Sword saints past and present: a visit to Shinto Munen-ryu’s Yushinkan

Text by Grigoris Miliaresis

Ogawa Takeshi Shihan

“So, do you want to be deceived?” asked the teacher the student that stood before him asking to join his school. The student replied “Yes, let’s get deceived” and that was the beginning of a relationship between, then 69-year old Nakayama Zendo, 8th head of the Edo Den/Kanto-ha lineage of Shinto Munen-ryu and the Yushinkan dojo and then 24-year old Takeshi Ogawa, the 10th and present head. What was the deception? That the student would dedicate his life to the ryu; 54 years later, the answer can be seen in every major koryu budo event where the now 78-old sword master is leading the Yushinkan delegation in some of the most intense demonstrations to be seen, carrying apparently effortlessly the weight of his tradition.

The road to Nakayama Hakudo

Negishi Shingoro

And what a weight this is! Starting in the mid-Edo Period with Fukui Hyoemon Yoshihira (1700-1782) from Shimotsuke Province (present-day Tochigi Prefecture), his study and mastering of Shin-Shinkage Ichien-ryu, his musa-shugyo ascetic practice around Japan, his enlightenment at the Iizuna Jinja shrine in Nagano dedicated to the tengu-like deity Iizuna Gongen that led to the creation of Shinto Munen-ryu and his Edo dojo which four generations later and under Saito Yakuro (1798-1871) became Renpeikan, one of the Edo’s three greatest dojo, the school entered the modern period with a legacy that most schools would envy. But what would follow would make this legacy even bigger, because it would involve one of the most influential swordsmen of the Meiji period, Negishi Shingoro (1844–1913) and the closest the 20th century has to a “sword saint”, Nakayama Hakudo (1872-1958).

Nakayama Hakudo

It was Negishi, the 6th head of Shinto Munen-ryu who transformed the Renpeikan to the Yushinkan in 1885 and who contributed significantly to cementing the relationship between the police force and swordsmanship (as a gekiken and iai teacher to its members) and in creating modern kendo as part of the Dai Nippon Butokukai committee who developed the Dai Nippon Teikoku Kendo Kata, the predecessor to the present-day Nippon Kendo Kata, the one who brought Shinto Munen-ryu in the 20th century. But it was his student, Nakayama Hakudo 7th head of the school, founder of Muso Shinden-ryu, first triple hanshi (of kendo, iaido and jodo) from the Butokukai, heir to the Yushinkan and allegedly teacher of two-thirds of Butokukai’s top kendoka, the one who managed to keep it alive through the hardships of the pre-WWII, WWII and post-WWII periods and to leave it to the hands of his son, Nakayama Zendo (1900-1981), one of the few people who inherited Hakudo’s martial knowledge in its totaliy. The same Nakayama Zendo who in 1969 would ask Ogawa Takeshi to give his life for this heritage.

Nakayama Hakudo and Nakayama Zendo

Shinto Munen-ryu had been on my radar since I read the story of Nakayama Hakudo, over 30 years ago. But I got hooked when I saw it demonstrated by Ogawa-sensei and the members of the Yushinkan: with a good balance between kenjutsu and iai and with the kenjutsu part stripped of fancy moves and done at real distances with intent and intensity, there’s little doubt in my mind that Shinto Munen-ryu as performed today and filtered through some of the best swordsmen Japan has produced in the last 150 years, all of whom also practiced gekiken and/or kendo, is very close to the school that was considered one of Edo’s finest. This was a school I definitely had to see from up close!

First things first

As I often do in these experience articles, I asked Ogawa-sensei to show me Shinto Munen-ryu’s kumitachi and iai first kata; that way I could have an idea of what beginners in the school have to face. But before kata comes suburi i.e. solo practice, so we started with two that are part of Yushinkan’s warm-up routine. Sensei said that these can be thought of as variations of kendo’s haya-suburi where the practitioner continuously strikes men stepping quickly (essentially hopping) forward and backward but in Shinto Munen-ryu the targets in the first exercise are do (trunk) and kote (forearm) and in the second, nodo (throat) and kote –in the second exercise, the nodo attack is with a one-handed thrust (katate-tsuki), much like kendo’s tsuki attack.

Suburi 1-1

Suburi 1-2

Suburi 1-3

Suburi 1-4

Suburi 2-1

Suburi 2-2

Suburi 2-3

Suburi 2-4

After a few repetitions, we moved to Ipponme from the Shoden Kumitachi set. Here, the opponents start from a chudan (middle) stance, then go to gedan (low stance) and approach each other until they reach an issoku-itto no ma i.e. when their sword tips touch. Shidachi steps back and takes a jodan (high) stance and uchidachi steps forward threatening shidachi’s exposed left wrist. From there, shidachi using his full weight drops his sword on uchidachi’s (this is called “uchiotoshi”) lifts his right foot and stepping/stomping forward and thrusts uchidachi’s exposed suigetsu (solar plexus); these two movements are performed in rapid succession, essentially in one beat, with shidachi not allowing uchidachi any time or space to react. After uchidachi has been defeated, both opponents bring their swords with a big, swirling motion around their left shoulders to chudan and from there they disengage.

Ipponme from Shoden Kumitachi 1

Ipponme from Shoden Kumitachi 2

Ipponme from Shoden Kumitachi 3

Ipponme from Shoden Kumitachi 4

Ipponme from Shoden Kumitachi 5

Like Ono-ha Itto-ryu’s Hitotsu-gachi, the first kata the student learns and a container for the school’s essential principle, kiriotoshi, Shinto Munen-ryu’s Shoden Ipponme is deceptively easy. The hardest thing to grasp is, of course, the timing between the uchiotoshi and the tsuki (thrust) that ends the confrontation but the truth is that the uchiotoshi itself was quite hard. To make it work in the way Shinto Munen-ryu wants it to, you need to turn the blade to the left so you will strike the opponent’s blade with your blade’s shinogi (ridge) but on impact you also have to slide your blade towards his tsuba (hand guard) and, most importantly to follow through all the way and fight the instinct to stop after the two swords have clashed. All that while raising your right foot to and moving on to the final tsuki.

Uchiotoshi

Suihei-tsuki

And second

One of the things that I have always found intriguing in Shinto Munen-ryu, is the frequency in which a block with the left hand on the swords mine (spine) appears in its curriculum; this is quite common in Shinkage-ryu-derivative schools but I believe it’s more prominent in this ryu. Justifying it as a way to get inside the opponent’s vital space and therefore escaping his striking range, as expressed per the old adage “under the sword is hell but get one step closer and it’s heaven”, Ogawa-sensei was kind enough to show me Nihonme, the second kata of the Shoden Kumitachi which is when Shinto Munen-ryu practitioners are introduced to the block.

Nihonme from Shoden Kumitachi 1

Nihonme from Shoden Kumitachi 2

Nihonme from Shoden Kumitachi 3

Nihonme from Shoden Kumitachi 4

Here, shidachi starts from hasso (sword to the side of the head) and uchidachi from chudan. They approach each other and at engagement distance, shidachi cuts left do to which uchidachi responds with an ukenagashi-like block to the side and immediately counterattacks with a shomen cut. Here shidachi brings his left hand to the top one-third of the blade and rests the its mine on the base of the thumb with the palm facing him and raises both arms so he blocks uchidachi’s shomen before it reaches his head. Uchidachi rapidly continues with a right do cut which shidachi blocks in the same way, stepping backwards and bringing his hands to his side, with his hands in the same position on the blade. From there, shidachi steps in, drops uchidachi’s sword to his side and back by pushing it with his sword’s shinogi and as this leaves uchidachi’s body in an open position, shidachi brings his sword in horizontal position and thrusts uchidachi’s right flank. Then, they open the distance, bring the swords to chudan with the same over-the-shoulder motion they did in Ipponme and disengage.

Handling the sword this way was perhaps the hardest part of this first taste of Shinto Munen-ryu: neither of the schools I practice has a technique like that so this was new territory for me and while I can block with a naginata or a bo, trying to do it with a much shorter weapon and especially one which decades of practice have ingrained the idea that it should be handled with both hands on the tsuka (hilt) proved to be extremely difficult. It was only after over an hour of repeated practice with Saito-san, one of the members of Yushinkan who where there to help us with this article, that I managed to do it in a semi-acceptable way and Ogawa-sensei’s comment about it allowing you to enter the opponent’s personal space and therefore offering a strategic advantage actually made sense.

Back to first –but solo

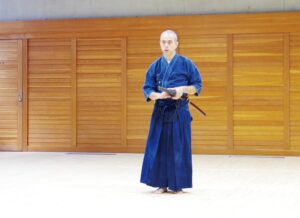

I had asked Ogawa-sensei for a taste of the other part of Shinto Munen-ryu’s curriculum i.e. iai and he graciously obliged by showing me a warm-up exercise called “Nuki-Osame Kihon” and Ipponme, the first kata from Shinto Munen-ryu’s standing iai curriculum (Tachi Iai Shoden). Despite Shinto Munen-ryu being famous for its standing iai kata, Nuki-Osame Kihon is performed from seiza and for those who are familiar with the 12 kata of All Japan Kendo Federation’s Iaido (aka Seitei Iaido aka Zenkenren Iaido), it is like two repetitions of the first kata, Ipponme Mae but without the forward movement: starting from seiza, you draw the sword cutting horizontally while stepping forward with the right foot, then you change feet and cut vertically, perform a yoko chiburi (shaking of the blood by moving the sword sideways) and noto (re-sheathing the sword), return to seiza and then going over the same thing once again but this time doing the horizontal cut on the left foot and the vertical on the right; of course, this sequence can be repeated as many times as you want since it is a good way for the practitioner to familiarize themselves with the basics of drawing, cutting and re-sheathing without worrying for extra movements.

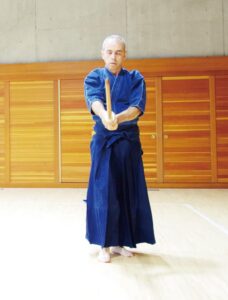

Tachi Iai Shoden 1

Tachi Iai Shoden 2

Tachi Iai Shoden 3

Tachi Iai Shoden 4

Tachi Iai Shoden 5

Tachi Iai Shoden 6

Tachi Iai Shoden 7

Tachi Iai Shoden 8

Tachi Iai Shoden 9

The really interesting part was, of course, the kata itself: from a shizentai (natural stance) you start moving forward and while drawing the sword and on the second step you cut horizontally at chest level, move one step backwards and cut vertically, then one step forward and cut again vertically, and immediately go to a kasumi no kamae stance where the sword is held parallel to the ground with the blade facing up and the two hands extended over the head and the body turned to the left. From there, with one more step forward, the body turns to the right and the hands trace a full circle and do an upward cut (kiriage) that ends with the tip of the sword facing diagonally up. This is where the action ends and begins the chiburi and noto sequence of Shinto Munen-ryu which is among the most idiosyncratic you can witness in the koryu world: the sword is brought almost vertically to the ground (ostensibly for the blood to drip), then brought to rest on the left shoulder, the right hand’s grip is reversed and the sword is pulled downwards so it’s mine slides on the shoulder while the left hand brings the saya (scabbard) to meet its tip. When it does, the sword is inserted in the saya with the hand always in reverse grip.

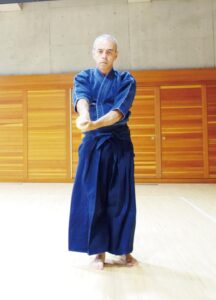

Tachi Iai Shoden 10

Tachi Iai Shoden 11

Tachi Iai Shoden 12

Tachi Iai Shoden 13

Over the years, I have collected several iai experiences, some while practicing Zenkenren Iaido and a little Muso Jikiden Eishin-ryu in Greece and abroad and some by trying various ryu mostly, but not exclusively, for these articles here in “Hiden”. I wouldn’t by any definition of the word think of myself as an expert and especially these days when my iaido practice is incidental and just for suburi, not unlike Shinto Munen-ryu’s aforementioned Nuki-Osame Kihon but since hardly a day goes by without spending at least a couple of hours with a sword I can say that Shinto Munen-ryu’s iai felt more spontaneous than many of the things I have done in the past. The movements are big but in a natural way and it’s easy to see how over the years, they give the practitioner a level of familiarity with the sword that will complement and augment their kenjutsu; who would expect anything less from the school once headed by the man who created one of the most popular styles of iai while being one of the country’s top kendoka?

Kiriage 1

Tachi Iai Shoden 2

Tachi Iai Shoden 4

Food for thought

The hours we got to spend with Ogawa-sensei and his students, Nakajima-san, Shirosaki-san, Saito-san and Takada-san passed real fast –too fast for dealing with a school with a curriculum of 90 kenjutsu kata and 79 iai kata. Still, and as a bonus, besides the kata that he showed me, Ogawa-sensei was kind enough to also demonstrate the Goka Gogyo, a set of five kata considered to be the vehicle for some of the school’s highest teachings; using the five cosmological elements of heaven, earth, man, yin and yang and correlating them with the five Confucian virtues of benevolence, justice, courtesy, wisdom and sincerity and the five basic stances of kenjutsu (jodan, gedan, chudan, in and yo), these kata are not scripts where uchidachi does X and shidachi responds with Y and wins but want to put the practitioner (who by that point has studied the biggest part of the curriculum) in a situation where they do not care anymore about winning or losing but for responding naturally and fluently to what their opponent does –it is saying something about the importance of this set for Shinto Munen-ryu that in its demonstrations, the school always opens with it, performed by Ogawa-sensei himself together with one of his most senior students.

Nihonme from Joden Kumitachi 1

Nihonme from Joden Kumitachi 2

Nihonme from Joden Kumitachi 3

Nihonme from Joden Kumitachi 4

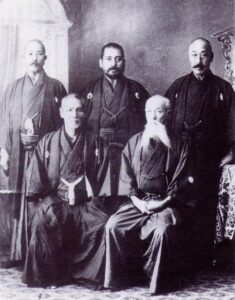

Negishi Shingoro (front row right), Naito Takaharu (back row center), Takano Sasaburo (back row left )

There were several things that Ogawa-sensei said during our visit that stuck with me. One is certainly his emphasis on “kankyu”, the alternation between fast and slow that makes the kata become alive. Or his insistence on “shinken shobu” i.e. “fighting for real” even when we were talking about present-day shinai kendo. Or that phrase from Shinto Munen-ryu’s Jun Menkyo license that goes “Our school is dedicated to change, and our goal is to learn from various schools, to extract the best of them and make them into a great success”; this is an admonition that the techniques and lessons taught by the teacher must be enhanced through the student’s own responsibility and practice, and that “the skill is in the person and not in the school” and it echoes the well-known story that because he had to judge practitioners from various schools, Nakayama Hakudo famously studied 50 schools after he had become THE Nakayama Hakudo.

Most probably though, what stuck most would be that story showing the dignity and character of two other 20th century sword saints, Hokushin Itto-ryu’s Naito Takaharu (1862-1929) and Ono-ha Itto-ryu’s Takano Sasaburo (1862-1950): at a Kyoto Butokuden kendo bout when an aiuchi (simultaneous strike) happened, Sasaburo striking men and Naito striking do, they both exclaimed “I’ve lost!” For Ogawa-sensei this level of integrity and confidence only comes after a lot of practice where every strategy and every technique is examined several moves ahead and always with the intensity of having to fight for your life, not just to win; it is this kind of ceaseless practice that makes the practitioner think until the last moment of their existence “mada tarinu”: still not enough.

Goka Gogyo

PS

This story wouldn’t had been possible without the cooperation and patience of Ogawa sensei’s students Messrs Nakajima, Shirosaki, Saito and Takada. Thank you all very much for this unforgettable experience.

Grigoris Miliaresis

About the writer

Grigoris Miliaresis has been practicing Japanese martial arts since 1986. He has dan grades in judo, aikido and iaido and has translated in Greek over 30 martial arts’ books including Jigoro Kano’s “Kodokan Judo”, Yagyu Munenori’s “The Life-Giving Sword”, Miyamoto Musashi’s “Book of Five Rings”, Takuan Shoho’s “The Unfettered Mind” and Donn Draeger’s “Martial Arts and Ways of Japan” trilogy. Since 2007 his practice has been exclusively in classic schools: Tenshin Buko-ryu Heiho under Ellis Amdur in Greece and Kent Sorensen in Japan and, since 2016, Ono-ha Itto-ryu under 17th headmaster Sasamori Takemi and 18th headmaster Yabuki Yuji.