What’s Weird About Japanese Budo & Bujutsu Culture Abroad?

Text by Osano Jun(International Suigetsujuku Bujutsu Association)

Introduction

It has been over thirty years since I began teaching Budo(Japanese martial arts) overseas. During that time, I have witnessed many misconceptions about Japanese martial arts in foreign countries. These misconceptions largely stem from the fact that Japanese Budo are being transmitted in a manner that deviates significantly from common sense. There are two primary causes for this.

The first is the incorrect instruction and dissemination of misinformation by Japanese masters. The second is the misinterpretation of Japanese Budo by local practitioners, which has been widely spread through various media. However, Japanese masters who fail to correct these misconceptions also bear significant responsibility.

Dojo Names

Until the Meiji era, the word dojo commonly referred to a place for Buddhist training. Places for martial arts(Budo & Bujutsu) training were called keikoba, embujo, or bukan. Here, we use the modern and commonly accepted term dojo.

Traditionally, dojo names included characters like “館” (kan), “塾” (juku), or “堂” (do). Among these, “館” is the most commonly used. However, in Europe, most dojos are referred to as “〇〇 Dojo.” The problem lies in the “〇〇” part, which is often inappropriate—sometimes using names of animals, fish, or even insects. It ends up sounding like a zoo. For example, a former Romanian branch of ours had a “Yamabushi(Mountain Samurai) Dojo.” I advised changing the name, but they insisted a Japanese kendo teacher had named it. Perhaps it was meant to be a training hall for yamabushi, but as a matter of common sense, there are no samurai in the mountains. If the Japanese involved had any cultural sense, they would have offered proper guidance.

“Genbu,” along with Byakko, Suzaku, and Seiryū, is one of the four guardian deities that protect the cardinal directions of the world. As the guardian of the northern heavens, Genbu is depicted as a tortoise entwined with a serpent. Revered also as a god of war, Genbu is a fitting symbol for a dojo bearing the name of Hokushin Itto-ryu, which includes ‘Hokushin’—referring to the North Star—in its title.

Some exemplary and historically significant dojo names include:

- Genbukan 玄武館 (Hokushin Itto-ryu): “Genbu” refers to the celestial guardian of the north.

- Renbukan 練武館 (Shinto Munen-ryu): “Renbu” means cultivating martial technique.

- Shigakukan 士学館 (Kyoshin Myochi-ryu): “Shigaku” refers to acquiring a samurai’s education.

- Koshikan 傚士館 (Maniwa Nen-ryu): “Koshi” means to emulate and learn the way of the samurai.

- Yobukan 燿武館 (Kogen Itto-ryu): “Yobu” means to shine through martial learning.

The Kogen Itto-ryu dojo “Yobukan” (top photo) and the (Maniwa) Nen-ryu dojo “Koshikan” (bottom photo) both preserve the traditional architectural style of nagayamon gatehouses. These historic training halls are valuable cultural assets and have been designated as Important Cultural Properties.

These names express an ideal image of humanity or philosophical symbolism. In contrast, European dojo names include:

- Rooster Dojo 雄鶏道場 – a chicken farm

- Hummingbird Dojo 蜂鳥道場 – an aviary

- Mountain Samurai Dojo 山武士道場 – a samurai hut turned bandit hideout

- Hagakure Dojo 葉隠道場 – an execution ground teaching seppuku

- Asahi Dojo アサヒ道場 – a beer garden run by a brewery

- Cobra Dojo コブラ道場 – an Indian-style pet shop for cobras

These are all actual dojo names. While common in Europe, such naming is less prevalent in the U.S. or U.K. Why do Japanese instructors allow this? Teaching only techniques is insufficient—passing on Japanese Budo as culture is the true responsibility of instructors.

The root of the problem is the confusion between “kan” and “dojo.” “Kan” is the name given to a dojo (building), whereas “dojo” simply means a place of practice. Therefore, proper use of 〇〇 Dojo should include the martial art style, the location, or the instructor’s surname, such as:

- Karate Dojo, Kendo Dojo, Jujutsu Dojo

- Tokyo Dojo, Osaka Dojo, Nagoya Dojo

- Sato Dojo, Tanaka Dojo, Watanabe Dojo

These make sense to Japanese people who intuitively understand these distinctions and would never choose names like “Cobra Dojo.”

Keikogi (Training Uniforms)

The generic term for Budo attire is keikogi, but due to the sportification of (Budo)martial arts, terms like judogi, kendogi, or karategi are used today. Overseas, keikogi is often incorrectly referred to as “gi.” These misnomers must be corrected.

In classical martial arts(Koryu Bujutsu), which are traditional samurai arts, even beginners must wear hakama. From the moment of entry, proper attire must be emphasized. Any instructor who says “ordinary exercise clothes are fine at first” is unqualified.

Also, in Koryu Bujutsu, one must distinguish between keikogi and embugi (demonstration attire). Except under special conditions (e.g., summer heat), performing embu in keikogi is unacceptable. Attire and behavior during embu must follow tradition. Even in sumo, the belt used during tournaments (silk mawashi) is clearly distinguished from that used in training (cotton mawashi).

Both images depict practitioners of the Nakazawa-ryu Goshinjutsu system. The upper photo shows the standard keikogi (training uniform) worn during regular practice, while the lower photo shows the formal attire used for public demonstrations—complete with hachimaki (headband) and tasuki (cords used to tie up the sleeves). In classical martial arts (koryu bujutsu), there has traditionally been a strict distinction between everyday kata training attire and the formal dress used for official public embu (demonstrations).

I once witnessed a demonstration in Europe where students from a classical style performed iai in karate uniforms with kaku obi belts—an uncomfortable sight. Even in Japan, recent demonstrations often neglect traditional attire such as tasuki, hachimaki, or correct momodachi stance. If such practices are not transmitted, the art is fundamentally flawed.

Also concerning is the practice of leaving keikogi at the dojo. In a European aikido dojo, I saw keikogi hanging from the ceiling—a custom copied from certain Japanese dojos. Keikogi should be taken home and kept clean. Sweaty, dirty uniforms are not only unhygienic but offensive to others.

Etiquette (Rei)

It is customary to bow when entering and leaving the dojo—this is standard in all martial arts. However, respect toward others is often lacking. The most problematic is the use of “OSS.” While I have no intention of lecturing those who use this in karate, our association strictly forbids it. There is no tradition of such a greeting in Japanese Budo, and I find it quite disrespectful.

Greetings like “Konnichiwa,” “Onegai shimasu,” “Arigatou gozaimasu,” or “Shitsurei shimasu” are more appropriate and commonly used in Japanese society.

Training Equipment

In classical martial arts(Koryu Bujutsu), training tools must be crafted and used in accordance with each style’s traditions. Using mass-produced equipment is unacceptable. Because of inadequate transmission, many styles have lost their traditional equipment specifications. It is not convincing when those claiming legitimacy use store-bought bokuto.

In Europe, people often use mass-produced bokuto or staffs without permission. Instructors must firmly teach that each style has its own appropriate tools. For iaito as well, each style has set measurements. At a recent European seminar, many brought short staffs made of non-oak wood for jojutsu—they were sternly warned. Incorrect dimensions prevent proper execution of techniques.

These tools should ideally be sourced from Japan, though custom production is now difficult. Nonetheless, procuring them individually is essential.

Training implements used in Tendō-ryū Heihō. All of them are crafted in accordance with the school’s formal specifications.

Demonstrations (Embu)

Sport Budo have tournaments where practitioners can assess their skill level. But classical martial arts(Koryu Bujutsu) abroad have no such matches, and thus, no opportunities to showcase acquired techniques.

In Japan and China, there are traditional embu to dedicate performances to the gods, but such customs do not exist in the West. Our association rarely holds embu. Yet Budo are samurai disciplines and also art forms—demonstrating acquired skills gives them meaning.

Even without hōnō embu, public demonstrations can and should be held. Japanese instructors, including those in our association, should create such opportunities. In the Edo period, the highlight of a samurai’s year was performing in front of their lord—a great honor and source of rewards.

Currently, this is the only regularly held official demonstration (joran embu) of its kind in Japan, conducted by the Matsushiro-han Bunbu Gakko Budokai. The review and inspection are overseen by Mr. Sanada Yukitoshi, the 14th head of the Matsushiro Sanada family.

Demonstrations dedicated to the kami (deities) at Shinto shrines are a traditional practice in Japan. Since most Western practitioners do not share the cultural custom of “offering techniques to the gods,” it is important to provide them with alternative forms of motivation—such as opportunities for public demonstrations.

Learning Japanese

Finally, I conclude by addressing the importance of Japanese language study for foreign practitioners. Those who aim to become Budo instructors abroad must learn Japanese alongside their training. Deep understanding of techniques and theories is impossible without it. Language contains nuances and sensibilities that cannot be conveyed through physical instruction alone. Many instructors realize that English fails to capture the essence.

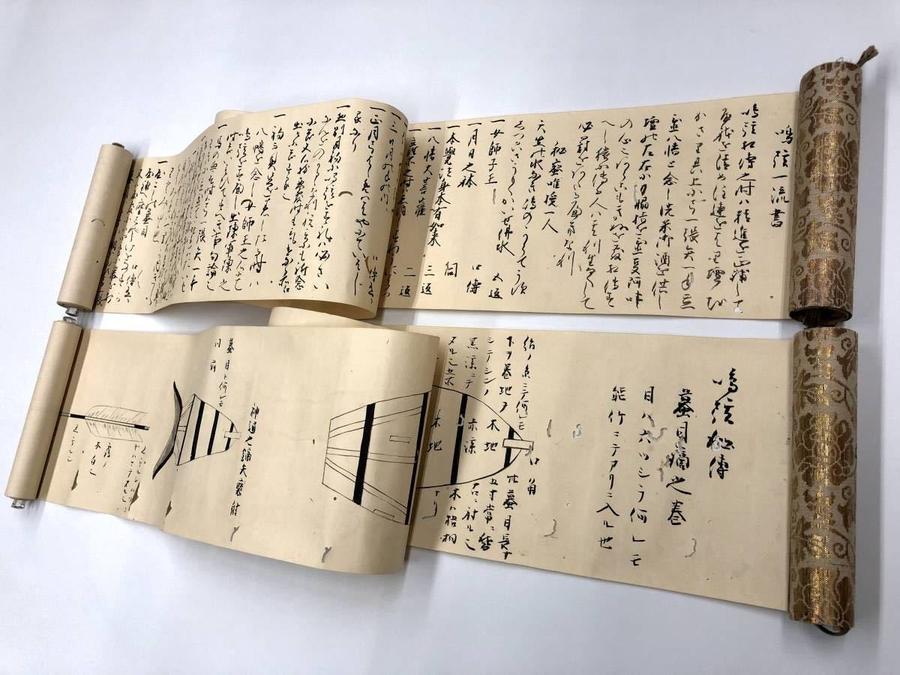

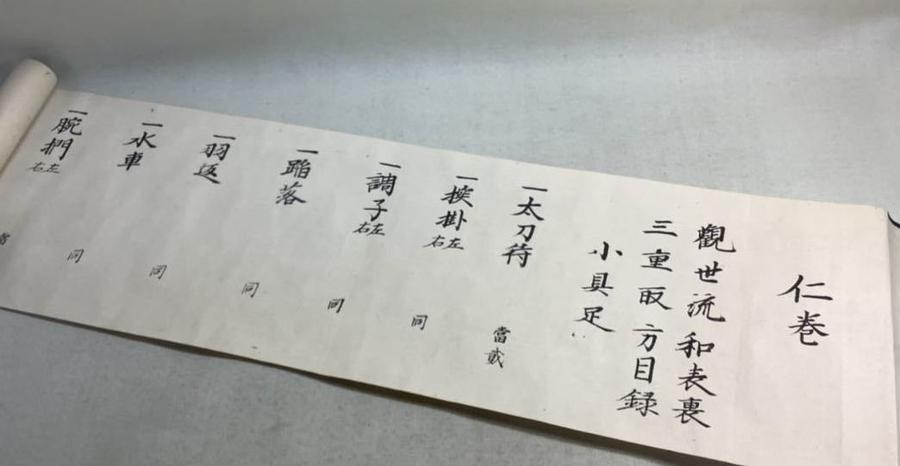

Even native Japanese struggle with ancient densho (transmission scrolls), so it is nearly impossible for foreigners to understand them without Japanese. However, if basic conversational skills are acquired, deeper understanding is possible. Budo have specific terminology and teachings; the names of forms have meanings that cannot be conveyed without knowledge of Japanese language and culture.

To fully inherit a classical martial tradition, one must also be able to read and interpret the traditional scrolls (densho).

Saying “I can’t do it” and giving up means one will never fully understand or master Budo. Instead, we must encourage them: “If you can’t, then strive until you can.”

Even if they may seem old-fashioned today, the names of kata in classical martial arts carry deep meaning.