A Journey of Drawing the Bow, and Piercing the Self

Experiencing Kyudo as a Way of Human Cultivation, Reached by the “Bow Saint” Awa Kenzo, in Ishinomaki, Tohoku

Many foreigners who develop a deep interest in Japanese kyudo or Zen eventually arrive at a single book:

Zen in the Art of Archery by the German philosopher Eugen Herrigel.

What is described there is a state of shooting that cannot be fully grasped through Western rationalism alone—

“hitting the target without aiming at the target.”

The kyudo master who embodied this philosophy and transmitted it to the world was Awa Kenzo (1880–1939).

And the place where his journey began is Ishinomaki, in Miyagi Prefecture.

Awa Kenzo(1880 – 1939)

Why Was Awa Kenzo Called the “Bow Saint”?

Awa Kenzo began practicing kyudo at the age of 21—hardly an early start by traditional standards.

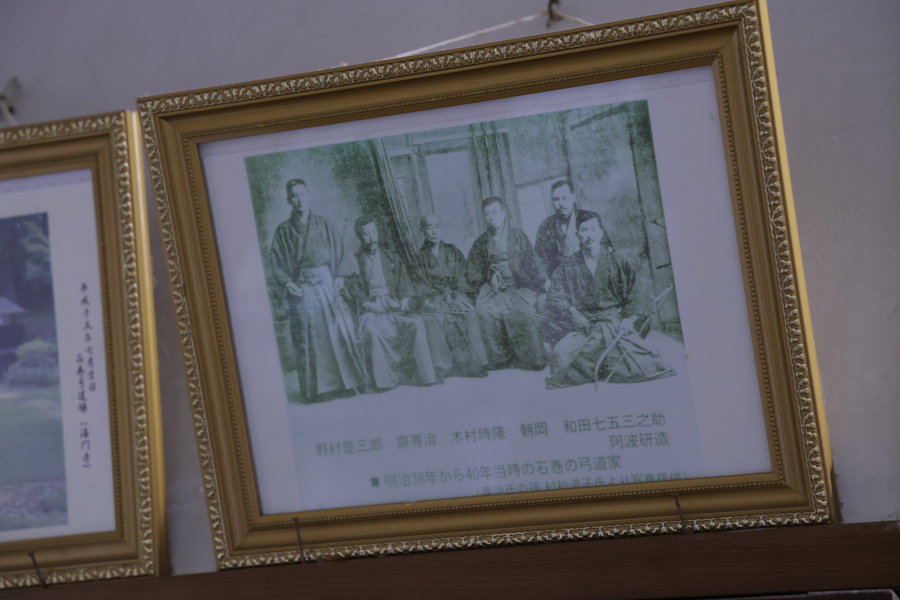

Kyudo practitioners in Ishinomaki during the Meiji period (1905–1907) (Awa Kenzō is seated at the far right of the front row)

Yet only two years later, at 23, he received full transmission (menkyo kaiden) of the Heki-ryu Sekka-ha school.

At 30, he became a disciple of Honda Toshizane, regarded as the foremost archer of his era, and by 33 had also mastered the Heki-ryu Bishu Chikurin-ha tradition.

In modern terms, this would be equivalent to completing two full lineages within the short span from late adolescence to early adulthood—an achievement impossible without extraordinary talent and relentless discipline.

However, this was not the end of Awa Kenzo’s greatness.

At the age of 43, he reflected on his own path with these words:

I have studied kyudo for over twenty years, yet only recently have I realized that I pursued form alone and forgot its spirit.”

Having reached the pinnacle of hitting the target, Awa recognized its limitations.

He decisively turned away from mere technique, shifting from kyujutsu to shado—from skill to a way of human cultivation.

Behind this transformation lay the influence of Jigoro Kano’s reformulation of jujutsu into judo as an educational and moral discipline.

Awa Kenzo was the one who embodied this movement within the world of archery—its true pioneer.

The principles he articulated—

“Issha Zetsumei” (One Shot, Absolute Commitment)

and

“Shari Kensho” (Seeing One’s True Nature Through the Shot)

were not abstract spiritual slogans.

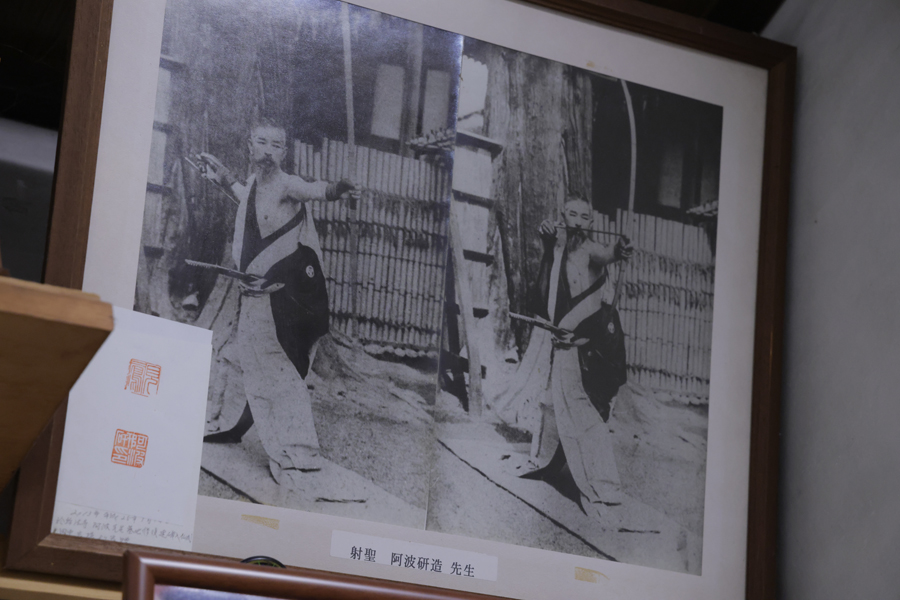

Awa Kenzo

They expressed a practice in which one stakes one’s entire being on a single shot, and within that moment glimpses one’s true self— discipline that polishes the human being through the bow itself.

Tracing the Way of the Bow: Tohoku as a Martial Landscape

Kyudo is not merely a traditional sport.

It is a rare cultural inheritance that preserves a worldview from before combat, prayer, and nature were separated.

That original landscape remains most vividly alive in Tohoku.

Across the region, ritual horseback archery (yabusame) is still performed today at shrines such as Osaki Hachimangu and Shiogama Shrine.

Arrows released from a galloping horse are offered before the deities.

In yabusame, shooting is not competition.

Hitting the target is a result, not the essence.

Minamoto no Yoshiie, The Illustrated Scroll of the Former Nine Years’ War (Important Cultural Property, National Museum of Japanese History)

The archer releases the arrow to inquire into divine will.

This worldview—where martial practice and sacred ritual remain inseparable—deeply resonates with the spiritual kyudo that Awa Kenzo sought.

Tohoku is also rich with legends of the bow.

One famous tale tells of Minamoto no Yoshiie (Hachimantaro), whose long-distance arrow is said to have flown tens of kilometers.

Its memory survives even today in the place name Yazuki.

Whether history or myth is beside the point.

What matters is that the bow stood at the very center of people’s imagination and spiritual life.

In Tohoku, the bow was at once a symbol of power, an instrument of prayer, and a vessel of story.

A Narrative Kyudo Experience Found Only in Ishinomaki

In this land of mountains and sea, where people have long lived in close dialogue with a harsh natural environment, the bow was never merely a weapon—it was a means of connecting heaven and humanity.

Since the great turning point of 2011, following the Great East Japan Earthquake, Ishinomaki has continued to rebuild itself, carrying both history and hope forward.

Ishinomaki, the birthplace of Awa Kenzo, faces the Sanriku Sea—one of the world’s three great fishing grounds—and is also home to the Ishinomori Manga Museum, celebrating Shotaro Ishinomori, creator of Cyborg 009 and Kamen Rider.

Within this unique setting, the tour program(Learn the Spirit of Zen through Kyudo ~Experience “Zen in the Art of Archery” Tour~) offered here is far more than an activity.

It begins by visiting places associated with Awa Kenzo—walking in his footsteps, quietly remembering his life and work.

Through films and commentary, participants encounter his philosophy and biography, then stand before his grave, engaging with him across time.

Because of this introduction, the act of drawing the bow that follows becomes not a mere experience, but a meaningful practice.

Ishinomaki remains a living place of kyudo.

The grave, the dojo, the stories passed down—and even the collapse and reconstruction after the earthquake—all testify that kyudo is not a museum artifact, but a spiritual culture sustained by human hands.

To draw the bow here is not to reenact the past, but to step into an unbroken continuum.

Practical Training: Different Paths of Learning

The kyudo practice in this tour takes place at a dojo closely associated with Awa Kenzo.

Beginners wear authentic kyudo attire and carefully learn basic etiquette, posture, and breathing through close-range practice.

special mini-seminar led by Mr. Ken Kurosu

Experienced practitioners participate in joint training with members of the Ishinomaki Kyudo Association, and attend a special mini-seminar led by Mr. Ken Kurosu, of the Date Insei-ha Kyujutsu Research Group.

Striking the target is difficult.

Yet what matters here is not hitting, but cultivating a body and mind from which a natural release emerges.

This is not merely archery practice—it is an encounter with the profound world of kyudo and Zen.

Why not experience for yourself the state that Eugen Herrigel glimpsed here over a century ago?

Returning to Everyday Life Through the Bow

The aim of this experience is not enlightenment.

It is to bring the insights gained through kyudo back into daily life.

Focus and release.

Correctness and naturalness.

These principles extend far beyond the dojo, into work and life itself.

To draw the bow is to pierce the self.

A single day in Ishinomaki may become a quiet yet profound turning point for those who take part.

~Experience “Zen in the Art of Archery” Tour~

~Experience “Zen in the Art of Archery” Tour~