Christian Tissier’s Aikido Journey: In the Footsteps of a Master

In a previous issue of Hiden, I wrote about Frenchman André Nocquet Sensei, who was the first foreign uchi deshi of Ueshiba Morihei, and highlighted the major role that he had in the early promotion of Aikido in Japan and abroad. Even though I started in Nocquet Sensei’s group, he was already very old so it was another Frenchman, Christian Tissier Sensei, who actually inspired me to go to Japan. A generation after Nocquet, Tissier also gave up everything to go study with the masters at the Aikikai Headquarters. Now an 8th dan Aikikai shihan, he has become one of the most prominent promoters of the art in the world and a role model to thousands of aikidoka.

Christian Tissier was born in Paris in 1951. He practiced some Judo as a child and then started Aikido in 1962 under Nakazono Masahiro Sensei, a former uchi deshi of Ueshiba Morihei who had relocated in France. A very talented student, Tissier received his nidan from Nakazono Sensei in 1968. The year after, he decided to travel to Japan for six months in order to perfect his Aikido at the Aikikai Hombu Dojo.

Life in Tokyo was difficult initially but Tissier secured a steady income and a visa by teaching French at Gyōsei Gakuen and at the French Institute. As one of the few foreigners present at the time, he also had the opportunity to do some modelling. Tissier wanted to integrate and interact with Japanese society so he enrolled at Sophia University to study Japanese.

Tissier as a teacher at Gyōsei Gakuen (1970).

Compared to Paris, Tokyo seemed like a big countryside village. Small streets, no tall buildings… I liked that rhythm of quiet life and training, and also the fact that it was easy to connect with Japanese people.

When he arrived in Japan, Tissier was barely 18 and quite sure of himself, but he soon realized that he had to open up his mind if he wanted to appreciate the value of what was taught at Hombu.

I didn’t understand and didn’t like Hombu’s Aikido because it did not look like what I had learnt in France. It took me some time to realize that my views were incorrect.

Once he realized that it would take him a lot more than six months to start understanding Aikido, Tissier extended his stay and made sure to attend all the classes at Hombu, where and took ukemi for all the teachers. He befriended many teachers and sumikomi shidoin of the time, including Saotome Mitsugi, Masuda Seijuro, Endo Seishiro, Suganuma Morito, or Yasuno Masatoshi. Later, when Miyamoto Tsuruzo and Shibata Ichiro entered the Aikikai, they became known for their powerful practice and Tissier was one of the few westerners who was able to match their intensity.

Christian Tissier and Miyamoto Tsuruzo practicing in the right corner at the back of the dojo, which is still popular today for people who enjoy intense practice.

Tissier lived near the Hombu Dojo and participated in many of its activities. He was appointed dojo kanji by Masuda Sensei and he became responsible for helping and guiding foreign students. He organized meetings between them and Doshu about twice a year and he was also in charge of the foreigner’s demonstrations during the All Japan Demonstration at Hibiya Hall.

Christian Tissier demonstrating at Hibiya Town Hall during the All Japan aikido Demonstration in presence of the French ambassador (June 1975).

Tissier developed a close relationship with second Doshu Ueshiba Kisshomaru and Yamaguchi Seigo Sensei, for both of whom he served extensively as uke during classes and demonstrations.

Tissier with Ueshiba Kisshomaru at the Aikikai Hombu Dojo

I followed Doshu’s classes every morning and little by little, he started to take me as uke and became my Sensei. I was the same age as his son, Ueshiba Moriteru, so we often practiced together.

In private, Christian often talks about Kisshomaru Sensei and it is him who made me realize that it was thanks to the lifetime effort of Kisshomaru Sensei that we can all enjoy Aikido today around the world.

My best memory of Aikido is also the worst. Doshu was very ill and bedridden but he invited me to his house to give me the 7th dan personally. My son and I spent an hour with him and his son, Moriteru. It’s a beautiful memory because it came from him, but it’s also very sad because I knew that I would never see him again.

From Doshu, Tissier learned strong basics and technical precision. From Yamaguchi Sensei, he got a sense of freedom and his undeniable panache. He reckons that his relationship with them extended far beyond technique.

Yamaguchi Sensei was like a father to me, I used to go to his house and he took care of me.

Christian Tissier practicing with Ueshiba Moriteru under the watchful eye of Yamaguchi Seigo Sensei.

Even though Tissier followed Yamaguchi Sensei very closely, he admits that his Aikido does not resemble that of his teacher.

Yamaguchi Sensei didn’t like it when people tried to copy him. He would probably have been unhappy if I had become his clone.

Unlike what people sometimes think, Tissier does not encourage his students to copy him either. For many years, I tried to emulate his technique, with little success, and the first time that he gave me some praise was when I started to do things that suited my own body instead of copying him.

The outside form of the technique can vary, it is the core principles that must never change.

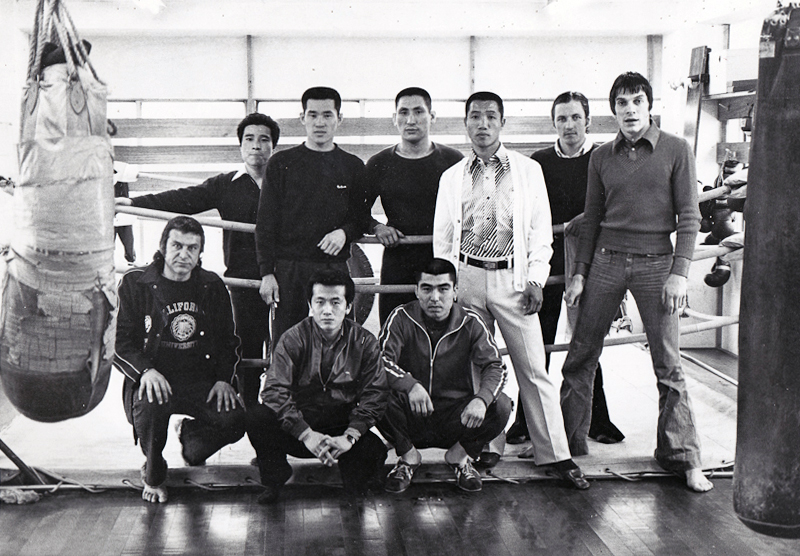

This focus on principles perhaps comes from the fact that Tissier experienced many other martial arts than Aikido. Notably, he practiced kickboxing at the legendary Mejiro Gym, which allowed him to understand the mechanics and timing of punches and kicks. He also learned Kenjutsu at the Seiseikan from Inaba Minoru Sensei, which gave his Aikido its sharp and cutting-like characteristics.

Christian Tissier at the Mejiro Gym with Shima Mitsuo and Fujiwara Toshio (1970).

What interests me most is being able to practice with people whose codes are different from mine and to make it work. That is why I like to practice with people I don’t know: beginners, tall people, big people, karateka, judoka, etc.

Once Tissier got promoted to fourth dan, Yamaguchi Sensei told him that he should return home to teach what he had learnt at Hombu. He returned to Paris in July 1976 and started his own school, “Le Cercle Christian Tissier”, which has become one of the most prominent martial arts schools in Europe.

Le Cercle Christian Tissier in Paris

In 1983, Tissier founded the “Fédération Française d’Aïkido, Aïkibudo et Affinitaires” (FFAAA), which was officially recognized by the Aikikai Foundation and is the representative for France within the International Aikido Federation (IAF). It is now the largest aikido group in France with over 26,000 practitioners.

Tissier was soon invited to teach seminars outside of France and he now has dedicated students all over the world. However, unlike other teachers, he did not want to set up an international organization.

There is no Tissier line in terms of organization, I am a student of the Aikikai and I teach Aikikai Aikido.

As I got to know him better, I came to understand that Tissier prefers to foster personal relationships with each of his students. My relationship with him actually started when Cyril Lagrasta and I invited him to teach for the first time in in Ireland back in 2007. We were a relatively small organization and our resources were quite limited, but Tissier made some his own travel arrangements to come help us develop our school.

Christian Tissier teaching at University College Dublin in 2007 (uke: Guillaume Erard).

I don’t act like a big Sensei, I don’t ask people to serve me or carry my bag. If I can help, I try to do it, and I ask nothing in return.

Even after leaving Japan, Tissier made sure to keep strong ties with Hombu and he spent several months in Tokyo every year for many years. He also encourages many of his students to train at Hombu. When I first told him about my plans to move to Japan, he said that I should not hesitate and he gave some useful advice on how to behave in Japan and at Hombu Dojo, which still serve me today.

Today, we are as competent in Europe as in Japan, but we have very different teaching styles, so it’s important that we keep our connection so that we can keep learning from each other.

Tissier was one of the first foreigners to give Aikido seminars in Japan, notably those organized by Okamoto Yoko Shihan, who studied in Paris with him for several years. Tissier was also the first non-Japanese instructor to teach during an IAF Congress.

Christian Tissier teaching at the Kyoto Butokuden during the 2015 international seminar organized by Aikido Kyoto (uke: Guillaume Erard).

Most French people of my generation discovered Aikido by watching Christian Tissier on one of his frequent TV appearances, notably the yearly demonstrations at the Martial Arts Festival in Paris Bercy. Tissier also authored many technical books and DVDs, which served as reference for generations of practitioners.

A few of Christian Tissier’s Aikido books.

Tissier defines Aikido as a system of education that grounds itself in martial techniques. Though he makes sure to focus on precise technique at first, Tissier also includes philosophical and moral components during his classes and insists that his students must grow as individuals.

One of the aims of Aikido is to remove fear. During an Aikido class, we should remove the situations of exclusion, refusal and non-communication. Wanting to become stronger than everybody else is meaningless.

Tissier was appointed by Ueshiba Moriteru Doshu as a member of the Senior Council of the IAF and he regularly supports activities such as the Congresses, the Combat Games, and most recently the Martial Arts Masterships held in Korea. I was actually part of the IAF team that went to Korea and I remember being incredibly nervous before my demonstration, not because of the cameras, but because I did not want to disappoint Tissier Sensei, who had helped us prepare all morning, and who was watching from the back.

Christian Tissier teaching during the 2019 Chungju World Martial Arts Masterships in Korea (uke: Guillaume Erard)

In July 2012, Christian Tissier was awarded the Foreign Minister’s Commendation by his excellency Komatsu Ichiro, the ambassador of Japan in France, to acknowledge his outstanding contribution to the promotion of friendship between Japan and Europe.

Christian Tissier receiving the Foreign Minister’s Commendation (2012)

Tissier was also invited as a guest of honor during the visit of Japanese Prime minister Abe Shinzo to France in 2014.

Dinner at Elysée Palace in honor of Shinzo Abe, Prime Minister of Japan (2014). From left to right: Abe Shinzo, Francois Hollande, Abe Akie, Christian Tissier.

On the 9th of January 2016, Christian Tissier was awarded the 8th Dan by Ueshiba Moriteru Doshu during the Kagamibiraki ceremony, at the same time as Miyamoto Tsuruzo Shihan and Kimura Jiro Shihan.

Christian Tissier receiving his 8th dan certificate from Ueshiba Moriteru Doshu during the Kagamibiraki (2016)

After the ceremony, I asked him how he felt about being an 8th dan, he told me:

It is the same grade as that of my own masters, so I take it with a lot of humility and gratitude towards Doshu. Inside me however, I still feel like the kid I was when I first came to Hombu. I’m still a kid who loves Aikido!

What keeps surprising me about Tissier Sensei is that in spite of the number of classes and seminars he has taught, the number of demonstrations he has given, I have never seen him display any extent of a blasé attitude about any part of his role. When some great teachers tend to rest in their zone of comfort, technically speaking, Tissier researches constantly, tests things, and even asks questions. I would argue that more than anything, it is this genuine passion that got him to where he is today.

This curiosity should not be mistaken with false humility, and even though he never forces it upon people, Tissier knows his rank and his role.

Humility is not to say “I’m humble.” Humility is to know exactly what you are, no more, but also no less.

I once had a discussion with his about the meaning of the title of shihan, he said this:

A shihan is not only a senior instructor, it ought to be a role model, not only technically, but also as a human being.

About the author

Guillaume Erard

Guillaume Erard is an author and educator, permanent resident of Japan. He has been training for over ten years at the Aikikai Headquarters in Tokyo, where he received the 6th Dan from Aikido Doshu Moriteru Ueshiba. He studied with some of the world’s leading Aikido instructors, including several direct students of O Sensei, and has produced a number of well regarded video interviews with them. Guillaume now heads the Yokohama AikiDojo and he regularly travels back to Europe to give lectures and seminars. Guillaume also holds the title of 5th Dan in Daito-ryu aiki-jujutsu and serves as Deputy Secretary for International Affairs of the Shikoku Headquarters. He is passionate about science and education, and he holds a PhD in Molecular Biology. Guillaume’s work can be accessed through his website and on his YouTube channel.