Text and Photo by Grigoris A.Miliaresis

I love the Meiji Jingu. I love the place itself, a magnificent park offering calmness and serenity right on the border of two of Tokyo’s busiest areas, I love its history ?the relationship with the Ii family and the fondness Emperor Meiji and Empress Shoken had for the place (and especially for its famous and beautiful iris garden)- and I love its nature ?the 100,000 trees of tens of different species and the different kinds of scenery ranging from forests to manicured lawns to unmistakably Japanese gardens. But most of all, I love its symbolism: one of Tokyo’s most famed and most central shrines is dedicated to the man who changed Japan and is located next to an area famous for its youth culture, itself one of the most prominent agents of change; probably the Emperor himself might not completely agree with the dress and behavioral codes of some of Harajuku’s more creative habitues but judging from his penchant for change I doubt he would disapprove of the motives guiding their actions.

Therefore, it seems quite fitting that the Jingu would be chosen as the venue for one of Tokyo’s two major koryu budo demonstrations (the other being, of course, my adopted home town Asakusa), the one held every year on November 3rd, the day Japan honors and celebrates its culture (and in a more subtle way, the birthday of Emperor Meiji); identifying culture with the particular monarch is also interesting since, if the main characteristic of this most important among Japan’s important historical figures was change, it stands to reason that culture equals change. And if kobudo is featured as one of the main events for this celebration it follows that change is also inextricably woven in its fibers.

This might come as a surprise to many ?kobudo is tradition and tradition means “preservation”, right? Wrong! Tradition means “continuance” and there is no other language in which this is illustrated in a more explicit way than Japanese: almost all schools use in their name the word “ryu” (流) and even a very inadequate speaker of the language like this writer knows that the word means “flow”, that is “change”; Heraclitus, a wise man from my neck of the woods, a contemporary of Sakyamuni Buddha, Confucius and Lao Tse said that you can’t cross the same river twice and it’s interesting that all these great Asian philosophers used, like Heraclitus, the river metaphor to express this only constant in life.

If you know where to look for it, change isn’t just in the name of old budo schools ?it’s everywhere! Even in its most fundamental concepts like the “do” one easily discovers the idea of constant movement and endless transformation while the idea of “keiko shokon”/ 稽古照今, of “reflection upon the past to illuminate the present” (to take one random example) from where the noun for our training itself, “keiko” or “practice” comes illustrates in no uncertain terms that change will come and should come and we must welcome it; that this phrase comes from the “Kojiki”, this most ancient and revered of all Japanese texts, means that the old Japanese knew the value of change and stressed its importance. The only thing we need to do is to facilitate it by informing our choices from the past ?this is real, living tradition and I should know: the land I was born in created one of the oldest cultures on this planet!

We don’t need to go into such lofty ideals either: the clothes we wear, the weapons we use to practice, the spaces we practice in are products of change. Most of us don’t train in armor anymore and those who do, use armor made with materials that weren’t available even a few decades back while the rest of us who train wearing cotton keikogi and hakama seldom realize that this precious plant came to Japan during the Sengoku Jidai, the Warring States period of the 15th-17th centuries and that it became common wear for budo only after the Meiji era. And do I really need to remind to knowledgeable readers like those of this magazine that the very arts themselves were, until two centuries ago, the privilege of the few people belonging to the samurai class? How is this for change?

As always, my colleagues at “Hiden” wanted to exploit my advantage as a Westerner ?this time by talking with foreign viewers of the demonstration and by “taking their pulse” so to speak; in other words by trying to figure out what was it that brought them to the Jingu this day and what was it that made them stand for almost five hours watching hundreds of exponents of these very old schools taking turns in presenting what is worth keeping in their respective traditions. And I did and what came out as a common theme was respect for the Japanese and awe in their ability to change these schools and, thus, keep what is most important in each of them alive ?except one or two very misguided individuals who were under the absurd impression that these arts are today exactly as they were three or four centuries ago, most were pretty aware of the fact that what they were watching was the product of years of evolution.

My first conversation was with a retired coast guard officer from Alaska who had lived in Japan for various periods of time (perhaps he was stationed here) and who, although a big fan of yabusame, was a first time visitor of a kobudo enbu. Being a veteran of an armed force, he could very well understand the discipline involved in training in these arts (at that time, the practitioners of Hozoin Ryu were using the two fields to warm up since the actual event hadn’t started yet) and he was quick to notice that even though these traditions were old and that special care was taken to transmit them as faithfully as possible there must have been changes between what we were seeing and what was actually happening in the days of Hozoin Kakuzenbo Hoin Inei (宝蔵院 覚禅房 胤栄). If anything, the monks of Kofukuji didn’t ride trains so they didn’t need to put screws in their enormous spears so they can split them and be able to carry them round!

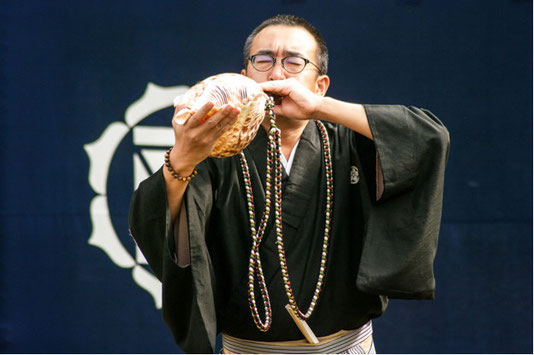

The enbu started with something I hadn’t seen before: the Takeda Ryu demonstrating jingai jutsu or the art of blowing a conch shell on which a mouthpiece is attached. I knew that the big conches called “horagai” had been used by the Japanese military in the same way trumpets had been used by Western armies (i.e. to give signals) but truth be told, in the time I’ve spent in Japan so far, I’d only seen them used for religious purposes and mostly by yamabushi mountain ascetics ?this was the first time I saw them used in a budo context and it was rather impressive. Incidentally, a British couple standing a little behind me thought so too although they believed that it would be more impressive if the exponents were dressed in armor: this was their first time in Tokyo and in a kobudo enbu and, because this is how this event is usually presented in the media, they were under the mistaken impression that all kobudo practitioners demonstrate in armor.

The Takeda Ryu gave their place to Ono-ha Itto Ryu in the first area and to the Shinto Muso Ryu group of Matsui Kenji sensei in the second and I started moving around so I could speak with more people from the crowd. My attention was quickly caught by a burly American (actually, Canadian as I would soon find out) who was taking pictures frantically and had also set a video camera in place; as I soon found out he is also practicing Shinto Muso Ryu in the US and he is a frequent visitor in Japan. Since he had some wrist injury (not budo-related) he couldn’t train so he tried to absorb as much budo as possible through observance. This was not his first Meiji Jingu enbu and we discussed a how interesting it was to notice the differences between various Shinto Muso Ryu groups which introduced again the motif of change even within the premises of a single school.

Personally I was more interested in watching the kodachi kata of the Ono-ha Itto Ryu so I returned to my spot for some pictures; there were very specific things I wanted to watch in this enbu but this set proved to be an unexpected bonus and got me thinking once more about how seen different aspects of a school differentiates your understanding of it ?this time the concept of change came from the observer’s side (i.e. mine) and I’m pretty sure that I was not the only one who came to this realization. And surely enough, a couple of hours later, I found out that my observation was shared by two French karateka who were there to watch the Okinawan kobudoka but who also enjoyed the weapon arts; these guys also travel frequently to Japan (they even spoke some Japanese) and if I’m not mistaken, they had timed this visit to coincide with the Meiji Jingu enbu.

By the way, the schools I wanted to see were the jujutsu school Ishiguro Ryu from Chiba dating from the Bakumatsu era, the kenjutsu school Taisha Ryu from Kumamoto dating from the mid- 16th century and the kenjutsu school Maniwa Nen Ryu, perhaps one of the earliest extant schools, dating from the mid-14th: the first two I had only heard of and/or seen in video and the last I had missed in the Meiji Jingu two years ago when they demonstrated at the exact same time I was demonstrating at the next area with the naginatajutsu school Toda-ha Buko Ryu! Needless to say I was impressed by their strong kenjutsu and their unique use of kiai which, from what I have read is an important part of their training. The only aspect of their art that I didn’t get to see was their free-practice performed with fukuro shinai and protective equipment much earlier than that of kendo. I did find very interesting some of their more advanced kata though (also performed with fukuro shinai and a single kote), as well as their naginata which I found in some ways remarkably similar to that of our Buko Ryu.

Speaking of naginata, it was wonderful seeing again the Chokugen Ryu and their use of the big naginata the one close to what we call a “nagamaki” in Buko Ryu; especially fascinating was seeing a female practitioner wielding it since this is obviously an old school weapon certainly preceding the era the naginata became a women’s choice. Seeing a woman using an undoubtedly “male” weapon which wouldn’t look out of place in the hands of legendary 12th century sohei fighting monk Benkei, made me once again think about, yes you guessed it, change: this spectacle would have been impossible a couple centuries ago. But come to think of it, the very idea of a 60-odd schools demonstrating openly together is also a product of change, isn’t it? Up until the bakumatsu era, ryuha would find such a notion too nonsensical to even consider it.

The Ishiguro Ryu and the Taisha Ryu, came and went ?I’d certainly love to see more of both since I know that the first one is a sogo school with lots of interesting stuff including sword, shuriken and some small stick resembling (presumably) a drumstick while the second has a relationship to Shinkage Ryu which I’d like to explore. Other schools followed, mostly stuff I’ve seen again and again but always exciting to watch but there was something that really caught my eye ?and the eye of almost all spectators, Japanese and foreign: the two very young children, a little girl (we’d late find out she was four years-old!) from Owarikan Ryu performing one and two swords kenjutsu and a little boy from Kurama Ryu, performing with his father, the soke of the school. Is there, I wonder anything symbolizing the ever-changing stream better than a four or a six-year old training in a centuries-old school?

These were the thoughts buzzing around my head as we walked through the JIngu towards Omotesando. The things I’d seen these past five hours, the conversations I had ?even the very spot I was been in the space-time continuum- all pointed out to the same thing: as much as these extraordinary arts are something of the past, they are something of the present and something of the future and this happened because they didn’t stand still in time ?they evolved. And it couldn’t have been any other way: their very nature is rooted to the idea of conflict and conflict is a rapidly changing chaos ?what chances do you have when facing chaos if you don’t embrace change and consciously flow with it? There is a reason why the deity of immovable wisdom, the fearsome swordsman Fudou Myo O, can almost always be found next to a waterfall, you know…

About the author

About the author

Grigoris Miliaresis has been practicing Japanese martial arts since 1986. He has dan grades in judo, aikido and iaido and has translated in Greek over 30 martial arts’ books including Jigoro Kano’s “Kodokan Judo”, Yagyu Munenori’s “The Life-Giving Sword”, Miyamoto Musashi’s “Book of Five Rings”, Takuan Shoho’s “The Unfettered Mind” and Donn Draeger’s “Martial Arts and Ways of Japan” trilogy. Since 2007 his practice has been exclusively in classic schools: Tenshin Buko-ryu Heiho under Ellis Amdur in Greece and Kent Sorensen in Japan and, since 2016, Ono-ha Itto-ryu under 17th headmaster Sasamori Takemi and 18th headmaster Yabuki Yuji.

http://about.me/grigorismiliaresis