“The Sword and the Chrysanthemum” by Paul Martin Part1: What is a Japanese sword?

Text by Paul Martin

Paul Martin and his Kamon(Photo/Steve Morin)

Each installment of this series is available for a limited time only—don’t miss it!

(Publication period: October 14, 2025 – November 13, 2025)

Part1. What is a Japanese sword?

The Mythical Origins of the Japanese Sword

We begin this series of articles on Japanese swords by first asking. “What is a Japanese sword?” What at first may seem like a simple question and answer becomes increasingly complex when you try to explain about Japanese swords in their entirety.

The perfected curved Japanese sword is thought to have appeared around the mid 10th-11 C. However, in order to gain a better understanding of Japan and its relationship with the sword, we have to go back to the very beginning to gain an understanding of the spiritual roots of Japanese swords which can be seen in the origin myths of Japan: The Kojiki and the Nihon Shoki. According to these myths, the islands of Japan were formed by the deities, Izanagi (male) and Izanami (female). Izanagi dipped a heavenly jeweled spear into the Sea of Japan and stirred the brine. Then, some droplets of mud fell from the tip of his spear forming the islands of Japan (the third of which was Okinoshima, Shimane prefecture). The important points about this tale is that spears and swords were objects of the gods, and that the spear brought life to Japan.

Painting by Eitaku Kobayashi showing Izanami and Izanagi consolidating the land with the spear “Ama-no-Nuboko”

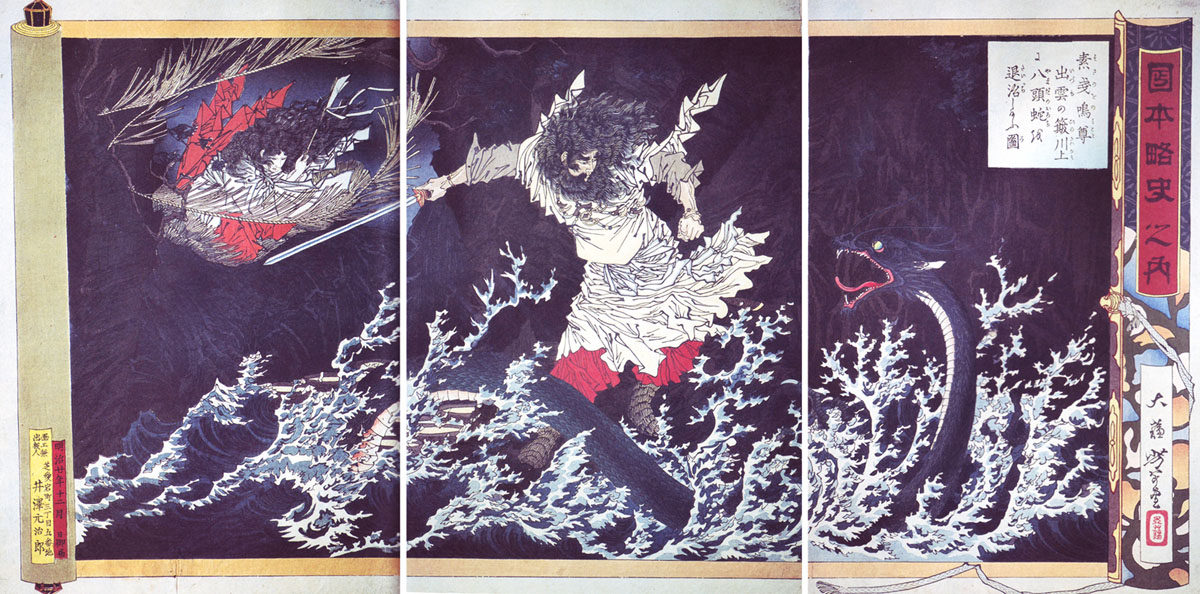

Susanoo-no-Mikoto and Kusanagi-no-Tsurugi

Izanagi and Izanami went on to have several children, but the most famous of these are, Amaterasu-Omikami: the sun goddess and patron deity of Japan, and her brother, Susanoo-no-mikoto. Susanoo was eventually banished to earth for upsetting the lands of Japan and distressing his sister Amaterasu. While roaming around the plains of Izumo (modern Shimane prefecture) he came across and old couple with their daughter, Kushinada-hime, crying. When he enquired as to why, they told him that the eight-headed, eight-tailed serpent dragon, Yamata-no-Orochi, had come every year and taken one of their daughters. He was due to come again, and they were down to their last daughter.

Painting by Tsukioka-Yoshitoshi showing Susanoo no Mikoto slays the 8 – headed serpent Yamata-no-Orochi upstream of the river at Hirokawa in Izumo Province.

Susanno told them that if they gave him their daughters hand in marriage, that he would slay Yamata-no-Orochi. To which they readily agreed. He requested them to make eight casks of sacred sake (rice wine) and place them in the path of the serpent-dragon. The Orochi came along and it’s eight-heads drank out of the eight casks. Once it had gotten very drunk, Susanoo attacked, and entered into a fierce battle with the Orochi. He eventually cut off all eight of its heads. However, when he cut into one of the tails, he chipped his sword. On inspection, he discovered a sword. This sword was known as, the heavenly gathering of clouds sword (Murakumo-no-Tsurugi). He took this sword and gave it to Amaterasu in repentance for his bad deeds. Later, Amaterasu gave this sword to her grandson Ninigi-no-Mikoto, along with the sacred jewels (Yasakami-no-Magatama), and sacred bronze mirror (Yata-no-Kagami) when he was sent from heaven to rule the earth. In turn, Ninigi gave these three sacred items to his great-grandson, Jimmu, who become the first official emperor of Japan. The three items became the symbols of the divine right to rule in the form of the three sacred treasures of the imperial regalia.

Yamato Takeru and His Sword Kusunagi (Yamato Takeru no mikoto, Kusanagi no tsurugi), from the series Gekkô’s Miscellany (Gekkô Zuihitsu)

The Murokumo-no Tsurugi was originally housed in Japan’s largest shrine, Ise shrine. Around the 3rd C. another hero, Prince Yamato Takeru appears. Takeru is sent on a mission to quell the disobedient peoples of eastern Japan. He borrowed the Murakumo sword from his aunt, Yamato-hime, who was the High-Priestess of the shrine. While on his mission, he was lured into the long grass, and the enemy set fire to the grass to kill Takeru. He used the sword to cut down the long grass around him and save his own life. What’s more, according to some versions of the story, the wind blew in the direction that he pointed the sword, so he relit the fire and blew it back towards his enemies. From this point onwards, the sword became known as, the grass-cutting sword (Kusanagi-no-Tsurugi). However, what is most important about this story is that it is the oldest story of a sword protecting its owner’s life.

Loss and Transmission

Takeru went on another mission to fight with an evil deity of Mt. ibuki, but did not take the sword with him. He was subsequently made sick by the deity and died. Takeru’s wife took the sword to where he died, and Atsuta Shrine was constructed, where the sword has been said to be housed until this day. However, another common story takes place in 1185 when the Taira family absconded from Kyoto, taking the child emperor, Antoku, and the imperial regalia with them. In the final battle of the Genpei War between the Minamoto and Taira clans at Dan-no-ura in 1185, the Taira were defeated by the Minamoto. Emperor Antoku’s grandmother, Tokiko, told him to pray to the east, and while he did, she tucked the imperial jewels into the folds of her kimono and the sword into her belt. She then took the 7-year-old Antoku in her arms and jumped overboard. They were never seen again. It is said that the imperial jewels miraculously floated to the surface and were saved, but that the sword was lost.

the Three Sacred Treasures (Mirror, Sword and Jewels) by 菊竹若狭 (Kikutake Wakasa)

As for the jewels, many things of value in Japan are kept in paulownia wooden boxes. So, this means that if the imperial jewels had been in a wooden box, then it is entirely possible that they could have floated to the surface. On the other hand, according to the Jinno-Shotoki (A Chronicle of Gods and Sovereigns), by Kitabatake Chikafusa, the sword that was lost at Dan-no-ura was not the Kusanagi-no-tsurugi, but another special sword used by emperors to carry around on a daily basis. He states that the Kusanagi-no-Tsurugi never actually left Atsuta Shrine. Furthermore, around the early 18th C., priest at the shrine, Matsuoka, and his colleagues opened the recepticle containing the Kusanagi-no-Tsurugi when cleaning the shrine. It was described to be in a stone box packed with red clay, inside which was a wooden box. Inside the wooden box was a hollowed out, gold leaf lined camphor log. It became quite a scandal, as they had opened the box and viewed the sacred sword directly. Matsuoka and the head priest were banished to other shrines, while some of his fellow priests who also saw the sword died of mysterious illnesses. Matsuoka’s description of the blade matches that of a double-edged bronze sword. This too, is within the realms of possibility, as if Yamato Takeru had borrowed an ancient sword from Ise Shrine in the 3rd C., this would be without a doubt a bronze sword.

Atsuta Shrine

According to tradition, the three imperial items are passed from emperor to emperor as a symbol of their succession. Even in 2019, when the current emperor was enthroned as the Emperor Reiwa, there are various photographs of him during various ceremonies where there are two boxes accompanying him. The scared mirror is said to remain in the imperial shrine. However, the large square box that is said to contain the imperial jewels, the other is a long narrow box that is said the contain the Kusanagi-no Tsurugi. It is at this point that I would like to remind the readers that this is the sword that was claimed to have been discovered in the tail of an eight-headed, eight-tailed serpent dragon. Therefore, Japanese mythology and real history are inextricable. It is this from this spiritual background that swords in Japan became revered as sacred objects. Blades have been devoted to the deities of Japan since the Yayoi period (800 BC-300 CE). Many ancient votive iron blades were discovered on top of Mt. Nantai by Lake Chuzenji, Tochigi prefecture.

The Symbolism and Natural Beauty of the Japanese Sword

In any case, swords in Japan are not merely weapons, but can be an instrument of enlightenment, a spiritually protective talisman (omamori-gatana). There are tales of swords healing the sick, or being used as an implement for performing exorcisms, or even as a vessel in which for the gods to reside. The sword is also a symbol of status. It may represent the right to rule, or the warrior class, but it is also a symbol of responsibility: by which it may have become the object with which you were duty bound to ritually take your own life. It is also your spiritual guide and most unforgiving sensei in your pursuit of Japanese sword arts. Additionally, Japanese swords are also sublime art objects. Of course, a sword must be functional (not bend, not break and cut well), but also meet the requirements of being intrinsically beautiful. An aspect that coincides with the Japanese appreciation of nature.

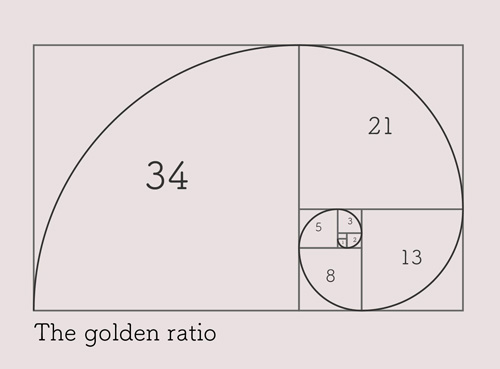

The curved shape of the perfected Japanese sword appears to be very natural and aligns with the Fibonacci sequence (Golden ratio). The various changes in the shape (curvature and geometry) in the Japanese sword throughout history reflect the period in which they were produced in. The center of curvature may change slightly from period to period, but no matter which period, the curvature retains a natural appearance. There are no odd shapes. The surface pattern of the steel (hada, or Ji-hada) comes in four basic types. However, yet again, these surface pattern reflect elements of nature. They appear much like the wood grain pattern in planks of wood, and all have names that relate to nature. The pattern of the hardened edge is called a hamon. It is a transitional line of metallurgical crystals between the very hard steel of the cutting-edge, and the softer back of the blade. These hamon and various crystalline activities within it, come in a wide range of types that all have nature related terminology. In the peaceful Edo period, a ranking based on cutting ability was devised (Wazamono, Owazamono, etc), but all of the descriptive terminology for Japanese swords is very romantic. There are no super human killing crystal descriptions, only poetic notions of drifting sands (sunagashi), leaves (yo), lightning (inazuma), and so on.

Paul Martin appreciating a Japanese sword.

The Eternal Japanese Sword

The Japanese sword and its spiritual roots are the backbone of Japanese culture. This is proven by the ability to connect the sword many aspects of Japanese culture, such as the aforementioned mythical origins. There are many ceremonies involving swords and conversely, the implements of esoteric Buddhism are often made as decorative carvings into blades. Tea ceremony houses even today have a katana stand at the entrance to leave your sword. Performance arts such as Kagura is used to convey the Shinwa, or mythology of Japan, but also often feature swords in Kenbu, or sword dances. Noh, and particularly Kyogen performances such as, Awataguchi, and, Nagamitsu, that are humorous stories based upon the names of famous makers. Even today, many phrases used in modern Japanese society have their roots in Japanese swords, such as ‘sori ga awanai’ (our curvatures do not align) This used for someone you do not get along with. As each sword and scabbard are custom made, a sword will not fit into another’s scabbard because the curvatures will not align. Shinogi wo Kezuru refers to the loss of steel from the sides of a sword from heavy use in battle. It now means that you have worked/fought very hard. Moto no saya ni osamaru, means let’s stop fighting and put our swords back in our scabbards. The sword is entwined into the cultural fabric of Japan.

The Grand Kagura (Daidaikagura) preserved at Musashi Mitake Shrine in Ōme City, Tokyo. The photo shows the masked dance “Slaying the Great Serpent.”

However, even in Japan, some people when they see a real Japanese sword say, “Osoroshii!” (terrifying). Yet, these same people use large kitchen knives to cut flesh to prepare food. So, what is the difference? I think that there maybe two reasons for this. One, the Japanese sword is considered a mirror to your own soul. Two, it is imbued with the spiritual power of the gods of Japan and it is the sense of that immense power that can be misconstrued as terrifying. The history of Japanese swords spans over a thousand years. The craft has faced various challenges in its history, the introduction of the gun, the modernization of Japan in the Meiji era. However, no matter how close to the craft of the Japanese sword comes to extinction, as long as there is a Japan, there will always be a Japanese sword. It is the embodiment of the soul and sensibilities of the Japanese people. To gain an understanding of the sword of Japan, is one of the fastest routes to understanding Japanese culture.

Mr. Martin practicing Iaido at the Noma Dōjō. He has also trained in many other Japanese martial arts, including Kendo and Karate.