Text by Grigoris A.Miliaresis

It must have been around 1977. I was only ten years old and my fascination with Japan was already going strong, with all the strength a child of 10 can muster and I was always pressuring my father to buy me any books related to it and its culture (I didn’t call it “culture” back then –it was just “anything about Japan”). Knowing that I was enthralled by the stories of an old war buddy of his, a war correspondent in the Korean War and one of Greece’s judo pioneers regarding the martial arts, one day he brought me 3 slim tomes from a series titled “Practical Karate” filled with pictures of a middle-aged rather plump Japanese and a big, tall Westerner showing self-defense applications of karate techniques; the two men were the books’ authors and they were Masatoshi Nakayama and Donn Draeger.

This was the first time I came across the name “Donn Draeger”; with time, I would see it again and again in English-language publications related to the martial arts of Japan. But it would take another 10 years until I discovered in a martial arts’ bookstore, the only one in Athens, the work that I later found out was considered by most his “magnum opus”: the trilogy Martial Arts And Ways Of Japan comprising of Classical Bujutsu, Classical Budo and Modern Bujutsu & Budo. Like most people outside Japan, this was my first exposure to a systematic chronicle about the martial arts ofJapan and their development from the times of the Hogen Monogatari and the Heike Monogatari to Shorinji Kempo, the most modern style recorded by the time the books were written (i.e. early 1970s). And like many people outside Japan, I was captivated.

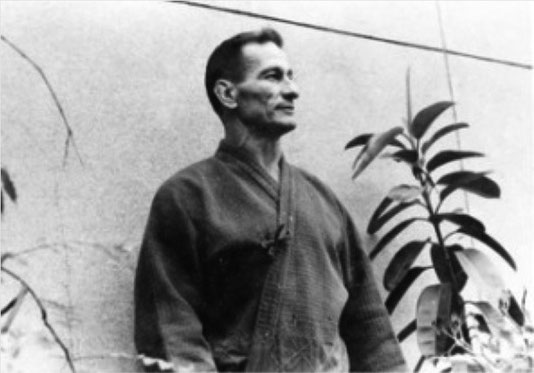

As captivating as his subjects were, was Draeger himself: he wrote with an authority displaying a knowledge of his subject far deeper than that of most academic researchers –and if those pictures of the “Practical Karate” books were any proof, it looked as if he had done some training himself so I knew I had to find out more (remember, this was pre-Internet and I was living in Greece so I believe I’m allowed some ignorance). So I started searching in books’ databases and libraries and martial arts magazines and slowly and painfully an amazing story started unfolding: this man was so much involved in pretty much everything related to the martial arts –and not only of Japan, even though he seemed to have specialized in those- that it was impossible to have trained in all of them to the extent and depth his writings suggested.

With time I came to realize that he had. Although he never went for the spotlight, others wrote about him –among them his friend and collaborator Robert W. Smith (1926-2011) an ex-marine, ex-CIA employer posted in Taiwan in the early 1960s, a prolific writer in the subject of Chinese martial arts and one of Tai-Chi’s most strong supporters and evangelists in the eastern US. Despite being very emotional (not to mention loquacious) in his writing –they were close friends, after all- his account of Draeger as narrated in his 1999 martial arts autobiography Martial Musings gives a quite detailed sketch of the man and his numerous accomplishments. And when I say “numerous” it is not a figure of speech: if it wasn’t for many eminent martial arts’ teachers and practitioners, Westerners and Japanese corroborating the facts, it would be hard to believe that one man could have done so much in just 30 years.

Sometime along the way the Internet came and access to information became much easier; in the meantime I had also developed a personal network of people who had lived or were still living in Japan so I had the opportunity to ask more about this remarkable man, Donn F. Draeger (this was how he signed most of his work and this is how he is usually mentioned in writing). And more begat more and with time I came to realize that there was little exaggeration when it came to Draeger’s life in the martial arts: he had indeed been there and done that –whatever “that” was. Moreover, he had done it well enough and earnestly enough to earn the respect of pretty much anyone who met him. In a world as subject to pettiness and small-mindedness as any, I have yet to hear one bad word for Donn F. Draeger.

When I came to Japan I started looking for him; not the man himself of course since he had been dead for over 25 years but for his footprints in bookstores, libraries and dojo. And while in the beginning I was astounded by the fact that there weren’t any, with time I came to realize that it made sense: by all accounts, Draeger was a very private person and really devoted to his work researching the martial arts and his training. His closest collaborators in his martial arts’ research were also foreigners who with time (before or after his death in 1982) had returned to their countries and even though most of them made sure to keep his memory alive in stories told to their students or in publications, online or paper (like Smith’s) he didn’t leave any students in Japan while the organization formed to function as a focal point for his research, the International Hoplology Society, was also based in the US.

So apparently little has been left of him in Japan, the country that was his home for half his life and to whose martial traditions he had dedicated his life. There are memories of him still surviving in the minds of some of the (now elderly) Japanese budoka who met him and trained with him in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s but not a record of his actual trip. This article as well as the one that will follow in a future issue is an attempt to collect some of these memories and introduce to a younger generation of Japanese this really important man.

Donald Frederick Draeger was born on April 15, 1922 in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. He started training in Yoshin-ryu jujutsu when he was a child but moved on to Kodokan judo reaching 4th dan by 1948, when he was 26 years old. In the meantime he had entered the United States Marine Corps where he served from 1943 until 1956. His first unit, the Corps Signal Battalion participated in the battle of Iwo Jima and was supposed to be part of the troops that would invade Japan; after August 1945 and Japan’s surrender, his unit was sent to North China to accept the surrender of Japanese troops stationed there and from October 1945 to February 1946 he served in Tianjin, China. From 1946 to 1951 he served in various posts in the US, and in 1951 he was sent to Korea to serve during the war; after that he returned once again to the US and remained in the USMC service until 1956 reaching the rank of major. From that time on, he moved to Japan where he remained until the year of his death, 1982.

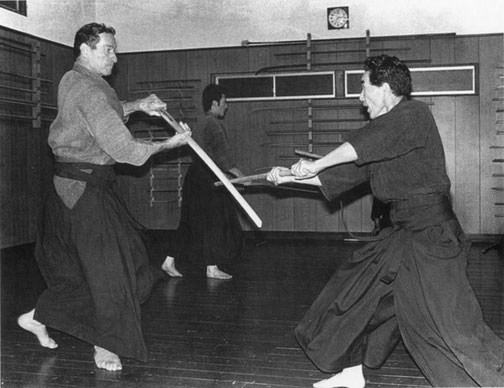

His fourth dan was his passport to the Foreigners Section of the Kodokan where he trained with some of that period’s greats such as Masahiko Kimura, Kyuzo Mifune, Shizuya Sato and Kazuo Ito. Although he was rather low-ranked at the time (at least for Japan’s standards), his interest in judo and his prowess to pretty much anything athletic (by all accounts he seemed to have been a natural athlete since he was a child) made him stand out in the Kodokan rather quickly while his background in weight-lifting back in the US allowed him to become the first systematic weight trainer in judo’s main institution. He trained many then young Japanese judoka but his most famous “success story” was Isao Inokuma: Draeger’s instruction in weights helped him rise from 73 kg to 86 and climb the podium of the 1963 All-Japan Championships, the 1964 Olympics and the 1965 World Championships. As for himself, his aptitude was enough to make him one of the two Westerners who demonstrated judo’s Nage no Kata at the 1961 All-Japan Championships and the first non-Japanese to compete in the All-Japan High-Dan-Holders Judo Tournament.

Training and coaching were not the only areas of judo where Draeger was not only active but actually shone. Even before he came to Japan, he we was among the founders of the US’s first national judo body, the Amateur Judo Association, he helped establish the Judo Black Belt Federation (later, the United States Judo Federation), the Pan-American Judo Federation and various judo clubs in the East Coast of the country and he was trainer at the Pentagon Judo Club. Consequently, after having moved to Japan he became the liaison between the Kodokan and the United States Judo Federation. And, his books on judo (Judo Training Methods with Takahiko Ishikawa, Judo for Young Menwith Tadao Otaki, Weight Training for Championship Judo with Isao Inokuma and the seminal Judo Formal Techniques: A Complete Guide to Kodokan Randori no Kata also with Otaki Tadao) are still considered among the best in the art’s bibliography.

I haven’t managed to establish when his interest broadened from judo to the other martial arts –I have heard accounts that besides being a formidable judoka even in his later years (more than one source confirms that when his earlier training took its toll as is often the case with many energetic judoka, his ne waza groundwork was among the best one could find in the Kodokan –and by then he was in his 50s) he was also a Tomiki Aikido fifth dan while the aforementioned series of books with Shotokan’s Masatoshi Nakayama and his relationship with Kyokushinkai’s Masutatsu Oyama seem to indicate he was well involved with karate as well. I tend to believe that with his background both as a soldier and a martial artist it came naturally and living in Japan and being involved with the martial arts’ world helped it grow and engulf as many aspects of that world as possible.

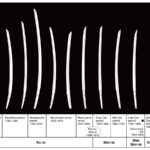

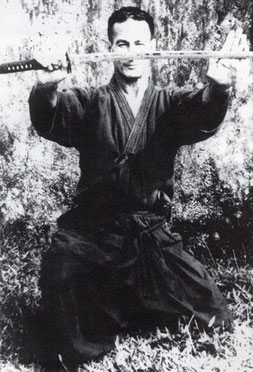

Even those who are unaware of his judo background, know of his involvement with the weapons arts: again, more than one source cites him as a kendo and iaido seventh dan and a very competent practitioner of jukendo even before he entered the world of classical arts through first Shindo Muso Ryu jo (under Takaji Shimizu) and then Tenshin Shoden Katori Shinto Ryu (under Otake Risuke). As with judo, his interest in these arts was deeper than just train (although by all accounts training with him or under him, after he became an instructor –he had a teaching license in both SMR and TSKSR- was among the most intense one could find) so it was natural that after some point he would extend his writing to them. His Martial Arts and Ways of Japan trilogy I mentioned before, the translation of Otake Risuke’s trilogy The Deity and the Sword: Katori Shinto Ryu and Japanese Swordsmanship: Techniques and Practice with Gordon Warner are his best known books related to the armed arts and, like his books on judo are still considered classics.

An account of Draeger wouldn’t be complete without mentioning his broader work in the martial arts of East Asia (i.e. outside Japan), work that included four-month periods of actual fieldwork in various countries for the collection of information regarding the fighting traditions of those countries. Accompanied by a group of dedicated collaborators and students like Phil Relnick, Hunter Armstrong, Larry Bieri, Liam Keeley, Howard Alexander, Quintin Chambers and Meik Skoss, Draeger managed to persuade people from villages of China, Indonesia, Malaysia, Hawaii and elsewhere to show him arts that until then hadn’t even been documented by the practitioners themselves (let alone the rest of the world); a sample of that fieldwork and of Draeger’s academic study is documented in several of his books as well as inComprehensive Asian Fighting Arts which he co-wrote with Robert Smith.

Herein lies Draeger’s legacy: this work saved in his notes was to become the “seed capital” for the creation of a new academic field; Draeger considered that man’s fighting behavior and its relationship to the evolution of civilization was underrepresented in the world of academia, only partially surfacing in anthropology or history. He believed that because people used to fight since the dawn of time, a specialized field studying this behavior should be created and his work, at least for the last ten years of his life was focused on exactly this. It is a sad fact that he died of liver cancer six months after his 60th birthday on October 20, 1982, for many still in his prime and before he had time to establish his study (for which he used the word “hoplology”, from the Greek word “hoplo” or “όπλο”, meaning “weapon”, a term also used by Sir Richard Francis Burton, the 19th century explorer, geographer and writer who first organized this body of knowledge) as a formal science; this task has been left to his collaborators who formed the International Hoplology Society, which, interestingly enough started within the Nihon Kobudo Shinkokai as its International Research Section (Draeger was the first foreigner to become a member of the Nihon Kobudo Shinkokai).

The above makes Draeger’s influence on the world of martial arts hard to describe without resorting to banalities like “enormous” or “immeasurable”. People who have met him, people who themselves came to become some of the world’s most renowned authorities in the martial arts have told me in personal communications for this article that “he was the one who defined the martial arts in a way that made sense to non-Japanese”, that “he was one of the very few people –in Japan or anywhere- who really understood the core of the martial arts” that “he was the best exponent in XYZ art of his time” (and XYZ was any art mentioned in that context) that “he was the first contact any non-Japanese made when they came to Japan wanting to practice martial arts” (his house in Ichigaya –he later moved to Narita- was a landing spot for most of the people who came to study martial arts in Japan until the mid-1960s), that “he changed their lives forever –as martial artists and as people” or that “he was the only non-Japanese that the Japanese called ‘sensei’ –and meant it”.

What I consider the best summary comes from one of my teachers (himself one of the world’s most prominent authorities in the Japanese classical arts) who although not among his closest friends knew him when he lived in Japan back in the 1970s: he wrote “if you trained in any discipline with Draeger, you trained as if your life depended upon it, not out of terror (although he could offer that), but due to his example. You would be shamed to offer any less –because he never did”. I ask you, dear reader, what do you think the influence of such a man must have been?

This article wouldn’t have been possible without the invaluable help of Ellis Amdur, Phil Relnick, Pascal Krieger, Jon Bluming, Seiko Mabuchi, Liam Keeley, David Lynch and Charles E. Eather. I wish to thank the personally for the time they devoted and for what they shared about their teacher, colleague and friend.

A Donn Draeger Bibliography

Solo Authorship

- Weapons and Fighting Arts of the Indonesian Archipelago (Rutland and Tokyo: Charles E. Tuttle, 1972, 1992)

- The Martial Arts and Ways of Japan, Volume I: Classical Bujutsu (New York and Tokyo: Weatherhill, 1973, 1996)

- The Martial Arts and Ways of Japan: Volume II: Classical Budo (New York and Tokyo: Weatherhill, 1973, 1996)

- The Martial Arts and Ways of Japan: Volume III: Modern Bujutsu and Budo (New York and Tokyo: Weatherhill, 1974, 1996)

- Ninjutsu: The Art of Invisibility, Japan’s Feudal Age Espionage Methods (Tokyo: Lotus Press Ltd., 1977; Phoenix Books, 1994)

Co-author

- —– and Ishikawa Takahiko. Judo Training Methods (Rutland and Tokyo: Charles E. Tuttle, 1962, 1999)

- —– and Nakayama Masatoshi. Practical Karate: A Guide to Everyman’s Self-defense (Rutland and Tokyo: Charles E. Tuttle, 1963, 1998)

- —– and Nakayama Masatoshi. Practical Karate: Against the Unarmed Assailant (Rutland and Tokyo: Charles E. Tuttle, 1963, 1998)

- —– and Otaki Tadao. Judo for Young Men, Basic and Intermediate: An Interscholastic and Intercollegiate Standard (Tokyo and New York: Kodansha International, 1964)

- —– and Nakayama Masatoshi. Practical Karate: Against Multiple Unarmed Assailants (Rutland and Tokyo: 1964, 1998)

- —– and Nakayama Masatoshi. Practical Karate: Against Armed Assailants (Rutland and Tokyo: Charles E. Tuttle, 1964, 1998)

- —– and Nakayama Masatoshi. Practical Karate: For Women (Rutland and Tokyo: Charles E. Tuttle, 1965, 1998)

- —– and Ken Tremayne. The Joke’s on Judo (Rutland and Tokyo: Charles E. Tuttle, 1965)

- —– and Nakayama Masatoshi. Practical Karate: Special Situations (Rutland and Tokyo: Charles E. Tuttle, 1966, 1998)

- —– and Inokuma Isao. Weight Training for Championship Judo (New York and Tokyo: Kodansha International, 1966)

- —– and Robert W. Smith. Asian Fighting Arts (Tokyo and New York: Kodansha International, 1969; re-titled Comprehensive Asian Fighting Arts upon republication in 1980)

- —– Howard Alexander, and Quintin Chambers. Pentjak-Silat: The Indonesian Fighting Art (Tokyo and New York: Kodansha International, 1970)

- —– Tjoa Khek Kiong, and Quintin Chambers. Shantung Black Tiger: A Shaolin Fighting Art of North China (New York: Weatherhill, 1976, 1997)

- —– and Leong Cheong Cheng. Phoenix-Eye Fist: A Shaolin Fighting Art of South China (New York and Tokyo: Weatherhill, 1977, 1997)

- —– and Quintin Chambers. Javanese Silat: The Fighting Art of Perisai Diri (Tokyo and New York: Kodansha International, 1978)

- —– and P’ng Chye Khim. Shaolin, An Introduction to Lohan Fighting Techniques (Rutland and Tokyo: Charles E. Tuttle, 1979, 1991)

- —– and Otaki Tadao. Judo Formal Techniques: A Complete Guide to Kodokan Randori no Kata (Rutland and Tokyo: Charles E. Tuttle, 1982, 1991)

- —– and Gordon Warner. Japanese Swordsmanship: Techniques and Practice (New York: Weatherhill, 1982)

Translator

- Otake Risuke. The Deity and the Sword: Katori Shinto Ryu, Volume I (Tokyo: Minato Research and Publishing Co., 1977)

- Otake Risuke. The Deity and the Sword: Katori Shinto Ryu, Volume II (Tokyo: Minato Research and Publishing Co., 1977)

- Otake Risuke. The Deity and the Sword: Katori Shinto Ryu, Volume III (Tokyo: Minato Research and Publishing Co., 1977)

Related article:The Life & Legacy of Donn F. Draeger: An afternoon to remember

About the author

About the author

Grigoris Miliaresis has been practicing Japanese martial arts since 1986. He has dan grades in judo, aikido and iaido and has translated in Greek over 30 martial arts’ books including Jigoro Kano’s “Kodokan Judo”, Yagyu Munenori’s “The Life-Giving Sword”, Miyamoto Musashi’s “Book of Five Rings”, Takuan Shoho’s “The Unfettered Mind” and Donn Draeger’s “Martial Arts and Ways of Japan” trilogy. Since 2007 his practice has been exclusively in classic schools: Tenshin Buko-ryu Heiho under Ellis Amdur in Greece and Kent Sorensen in Japan and, since 2016, Ono-ha Itto-ryu under 17th headmaster Sasamori Takemi and 18th headmaster Yabuki Yuji.

http://about.me/grigorismiliaresis