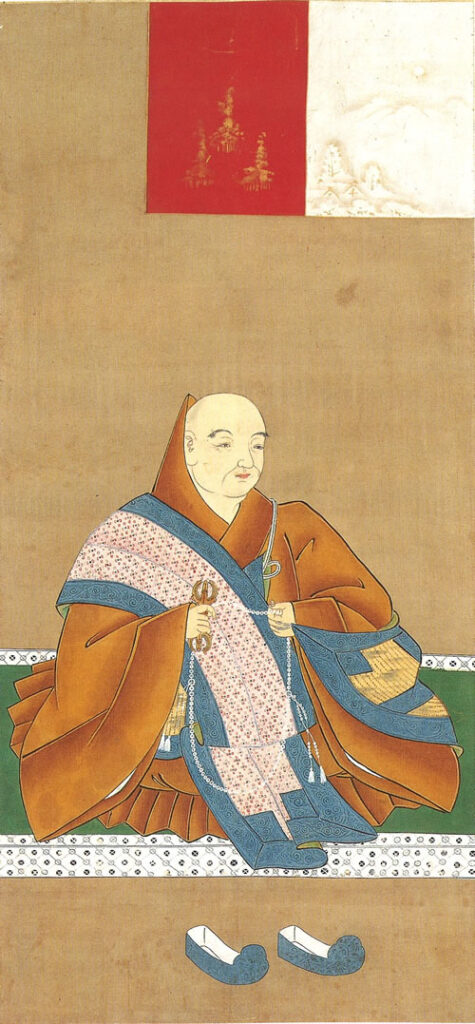

Takauji founded the Ashikaga Shogunate and was a devoted patron of Shingon Buddhism. Although he never became a priest himself, he formed a close alliance with Kenjun, the chief abbot of Daigo-ji Temple and a prominent Shingon master. According to Kenjun’s diary, he conducted rituals for national peace and the protection of the Ashikaga regime. The Gohachidaiki record states that Takauji even had Kenjun accompany him on military campaigns in order to consult with him on important matters. One document preserved at Daigo-ji Temple states that Kenjun made a self-sacrificial ganmon vow to absorb any misfortune that might otherwise fall upon Takauji.

Sanbō-in Kenshun, 1390

Kokuho Kenjun Shojo(Daigoji Cultural assets Archives)

Saito Toshinaga (?-1460)

Toshinaga was the head of the Saito clan during the Sengoku period. After years of battle, he renounced war and became a Tendai monk at Enryaku-ji Temple. Eventually, he underwent the denbo-kanjo ritual and became a fully ordained Mikkyo priest.

Uesugi Kenshin (1530-1578)

Kenshin regularly engaged in kaji-kito—esoteric rituals for protection—before going into battle. He also saw himself as the embodiment of Bishamonten, the Buddhist god of war. This idea of merging one’s identity with a Buddhist deity was derived from Mikkyo philosophy.

Kuji-in: The Nine Syllable Seals

Kuji-in—the nine symbolic hand seals—is a practice rooted in Shingon Mikkyo and closely associated with deities such as Fudo Myo-o. It involves a sequence of nine mudras performed while chanting corresponding syllables: Rin, Pyo, To, Sha, Kai, Jin, Retsu, Zai, Zen. Each syllable-mudra pair is believed to invoke a specific spiritual energy. Sha, for example, represents harmony, balance, and self-awareness.

The earliest form of the kuji concept can be traced back to the Baopuzi, a Taoist text from the early 4th century CE. While this text doesn’t mention any hand gestures, it does describe a similar version of the nine syllables to ward off misfortune. The practice evolved over time as Taoist ideas merged with Vajrayana Buddhist rituals during China’s Tang dynasty, and these blended traditions were later brought to Japan through Shingon and Tendai Buddhism. Mudras were added to the nine-syllable mantra during this period of integration with Shingon. As the samurai class grew and warfare became a way of life, so did the appeal of this kuji ritual promising protection.

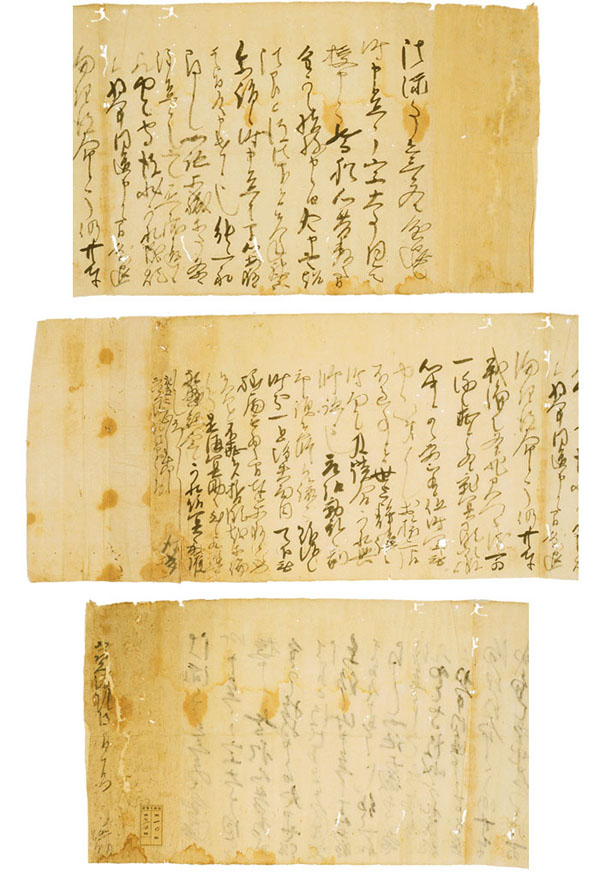

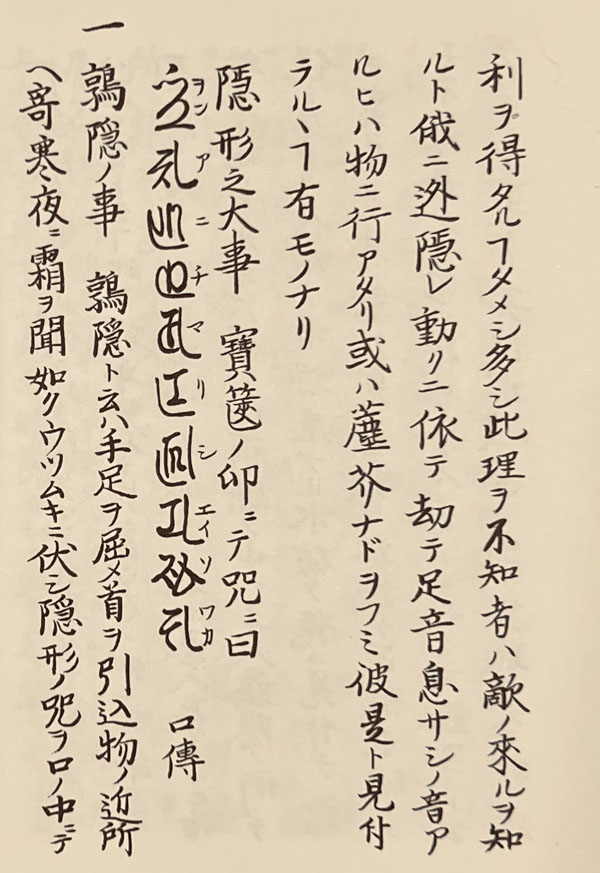

By the 17th century, kuji-in had found a new form of expression in the historical ninja manuals, such as the Bansenshukai (1676). There, the practice is linked not just to protection, but to invisibility—specifically through a ritual invoking Marishiten, the goddess of stealth and illusion:

“When hiding, lie face down, so the sound of your breathing becomes harder to detect. Focus your attention and empty your thoughts. Then, while using the Marishiten invisibility mudra (left hand covered by the right) chant the following mantra:

“On A Ni Chi Marishi Ei Sowaka.”

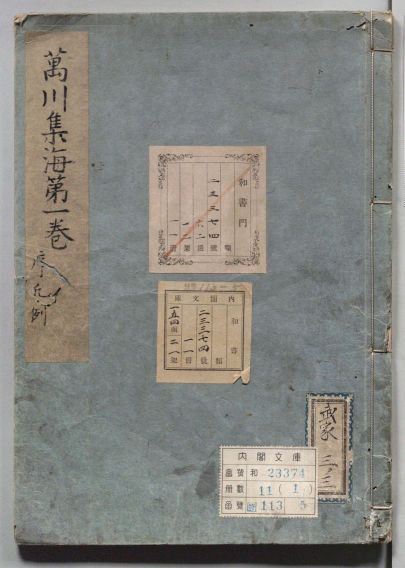

mansensyukai

On A Ni Chi Marishi Ei Sowaka

What’s particularly interesting about this passage is that it shows the practical and psychological aspects of kuji—such as quieting the breath and clearing the mind—rather than relying on supernatural forces alone.

On Fudoshin

Fudoshin is a concept derived from the Buddhist deity, Fudo Myo-o, who symbolizes the force that cuts through delusion to help people attain enlightenment. In Mikkyo, fudoshin represents the immovable, ultimate truth of the universe. In martial arts, the meaning changed to represent an unshakable calmness and composure in combat.

Mount Fuji of the Ascending Dragon,Katsuhika Hokusai, 1834-35

Conclusion

Mikkyo resulted from a fusion of Taoism and esoteric Buddhism. Over time, Mikkyo priests took up arms to defend their temples, blending spiritual practice with warrior traditions. As these esoteric rituals spread into samurai culture, kobudo, and ninjutsu, their purpose shifted—from the pursuit of enlightenment to protection in battle. Even today, traces of these ancient practices live on—not just within Tendai and Shingon Buddhism, but also within kobudo schools such as Katori Shinto Ryu.