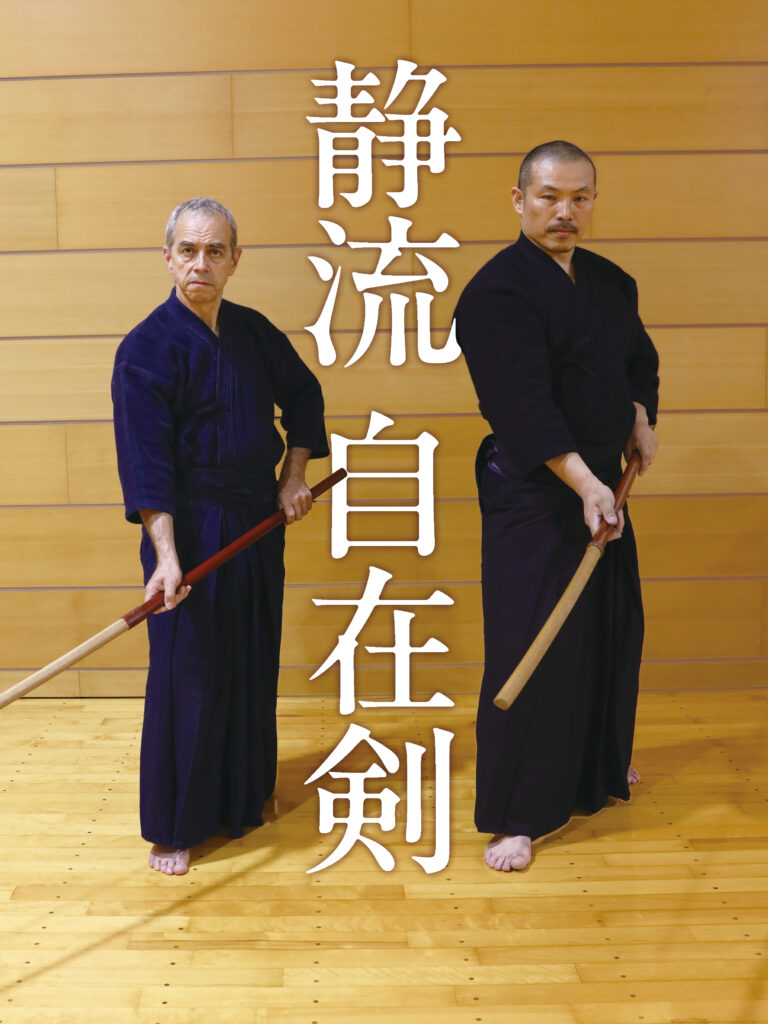

Sword of Freedom: The Case of Shizuka-ryu’s Jizaiken

Text by Grigoris Miliaresis

“My school, called Buko-ryu, was originally a nagamakijutsu school but since that is the same as a naginata, we teach it as naginatajutsu. Because it was originally about the nagamaki, there may be some differences from the naginata; however, because these differences aren’t specified, I will speak of it as if it was a naginata.” These are the words of Yazawa Isao, the 16th-generation head of Tenshin Buko-ryu heiho, the naginata school I have been practicing for the last 18 years. This nagamaki connection has been one of the most intriguing aspects of our tradition and while its previous heads decided that our interpretation of the nagamaki is not the usual where the weapon is a sword with a very long tsuka/hilt but an 8-shaku (2.4m/8ft) naginata, bigger than our regular 7-shaku (2.1m/7ft) one, I have always wondered how the traditional nagamaki handles.

Do nagamaki still exist? Just ask Shunpukan

To the best of my knowledge, there is only one school that teaches nagamaki today; it is Shizuka-ryu which doesn’t call it “nagamaki” but “jizaiken” (自在剣), a fascinating term, especially in a world as fraught with rules, regulations and restrictions as Japanese budo, meaning something like “unrestrained sword” or “versatile sword” or, if you want to be poetic about it “sword of freedom”. The reason the weapon is named thus though is much closer to the first two renderings: being something between a sword and a naginata, this is a weapon that gives its wielder the benefits of both and it could be as effective against a sword as it could against a naginata. And to make things even more interesting, in her same essay, Yazawa sensei also mentions that among the naginata traditions she was able to examine at that time (early Meiji period) Shizuka-ryu was the oldest.

Exciting as the idea of submerging into the depths of naginata traditions of the Edo Period (and most probably before it since the days where the naginata and the nagamaki were battlefield weapons of choice were during the Kamakura Period) might be, my primary interest is the handling of the weapon. And to do that I had to turn again to the Kanto branch of the Shunpukan and Akabane Daisuke sensei; like the previous time with Yagyu Shinkage-ryu he was very welcoming and since the curriculum of their Shizuka-ryu jizaiken consists of just five kata, called Joryaku, Churyaku, Geryaku, Saryaku and Uryaku which could translate respectively as High Tactic, Middle Tactic, Low Tactic, Left Tactic and Right Tactic, he would be willing to show them all to me, with the assistance of the dojo’s other shihan, Wakao Yoko.

The Shunpukan’s Shizuka-ryu comes from the dojo’s first instructor, Kambe Kinshichi (1894-1980): it has been part of his family’s history and is said to have originated with Minamoto no Yoshitsune (1159-1189) who taught it to his mistress Shizuka Gozen (1165-1211) and this is where it gets its name from. This connection to Kamakura made Akabane sensei’s teacher, and second head of the Nagoya Shunpukan, Kato Isao (1933-2022) to think that the Kanto Shunpukan had a special connection with Shizuka-ryu and it was his wish that it would be the one preserving it. Within the Shunpukan, these five jizaiken versus jizaiken kata were traditionally taught to female members for whom the dojo’s Owarikan-ryu spear practice might have been a little too rough (different times, different standards!) but of course today they are taught to all members and provide an excellent way to expand their study of Yagyu Shinkage-ryu.

Wakao Yoko shihan, Grigoris Miliaresis, Akabane Daisuke shihan

The jizaiken: first impressions and basics

Before going into the kata, we went over the jizaiken’s basic footwork, kamae and suburi with Wakao sensei; being a walking instructor she is a specialist when it comes to correct body posture. Having to do these basics with a weapon that is 162 cm (5.3 ft) long where the top 70 cm (2.3 ft) are the blade and the bottom 92 cm (3 ft) the haft, my first impression was actually negative: it felt too long for a sword and too short for a naginata and this was compounded by the facts that the triangular geometry of the blade didn’t match the sensation you have when using either a sword or a naginata, that it was very thin (didn’t have a caliper but I would guess the oval cross-section of the haft was something like 3.5 x 2.5 cm i.e. 1.4 x 1”) and that the haft was lacquered with matte urushi, the traditional Japanese lacquer, that made it very sticky!

But of course these things are only to be expected when one is trying a new weapon. Thankfully the basics – when in chudan kamae holding the weapon in a way that protects your own center line, anchoring the weapon with the back hand on the waist, tilting the blade a little to the side, keeping the body in hanmi- are very close to those that can be found in most budo; the same goes for the basic suburi that raises the jizaiken parallel over the head with the two hands getting close and brings it down cutting to chudan level with the back hand sliding to the end of the haft, where the ishizuki, the butt-end of the weapon. This suburi is performed from both sides with the hands changing place when they are over the head and when we did it several times and I got somewhat acquainted with the weapon and its length, we moved on to the five basic kamae each of which appear in the five kata.

First there is jodan kamae where the jizaiken is diagonally over the head, with the left fist at forehead level and the right arm open to the side (the kissaki points to the upper right and the ishizuki to the lower left). Then there is chudan, which we already mentioned above, with the right hand forward and the kissaki pointing at the opponent’s left chest and then gedan where the weapon is lowered from chudan and the blade is turned completely to the side. For the fourth kamae, just named “hidari no kamae” i.e. “left stance”, we bring the jizaiken vertical in front of the left side of the chest with the left hand on the waist and the blade looking forward and for the fifth, called, “migi no kamae” (right stance), we take a step back with the right foot and open the jizaiken in front of our lower body and to the right tilting its kissaki to the ground and little to the back –the body remains turned forward.

Suburi with Wakao shihan

Five basic kamae

The kata: Joryaku, Churyaku, Geryaku, Saryaku and Uryaku

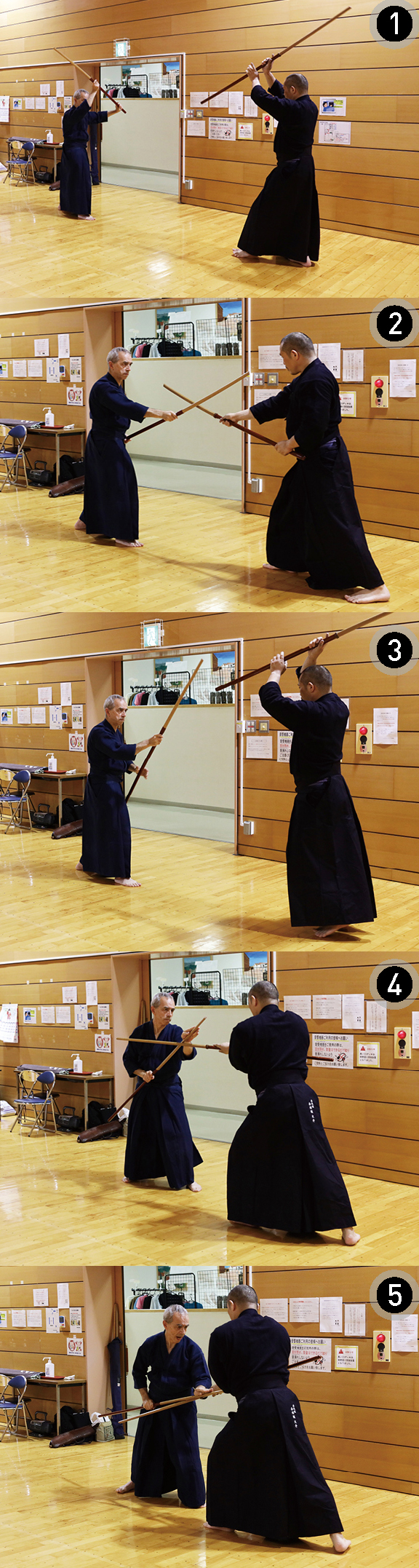

Having gone over the kamae, Wakao sensei changed places with Akabane sensei and we dove right in the first kata, Joryaku. Both shidachi and uchidachi start from gedan and then uchidachi goes to chudan and shidachi to jodan. Uchidachi goes towards shidachi aiming for his right hand. When he attacks, shidachi strikes uchidachi’s jizaiken down and uchidachi brings the weapon over his head, crosses hands and attacks shidachi’s right side of the neck which shidachi blocks bringing his right palm to the back of the blade and holding the jizaiken vertical. From there he pushes with his blade the blade of uchidachi down and steps in for a tsuki accompanied by a kiai. From there, they disengage, cross weapons at a distance where their kissaki cross, go to gedan and from there take three steps back to their initial position.

Joryaku

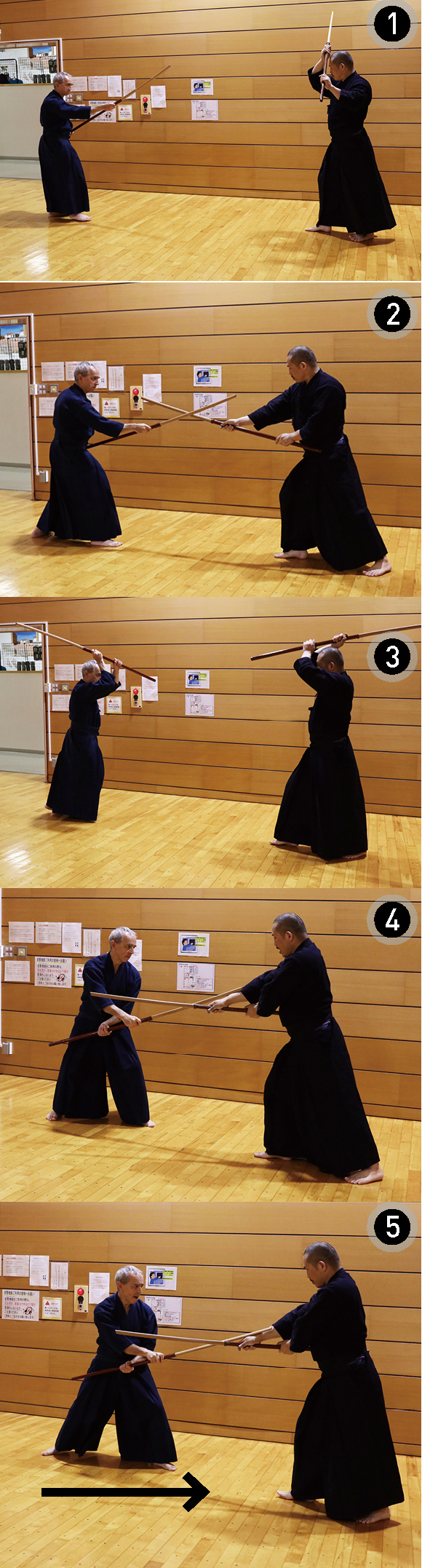

In the second kata, Churyaku, uchidachi is in jodan and shidachi in chudan and walk towards each other until they get to striking range. Uchidachi attacks shidachi’s front (right) hand and shidachi blocks with a compact cut staying in chudan. Uchidachi takes a small step back, raises the weapon over his head, crosses hands and again attacks shidachi’s right hand but from the outer/ura side. Here shidachi pulls a little backdoes a full, 360-degree twirling of his weapon and with crossed hands attacks himself uchidachi’s front/right hand. Here there is no final tsuki but uchidachi takes one step back and shidachi follows, pressuring him, again with a kiai. And from there, they disengage in the same way.

Churyaku

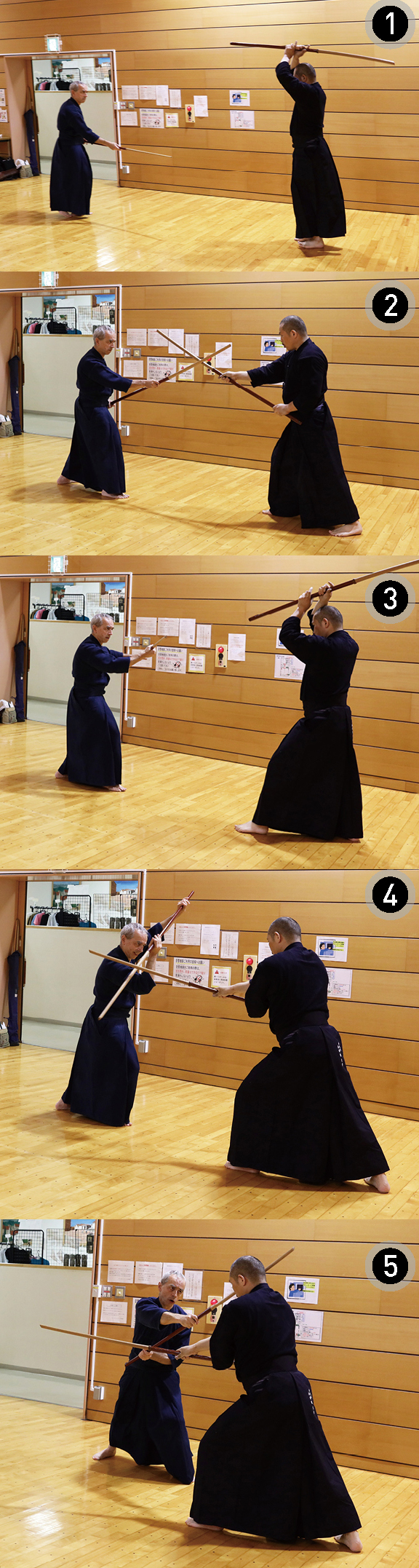

Then comes Geryaku that has uchidachi in chudan and shidachi in gedan. Hre too they both walk towards each other and at striking range, uchidachi strikes men/head which shidachi blocks raising his jizaiken from gedan to a kamae higher than chudan. Like in Churyaku, raises his hands over his head, crosses them, goes a little out to his left and attacks shidachi’s right side but this time at the waist. Here shidachi performs a special block which reminds Yagyu Shinkage-ryu’s Enpi where he brings the jizaiken parallel to and in front of his face and for a moment with its blade resting horizontally on his right open elbow and from there he turns it over his head, goes out to the left and with arms crossed attacks uchidachi’s neck with a nagashi uchi strike and a kiai before they disengage.

Geryaku

Number four is Saryaku where uchidachi is in chudan and shidachi in hidari. Uchidachi walks towards shidachi to attack his right hand and like in Joryaku, shidachi strikes uchidachi’s weapon down. Uchidachi steps back in a kamae that resembles a regular kenjutsu/kendo jodan but with his jizaiken held almost parallel to the floor and shidachi follows him doing a full twirl of his weapon and changing hands as if going for a rising cut (kiriage), similar to the one we worked on in our Yagyu Shinkage-ryu article (Yagyu Shinkage-ryu: In the Shadow of the Sword). Uchidachi goes out to the right to attack shidachi’s waist and shidachi responds by pulling back, doing an overhead change of hands and cutting down on uchidachi’s front/right hand with a kiai as they both kneel, finish and disengage –again, this echoes of Yagyu Shinkage-ryu.

Saryaku

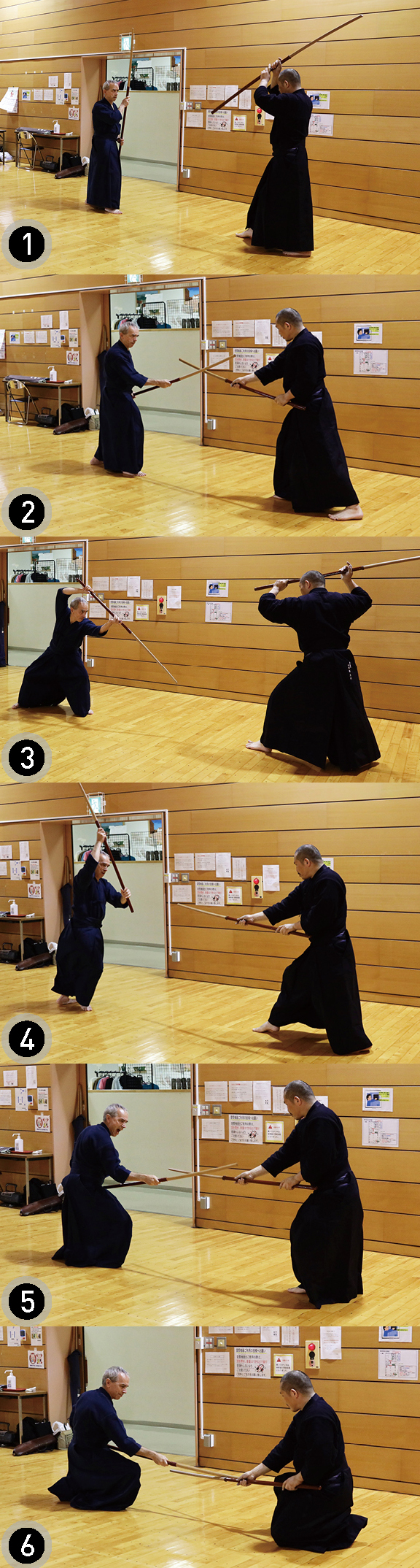

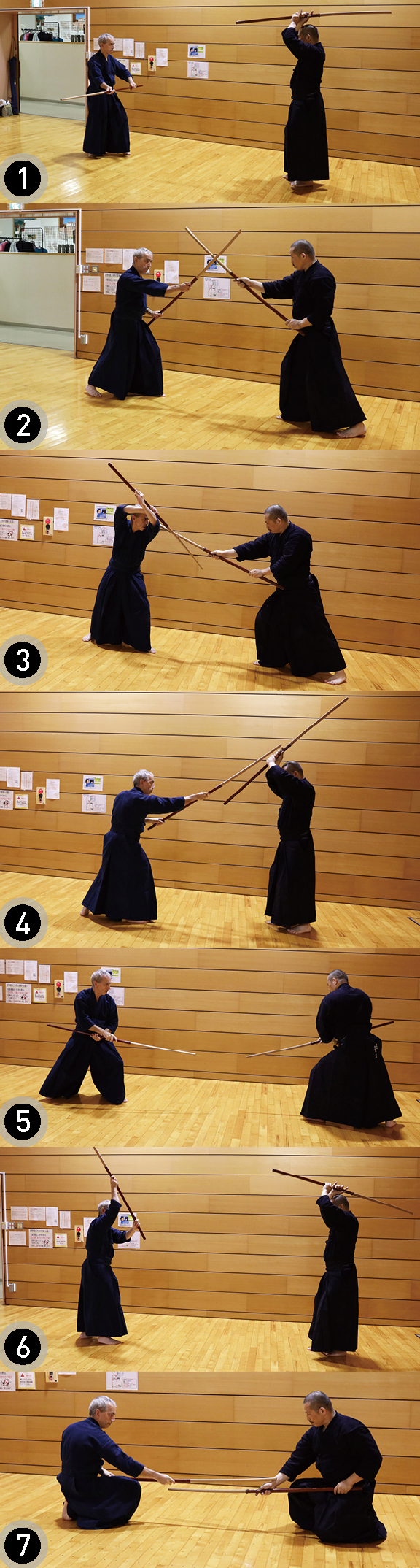

The last kata is Uryaku and starts with uchidachi again in chudan and shidachi in migi walking towards each other. Uchidachi raises his jizaiken overhead and cuts down but shidachi brings his jizaiken to the front and blocks uchidachi’s attack with his feet still in the migi position i.e. left foot forward. Uchidachi tries the same thing again but this time shidachi brings the right foot forward and deflects the incoming blade to the left ending with his weapon in a modified hidari kamae with the jizaiken held higher. As uchidachi pulls back to repeat his overhead movement once more, shidachi steps in with his left foot forward, and with hands crossed, cuts at uchidachi’s right forearm. Uchidachi steps back with his right foot and with his hands crossed, cuts high at shidachi but shidachi deflects to the right and then steps in with his right foot and as uchidachi raises his hands over his head, shidachi cuts his left arm -in a reversal of the previous movement. Uchidachi responds by taking one step forward with his left foot and doing himself a cross-hand cut at shidachi’s right waist which shidachi blocks with Geryaku’s uke nagashi block and as uchidachi steps back and raises his hands over his head, shidachi moves in to cut his right forearm. Uchidachi steps in and cuts at shidachi’s left waist but mirroring the previous movement, shidachi does an uke nagashi but at the left side, changes hands over his head, steps in with his right foot and as uchidachi once again raises his hands overhead, cuts uchidachi’s left forearm. Last, they both open the distance a little, take a wide, cross-hand gedan kamae, bring the jizaiken overhead and do a mutual cut while kneeling with shidachi cutting first uchidachi’s right/front hand. And then disengage.

Uryaku

Thoughts on weapons familiar and unknown

Are just five kata enough to explore all the possibilities of a weapon? Obviously not but Shizuka-ryu’s set is very well thought out and covers enough of those possibilities to create the reflexes that will help the practitioner respond even to situations that are not contained in the kata. When you get to Uryaku, the most complicated of the set, you review everything you have done so far and by working methodically to build accuracy and speed, you get to a point where you can utilize what the jizaiken has to offer and truly use it as you please; there were several points during our work together when Akabane sensei pointed out that the way the hands move along the weapon is not set in stone and the practitioner freely adjusts and customizes it to their own body and preference.

Does the jizaiken live up to its promise of bridging the gap between a sword and a naginata? Up to a certain point it does: especially if someone comes to it from a naginata, it allows transferring the body and hand placement and movements, but having a shorter haft, it allows better leverage and consequently the delivery of techniques that are surprisingly strong compared to those of a sword but way more accurate than they would be if performed with a naginata. So yes, it is a weapon definitely worth adding to your repertory although if I were to choose I would go for something with a little more body: my ideal jizaiken would be a cross section of about 5 x 3 cm (2 x 1.2”) for the haft and with a blade to match. And perhaps some day I will have one made and try to see how it would work with my Buko-ryu kata.

But this isn’t about Buko-ryu, it’s about Shizuka-ryu and having now a reasonably good idea of the Shunpukan, I can see how the jizaiken can stand on its own but at the same time, also connect organically with the dojo’s main study, Yagyu Shinkage-ryu, broadening the horizons of its sword fighters and revealing possibilities they might not have considered. It certainly gave me some new insights regarding the dimensions of weapons and how they influence body mechanics and execution of techniques and for this I had to thank once again Akabane sensei and Wakao sensei for their time, their detailed and clear teaching style and their willingness to share with us this important part of their legacy.

Grigoris Miliaresis