Bridging Two Worlds: Guillaume Erard on Aikido and Daito-ryu

His online work in aikido, Daito-ryu and koryu is so prolific that before I met him and exchanged life stories, I was under the impression Guillaume Erard has been in Japan for ever! However, the French biologist and martial arts instructor, now at his 6th aikido dan from the Aikikai Honbu and his 5th Daito-ryu Aiki-jujutsu dan and kyoshi license from Chiba Tsugutaka’s Shikoku Hombu Dojo has been in Japan as long as I have -the difference is that he spent his decade here creating amazing written and video content published on his website and his YouTube channel which has over 70,000 subscribers and has helped define the way Westerners understand martial arts’ (and especially aikido and Daito-ryu) practice in Japan with his down-to-earth, realistic presentation of the situation here as it is. Between his reporting, research into the roots and history of his arts (some of which we have seen here in “Hiden”) his teaching aikido at the Yokohama Aikidojo and his understanding of life in Japan on one hand and his uniquely cosmopolitan perspective coming from what is arguably Europe’s capital of Japanese martial arts and having also lived in the UK for several years, Mr. Erard is one of the most interesting voices in the world of Japanese martial arts so we had to have a sit-down and talk about his two arts.

Grigoris Miliaresis: I won’t get into your CV –it’s on your website for everyone to see and besides, aikido and Daito-ryu practitioners already know you! I prefer to go directly to your practice and ask, after having practiced in Japan for ten years, what is it that you feel you’ve gained from practicing here instead of overseas?

Guillaume Erard receiving his fifth dan from Ueshiba Moriteru Doshu at the Aikikai Hombu Dojo.

Guillaume Erard: Even though aikido is supposed to be practiced by anybody across the world, Ueshiba Morihei himself can’t be understood in isolation of his culture and historical context. Consequently, I realized that if I wanted to really understand aikido, I needed to understand Japan, its culture, its history and its language. Practicing at the Aikikai Hombu Dojo allowed me to train as often as I wanted with some of the best teachers in the world, but more importantly, training with Ueshiba Moriteru Doshu made me realize aikidoka are bound by an unbroken lineage. Doshu is a living connection with aikido’s history and even today, I still feel a great sense of respect every time I pass in front of the Ueshiba family home and enter the dojo. I also got the chance to practice with, and even interview a number of direct students of O-Sensei such as shihan Tada Hiroshi, Isoyama Hiroshi and Kobayashi Yasuo. They were all very generous with their time as they patiently answered my questions, and some even gave me some material to continue my research. As I got more familiar with Japanese culture and language, things slowly started to make more sense.

Inagaki Shigemi Shihan, Guillaume, Kei Izawa (International Aikido Federation Chairman), and Isoyama Hiroshi Shihan at the Aiki Shrine. Guillaume has built a strong relationship with the International Aikido Federation over the years and he collaborates regularly to its activities.

And if you were to compare practice in Europe and practice in Japan?

If aikido is to be universal, then it needs to address the needs of the people who practice it, wherever they are. In this sense there are indeed differences. For instance, in Japan, budo training is a “人間形成の道” (ningen keisei no michi) a way for character development, and combat efficacy is not the main goal, while in some other countries there are real public safety concerns, so citizens there might want to do aikido for self-defense; therefore, training methods and techniques will be different. It’s hard to generalize though, and some people may use aikido as a way of meditation and others as an educational tool. All interpretations are valid as long as they suit their respective contexts and as long as people who teach, deliver on their respective claims. On the other hand, one aikidoka does not have to be held accountable to the claims of another.

Guillaume demonstrating Aikido as part of the International Aikido Federation delegation during the World Martial Arts Masterships in Korea

Aikido descends from Daito-ryu but it looks much more flexible in its forms and interpretations -why is this?

People often say that aikido is based on Daito-ryu techniques and Omoto thinking, yet most of O-Sensei’s students I’ve talked to, have told me that they understood very little of what O-Sensei was saying. I’m not very knowledgeable about Omoto religion but I studied its history in detail, and I can say it had strong universalist ambitions. For example, Deguchi Onisaburo reckoned that “adapting” Omoto in Esperanto was the key to its universal spread. Morihei shared Onisaburo’s universalist vision and that’s why I think Kisshomaru Doshu was in line with his father’s intentions when he turned aikido into a global art. To do so aikido’s techniques and, to some extent, its message were modified to suit every place on earth where it was introduced. Daito-ryu on the other hand doesn’t allow such degree of flexibility, I think, and that might be the reason it has remained more secretive until recently.

So you would say that Daito-ryu is more down to earth, more physical?

Yes and no. Many people think that Daito-ryu practitioners don’t care about others, but it’s not true. I can’t speak for earlier times but Nowadays, there is a strong moral component to Daito-ryu. If you look at what Takeda Tokimune said:

The goal of Daito-ryu is the spread of “harmony and love”, keeping this to heart helps maintain and achieve social justice. This is the desire of Takeda Sokaku.

Takeda Tokimune – Speech reported by Ishibashi Yoshihisa in “Takeda Sokaku Den, Daito-ryu Aiki Budo Hyakujuhachikajo” (p. 51)

It sounds similar to a number of things that Ueshiba has said so I don’t believe that the difference is on the goal, but rather, on the intended audience. Aikido aims at spreading harmony throughout the world, but Daito-ryu has remained largely Japan-centered.

You said that aikido has undergone some changes (was “modified”) outside Japan and having practiced both here and overseas you are certainly qualified to judge that. Could you be more specific on what these modifications are?

That’s one of its most fascinating aspects! Since we just mentioned harmony, it is easy to translate “和の武道” (wa no budo) in English as “budo of harmony”, but different cultures will understand “harmony” in very different ways. In the West, most people understand “harmony” as an ideal of peace and mutual understanding through unconditional love and forgiveness, which possibly comes from our Judeo-Christian roots. This is visible in the journal of André Nocquet, who was O-Sensei’s first foreign uchi-deshi (see “Hiden” July & August 2020). This is very different from the more pragmatic interpretation of “和” (wa) in Japanese society: people in Japan can be in harmony without knowing or liking each other; they just need to operate on the same set of social rules, and everything goes smoothly. This is an efficient way to live as a society and I wish my fellow Frenchmen would think a little like that, but in France, our motto is “freedom, equality, fraternity”.

In Kyoto with Christian Tissier Shihan, who has been a source of inspiration for Guillaume throughout his life as an aikido practitioner.

Even though the 1789 revolution and the May 1968 protests have led the French people to more “freedom”, the side effect was an excessive individualism. If the French were to embrace the Japanese interpretation of harmony, they would have to accept to live by a set of rules meant for the greater good, and limit some of their individual freedom. The current issues around wearing masks during the Covid-19 pandemic is a good example of that: Japanese people are very diligent about protecting those around them, but some people in France consider it as a violation of their individual freedom. Furthermore, “和” doesn’t require “equality”; it just assumes that people have their place in the social order, and that they function within those boundaries. In Japan, things are set from the start, you have your sensei, sempai, kohai, and the order never changes. In France, people assume that they may equal or outrank anybody. As for the moral bond of “fraternity”, I see less of it these days, most likely because the other two are so prominent.

Guillaume has produce a number of interviews with aikido’s most prominent instructors over the years. Here with Tada Hiroshi Shihan (2017).

I take the example of France because I know it best but whatever the country, there might be substantial cultural and philosophical differences. This is why evangelizing “和” beyond Japan, even with good intentions, may cause some friction. In its extreme, “和” can be closer to the Romans’ Pax Romana than a hippy community; “和” can, in fact, be spread by force, like it was during WWII when the military, or people like Deguchi Onisaburo or even Ueshiba Morihei, all wanted to spread “和” outside Japan. What made Ueshiba Morihei truly remarkable is that he decided that violence was no longer an acceptable means to do so. It’s easy nowadays to criticize Morihei’s connections with shady characters from far-right organizations, but observed in the context of the time, his moral stance was pretty special, if not revolutionary.

Let’s go back to you: why did you start studying Daito-ryu?

Though one may speak French fluently, if one wants to deeply understand it, one must study its Latin roots. I think it’s the same for aikido. Obviously, O-Sensei’s students were devoted to their master’s teachings so they couldn’t or wouldn’t teach me the roots of his techniques, so I started to wonder if it was still possible to learn Daito-ryu today. Mr Olivier Gaurin introduced me to Kobayashi Kiyohiro Sensei, an 8th Dan Kyoju Dairi student of Hisa Takuma. Interestingly, Kobayashi Sensei also studied under Nakamura Tempu and he trained at the Aikikai while O-Sensei was alive. That makes him an incredibly precious teacher, a sort of living encyclopedia of Daito-ryu and aikido techniques. He understands how an aikidoka like me thinks and moves, and he is able to explain Daito-ryu techniques to me very clearly. For the first time, I got clear answers to my questions about the origins of aikido techniques and their history, so I enrolled as his student after my first class with him, and I still follow him today.

Guillaume Erard and Olivier Gaurin with Kobayashi Kiyohiro Sensei, the two people who introduced him to Daito-ryu.

Seeing my commitment to Daito-ryu, Olivier introduced me to Chiba Tsugutaka shihan, one of the most senior Daito-ryu instructors in Japan. Chiba Sensei was the successor of Nakatsu Heizaburo, who was one of the most advanced practitioners at the Asahi Newspaper, and whom you can see prominently in the “Soden” the extensive set of pictures documenting the techniques taught by Ueshiba Morihei and Takeda Sokaku at Osaka’s Asahi Shinbun from 1934 to 1939. Chiba Sensei also studied under Hisa Takuma and Takeda Tokimune and he was appointed by Tokimune as representative of his Daito-ryu in Shikoku.

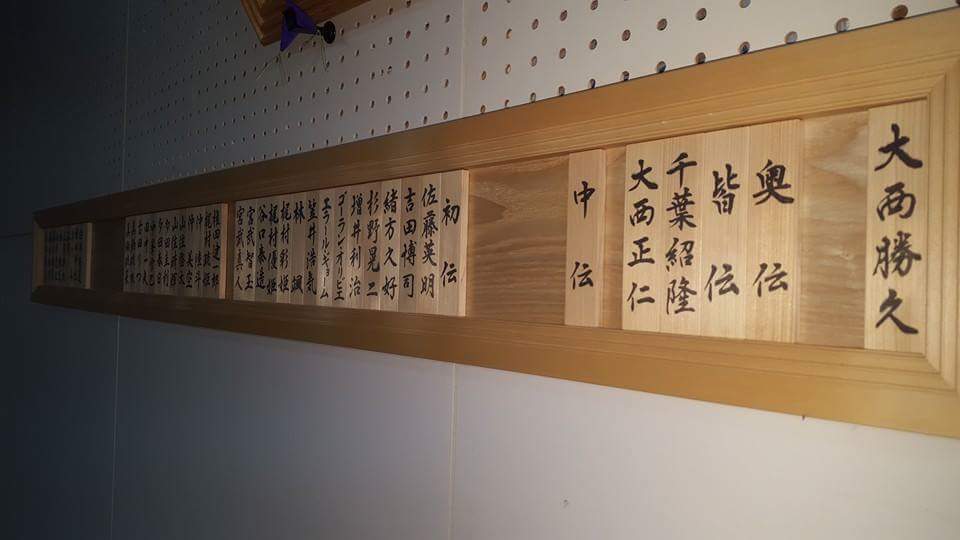

Nafudakake of the Shikoku Hombu Dojo

If through Daito-ryu you came to such a level of understanding, why did you keep practicing aikido?

Chiba Sensei once told me that we are all branches that stem off the same trunk, and that as long as each branch knows where its connection is, the trunk keeps getting stronger. Many lines in Daito-ryu and aikido have gradually branched out in different directions and they should all be cherished because they all bring something invaluable to the trunk and to the world. Takeda Tokimune and Ueshiba Kisshomaru both had to follow in the footsteps of their genius fathers, and though they approached things differently, we owe them both an incredible debt of gratitude for having made sure that their fathers’ lines can be studied today. I am a student of the Aiki tree, so I can perfectly study several of its branches at the same time.

Chiba Sensei instructing Guillaume on the way to introduce European students to Daito-ryu.

As I learned more about aikido and Daito-ryu, I started to understand why different schools did things in different ways. Instead of saying things like: “This teacher/school is wrong, kotegaeshi should not be done like that, but like this!”, I started to think: “Oh, I understand where their form of kotegaeshi comes from!” I started to see how other people’s technique fitted in the larger Aiki framework. Knowledge always leads to understanding and understanding leads to appreciation.

What does aikido bring to your Daito-ryu practice?

Daito-ryu is not a monolithic entity: there have been some substantial developments and shifts in its various branches. As an aikidoka who is used to applying techniques in a free and dynamic environment, I can adapt quickly to different ways to do things; in fact, experienced aikidoka who take up Daito-ryu often progress quickly because their perception and ukemi are already developed and they perceive the connections among Daito-ryu’s many techniques.

How do you think all this knowledge manifests in you?

Christian Tissier Shihan kindly regularly puts his dojo at Guillaume’s disposal to conduct seminars when he returns to France.

Its whole is greater than the sum of its parts. By doing both, I internalize the principles better and I also feel freer when I teach because what I do is always the product of a choice from a large spectrum of techniques –I am not restricted to a single school’s way of doing things. On the other hand, I am also respectful of the lines, so when I’m training at the Aikikai Hombu, I do Hombu’s aikido, and when I’m in Shikoku, I do Chiba Sensei’s Daito-ryu. Beyond those technical considerations, what I truly care about is the culture, history and human interactions that those budo carry. It is fantastic to discover one’s place on the Aiki tree. The only way to do this is through the help of many men and women who are on that same tree. It gave me a sense of belonging to something very special and much bigger than myself.

About the author

About the author

Grigoris Miliaresis has been practicing Japanese martial arts since 1986. He has dan grades in judo, aikido and iaido and has translated in Greek over 30 martial arts’ books including Jigoro Kano’s “Kodokan Judo”, Yagyu Munenori’s “The Life-Giving Sword”, Miyamoto Musashi’s “Book of Five Rings”, Takuan Shoho’s “The Unfettered Mind” and Donn Draeger’s “Martial Arts and Ways of Japan” trilogy. Since 2007 his practice has been exclusively in classic schools: Tenshin Buko-ryu Heiho under Ellis Amdur in Greece and Kent Sorensen in Japan and, since 2016, Ono-ha Itto-ryu under 17th headmaster Sasamori Takemi and 18th headmaster Yabuki Yuji.

http://about.me/grigorismiliaresis